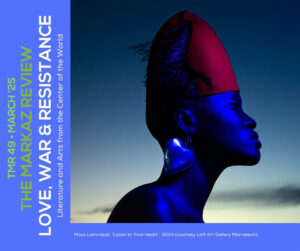

As London emerges as the unofficial capital for Persian media outside Tehran, threats abound and so do breaking stories.

Malu Halasa

Last month, seven armored response vehicles filled the streets of a sleepy London suburb after the Metropolitan Police informed Iran International TV (IITV) of “a credible and significant” threat against two of its journalists. The seriousness of the intelligence prompted U.K. foreign minister James Cleverly to summon Iran’s most senior diplomat to the Foreign Office. The conversation wasn’t made public, but the outraged pronouncements of British officials afterwards suggested the U.K. government didn’t take kindly to the intimidation of journalists by a foreign power on its patch.

These days, the 24 hour Persian, non-regime satellite channel IITV broadcasts from behind a fence and a three-meter high concrete barriers, which can stop a seven-and-a-half ton truck at 60 miles an hour. No cars are allowed into the vicinity; metal detectors, armored response vehicles and police protect the site. Private security guards control entrances. My name was on a list, and the young man who escorted me to the offices of Volant Media, IITV’s parent company, came from the garrison town of Aldershot, which suggested a private security firm with access to freelance British squaddies (GIs).

Upstairs Adam Baillie, a news producer who helped set up the channel in 2017, explained that the two threatened journalists, still unnamed, are now under police protection. “There’s low-level harassment against families inside Iran – that’s a given,” he explained, “The IRG (Islamic Revolutionary Guard) commander-in-chief Hossein Salami said, ‘We’re coming for you.’ They’ve had us under surveillance. Given the opportunity, presumably they would strike.”

The Revolutionary Guards aren’t the only ones watching IITV, and the other Farsi-language TV channels and news websites, including BBC Persian, Manoto TV and IranWire — all based in London, which has emerged as an important hub for the Persian press outside of Tehran. Since September 16th this year, when nationwide protests erupted in Iran after the beating and death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, increasing numbers of viewers and website users inside the country have deserted state-controlled media to seek news and information elsewhere.

Threats in the past and present, veiled or otherwise, color the experience of Persian-speaking journalists in London. Many take precautions as a matter of course. Some BBC Persian personnel keep their place of work secret. At Manoto TV, phone and email messages go unanswered. The 2009 detainment, arrest and subsequent release of former Newsweek reporter Maziar Bahari at IranWire are well documented. Along with Voice of America (VOA) Farsi in Washington D.C. and Radio Farda, part of Radio Free Europe/Liberty Radio service, in Prague, the international Persian-language media outlets, which beam into Iran, pose an existential threat to the Iranian regime. The government’s pushback is an indication of how seriously Tehran takes the information war for the hearts and minds of ordinary Iranians.

A woman broadcast journalist who fled the country last month requested anonymity before speaking with me. “Iranians have more trust in a video or photo they see published on Instagram or Twitter than any media related to the government,” she said, “and they tend to search for news in other countries.”

She was also keen to stress that none of the Persian news networks have correspondents or reporters inside Iran. They too are reliant on the news Iranians at home post on their Instagram accounts.

IITV’s Baillie agrees. The channel relies on UGC (User Generated Content) in addition to the informal connections of the channel’s 350-strong staff inside the country, and their reporters living outside. The channel also broadcasts from Washington D.C., with journalists covering the U.N. in New York and the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) in Vienna. “Our mission is not to foment revolution, or pick and choose stories that are uncomfortable for the authorities in Iran. As an independent news channel, we mirror back to Iran what’s happening in Iran, and Iran-related, international stories.”

On Saturday morning, few seats are empty in front of the array of computer monitors on rows upon row of long tables, which fill an open-planned newsroom. Screens on the walls broadcast IRIB (Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting). At one end is a television studio. Somber, in black, anchor Parisa Sadeghi prepares to go on air. She sits in front of a larger-than-life still image of women protestors holding each other’s hands in the air.

Recently news inside Iran’s corridors of power has been coming from Black Reward, the Iranian hackers’ group, which introduced itself on Telegram in October with a spectacular treasure trove of documentation from the country’s nuclear agency. In October, the group sent an SMS message to five million Iranians, calling them out onto the streets.

Baillie said nobody at the channel knows them. However, the group is a professional outfit and not made up of “teenage activists.” Because of the channel’s popularity inside Iran, IITV has become the hackers’ “first port of call” and, he stresses, “that’s not at our behest.”

Last month, the group released an audio file of a meeting between the Basij commander and IRG’s General Salami, and a treasure trove of archival material from the regime’s propaganda arm, Fars News Agency. Dubbed “Farsgate” at IITV, the hacked emails revealed the pressure Iran brought to bear on Qatar during the World Cup to cancel the official FIFA accreditation of the channel’s sport reports, which barred them from the event.

