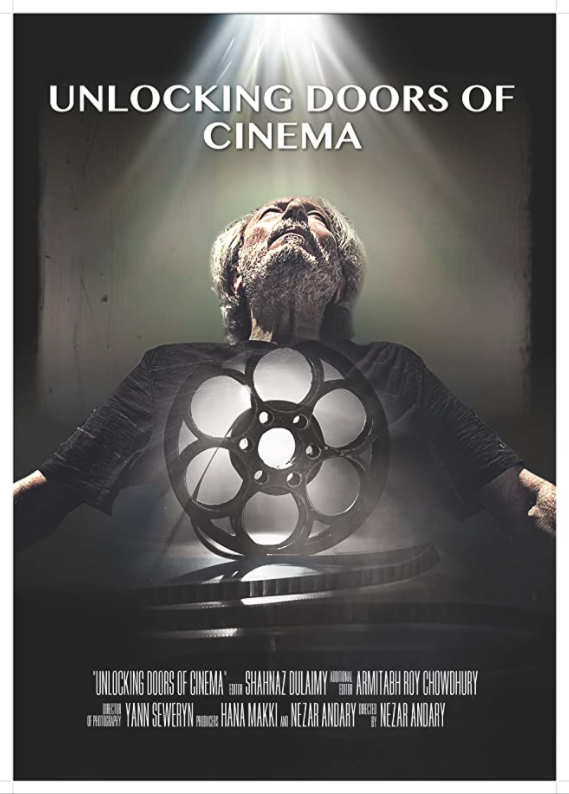

For his first feature-length documentary, Abu Dhabi-based academic and filmmaker Nezar Andary sought to explore the work and life of Syrian-born legend Muhammad Malas, as a means of taking the viewer on a tour of Arab auteur cinema. Unlocking Doors of Cinema is a warm-hearted homage to Muhammad Malas’ pioneer spirit, as well as a reckoning with a generation of engaged intellectuals whose collective cultural efforts and intensity of purpose paved the way for the latest generation of Middle East filmmakers. From the 1967 War and Palestinian camps in Beirut, to the songs of Aleppo, and the political tragedies of Syria in recent years, Andary argues that for five decades now, Malas “exemplifies what it means to be an auteur and public intellectual.” A writer, filmmaker and Associate Professor at Zayed University in the United Arab Emirates’ capital, Abu Dhabi, Andary also edits a book series on Arab cinema for Palgrave, where he co-authored The Cinema of Muhammad Malas, Visions of a Syrian Auteur (Palgrave 2018) with Samira AlKassim. It is this book, combined with 12 hours of interview footage with Malas and dozens of hours from Malas’s oeuvre that shape a film about a director who “listens, sees and hears cinema.” The 60-minute documentary was shot in Lebanon where the 16th century Talhouk Castle provided a worthy backdrop for a conversation on memory, loss, regret and hope. “The house was perfect,” commented Andary when we spoke recently on Zoom. “It played a huge part in lending a haunting atmosphere to the film, which I felt remarkably mirrored Malas’s lifelong sense of exile. “My aim was to allow the documentary to be haunted, in a positive way, by Malas’s films and also by films that haunt his work as well,” Andary said. “Even the title is an homage to Malas’s work, drawn from researching the amount of doors that open, close and lock in his movies, which he uses to represent larger metaphors or allegories on some level tied to times and places we haven’t seen or been able to recover due to regional conflict. Ultimately, what I hoped for was to end up not only with a documentary about a great Arab filmmaker but also with a film breathing cinema itself.” Showcasing Unlocking Doors of Cinema on the film festival circuit as we begin to reconcile ourselves with the 10th anniversary of the thwarted Thawra or Arab Spring revolutions, could not have been more timely—not only amid the continued unrest in the Middle East but also as political analysts and individuals from the region and outside it look back to scrutinize the past decade since Mohamed Bouazzi immolated himself in Tunisia, sparking uprisings across the region. Andary’s documentary hones in on Malas’s obsession with examining personal and collective memory of social and political trauma and dispossession in his films. If anything, the documentary demonstrates that the region’s quest for justice is nothing new, for Malas’s films portray decades of rebellions against despotism, as his protagonists struggle to overcome obstacles even as they expose hidden truths. It is Andary’s excavation of the filmmaker’s past work— including the 1967 Arab-Israel war in Quneitra 74, The Memory (1975) and Dreams of the City (1984), Palestinian refugees in Lebanon camps in The Dream (1980-81) and The Night (1992)—up until the more recent Ladder to Damascus (2013), that not only allow expansion of the discussion regarding the region’s tumultuous history but also foregrounds Malas’s pivotal significance and relevance to this day as guardian of Arab auteur cinema and its ever-evolving advocate. Cinema, as Andary’s documentary seems to propose and which Malas’s lifework corroborates, is how we learn to remember and reflect on the past, and together, oppose the natural disposition of society to forget. “All that is forgotten,” says Malas to the camera, “dies.” Born in Quneitra on the Golan Heights in Syria, Malas was son to the carpenter who roofed the town’s sole cinema where the filmmaker caught his first film The White Rose (1933) featuring Mohamed Abdul Wahab. When he was nine years old, his father died, and he was forced to leave town with his mother to live with her family in Damascus. It was not long after that the 1967 war with Israel broke out and his beloved city fell under Israeli control. Israel continued to control Quneitra until early June 1974, when it was returned to Syrian civilian control following the signature of a United States-brokered disengagement agreement. The city remains destroyed to this day. Malas’s return to his ruined hometown in many of his films suggests a loss from which he has never recovered. “It is safe to say that in a way akin to survivor’s guilt, everything for Malas goes back to Quneitra. His relationship to the abandoned place is something of a metaphor to his lost childhood,” Andary explained. As such and calling to mind Henri Lefebvre’s reflections on history, time and