A joint Arab/Kurdish exhibition at Baghdad’s The Gallery showcased how the nation’s “two solitudes” can unite through art. “In a time when maps are redrawn and memory is rewritten, the true homeland is what lives in the soul and identity remains an unbroken thread — regardless of time or shifting borders.” —The Gallery, Baghdad.

Hadani Ditmars

A recent exhibition at Baghdad’s The Gallery, billed as the first joint Arab/Kurdish exhibition in the capital in two decades, was a study in how the nation’s “two solitudes” can come together through art. Featuring ten artists and 30 works, the stars of Infrangible were Sulaymaniyah-based Osman Ahmed, an artist who has dedicated his life to documenting his people’s genocide, and Fakher Mohammed, an Iraqi artist and prominent member of the Baghdad Modern Art Group, who studied under the mid-century school’s co-founder, Shakir Hassan al Said. (Jewad Selim, who designed the Tahrir Square Monument to Freedom just before he died, initiated the group with his former student al Said.)

Opening on the eve of the Arab League Summit, in a city all spiffed up with fancy new five-star hotels but a still non-functioning electrical grid some 22 years since the invasion, it was a suitable aesthetic response to the “Let’s Make Iraq Great Again” mania gripping Baghdad.

Now, thanks to an improved security situation credited by many to the efforts of Prime Minister Sudani, as well as anti-money laundering laws introduced by the Americans in 2023 that channeled dirty money hitherto destined for Iran and Lebanon into the local economy (including a number of new art galleries), Baghdad appears on the surface to be doing well. Dozens of new construction projects lend a veneer of prosperity to Iraq’s capital, in spite of apparent economic decline as oil prices continue to drop.

And the Arab League summit motif — a circular riff on Caliph Mansour’s round City of Baghdad — evokes the kind of Neo-Abbasid aspirations that informed Saddam Hussein’s ambitious Rifat Chadirji-led architectural additions to the city, in preparation for a Nonaligned Nations meeting in 1981 that never happened due to the war with Iran.

Timed well for the upcoming national elections in November, the summit spurred the construction of three new hotels including a Movenpick, and one that remains under wraps. A third one called The Heart of the World — perhaps a reference back to the Abbasid glory days when Baghdad was just that — housed the “press center” (where there were only two non-Arab journalists, hardly any English translation and a single Chinese blogger who sent his greetings to Sudani from President Xi Jinping in classical Arabic). Here an entranceway flanked by a wannabe pop art version of Cesaire Baldaccini’s giant thumb sculpture La Pouce mixed uneasily with a neo-classical marble lobby decorated with a pastiche of rococo fantasia — Watteau paintings, reimagined in day glo needlepoint.

But before all of this neo-colonial/state capitalist kitsch, there was a serious contemporary art scene in Baghdad, and The Gallery’s latest exhibition bodes well for its return. Sadly, it’s not only Iraq’s ancient sites that have been looted but also its modern heritage. The Saddam Arts Centre, now reimagined as the National Museum of Modern Art, had over 85% of its 20th century art works stolen, after the invasion, with an unknown number of pieces reappearing at prominent Western auction houses.

Maki Omran’s surreal collages of what he names Overlapping Worlds that blend images of extra-terrestrials, ancient sites, American war planes, Donald Trump with a tattered Iraq flag on his arm and grieving Sumeriam goddesses, that reads like an iphone scroll through history and yet somehow manages to capture Iraqi reality.

In many ways, this ambitious exhibition at The Gallery was an exercise in nation building and a reminder of what really makes Iraq great — its depth of culture and history. Amidst all the wheeling-dealing frenzy of corruption, the apocalyptic climate change/fracking induced air quality, and heightened sectarianism, it was a small sanctuary of rohe iraqeeyeh — Iraqi soul.

While current genocides — like the one unfolding in Gaza in livestreamed horror — have been televisualized ad nauseum, the Kurdish genocide was hidden under a veil of secrecy and state repression. Artist Osman Ahmed’s life’s work has been to reclaim agency for its victims by revealing the reality of the genocide through his art.

