Catherine Vincent

I arrive in front of Hotel Peron where I have an appointment with Vincent. The façade is sublime, white and majestic, facing the sea. I can imagine the sun-covered bed. I hurry upstairs. I want to arrive before him so I can write “I was on the bed; I read, and I was smoking,” as Walter Benjamin writes in his account. We had been promising ourselves this elegant daytime rendezvous in a hotel for a long time, so we may love each other passionately by day, and under the influence of hashish.

I woke up startled in the middle of the night. I didn’t know where I was. Frightened, it took me a moment to find the lamp switch, but even lighting the room did not reveal anything to me. Berlin, Damascus, Marseille? Little by little, the fear of not knowing where I was turned into a sadness in realizing where I am. Too much smoke last night confused me. The evening comes back to me in bits and pieces. Moments, phrases, laughter, tears in my eyes. The walk in the deserted city in search of the restaurant that Walter Benjamin mentioned, Basso, number 5, Quai of the Belgians, where he went to eat alone after smoking hashish. The restaurant no longer exists, and even if it did it would be closed in these times of pandemic and extreme sanitary measures. I had let myself be lulled by the sound of my own footsteps in the empty streets, suddenly frightened by the sight of a police car… We’re defying curfew to find accomplices if we can’t hang out in bars.

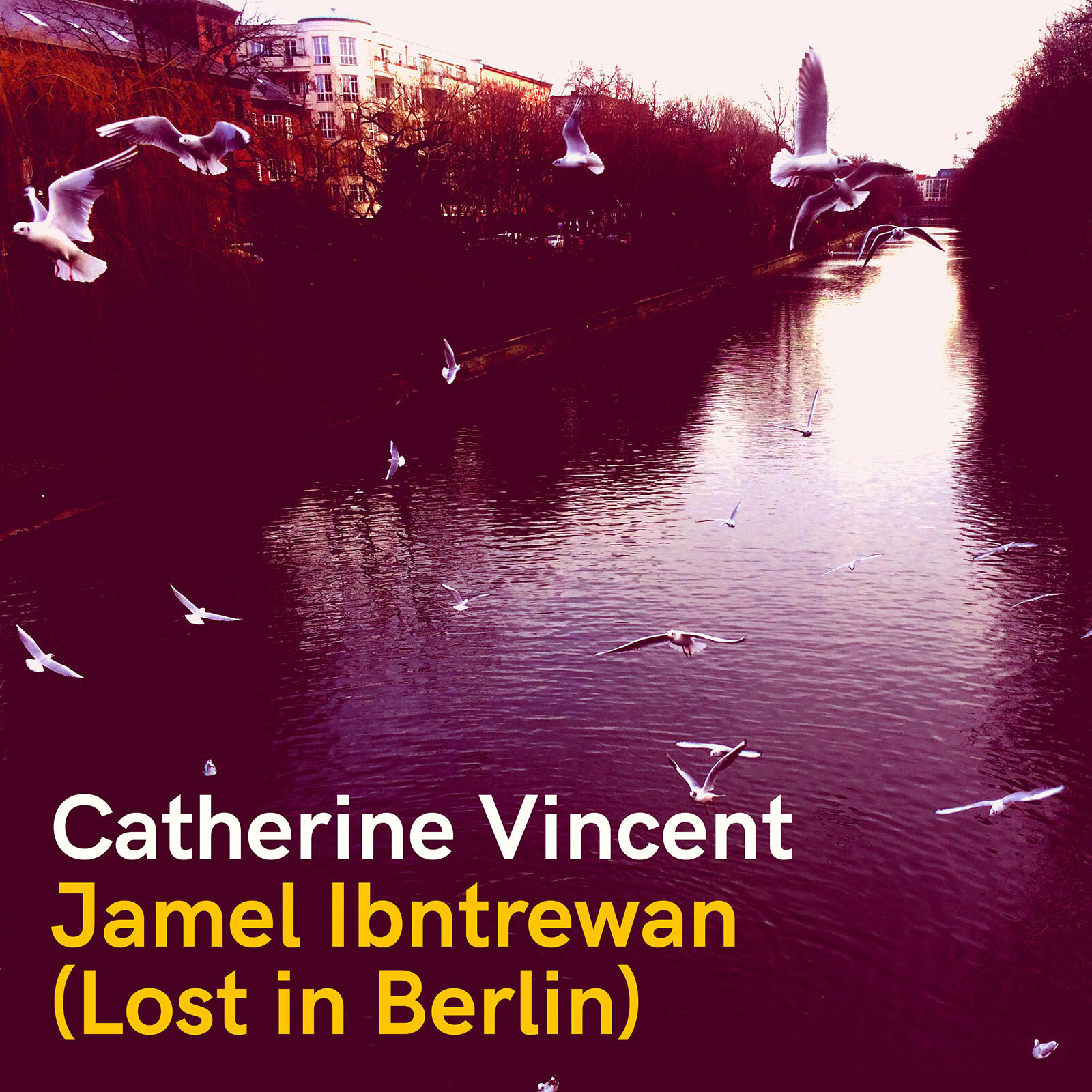

In Berlin, where Vincent and I spent a month last year, we also listened to our footsteps. I wore heeled boots, which hit the pavement smartly, making it resonate. We walked at night through the dimly-lit streets of Kreuzberg. Vincent showed me how to hold the recorder, how to orient it as I recorded my steps. We were happy with this sonic find that would later evoke our stroll. We used this sound to pace our conversations about our character in the making, Jamel Ibntrewan (an anagram of Walter Benjamin).

