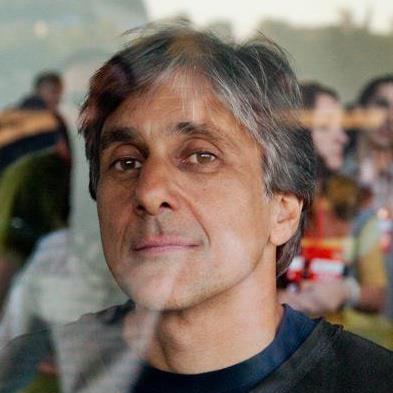

Ara Oshagan

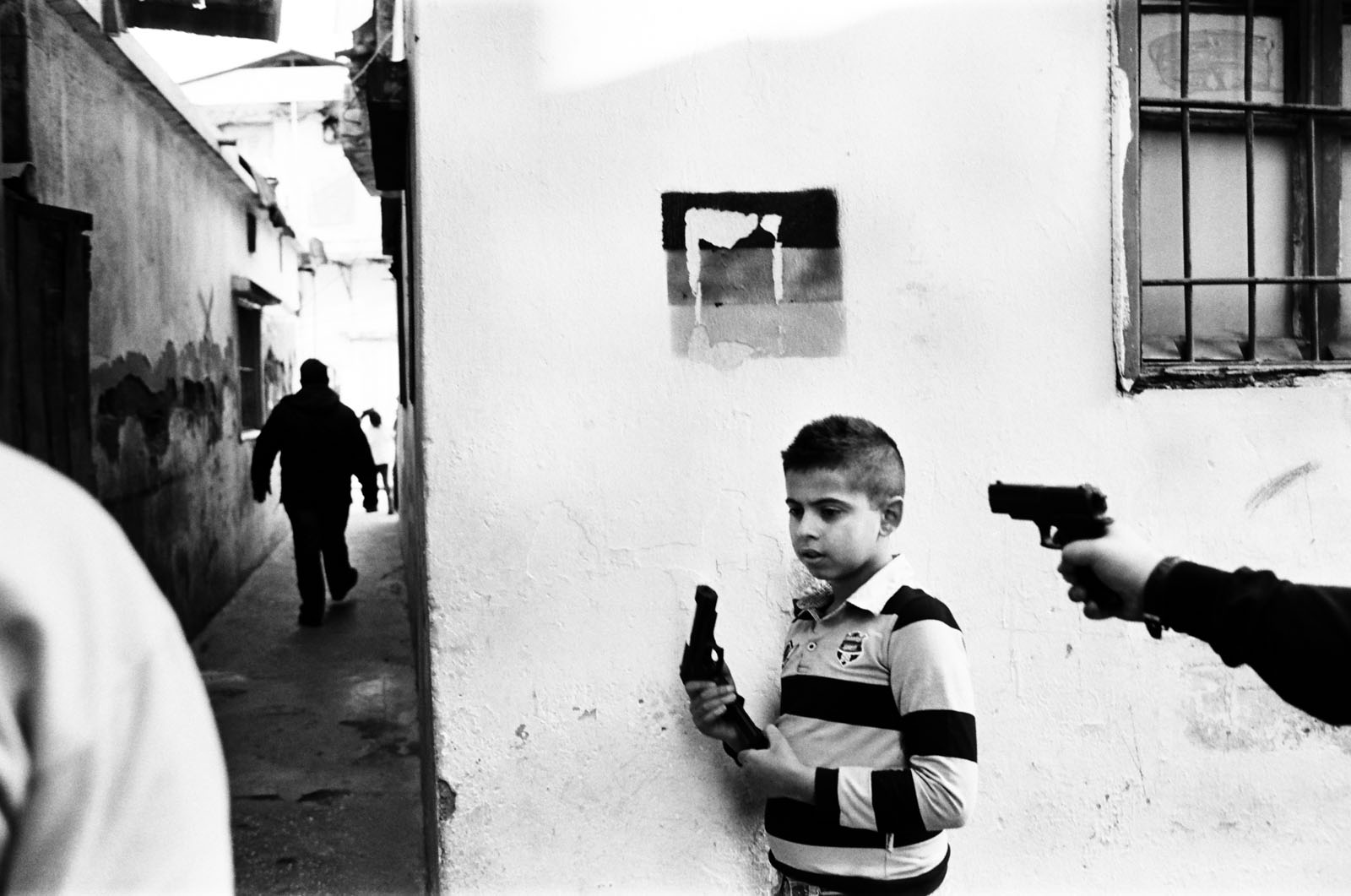

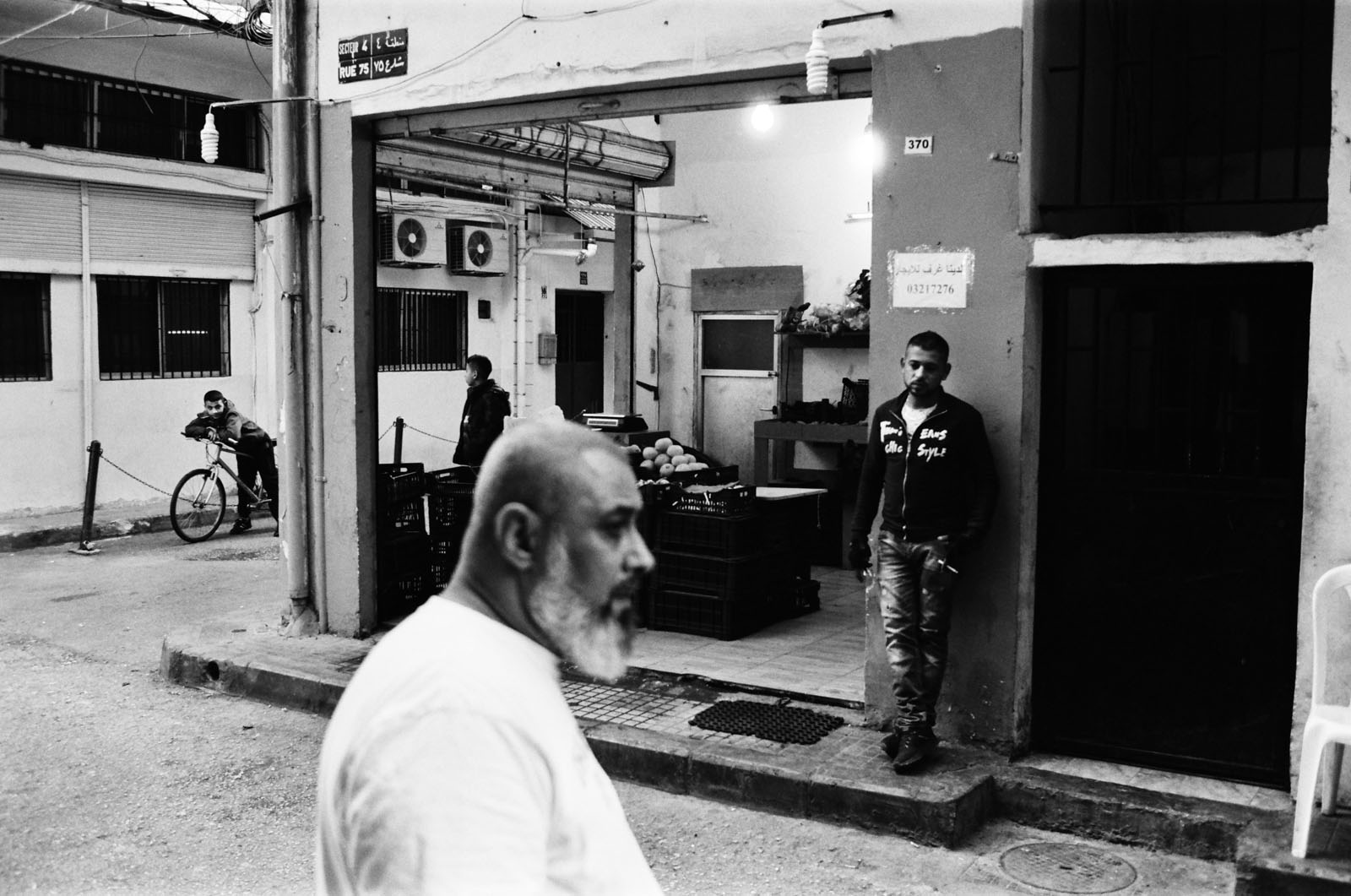

I am walking along the narrow and labyrinthine Armenian neighborhoods of Bourj Hammoud in Beirut—spaces with names like Nor (new) Marash, Nor Sis, Nor Yozgat. These are the namesakes of towns that hearken back to a distant past, to places and lands from which these communities, my communities were exiled by genocide. My friends who live in Nor Marash still call themselves Marashtsi (from Marash), even though the last time any of us, our parents or grandparents saw Marash, was 105 years ago.

