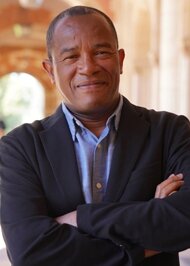

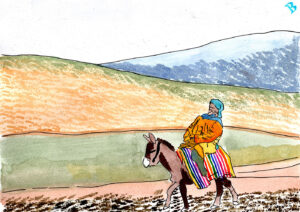

Aomar Boom describes the centrality of donkeys and mules to life in the unforgiving earthquake-shattered terrain of the High Atlas Mountains.

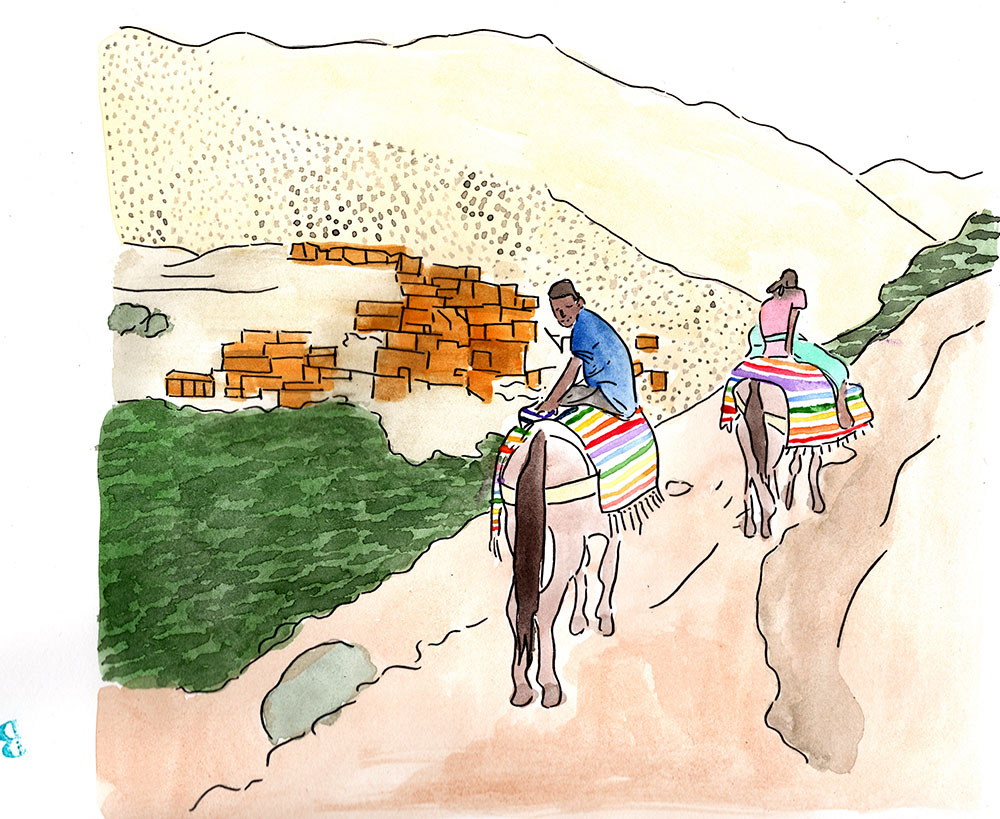

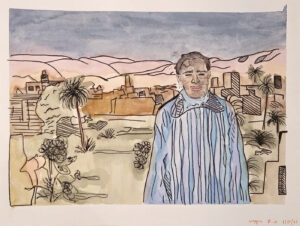

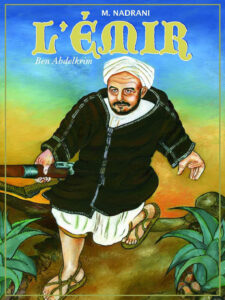

Illustrated by Majdouline Boum-Mendoza

For years now, my wife and daughter have occasionally indulged in a playful game, asking me to choose my favorite animal. Naturally, this inquisition primarily serves as a gentle, albeit annoying, reminder of their ardent desire to welcome a canine companion into our lives. My steadfast response, unwavering throughout the years, has been the donkey. I grew up with donkeys and mules, and I came to appreciate these creatures as the incarnation of patience, resilience, endurance, and labor.