He’s the one we are searching for in Berlin, this Syrian intellectual who had dedicated himself to the Revolution that shook his country in March 2011, and who was forced to flee the regime’s repression against him and all those who dared raise their voices against power. He took refuge in Berlin where he was granted asylum. It is Jamal Ibntrewan who named our album “Jamel Ibntrewan (Lost in Berlin).”

So we moved away from Mediterranean sweetness, its blue sky and bright light, and dived into the German capital with its short days and pale glow. We were certain that it was in this city that we would find Jamel Ibntrewan. Walter Benjamin had to flee Berlin, because he was Jewish and opposed to Nazism, and today it is home to thousands of Syrian refugees. Since 2015, we have been impressed every time by the large presence of Syrians in Berlin’s neighborhoods, from Schonberg and Neukiln to Grunewald. In January 2020, we hung out mostly in Sonnenalle, “Street of the Arabs.” Everything reminded us of Damascus: the people, pastries, chicha bars, jewelry stores, and restaurants of course, where all of a sudden we felt less foreign because we could order in Arabic — we who do not speak German.

In crossing Tiergarten that marked Walter Benjamin’s childhood, we find, on one side of the park, the building that houses the archives on the second floor of a very austere grey building. On the wall of a corridor hangs a large map of Berlin: the black dots indicate all the places in the city where Benjamin lived, and the white dots show the public places he frequented. On the other side of the park lies the Philharmonic which offers free concerts every Tuesday at 1 pm. The hall is regularly filled with a heterogeneous crowd, relaxed but also very attentive in anticipation of a concert that lasts a little less than an hour. We loved the atmosphere of this weekly event, the sober décor, the hushed light of this vast building.

Jamel lives in Berlin, disoriented in his exile, lost in his painful memories, and he wonders how this city that suffered so much during the war could provide him with a sense of protection he needed. And this welcoming home, the Philharmonic, is one of his favorite places of refuge. The old Opera House was destroyed by bombing in 1944. By this time Walter Benjamin had already left the city. He’d even been dead for four years. Today the Damascus Opera House, named after the Syrian dictator, is still standing in Umayyad Square. If the Syrian capital is almost intact, from its suburbs and outwards through the entire country is nothing but ruin. Bashar al-Assad and his allies bombed wherever the wind of revolt was blowing.

I don’t think Walter Benjamin attended the Marseille Opera House, but he certainly passed nearby because he stayed downtown, just 300 meters from the avenue La Canebière. I live in Marseille, and since I have had Walter Benjamin in mind, I wonder all the time: did he come here? Did he walk these streets? Did he stop in the middle of the Christmas market at Café Prinder where the date 1925 still reads above the counter? We know that he did not limit himself to downtown, that he went as far as the Saint Louis district, rue de Lyon, Boulevard de la Jamaïque in the 16th (of the quartiers nord) where, as he wrote, “the decisive battle between city and country,” between agaves and lampposts, building towers and plane trees, still rages on.

Night is falling. On the horizon, the hills of the blue coast on the other side of the harbor of Marseille remind me of Damascus. I know it has nothing to do with Damascus—only the urge to think of it. And yet it is I find myself still suspended in memories of Berlin. That memorable evening with R and F, two Syrian friends, spent in shisha bars. We had been there with F for some time and I was observing. There were only Arab men, all dressed similarly, wearing tailored garments to highlight their very muscular bodies, sleeked-back hair, well-cut beards. When R, who lives in Berlin, joined us, I asked him the question in Arabic. How is it that there is not a flag of the revolution, a poster, something to indicate the political color of this café? And his answer came in a voice even more hushed than I used to ask my question: they are all pro-Hezbollah here! Frightened, the three of us took a leap backwards and our reaction made us burst out laughing!

Berlin, city of exiles; Marseille, city of emigrants. Are these emigrants the exiles of yesterday? In 1940 Walter Benjamin had come to Marseille for the last time. He who had loved to visit was this time only passing through. The city was teeming with foreigners fleeing Europe, who were waiting for the many permits needed to leave. Having not obtained the exit visa from France, he crossed the border clandestinely to Spain. Arrested by the police in Portbou he chose to commit suicide so as not to be handed over to the Gestapo.

Vincent chose the Moroccan room. He wanted for us to stay for the night as well. The mistral blows hard today making the light rawer and more beautiful than usual, but it will be difficult to keep the windows open to avoid smoking-up the room. I prepared a joint in advance. I’m slipping off my shoes. I’m lying down. I light it. I’m holding my book. I’m on the bed as I read and I smoke.

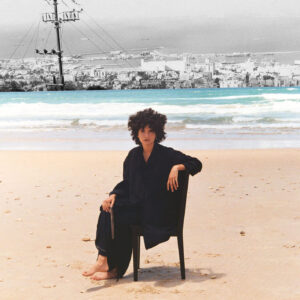

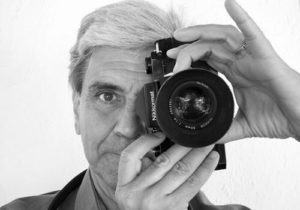

This essay is written with four hands by Catherine Vincent, a folksong duo based in Marseille, with Catherine Estrade and Vincent Commaret. Their duo was born in Damascus, Syria, where they lived in the early 2000s.

Click to listen…

In January 2021, their latest album Jamel Ibntrewan (Lost in Berlin) was released, a musical and sound ride that takes us from Berlin to Damascus via Marseille and Portbou, following in the footsteps of a Syrian exile, Jamel Ibntrewan, dedicated to the revolution that shook his country in 2011. His destiny mirrors that of the German thinker Walter Benjamin.

Recommended Reading

Books by Walter Benjamin:

A Berlin Childhood Around 1900

On Hashish

Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings

About him:

On Walter Benjamin’s Legacy in the Los Angeles Review of Books

La vie de Walter Benjamin wbenjamin.org