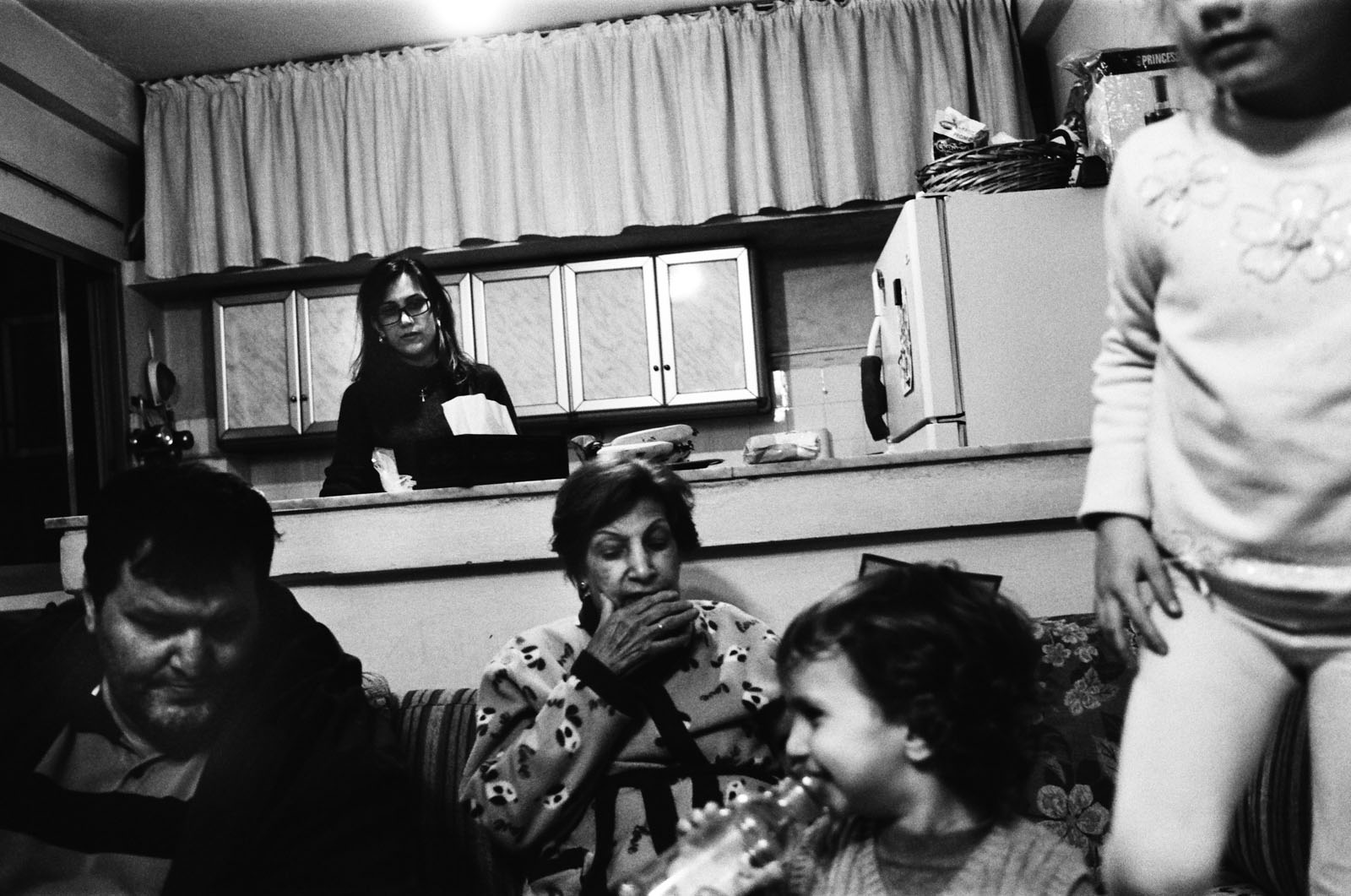

Nor Marash is a few intense urban blocks of concrete, electric wire and rush of life. It was originally settled by the same refugee families who were pushed to the brink of extinction by genocide. They re-started their lives and families in Beirut, Aleppo and other Levantine cities.

