Watching the war on Gaza in which he lost his sister, from his home in Paris, has been hard on Batniji. But he did resume work, and the recent destruction weighs on several pieces in his new show at the Sfeir-Semler Gallery in Beirut.

“We hope that the war will stop at least,” says Taysir Batniji. In a few hours his exhibition Just in Case will open at Sfeir-Semler Gallery’s Beirut port space, running through March 25. The Gaza ceasefire of Jan. 19, 2025, has yet to be announced.

“I know it cannot bring the end of suffering,” adds the Gaza-born artist, “but at least the killing will stop.”

Watching the war on Gaza from his home in Paris has been hard on Batniji. “For two, maybe three months, I couldn’t work because of what happened to my family,” he admits. “I lost more than 60 people, [including] my sister, so it was impossible to think artistically. It was difficult to speak, even.”

He did resume work, and the recent destruction weighs on several pieces in this show.

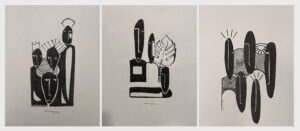

Just in Case is a relatively compact exhibition that is at once understated and powerful. A pair of older pieces greets visitors upon entering. “Untitled,” 1998-2021, is an open suitcase filled with sand. Another piece, also “Untitled,” from 1997, is a series of 20 rolled canvases, each bearing a rust imprint, as if from an oversized key of the sort Palestinians carried with them when displaced from their homes in 1948. But most of the works on show at Sfeir-Semler — abstract and figurative pieces, series of photos, sketches and paintings — are selected from the artist’s recent practice.

The strength of these pieces attests to the decades of catastrophe that resonate through Batniji’s practice. Their subtlety betrays the artist’s strategies to continue working even as occupation policies in Gaza grew more brutal in recent years.

Occupation Figuration

Batniji’s show seems understated because its images do not obviously reference Gaza. Innocent viewers might find it hard to find any references to Palestine at all. He is not happy about finding inspiration in conflict and war. Artists, he’s said, must always be careful to avoid being trapped by the political discourses and pathos that accompany conflict. In a 2012 interview, he remarked that if he were to make a work that was inspired by politics, Israel’s separation barrier, say, the work would have to “have meaning on multiple levels. I don’t want my work to be connected to specific events or situations … That’s why the poetic dimension of my work is very important.”

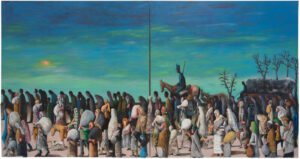

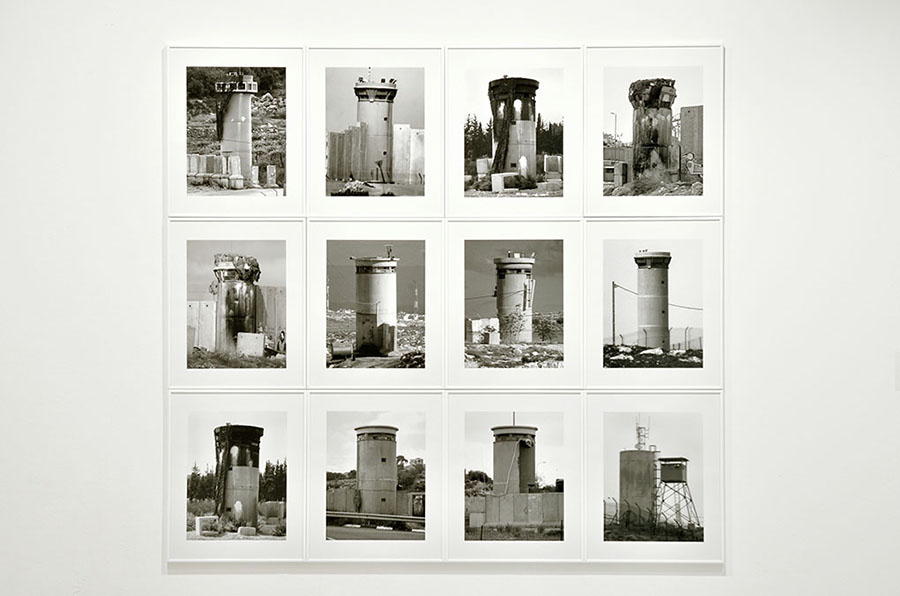

The artist’s past work has used images and materials that have become emblematic of contemporary Palestine — a photo series of occupation infrastructure (Watchtowers, 2008); a palette bearing dozens of bars of soap stamped with an ambiguous Arabic aphorism (“No Condition is Permanent,” 2014); a suite of short videos in which Palestinian emigrants in America tell their stories (Home Away From Home, 2017). Throughout, Batniji has prioritized aesthetic and humanist criteria over partisan ones, in hopes that the work speak to a public outside Palestine as well as within.

