Many are convinced that freedom of speech has limits, that it should exclude hate speech, or insults, or derogatory comments, or offensive opinions, especially those related to religion. But if it did, why would free speech even need protection?

“If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear.”

—George Orwell

Joumana Haddad

Tabbouleh is a traditional Lebanese salad made with bulgur, parsley, mint and chopped vegetables, seasoned with olive oil and lemon juice. It is extremely popular and beloved in Lebanon, to the extent that it has become a source of collective pride and a national symbol, just like our famous cedars. Once, some ten years ago, three hundred people gathered in Beirut and broke a Guinness world record by preparing the largest bowl of tabbouleh ever made. People still brag about it to this day. That’s how iconic tabbouleh is in our country.

Now imagine that I do not like tabbouleh, however exquisite it may be to the majority. And let’s suppose that one day, I express my dislike and criticism of tabbouleh outspokenly, on some platform of mine, whether virtual or in the real world. I might even throw in a joke, saying that it comes a close second in uniting Lebanese people after the national faculty of denial. In principle, this is my own taste, my own point of view, my own — however cynical — sense of humor, and I should be free to express it. Right?… Wrong! You see, there are tabbouleh fanatics out there. They LOVE tabbouleh and are very sensitive about anything related to it. They read or hear my criticism somehow, somewhere (I wasn’t even addressing them when I stated it; I was just venting in my own space and they happened to stumble upon it) and they feel deeply hurt (you might say “triggered,” a word very much à la mode nowadays). So, they launch a witch-hunt against me. Their trolls stalk me everywhere and try to destroy my morale, my reputation, my work, etc. They demand that I apologize, ask for forgiveness, be “cancelled.” For how dare I denigrate something they feel so strongly about? How dare I disregard their feelings and talk about tabbouleh the way I did? I might argue that I criticized the product, not its devotees; I could add that I didn’t call for the lynching or killing of those who love/revere the product; that, after all, I am entitled to my personal opinion, and that they can simply criticize this opinion of mine, or ridicule it, or ignore it, or unfollow me, or block me. But that wouldn’t be enough for them, would it? Their right to free speech (slander and harassment, more often than not) is far more important than mine. Moreover, their personal sensitivities and intellectual/religious/political etc (in this case dietary) comfort are way more precious and valid than my views, so I must completely disappear. Then and only then, justice would be served.

The scenario above might seem quite absurd, exaggeratedly Orwellian even, but I’ve intended this vulgarization to sound an alarm about the dangerous direction in which we are heading, slowly but surely. And I’m not just talking about Lebanon or the Arab world. This is happening everywhere, on a daily basis, and is scary and distressing to say the least. Social media platforms like X have become a hotbed of toxicity, negativity and calls for censorship. Now you might say that I’m belittling the existing polemics, some of which are crucial, by making an analogy between significant causes and something as trivial as a salad, but I am not. For this is how every descent into totalitarian darkness begins. It is a slippery slope. And those who feel strongly about trivial things can easily be drawn into considering them as important as, let’s say, an issue as controversial and sensitive as religion.

Let me be clear here on one point: To me, religion and tabbouleh are of equal importance, or should I say, unimportance, but I chose religion because it has always sparked widespread controversy about whether we can, or cannot, criticize it, or belittle it, or make fun of it and its symbols and figures (we definitely can, by the way, and should be able to), as if it deserved some kind of special treatment. Who says something like tabbouleh won’t be put on the same level somewhere down the road? Fanatics are fanatics, and they tend to emulate each other. Right wing Islamophobes and Islamic fundamentalists in the West are but two among many examples of this dangerous trend.

Let me also be clear on a second point, before the guns are loaded: By no means am I aiming to defend the racists and homophobes and misogynists of this world, and their nasty likes. However, in my humble opinion, these have always existed, and they always will. We might hear their voices more loudly now because of social media and the open world of the internet. Unfortunately, the right to free speech encompasses the pricks and imbeciles as much as it does the decent and kind, and cancelling the pricks and imbeciles won’t make them disappear. Quite the opposite: they feed on what they perceive, or pretend to perceive, as “prejudice” against them, and gain more fame, and even more endorsement and leverage in some cases (which is why they might have launched their provocations in the first place, in a world where even bad publicity is good publicity). It’s a series of useless, energy-consuming vocal wars between what will forever remain a relative right and a relative wrong, depending on which side you stand, while pressing problems like poverty, famine, human trafficking, genocides, etc remain largely untackled.

I’m not pretending that there aren’t topics I feel very strongly about. They are many, and I am invested in each and every one of them. On top of my list are, obviously, women’s rights and the issue of inequality. But I have long stopped wasting my time debating with sexists and giving them the time of day. They are simply not worth it, and such an exchange won’t lead to any transformation in their behavior or way of thought (I once was idealistic or naïve enough to think it would), not to mention that I’d be granting them the attention that they crave. I’ve learned that there are better, more efficient ways to shed light on these issues, fight for them, and maybe, just maybe, make this world a better, more dignified place for the oppressed. I’m not trying to encourage indifference and deter watchfulness or debate here, I’m only saying that many of said ongoing debates, especially on social media platforms, are mere distractions.