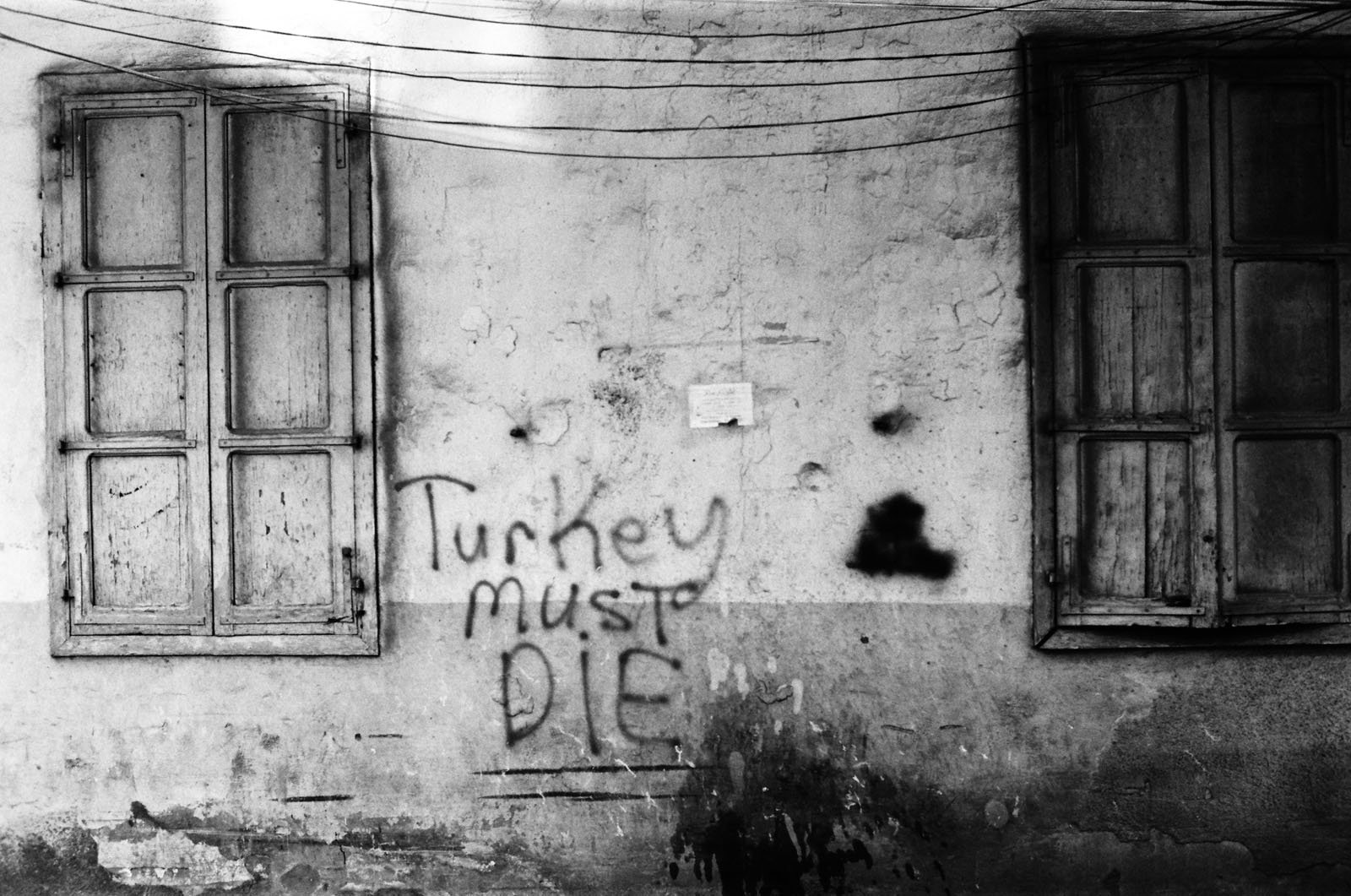

My friends in Beirut and I were born into these and nearby communities and grew up in families and spaces fraught with the collective memory of extreme violence and dislocation. Such internalized histories of dispossession persist. Across geographies. Across generations. They remain under your skin. They do not leave you in peace.

I was born in the American University of Beirut hospital — to Armenians parents, who despite nearly 30 years in an Arab country, hardly spoke the language at all. As a child, I knew Armenian and French better than Arabic. We looked back in time more than over the fence to our neighbors. We lived in suspension.

At the first sign of trouble, in 1975, we fled to the States, eventually to Los Angeles. A displacement that also accompanied a dissolution: my parents separated, and our family scattered. I carried one diaspora into another, along a fault-line of disruption and dislocation. I live in hyperdiaspora and as a result, own multiple histories. My identity is fluid and shapeshifts between Armenian, American, Lebanese, always unmoored, othered, ambiguous. My identity is a process — in harmony and contradiction, simultaneously.

Beirut has always occupied the spaces on the edges of my consciousness, always a presence. Now, 40 years later, I have returned to photograph.