“I worked on watchtowers because they were problematic and I found connections with art history,” he said in 2012. “Of course, I hope that the work denounced the occupation, but it came from inside the work. It was not my decision to decide to make a work about the war. It is important to me that the work inhabits different readings and that it is not limited to one reading, only a political, only a demonstrative reading.”

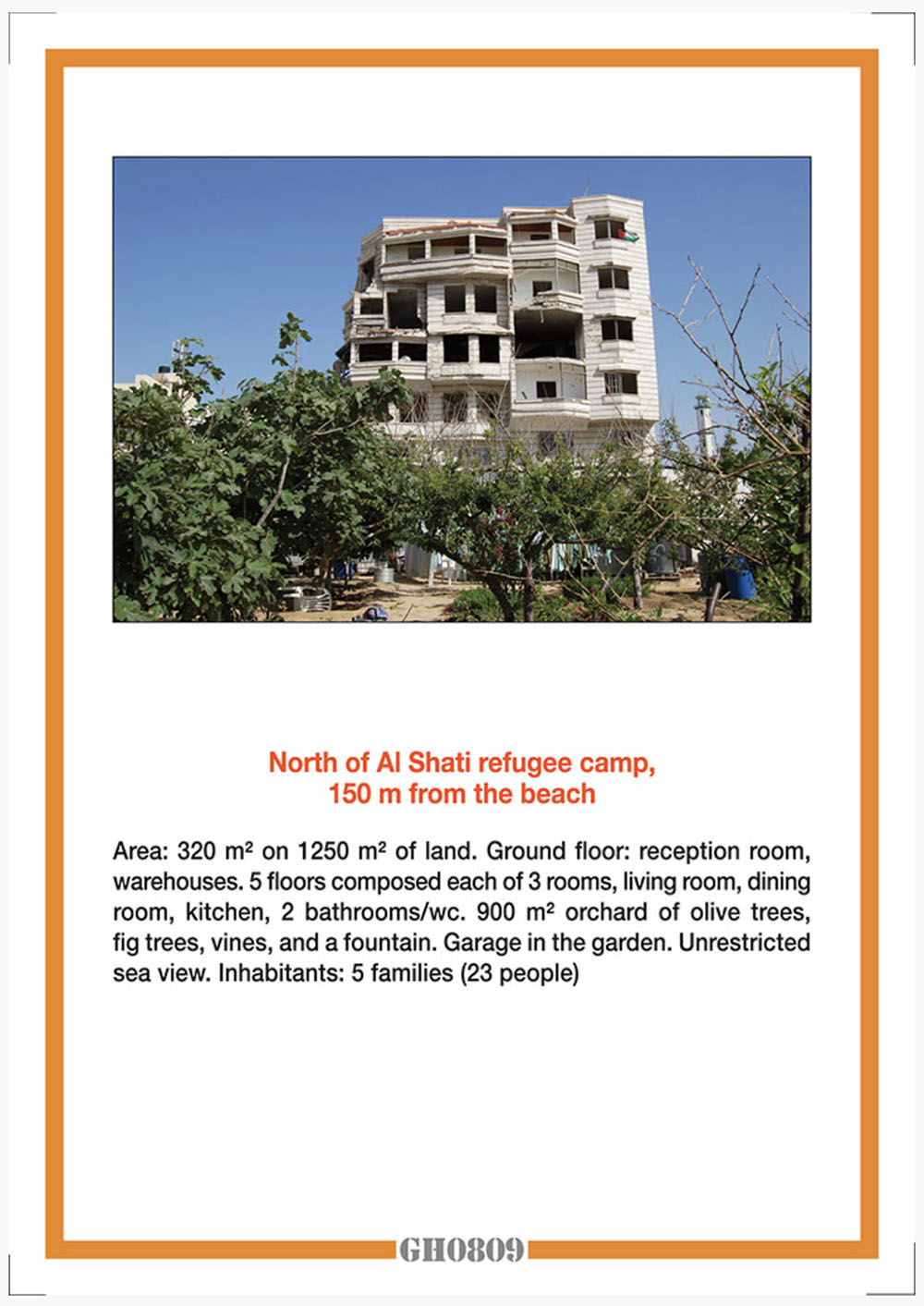

A favorite target of Israeli military attacks has been Palestinian homes. This theme inspired Batniji’s “GH0809 #2” (Gaza Houses 2008-2009), which pairs a series of photos of war-damaged domiciles with real estate ad-style descriptions of each property’s dimensions and layout.