The Iranians also reminded the Qataris that the border with Iran was only forty miles away, and if the channel’s reporters did come, they might be persuaded to “prolong their stay” in the region – i.e. be kidnapped.

Before the Netherlands/U.S.A match, Baillie introduced me to a roomful of IITV sports reporters. When I asked if they were upset not covering the World Cup, one cried out, “Better to be alive!”

IITV has 11 million followers on Instagram, and features stories that don’t find a home on family-oriented channels like Manoto, which means “You and me” in Persian, and has been known to broadcast lengthy documentaries on the Shah’s wife, Empress Farah. The different audiences of Persian media outlets are reminiscent of the division between the sensationalist New York Post and the more traditional New York Times.

The hackers collective Black Reward leaked security camera footage inside a Fars News Agency office. An editor locked his office door, smoked cigarettes and ate potato chips while surfing the net and jacking off. The footage went viral. It was one of the most read stories trending among readers of its English-language website, which closely mirrors its Persian site.

This channel and the other Persian media organizations are not inexpensive propositions and the sources of their funding have made them vulnerable to criticism. The British Foreign Office funds BBC Persian, as does the U.S. government for VOA Farsi and Radio Farda. A British Saudi businessman funds IITV, which was accused by the Guardian of having ties to the kingdom’s effective ruler, Mohammed bin Salman – allegations that were strenuously denied by the channel.

“There is no editorial interference,” shrugged Baillie, “No hotline between us and anyone else.” To prove his point, he turned to the channel’s coverage of the murdered Saudi dissident and journalist Jamal Khashoggi. IITV broadcast the first interview with Agnes Callamard, the U.N. Rapporteur on extrajudicial executions. “If anyone was pulling our editorial strings, they’d make us cover the story in a different way.”

Breaking the News

A New York Times’ story on the shutting down of Iran’s Morality Police – responsible for policing Iranian women – by Middle East bureau chief Vivian Yee and Farnaz Fassini, on December 4th, suggested the regime had made a concession to the protests. But Iranians on Twitter and Middle Eastern news outlets criticized the analysis. The next day the New York Times backtracked by publishing another article explaining why “the concession” might be a red herring. The newspaper’s coverage of Iran was a lesson on how not to be stooge for the regime at a time when women protestors are being shot in the face and genitals.

The website IranWire breaks important stories by forensically dissecting events inside the country, finding and checking sources and understanding the regime’s modus operandi. The platform’s work has not gone unnoticed. Last month, the Washington Post called it “an essential player using technological savvy and internet sleuthing.”

IranWire’s Aida Ghajar was the first reporter to write about Mahsa Amini’s death after seeing tweets from initially unnamed and then named sources, both inside and outside the country. The trail Ghajar followed led to Mahsa Amini’s brother, who brother told Ghajar: “‘I have nothing to lose. Please use my name in the report.’”

This story so outraged the Intelligence Organization of the IRGC and the Intelligence Ministry, two women journalists who had no connection with IranWire other than they were covering the story in Iran were arrested. The jailing of Niloofar Hamedi from Shargh newspaper and Elaheh Mohammadi from Ham Mihan prompted IranWire to post: “How Did IranWire Publish the First Report about Mahsa Amini.”

In it Ghajar revealed the extent of her reporting, while IranWire’s Persian editor Shima Shahrabi shed light on the website’s verification process. One of Shahrab’s contacts was a “former police employee who still maintains special relations with the police …”

IranWire’s editor-in-chief Maziar Bahari was also quoted in the piece: “For the safety of professional journalists in Iran we never contact them. However, we are in contact with many citizen journalists, and they help us in our reporting, including when we report on breaking news.”

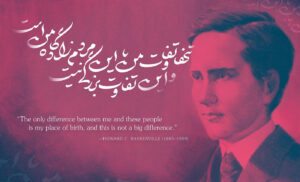

Bahari and I have known each other since the late 1990s. The launch for the anthology we coedited together, Transit Tehran, took place during his 118 days in solitary confinement, in Evin Prison. After his release, he started IranWire in 2013, which publishes in six different languages – the main ones being Persian and English, alongside Kurdish, Azari, Arabic and Spanish. The platform has a reach of 70 million people, with 90 per cent of its readership inside Iran. Some 65 per cent are between the ages 18 and 35.

Since Mahsa Amini’s death, IranWire has experienced a 225 per cent increase in users, with approximately 200 million monthly online impressions – whenever a user follows through and clicks on a website.

Other than reporting, professional journalists at IranWire have another raison d’être. They act as mentors for citizen journalists inside the country. Bahari explained, “It’s mentorship about storytelling: character development and context. Even news pieces have to be a character-based story. So basically, you’re asking people to tell a story when they send in an article or news piece or a video.”

IranWire places a strong emphasis on human rights. “We try to be correct and accurate, but at the same time we don’t pretend to be neutral,” maintained Bahari. “We are very pro-human rights. We also think about our articles, videos, any of our content, as advocacy tools for activists. So when activists want to raise the issue of, for example, the killing of children in Iran, we want to do a report that activists can use. It’s always in the back of our minds. We have that mandate.”