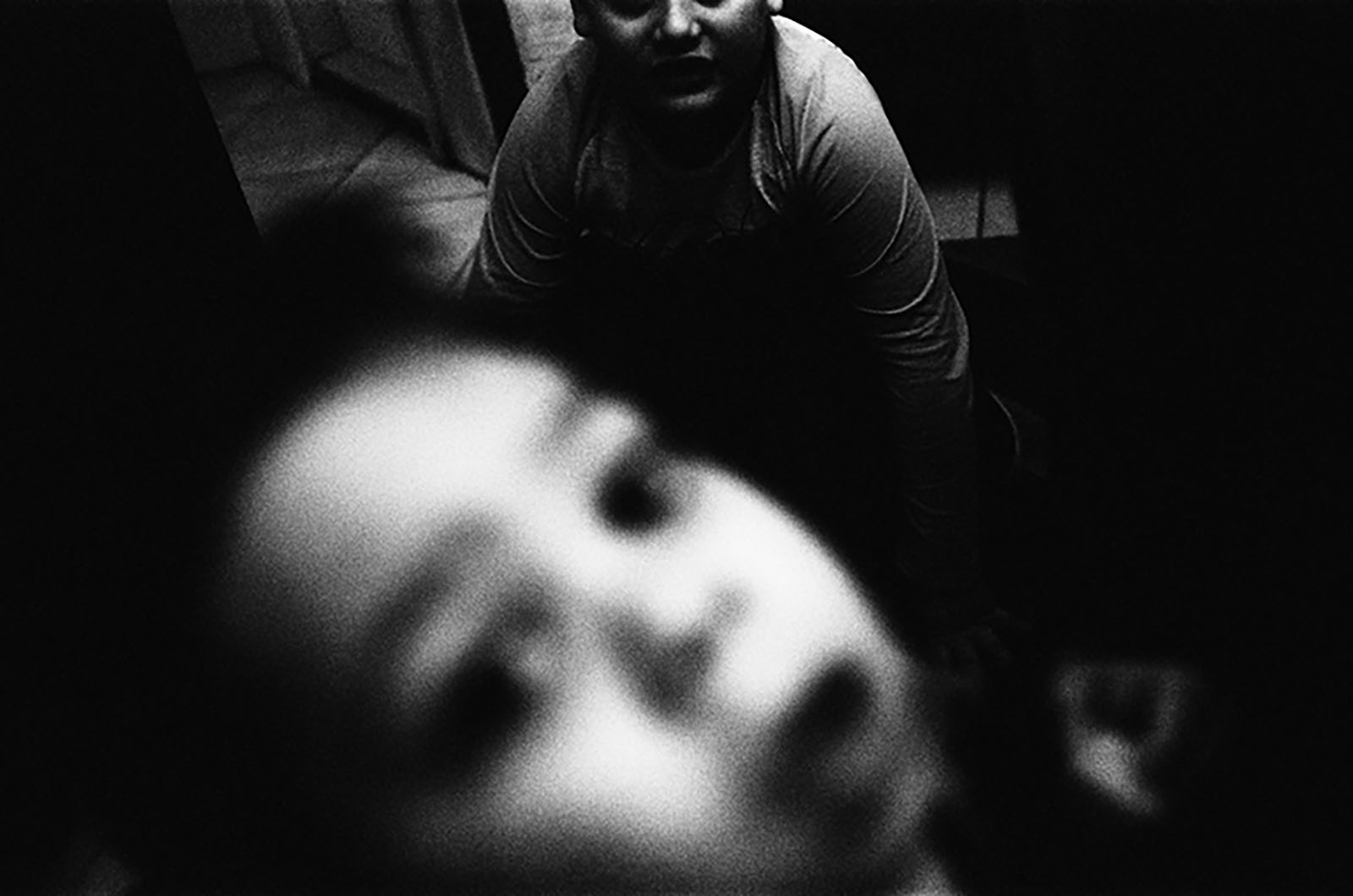

I am in the mountains above Beirut. I am standing at a landing, a foyer, on the second floor of a stone-built house. Stone tiles and four doors keep watch over this deserted space, silent and cold. Here I spent my summers as a child. And here, now, 40 years later, on this same tiled landing, I am overwhelmed: in this deserted space, among the silence of the tiles, I see myself: a past and a present, intertwined, interrupted, torn, inseparable.

I remember: I am child and I am running. Through woods, among dark thin trees, scattered pine cones; I am climbing, picking berries from oversize berry shrubs, clearing pathways of thorns, riding bikes on dirt, over hills, into rocks. I am running, always running.

I am running on pavement now with my best friend at my heels — we have fled school at lunch and are running downtown to find our favorite comic books; we are running past gardens with worn fences, strewn garbage, chaos of cars, past the street hawkers, shoe salesmen, nail salons, men in neat suits and women in purple hats, past cinemas, restaurants; we are running, breathless and oblivious to the violence brewing all around us about to engulf the city.

Now we are running as a family, in a taxi, speeding: my father tells us to get on the floor, we hear gunshots; we are careening down a deserted highway at ungodly speeds towards the airport.