Ahmed graduated from the Institute of Art in Sulaymaniyah in 1985 and went on to teach art to children in rural Kurdish villages. A survivor of the Anfal campaigns that began in 1988 as a Baathist counter-insurgency campaign at the end of the Iran/Iraq war, he fled to the UK in 1990, escaping first across the Iranian border. While he was in Tehran, he held an exhibition of works inspired by the children of Halabja at the Museum of Contemporary Art, and worked for the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan’s media department. When he went to Syria for six months for an embassy of Kuwait sponsored exhibition about victims of Saddam Hussein, he met Jalal Talabani, who helped him get to Moscow. Ahmed finally obtained asylum in the UK in 1991, taking odd jobs to support himself, and working on his art as he was able.

Ahmed earned his MA in Drawing from Camberwell College of Arts in London, and his PhD from Chelsea College of Arts, University of the Arts, London. His PhD project documented the Kurdish genocide through drawing and recording the testimonies of 15 Anfal survivors as well as investigating the Kurds’ collective memory of the genocide.

In a way, his doctoral project never ended. It has become his life’s work.

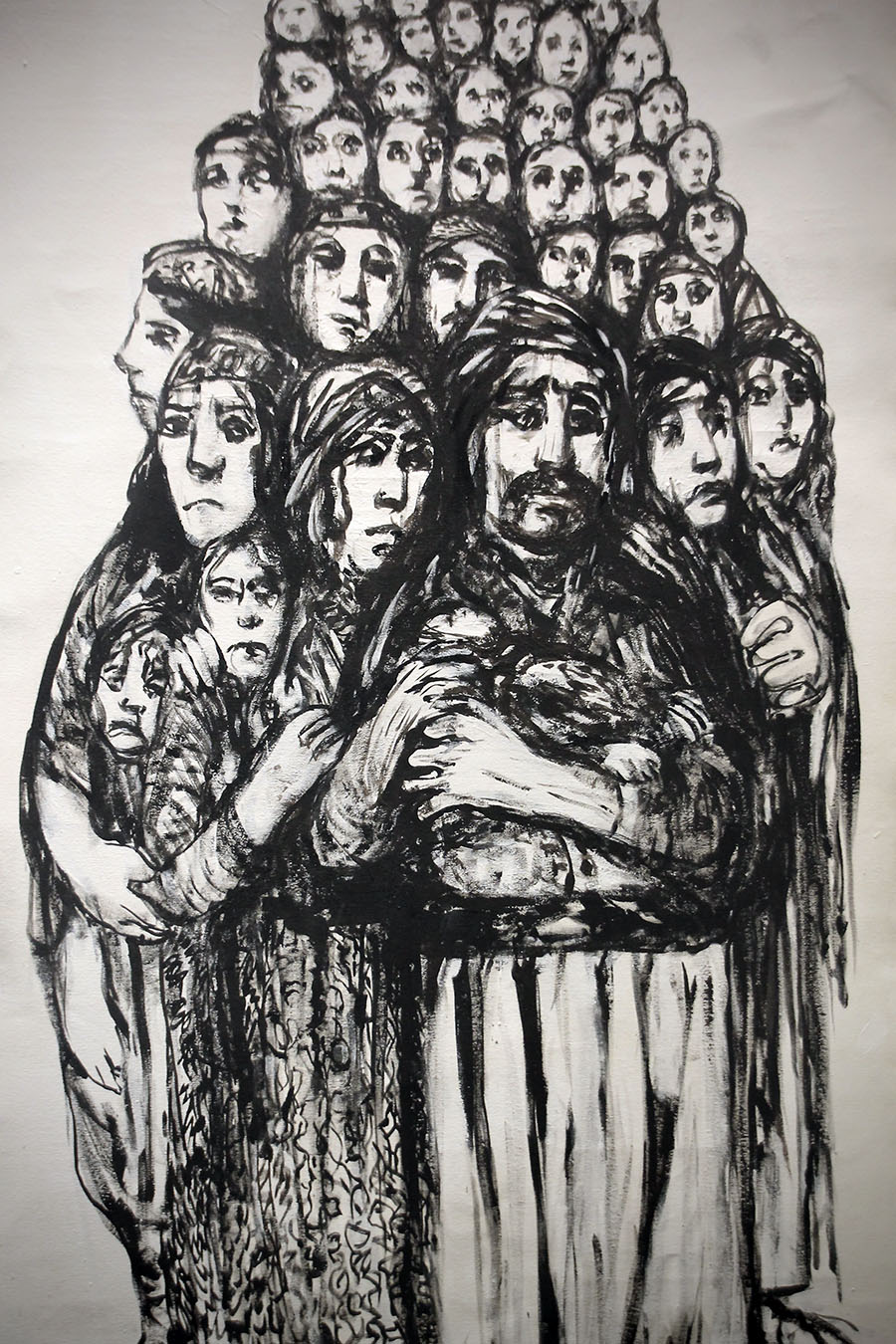

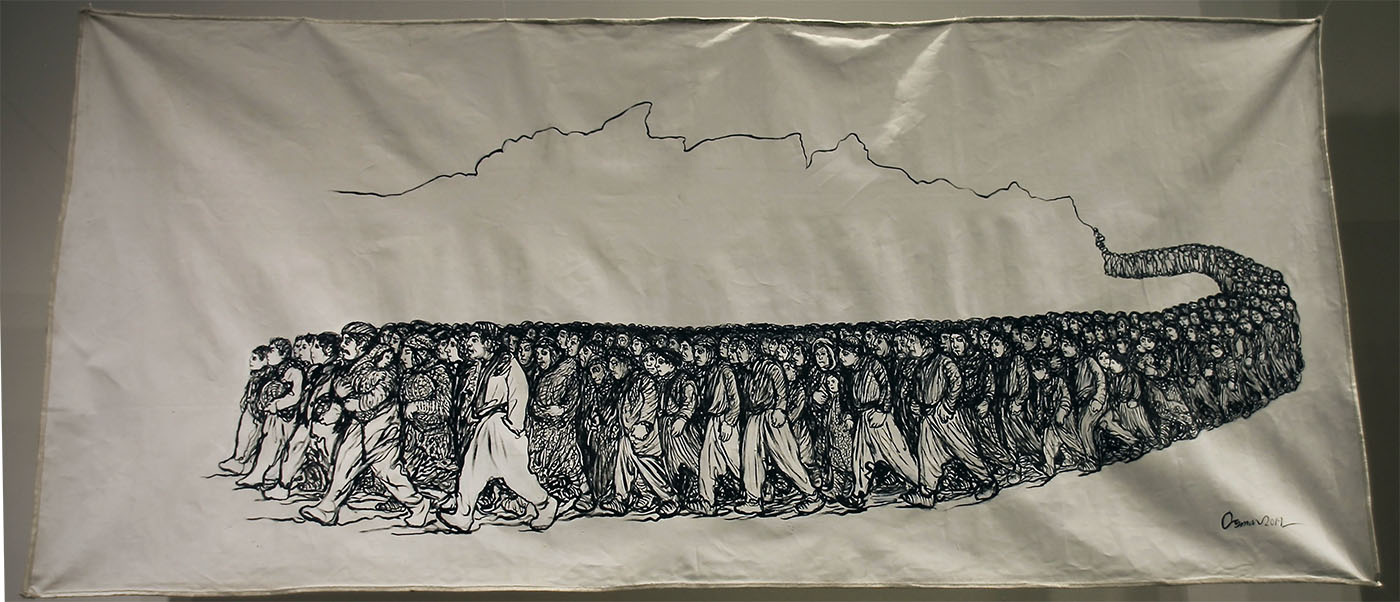

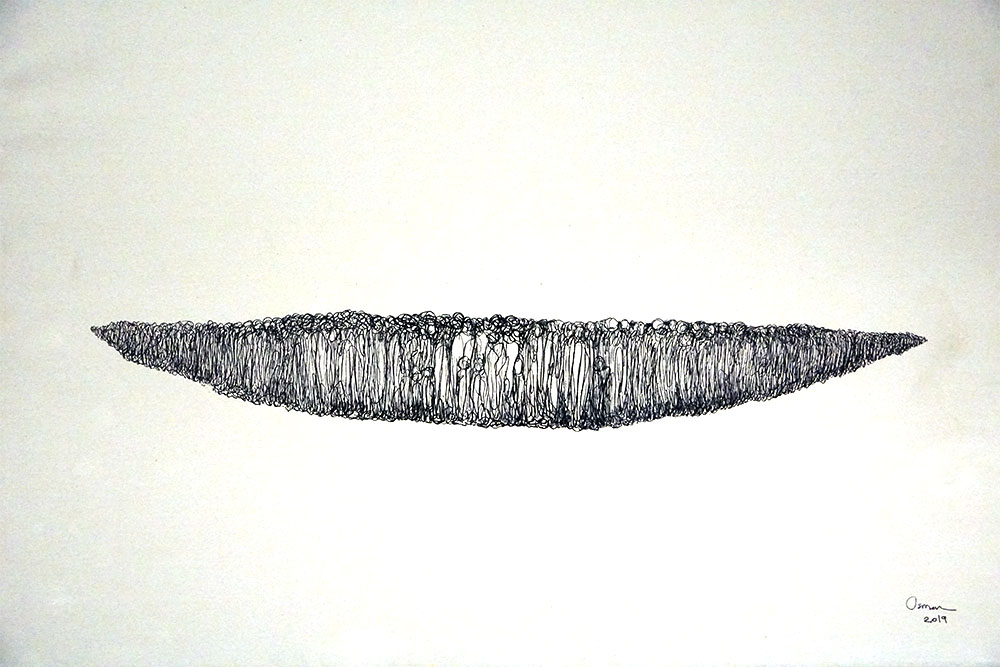