Mandates differ in the Persian media outlets in the West. BBC Persian, the best-known foreign media brand in Iran, has 13.8M people on average each week across TV, radio and digital platforms, and prides itself on impartiality, a stance explained on Twitter, in Persian and English. “Out sole aim is to report the truth about Iran in an independent and impartial way …” Yet, in the current climate some Iranians prefer that a side be taken – understandably against the regime.

For Bahari, the impartiality of BBC Persian shows their “professionalism.” More importantly, the ongoing protests have strengthened the links between inside and outside the country.

He explained, “It’s a two-way connection. We’re inspired by what the people are doing [there] and how they get information and use websites to communicate with each other and the rest of the world.”

But connectivity relies on access, and the Iran government has been adept at slowing down internet accessibility. As Bahari outlined, “Internet censorship happens on several different levels of Iran. They narrow the bandwidth, so people have slow connections. Sometimes they cut the national internet so people don’t have access to sites that require a cloud like Google, Twitter or YouTube etc. Sometimes the national internet connection is shut down. So even government offices and ministries cannot communicate with each other.”

The level of control depends on the unrest. In Kurdistan in the country’s northwest, for instance, when intense fighting has been taking place, the government closed phone lines. The Kurds, however, still had access to a signal from Iraq, on the other side of the border.

Dodgy VPNs

Hooman Askary, the senior social media producer at Radio Farda – which means “tomorrow” in Persian – monitors internet speeds and disruptions in Iran. Farda is one of 27 language services that Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty broadcasts to 23 countries that stifle press freedoms. By blocking access to Instagram, the Iranian government impedes communication between its citizens inside the country and slows down dissent.

“If you look at the mobile phone of the typical, middle-class Iranian you would find all sorts of messaging applications,” said Askary, “Just in case one of them doesn’t work, they try another one.”

To keep communicating, Iranians download VPN (virtual private networks), which they switch between. Askary cited former Iranian president Ahmadinejad. “He was asked about the internet filtering in Iran and laughingly he said, ‘The Internet is not filtered in Iran because those who block and filter Internet sell anti-filtering software themselves.’”

VPNs have become a lucrative business in Iran. “If you don’t get your VPN from a trustworthy source,” Askary noted, “you are not able to tell as common Internet user that your data is safe and is not being sent elsewhere using your very own Internet connection.”

He recalled a tactic of the government’s during the cost of living demonstrations that took place in December 2017. After Telegram was blocked, a few versions of Telegram emerged on the Internet. Through an application called “Golden Telegram,” a user could access all the material from Telegram but only through the filtering, monitoring and surveillance of the intelligence organizations.

Again, Black Reward provided real insight into the thinking of the Islamic Republic. Askary translated into English one of their hacked bulletins, which he sent to his colleagues at Radio Farda that morning.

“According to the result of a recent survey by the Ministry of Interior, 25 per cent of people inside Iran get their news and information from the state television and radio; 24.6 per cent receive their information vis-à-vis from the news of social media; 16.4 per cent from satellite channels; 11.1 per cent from their friends and 6.4 per cent from websites and other news media.”

He went on to say, “They have not mentioned the remaining percentages, but the figures are quite significant. They are in effect admitting that the number of people who receive their news from state television – with all the budget [and] funding [that goes into a] huge network all around the country – is almost the same number for Iranians who receive their news from social media – and this is according to the very sources of the Islamic Republic.”

He drew an analogy between Iran now and the Arab Spring. Egypt’s was called the Twitter Revolution. Even though the country’s literary rates were not high, the people who accessed Twitter were the ones who influenced their family members, peers and social groups. “So you have to remember this 25 per cent in Iran who receive their news from social media are mostly the young generation, the educated. Each one has a social network around them. The actual percentage of Iranians influenced by social media should be much higher” than statistics provided by the Islamic Republic.

Iranians on the street have made no secret that they have been let down by their state media. One of the slogans shouted during the demonstrations has been: “Our shame, our shame – state television and radio.”

Some of those who watch Iran from afar believe the current protests are different from those that have come before. Bahari, from IranWire, called them “the most seminal in the past four decades,” while Radio Farda’s Askary wondered out loud if the smaller demonstrations, which took place in the country over the past five years – of retirees, factory and oil workers, students, among many others – were just a warm-up to the unrest taking place now.

He asked, “Unwittingly, did the Islamic Republic teach and train people in mastering the art of protest?”

Speaking from Prague, he told another story. “At the beginning of the Islamic Revolution, supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini famously said, ‘My soldiers right now are in cribs,’ referring to the children who were born just after the revolution. Those very children turned into us. We did not manage to topple the regime. Many of us left the country. Many of us died. Many of us are being crushed inside Iran under the pressures of daily life.

“But this new generation,” Askary concluded, with an ominous tone in his voice, “they didn’t turn into his foot soldiers.”