I have returned to Beirut to look for what? A beginning? An end? What possible narrative? I peer down an abyss of time deepened by war, I bring with me the ruins of a family, a gulf within the self. The civil war has created a new city yet it seems nothing has changed.

I see: narrow chaotic neighborhoods falling apart, crippled by generations of violence, external and internal; the rush of life, stench of kebab and trash, noise, dirt, wafting music and laughter. I see men, women, children, ghosts at once familiar and utterly foreign; a community, breathing and vibrant, defiant; a place, an incessant undying past.

I see: a community still absorbing cascading wars, economic collapse and disasters, still connected to their far-off homelands of Western Armenia.

I hear: a melodious resonant language—my own Western Armenian, a language on its death bed, trying to reach across an even greater abyss to its beginning; and an invisible subterranean violence that can rise like a typhoon at any moment.

I see myself.

I try to articulate a response to this space, my space and community through which I move, talk, eat, curse its history and marvel at its resilience and life, lived as if there is no tomorrow. I try to find a narrative. Or perhaps an end.

displaced [sic] the book, by photographer Ara Oshagan and author Krikor Beledian will be published by art/photography publishers Kehrer Verlag in Germany, Fall 2021. displaced is Oshagan’s third work in a diasporic trilogy that begins in Los Angeles, travels to Armenia/Karabagh and culminates in Beirut.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)