memory, Malas’s films appear as attempts at remembering happy spaces of the past that articulate a desire to somehow regain them. That said though, Andary is mindful of a “false nostalgia” that unlocking a place and looking at it directly “in memory” can result in. However, “within this false nostalgia,” he explained, “is still an act of looking for something that might have been better from a different perspective than what we presently have.” Malas studied cinema in Moscow for five years where he found his inner voice in auteur cinema. Surrounded by important intellectuals of the time, one of whom was his roommate, Egyptian novelist Sonallah Ibrahim, who later appeared in Malas’s graduation film Everything is Alright Mr. Police Officer, set in an Arab jail cell. In it Sonallah recalls his seven-year jail sentence ordered by Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1959 for his membership in the Marxist Democratic Movement for National Liberation. An Arab leftist, Malas believed in the nationalist project and the rights of the Palestinians to return to Palestine. “So much so,” said Andary, “that I would go so far as to call him a Palestinian filmmaker.” His documentation of the plight of the Palestinians forced to leave their lands after 1948 to seek refuge elsewhere was the reason he shot a documentary film, al-Manam (The Dream) (1980-81), about the Palestinians living in the refugee camps in Lebanon during the civil war. The film was composed of interviews with the refugees in which he asked them about their dreams. In the documentary Malas explained how the stories unveiled myriad images of a Palestine that those who were forced to leave carried in their hearts. That’s not to say that Syria was not ever his ultimate concern. It was. In fact, as ever the engaged Arab citizen, in 2013 Malas took to the streets of Damascus to document the protests demanding change and freedom in a film he later named Ladder to Damascus, describing it as “a song of courage to the Syrian youth.” What sets it apart from his other work in Syria is not only the danger involved in the making of the film but also his own disbelief at how differently things turned out for the region from what his generation had hoped for. Commenting on Ladder to Damascus in the Andary documentary, Malas laments the failure of his generation in so many ways for being unaware of the realities in Syria and for “not having the foresight to address all the possibilities that could one day become realities.” He is, however, not without hope. He believes “this generation with all the tools it has at its disposal and its openness of vision equips it to see through things and to resist.” Malas still lives in Damascus despite the challenges of the civil war that has cost Syria so many lives and much of its stability. While he has done a prison stretch and has seen certain of his films banned by the government, his work, Andary says, is well-known and respected across the Arab world. As for Andary, after leaving Lebanon with his family during its civil war (1975-1990), he grew up in several Arab countries before going on to earn his bachelors at Columbia and his PhD at UCLA. An Associate Professor at Zayed University, over the last four years Andary has produced more than 10 documentary shorts for the Arab Film Studio that have screened in over 50 festivals. His recent publications include a work on Anthony Shadid, Homage to Anthony Shadid: Literature of a Journalist, as well as a study on Ibn Khaldun in contemporary culture and theatre, entitled Confronting the Symbol of the Intellectual. These days, as his Malas doc tours the film festival circuit, Andary is focusing on his role as artistic director of the forthcoming Al Sidr Environmental Film Festival in Abu Dhabi, and he has co-curated a series of films for the Manaarat Saadiyaat Museum and Exhibition Center. In effect, what filmmakers Nezar Andary and Muhammad Malas have managed to achieve with Unlocking Doors of Cinema is what all docs, first and foremost, are supposed to do and that is to inform. However, a documentary is still a film, after all, and therefore a piece of art and Andary’s film is a gem—a meditation on Malas that has the incredible nuance and wherewithal of being able to tell a story at the precise pace that both artists require, revealing information only when and where it creates the most meaning for the audience and for the film as a whole. It is one that allows its viewers the space to think freely and to deepen their understanding of the subject and of themselves and to walk away with a conversation that will resonate well after the screening.

Rana Asfour

Join Our Community

TMR exists thanks to its readers and supporters. By sharing our stories and celebrating cultural pluralism, we aim to counter racism, xenophobia, and exclusion with knowledge, empathy, and artistic expression.

Learn more

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)