Through delicately detailed pen and ink drawings of scenes from the genocide, he evokes both the pathos and ongoing resistance and solidarity of the Kurdish people. But with a de facto Kurdish state within Iraq now plagued by both its own corrupt leaders and disappearances of opponents, as well as ongoing Arabization campaigns in and around Kirkuk, his work takes on a new poignancy and urgency. He seems a man possessed by the crucible of the Kurdish dream; he just can’t stop drawing scenes from his memory of mass displacement, imprisonment and exile, where crowds of individual victims seem to merge into a single human face.

His four works in the show span from 2019 until 2025 — all shown for the first time in Baghdad. His latest work is an untitled 600x100cm acrylic on canvas vertical drawing, depicting a long line of humanity that slowly unwinds downward across the canvas to reveal individual human faces. Another acrylic on canvas work from 2019 is a 30x130cm horizontal version of a similar play of line and perspective, with a formline suggestion of the mountain homeland of the captive Kurds. A pen and ink drawing from 2019, compresses a mass of Kurdish prisoners into a kind of human sound wave crying for justice, and a new work experiments with an innovative style depicting the Nogra Salman Prison Camp in a laser cut on wood drawing.

While Ahmed’s work is inexorably tied to his experience as a survivor of Anfal, its pure humanity transcends the personal to reach a kind of universal meaning. The eyes of his figures, asking “why are you allowing this to happen?” dare the viewer to return their gaze.

“Armenians see themselves in my work,” he tells The Markaz Review. “Jews too, find themselves in the story. Palestinians find themselves inside my work. I’m talking about everywhere around the world and calling for an end to war. My style is simple. The line is representing humanity everywhere.”

Since the Anfal campaign is not part of Iraq’s educational curriculum, and “is barely touched on even in Kurdistan,” he says, many young Iraqi artists who came to see the exhibition told him it was their first exposure to the reality of the genocide.

Although Ahmed learned about the Baghdad Modern School as a young art student, he had never travelled to Baghdad and was exposed to Fakher Mohammad’s work for the first time at the exhibition.

Mohammad, born eight years before Ahmed, in Babylon, where he was Dean of the College of Fine Arts from 2017-2022, is in many ways a peer, albeit one whose trajectory and life experience ran in a parallel but separate world. Widely recognized as a pioneering figure in the Iraqi contemporary art scene, he has two degrees in painting from the Academy of Fine Arts in Baghdad, including a Master’s completed in 1980. In 2003, he earned his PhD in Modern Painting. This exhibition was the pair’s first in-person encounter with each other and their work.