Echoing “GH0809 #2,” the titular work of the Sfeir-Semler show, the photo series “Just in Case #2,” 2024, derives from ruined residential properties in Gaza whose owners were displaced during the 2023-2025 genocide. The photos don’t frame the structures themselves but the owners’ keys — thus addressing “Untitled,” 1997, on the other side of the gallery. Rather than riffing on real estate dialect, the work’s textual accompaniment recounts the fate of each home and homeowner.

Though some homeowners died in detention or during attacks on their premises, the accounts are bereft of emotion.

“Alaa al-Din Mahmoud Jaber, a resident of Zeitoun in Gaza,” reads the caption beneath a photo of a lone key. “He left two days before the truce of November 24, 2023, and sought refuge in Tal al-Sultan in Rafah. His house was destroyed on January 6, 2024.”

“Muhammad Salah Zaarab, a resident of Beit Lahia, north of Gaza City, was displaced on November 10 to Rafah,” reads another. “His home was raided on November 4, 2023, injuring several people.”

Several photos bear the caption “Information not available.”

Recorded in Batniji’s hand in pencil, the textual elements of this series collude with the photographic to make “Just in Case #2” intimately gestural and ephemeral. Given the ruthless scale of death and destruction meted out to Gaza’s residents — the video documentation of which is impossible to digest in any meaningful way — the best the artist can do is show the mundane residues of lost homes and, using erasable graphite on the frail medium of paper, uniquely register a few details of these evanescent lives.

The show’s other figurative work is “Fading Roses,” 2022, a series of A4-sized watercolor-on-paper pieces. The artist’s decision to make red his primary color accentuates the inherent fragility of both the form and its subjects. There is nothing typically “Palestinian” about this work, yet 15 months of social media and television news videos testify to how impermanent is peace, how delicate is life.

Necessary Abstraction

The more challenging works of Batniji’s recent practice — and the most informative of the creative trials he’s undergone recently — are his non-figurative pieces.

The artist says abstraction has been an important part of his practice since 2021 when MAC VAL (Musée d’art contemporain du Val-de-Marne) staged a retrospective of his work.

“I don’t know why I’m working on these iconoclastic works,” he reflects. “I’m still analyzing this.”

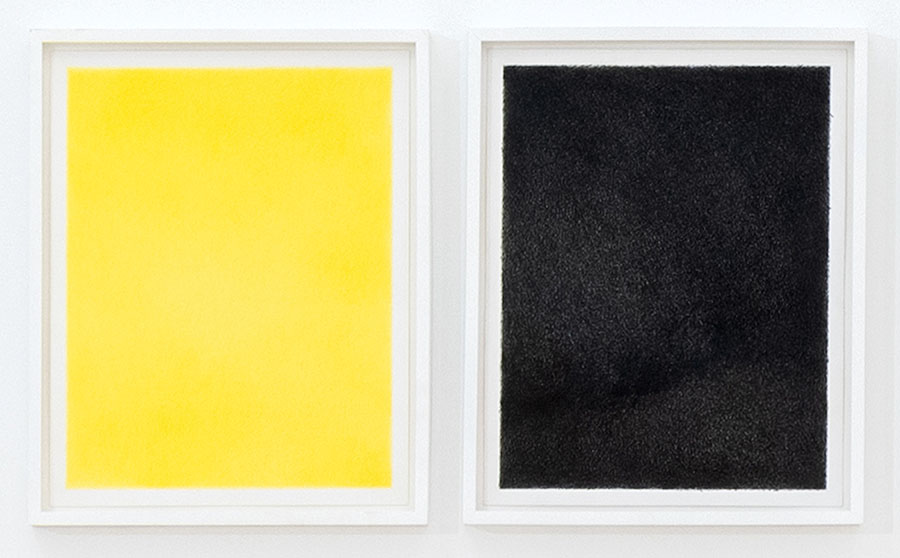

The origin of the 2024 series Out of the Blue is accidental mobile phone photos — the epitome of fleeting banality — which he reproduces using pastels on paper.

“It’s a way to [to give mechanically produced images] another duration …” he explains. “These accidental photos were taken in fragments of seconds and take hours to be drawn, so I give them more time and make them material — taking them from a virtual space to a material space.”

Just in Case is also showing a few oil-on-canvas abstracts, taken from the 2024 series Remnant, which originated in sluggish downloads of Telegram newsgroups. This was Batniji’s Gaza news source when Israel set about ethnically cleansing Gaza in October 2023.

“Sometimes they are images of real horror — massacres, pieces of corpses — so before an image downloads fully, I make a screenshot. This is what I try to reproduce on canvas.

“To stop the image before it downloads is to prevent it happening,” he suggests, smile contorting into a grimace, “but you cannot, because the image is, by definition, a trace of what is happening.”

In the case of “Homeless Colors,” 2024, another series of works on paper, both the image and the materials hinge on chance.