Because there’s a crucial distinction to be made between, for example, declaring that women are less important than men and that they’re only good for cooking and making babies and declaring that women “deserve to be beaten up.” The first is an expression of bigotry and idiocy (undeserving of a response or reaction per my current standards), and the second is an incitement to violence, which should be punished by law. It’s one thing to make jokes about homosexuals, and another to advocate that they “should be killed.” Many people are convinced that the line between expression of hatred or bias (free speech, however disgusting) and calls for violence is a blurry one, but it’s actually quite clear.

Furthermore, I’m not saying you can’t or shouldn’t take active action against people who spread hate speech. I’m merely saying that censoring them is not the most efficient punishment. You are merely covering up the dirt, not actually cleaning it. And since when did sweeping the dust under a rug make the dust disappear?

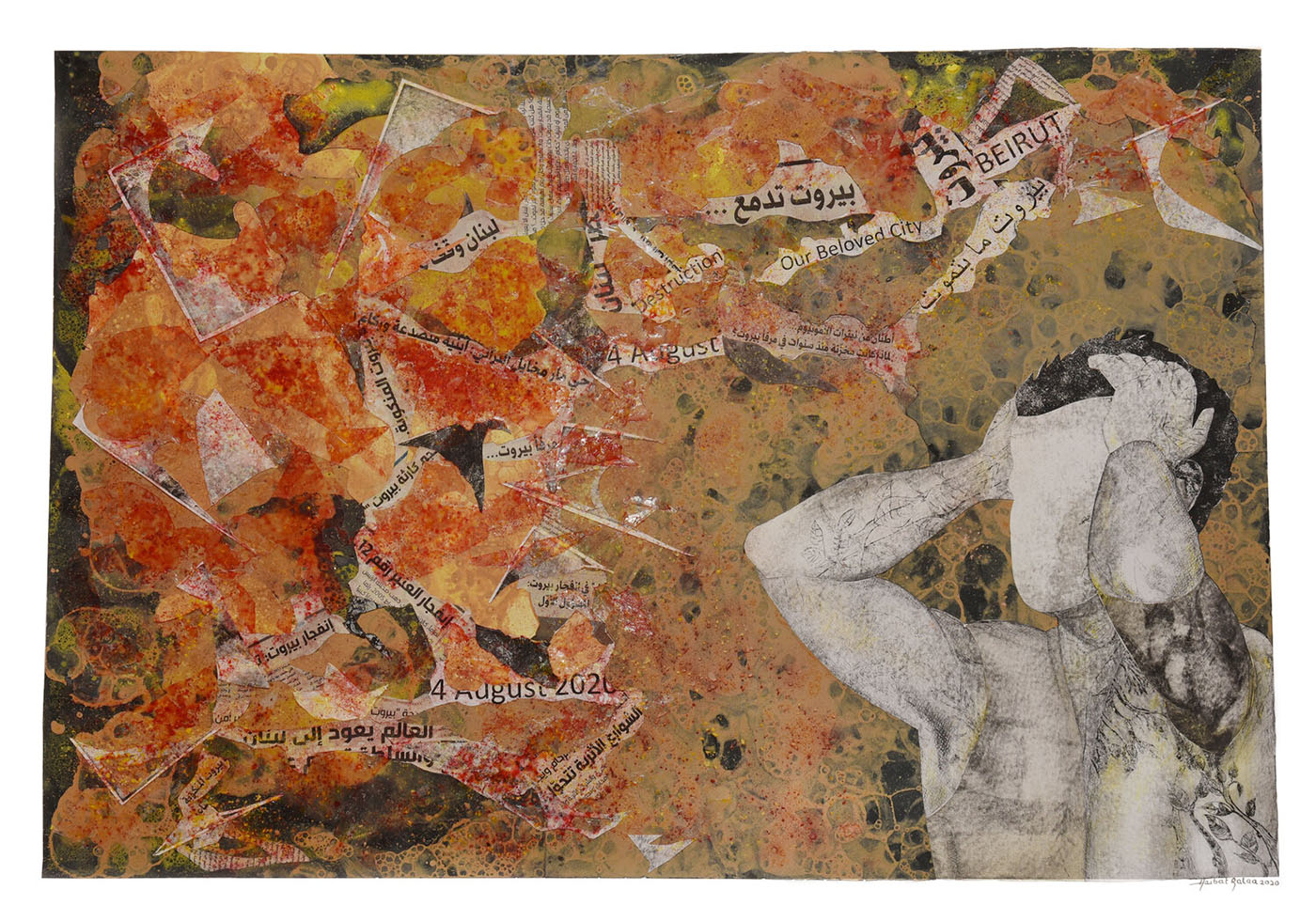

The reason for this rant is an ongoing — and increasing — concern for the state of freedom of speech in Lebanon today. Obviously, there have always been things you cannot think in our dear country, let alone say, or do. This is the world I grew up in, and this is the world I am still living in right now, unfortunately. Religious leaders and institutions in particular have long been the gatekeepers in Lebanon. Only a few months ago, Lebanese stand-up comedian Shaden Faqih was accused of blasphemy because of some jokes she made about Islam on stage. The death threats she received were so serious she was forced to take the decision to leave the country for good. Faqih is, by the way, from a Muslim background — it doesn’t matter to me, of course, but it does matter to the story. She was accused of “inciting religious and sectarian conflict and undermining national unity,” according to Dar El Fatwa, Lebanon’s seat of Sunni authority, and also of “threatening civil peace.” One cannot but be amazed by such a level of hypocrisy. This is a country where corrupt political leaders have completely ruined the State, where catastrophic explosions and assassinations have taken place without anyone being charged for the crimes, where banks stole citizen’s deposits, and a whole region, the South, is being bombed by Zionist criminals — among many other calamities brought upon us on a daily basis. Yet a simple joke can seemingly outdo all this and annihilate us. Now if this isn’t the actual joke, I don’t know what is.

Do Muslims have a monopoly on this heightened touchiness? Not in Lebanon. As I mentioned before, zealots love to copy each other, and that is for various reasons: one could be a certain form of social jealousy (“why should their cause be more relevant than ours?”), another is covert mutual interests (“if we provoke them into attacking us, we’ll be more credible victims and our cause will gain more traction and validation”). Lebanese Christians are just as thin-skinned as the rest of our god-fearing population. To cite but one example, a radical Christian group called Jnoud el Rabb (a.k.a. the soldiers of God, as if God doesn’t already have enough armies and parties), has emerged in the past couple of years, waging a religious war against the LGBTQ+ community and the so-called “spreaders of sin.” Only last summer, they attacked a gay-friendly club in Beirut and assaulted its patrons and owners. Shortly before that, the Lebanese interior minister had decreed a ban on any activities related to Pride Month after pressures from different religious groups, Christian and Muslim both. And there have been many other incidents in the past which have showcased the lack of tolerance for free choice and free speech amongst Christian religious leaders. In 2013, a group of Lebanese Orthodox priests protested the use of a popular church hymn in a modern dance show at the Baalbeck Festival, and called for its banning. In 2019, the Maronite Catholic Eparchy of Byblos claimed that Mashrou’ Leila’s songs “violate religious values” and demanded their show at the Byblos festival be canceled, which it eventually was. Church leaders accused the band of blasphemy and many people sent them death threats on social media.