Since the cameras documented the aftermath of the 6.8 earthquake that turned the High Atlas Mountains upside down on September 8, 2023, the internet has been flooded with memes that involve these beasts of burden. Playful memes of locals transporting their infirm or deceased loved ones on mules or donkeys have captured audiences’ attention. These memes served as a light-hearted commentary on the challenges posed by the region’s absence of roads.

Even as reporters may associate the prevalence of donkeys and mules with the state of economic neglect in the earthquake-stricken areas, they inadvertently miss how essential animals are for local residents to transport food and other necessities to places inaccessible to trucks and ambulances.

Some reporters used them to underscore the state’s neglect of the region or criticize the local authorities’ response to the situation of emergency. However, it’s worth noting that, similar to other regions across the globe, including the Himalayas and the mountains of Peru, Italy and Greece, where donkeys and mules are relied upon for husbandry and local transportation, their significance cannot solely be a reflection of the degree of development or lack of access to modern amenities. These animals have been central to the very fabric of the local socioeconomic and cultural infrastructure in the High Atlas Mountains. Donkeys and mules are central on many levels. Even as reporters may associate their prevalence with the state of economic neglect in the earthquake-stricken areas, they inadvertently miss how essential animals are for local residents to transport food and other necessities to places inaccessible to trucks and ambulances.

Not everyone can afford to own a beast of burden. Even if you do own one, there is an important distinction between donkeys and mules. During my formative years in Morocco, living in Lamhamid — a small oasis at the foot of the Anti-Atlas — my father owned several donkeys over the years. However, the event of owning a mule marks a social shift. It’s a remarkable feat. My father’s brown mule was no ordinary achievement; it was a monumental triumph that resonated deeply within our family and especially for my father. It was an indication of upward mobility. While some demonstrate their success by buying cars, others can show up by buying a beautiful mule. The underlying structure of the two is a sense of social promotion. [Mules are prized because they are larger, stronger and faster than donkeys, though it is said that donkeys are smarter. ED]

During the pre-independence period, my parents’ generation relied on camels, donkeys and mules as the only means of transportation in this arid and difficult environment. My conversations with my father about history over the years revealed that donkeys and mules were not just part of what he shared with me but also co-constitutive of the stories he told. My father forged a profound connection with these steadfast animals, and my brothers and I learned to tend to their needs. It was our duty to take care of them. Our daily chores included feeding our cherished donkey and, subsequently, the mule, providing them with meager rations of barley or hay before we sat down to have dinner.

These animals also had seasonal duties that they discharged superbly. Following the annual harvest of barley and wheat and the arrival of the summer, the threshing season was the season of the donkey par excellence. A group of donkeys and mules are strung together with a rope around their necks to form an interconnected walk that is then used to trod on the dry stalks in order to separate the grain from the hay. Rwa (threshing) took place in the summer in “anrarn” or “nwadar,” and this was an occasion in which donkeys and mules proved their mettle.

Over the years, the inexorable march of globalization introduced an array of modern transportation options, including bicycles, motorcycles, trucks, cars, and Chinese tricycles, which gradually supplanted the role of the donkey. In a conversation with my brother this past June, I inquired about the current population of donkeys in our village, and he lamented that their numbers had dwindled to fewer than ten, predominantly in the care of newcomers from distant regions who had since settled in our hamlet.

The news reports of the 6.8 earthquake in Adassil reminded me of the donkey. For those of us who are intimately acquainted with the High Atlas Mountains’ geography, the sight of mules and donkeys is a familiar occurrence and an expected one at that. These animals have been part of the landscape for hundreds of years, and their absence rather than their presence would be the event. When I visited my brother in Tahanaout at the foot of the mountains in the early 1990s, it was normal to see donkeys in local weekly markets. In the summer of 1994, I hiked throughout the region and witnessed closely how donkeys and mules carted food, wood, and animals. Even before the circulation of the pictures of the donkey serving as an ambulance during the earthquake, families used these beasts of burden to transport sick people from areas with unpaved roads to health centers or to places where they could catch a taxi that would then take them to Marrakesh or Taroudant. What the world saw during the earthquake is a reflection of a socioeconomic reality into which these animals are structurally integrated.

In these rugged mountains, mules hold a cherished place within the hearts of the locals. In an era when automobiles dominate the developing nations of the 21st century, mules and donkeys remain irreplaceable assets, particularly in what remains terrace agriculture. The harvest yields are shared between the donkey and its custodian throughout the winter, a symbiotic partnership that ensures both are well-prepared for the challenges posed by the snowy and rainy days. While the donkey works hard throughout the year, the family really understands that the animal is its feet in these very isolated areas. Consequently, it is equally important for families to feed their children as their animals.

