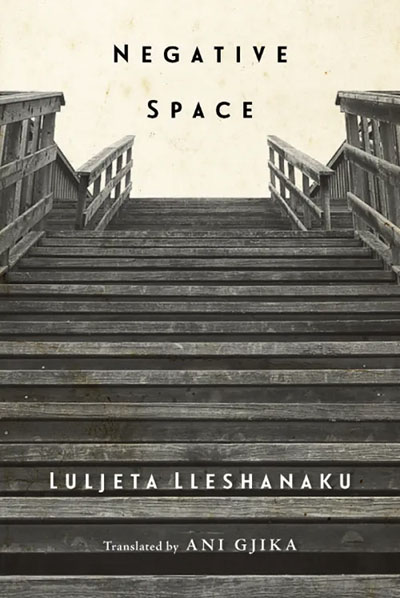

Poetry Markaz presents two poems from Luljeta Lleshanaku’s latest book of poetry available in English, Negative Space, published by New Directions in the US and Blood Axe Books in the UK, and translated from Albanian by Ani Gjika.

As New Directions notes, Lleshanaku’s “personal biography disperses into the history of an entire generation that grew up under the oppressive dictatorship of the poet’s native Albania…the ‘unsaid gestures’ make up the negative space that ‘gives form to the woods / and to the mad woman— the silhouette of goddess Athena / wearing a pair of flip-flops / and an owl atop her shoulder.’ It is the negative space ‘that sketched my onomatopoeic profile / of body and shadow in an accidental encounter.’ Lleshanaku instills ordinary objects and places—gloves, used books, acupuncture needles, small-town train stations—with subtle humor and profound insight, much as a child might discover a world in a grain of sand.”

As New Directions notes, Lleshanaku’s “personal biography disperses into the history of an entire generation that grew up under the oppressive dictatorship of the poet’s native Albania…the ‘unsaid gestures’ make up the negative space that ‘gives form to the woods / and to the mad woman— the silhouette of goddess Athena / wearing a pair of flip-flops / and an owl atop her shoulder.’ It is the negative space ‘that sketched my onomatopoeic profile / of body and shadow in an accidental encounter.’ Lleshanaku instills ordinary objects and places—gloves, used books, acupuncture needles, small-town train stations—with subtle humor and profound insight, much as a child might discover a world in a grain of sand.”

Luljeta Lleshanaku

INDEX

Days were never this long before.

Their whiteness a lactose too difficult to break down.

He dozes wherever he can. Gets upset only when lunch isn’t

ready on time.

Speaks a little less each day and moves from one sentence to

another

without argument, as if drifting between rooms in a house without corridors.

Yet sometimes he asks questions like:

“What did God have in mind when he made man?”

A rhetorical question you don’t need to answer.

He falls asleep as fast as a book that drops from his hand.

It is said that the most ordinary among us is a written book

that exists in heaven, a book so huge

that human eyes cannot read it.

That’s where everything

is recorded—what we’ve done, said, thought, felt,

even what hasn’t happened yet. Who could imagine

that a human body—some square centimeters

that were once only a cell—

could contain so much space for history?

He understands other people less, including his wife,

the book he’s lived with cover to cover

written in two different languages and placed on the shelf

according to the index.

SOMETHING BIGGER THAN US

The Eskimos have numerous different words for “snow”:

the freshly fallen, the stepped on, the aged,

the piled up in heaps, the rotten one

left over from the previous winter.

As if nearsighted,

they’re able to distinguish different shades of white:

the nothingness, the emptiness, the present of an eternity,

and the eternity of the present.

Where I come from,

we have four different words for “evening.”

Funny, but the one that fits best

is borrowed from a foreign language

brought over by invaders, not by spice merchants,

and it rhymes with “lilacs.”

Where I come from,

there’s only one word for “grief ” and for “water”

and both take the form of the containers that hold them:

each to their own fate, each to their own grief.

The Greeks have four different words for “love,”

like the four stakes of a tent

that assure you a spot in this world

if not today, maybe tomorrow.

According to anthropologists,

until a century ago, my people

had no word for “love,”

only a clever, naive doubt:

“It’s something bigger than us, right?”

A doubt performed with the rhetorical gesture of a king

who asks questions and expects

answers to arrive only in his dreams.