It grew from Grounds, an ongoing project commenced in 2008, in which Batniji photographs random items he’s found on the ground while walking through Paris. One day in 2023 he stumbled upon six Bic pens.

“Usually Bics come in four colors — green, red, blue and black — but this package also had yellow and violet,” he recalls. “I took them to my studio and tried to estimate how much ink was still in them and how much paper I’d need to empty each one. I tried applying each color, layer upon layer, [to a roughly A4-sized sheet] until emptying the pen. Sometimes I covered it 100 percent. Sometimes less.”

The project continued when he found some colored pencils on the street. He also foraged a bagful of crayons. “These works,” he says, are concerned with “two processes — making the work itself, but consuming the material, the found pencil or the Bic, becomes just as important.”

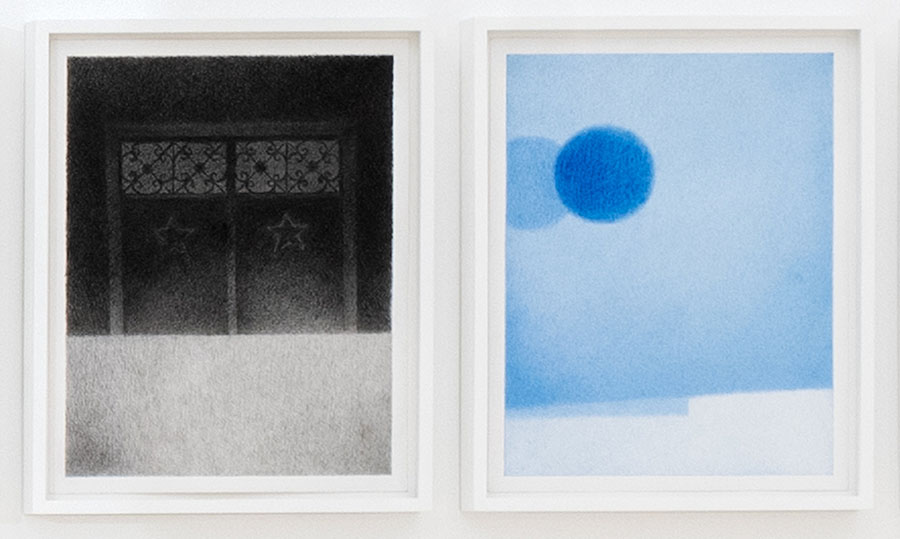

Some of the “Homeless Colors” on show at Sfeir-Semler are figurative, other not.

“At the beginning, I tried to take inspiration from the color itself. When you make the first layer, you may start to see shapes.” He gestures to a white-and-blue work that resembles sky dappled with white clouds. “I try sometimes to follow the shapes I see or imagine.”

Batniji nods to a nearly monochrome black panel. “Here, I tried to imagine a fragment of a nighttime scene, like from the corner of a garden with some trees.”

One of the more easily identifiable depictions is an incomplete black-and-grey rendering of a door topped with a latticed window. “This was the door of my mother’s home, which is now totally destroyed, in which some 22 people were killed in one strike — ”

The artist’s voice quavers briefly and pauses. “Finally, I decided it really was not the time to think about [such matters] … Why should I try to find a way to draw a form? So I decided just to make monochromes.”

Batniji turns to a blue sketch of a dark sphere upon a lighter background that he completed on Oct. 5, 2023. The sphere, he confides, “was not in the original drawing. Later, I decided I wanted to correct something and destroyed it, in fact, because I’d wanted just to have monochrome … I’d spent maybe a week, every day, working on this drawing and suddenly I just destroyed it because I was a perfectionniste.

“When October 7 happened, I forgot all about this. We entered another dimension …” He pauses. “In these drawings I found some equilibrium, so I could concentrate. I could feel, at least, that I’m doing something, not just following the news and calling the family, trying to get news. I continued to do this, but while drawing. Maybe it made the impact of things less hard.”

Batniji says it may be that he needed to step back from the unremitting stream of images detailing the relentless military erasure of Gaza, but insists that abstraction and figuration coexist in his practice.

He nods at the wall at Sfeir-Semler devoted to “Just in Case #2” —the series showing the keys of Gaza’s ruined residential properties.

“I also return to this ongoing work. It helped me, these transitions, these moments, to find some concentration and maybe to think about other projects. Maybe while doing [“Remnant”] I could think about [“Just in Case #2”].

“So the reality catches us again. You cannot escape it or avoid it.”

Nearby, the gallery manager is measuring the pieces hanging on the space’s western wall. He blinks and tells her the works’ dimensions in French.

“This exhibition makes a kind of tabula rasa of what I did before.” Batniji turns to survey the room. “That doesn’t mean that I [forsake my earlier work]. I can still build on that, but I felt that I have to question my work more. I needed this time of emptiness.”

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)