Although Fakher Mohammad’s art, ranging from the abstract to the more representational, is stylistically far from Ahmed’s pen and ink drawings, Mohammad too is a product as he told the The Markaz Review of “three wars” — the Iran/Iraq war, the Gulf War and the 2003 invasion and ensuing sectarian strife. Like Ahmed’s work, his oeuvre is a form of healing and regrounding of the 20th and early 21st century Iraqi experience. It’s also a testament to the genocides in Iraq — both cultural and human.

When the Saddam Arts Centre was looted in 2003, he points out, “The US soldiers just stood by watching.” While his generation had access to art museums where they could contemplate actual work by contemporary masters, now there is a whole new generation of art students who have no access to their modernist heritage.

Inspired by the ethos of the Baghdad Modern Group, that united artists under the shared commitment of “Istilham al turath,” or “seeking inspiration and motivation from artistic heritage through innovative methods,” Mohammad excels at transforming heritage into contemporary idioms.

In the Infrangible show, he presents a tryptic of canvases fusing ancient symbols and contemporary reality. 2022’s “The Recovered Memory of the Symbols of the Earth,” blends Babylonian motifs with natural elements, employing them as talismans of protection in a war-torn world.

“I want to show that the elements — the sun, the moon and the animal world — are more powerful than humans,” Mohammad says. “They will survive after everything, and we are beholden to their power.”

In his works, doves peek out from bloodied palm trees, goddesses grow out of the Babylonian mud, and an omnipresent Mesopotamia speaks in contemporary tongues.

He is happy to be showing his work alongside Ahmed but notes that “this is not the first time in two decades there has been an Arab/Kurdish art exhibition in Baghdad.”

He recalls a group show in 2006 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, where Ismail Khayat, the iconic Kurdish artist who encoded Kurdish folklore and symbolism with the ideas of collective struggle and political isolation, and Erbil-based Mohammed Arif, exhibited alongside Arab artists.

And that was not the only one, he says. “There were always Kurdish artists exhibiting in Baghdad, even when the political situation between Kurds and Arabs wasn’t good, the art transcended all of that and brought us together.”

Mohammad himself had a solo show in Sulaymaniyah in 2019, launched by the widow of Talabani, Hero Ibrahim Ahmed (the former first lady of Iraq from 2005 to 2014), an avid collector and patron of the arts. The venue was the Amna Suraka Museum, once known as the infamous “Red Prison,” a notorious torture center under Saddam’s regime.

The exhibition was a great success, Mohammad tells me, smiling widely at the intersection of his scorched Mesopotamian earth works and Ahmed’s powerful witnessing of the Kurdish genocide. “She bought four of my paintings.”

There are works by other artists of note here tonight, including Mohammed al Kanani, whose 2025 work TV Memories is a Warholian trip down memory lane, evoking the stars of pre-invasion Iraqi television with mixed media tableaux on wood; Makki Omran’s surreal collages of what he names Overlapping Worlds that blend images of extra-terrestrials, ancient sites, American war planes, Donald Trump with a tattered Iraq flag on his arm and grieving Sumerian goddesses, that reads like an iphone scroll through history and yet somehow manages to capture Iraqi reality; Salam Omar’s recreation of blast walls that used to separate Shiah and Sunni neighbourhoods in Baghdad, in the wake of the 2003 invasion, which he has re-empowered as sculptures decorated with graffiti; Sulaymaniyah based Daro Resole’s abstract expressionist scarred landscapes of Kurdistan and Kurdish artist Salih Alnajar’s haunting abstract fragmented figures seeking wholeness; and the mystical calligraphy rich works of Karim Farhan —who emigrated to Switzerland years ago — reminiscent of Shakir Hassan Al Said’s late stage Sufi-influenced art.

The Gallery is in Karrada, a neighborhood that once symbolized Iraqi diversity, where the site of a 2016 bombing by ISIL was transformed into a pop-up shrine by Riyadh Ghenea, (the artist who initiated the exhibition). Here for a fleeting moment, the old Iraq and its federalist ideal come alive, transcending the current chaos and uncertainty to reveal the soul of a long-suffering nation.

A fine thoughtful review, filled as usual with history, compassion, and a detailed appreciation of the work. Well done!!