This is one of the best materializations of the famous proverb — especially pertinent in Lebanon — “you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours.” For when fanatic Lebanese Muslims and fanatic Lebanese Christians aren’t fighting one another, they make the best war comrades, waging the same battle against modernity, secularism, open-mindedness and against freedom of expression and choice (specifically any choice related to one’s gender and sexuality), in order to protect — not their convictions, not really — but very much so their interests, their power and their lucrative grip on the Lebanese people, a grip which ultimately serves the corrupt political elite with whom they conspire. And it is about time this country’s religious leaders take their chokeholds off our lives and voices, whether in politics, culture, sexuality, or any other field.

Many are convinced that freedom of speech has limits, that it should exclude hate speech, or insults, or derogatory comments, or offensive opinions, especially those related to religion. But if it did, why would free speech even need protection? Should it just be a conduit for sanctioned beliefs and praise and compliments? Our opinions, whatever they may be, can easily be considered hate speech or an insult or an offense by someone who feels strongly about what we are critiquing or ridiculing. The principle of freedom of speech is specifically meant to protect the speech that someone else might find offensive or mean or wounding or objectionable. Shouldn’t we be able to say anything as long as it doesn’t incite violence or crime? Do human beings have a birthright to not be offended? Being able to hear all kinds of opinions, even — especially — ones you don’t like, even — especially — ones that hurt your feelings or your beliefs, however sacred these beliefs are to you, is an essential part of a free society. We need to remember that “sacred” is both a relative and subjective category. We also need to remember that if someone says something on social media or elsewhere, it doesn’t make their statement true or a “fact.” But herein lies the conundrum: to many, unfortunately, it does indeed make it true. It’s frightening how countless people can be so quick to believe (and relay and spread) something they read on some platform, posted by some anonymous account, even if, especially if, it is saying something negative. This is our real problem: a universal lack of consciousness, lucidity and ability to question and evaluate. Free speech requires societies that are aware, discerning and able to practice the art of critical thinking. That is why human ethics and basic decency and civility are the solution, and promoting them over discrimination, exclusion and aggressiveness can offer a major breakthrough in this otherwise unfruitful and counter-productive debate.

I’ve never been a fan of political correctness. I believe that insolence, irreverence and desacralization are vital to shaking us out of our comfort zones, combatting the cancer of duplicity, and protecting us from brainwashing and indoctrination. We need to constantly fight for our right to diverge, to not fit in, to not be “mainstream,” to not conform with the masses. Last but not least, let’s keep in mind that there is a name for a place where everyone agrees with each other: It is called a dictatorship.

Look around: our Arab world is rife with them.