Within the High Atlas Mountains, Amazigh communities have weathered the harsh environment through the strength of familial and communal bonds. Simultaneously, they have adeptly adapted to the changing dynamics of their mountainous surroundings, with donkeys and mules serving as indispensable companions, facilitating their traverse through the rugged terrain. Much like my father’s profound connection with his mule, which proved indispensable during the annual harvest of dates and henna, the dwellers of the High Atlas Mountains have fostered deep bonds with their own animal companions, fully aware that these loyal creatures will bear them and their belongings to the “state road.”

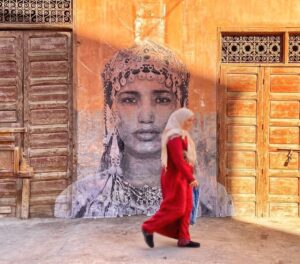

As agricultural activities dwindle and community members migrate to urban centers, like Marrakesh and Casablanca, in pursuit of alternative livelihoods, an increasing number of villagers in the High Atlas Mountains have found new opportunities through partnerships with tourism agencies. They now ferry provisions, water, and belongings for hikers, further cementing the enduring relevance of donkeys and mules in this region.

At the same time and with rising ecotourism, horses are now competing with donkeys and mules. In lodges, stables shelter crossbred Barb-Arabians. Horse-riding is introduced to expand the set of activities as tourists discover Amazigh villages through narrow rocky paths.

In Lamhamid, my native Anti-Atlas village, the role of donkeys in local economies is on the precipice of vanishing as Chinese tricycles are increasingly becoming the main means of transportation. Across countless villages in towering peaks of the High Atlas Mountains, however, donkeys and mules remain cherished possessions; their existence is a motor of the ecological tapestry that defines this majestic mountainous expanse. Even the Moroccan army and Gendarmerie Royale have special units dedicated to the use of mules to access remote areas in times of crisis. Although the seismic devastation in the High Atlas has limited their use, the existence of these units sheds light on the importance of the roles that donkeys and mules are called upon to play.

Because drought is transforming this region’s economy dramatically, I wonder if mules and donkeys still have a future in the High Atlas. As job opportunities decrease with a shortage of irrigation water for agriculture suitable mostly for man-made terraces, young people have flocked over the years to the city in search of work to support their aging parents and families. Only women, children, and elders populate most villages most of the year, awaiting the return of their migrant relatives during religious holidays. This puts a burden on women to raise their children and care for the elders. While historically men who practiced seasonal local farming managed household economies, including donkeys and mules, one wonders if women will add the burden of going up and down the steep valleys for the local weekly markets.

In my village, the women who remained largely do not have to worry about who should take care of the the donkey and the mule because the Chinese tricycle has filled this gap, despite its suffocating pollution. In the High Atlas, where the very terrain requires it and will therefore prolong the reliance on donkeys and mules, families do not have a choice but to continue hanging on to their animals. The loss of these traditions will signal the end of Amazigh settlement in the historical center of the Almohads, but also the disappearance of the mule and the donkey, unless mountain tourism includes these animals in its broader ecological approach.

As for the nagging question about my favorite animal I finally gave in: A Pepper, or fulfula as my daughter calls her, a mini-Aussie doodle, has recently joined the family. I wonder if my father would ever understand that my wife and our daughter see their dog in the same way the people of the High Atlas Mountains perceive their donkeys and mules.

Great article. This professor at UCLA, an Amazigh from Morocco, has explained a vital bridge between western and indigenous societies…donkeys and mules. And how for better or worse, the Chinese tricycle is replacing them. Can tourism replace traditional agriculture for survival in the High Atlas mountains? I sure don’t know but I’d love to go and see for myself. Aywa!! And the video clip, with no narrative voice, but with Amazigh speakers and smiling, dynamic female and male soldiers, and donkeys and mules, shows us how it is done sur le terrain…harsh and rough but full of love and respect, echtiram. Bravo TMR.

Bonjour, nous sommes une communauté de muletiers français qui desirons sortir les mules de l’oublie en France, Mule Qui Peut.

Nous avons un site sur lequel nous avons posté un article ou vous etes cités, bouton pour aller plus loin

https://www.mulequipeut.com/post/les-mules-au-maroc

Cordialement

Thank you from Mt ,USA .I am a horse and mule owner .