While, as human beings, we are bound to never fully transcend our human-centered perspective, art offers a means to glimpse beyond our own biases and limitations, imagining a world where animals and humans interact on equal terms.

Pescara, Italy, 1975. It was the opening of Gino De Dominicis’ latest show at Lucrezia De Domizio’s gallery, yet visitors were barred from entering. As art enthusiasts clustered around the entrance, their curiosity was heightened by sounds and glimpses of movement. Peering inside, they saw unexpected forms — first a goose, then a donkey, an ox, some hens. This unusual gathering of animals was central to a work that excluded human spectators entirely.

Titled Exhibition for Animals Only, the show was dedicated to a non-human audience, animals observing each other, humans kept outside. The concept fit neatly within De Dominicis’ ongoing meditation on death, a recurring motif in his work, and here reflected the artist’s perspective on animals as beings blissfully unaware of mortality.

Through the exclusion of human visitors, De Dominicis also made a statement about the nature of art itself, posing the question: does art need human spectatorship to be art? The work was meant to subvert expectations and reframe the gallery as a space not simply dedicated to an aesthetic experience, but rather apt to rethinking the boundaries of perception and purpose of art itself.

The irony and sense of absurd in De Dominicis’ work taps into a longstanding artistic fascination with animals, particularly in contemporary art. Animals have served artists as allegorical or symbolic figures for centuries, often representing various aspects of human nature as both noble and flawed. However, in most representations, animals are seen through an anthropomorphic lens, reduced to metaphors for human characteristics. They are rarely seen simply as themselves, and in gallery settings, they are often reduced to props, mere objects in the spectacle of human spectatorship. In other words, the gallery as a zoo.

As De Dominicis’ show reminds us, this treatment of animals raises questions not only about art but about the ethics and power dynamics in the human-animal relationship itself. Where do animals stand in this equation — are they symbols, actors, or something altogether different? And what does it say about humanity that animals are so often pulled into these human-centered artistic conversations, silent witnesses to our own struggles and contradictions?

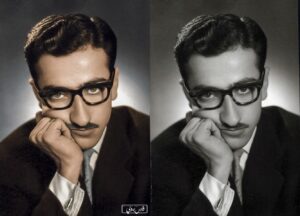

Khaled Hafez: human-animal dichotomy

Take Egyptian artist Khaled Hafez for example. In his canvases, animals are potent symbols, specifically of human behaviors, drawn from a unique intersection of myth and modernity. In his work, animals function not as passive props but as lively embodiments of the many cultural and social contradictions that shape contemporary Egyptian life.

Hafez explores this human-animal dichotomy through a range of overlapping tensions: Middle Eastern versus Western cultures, sacred versus commercial, and, crucially, male versus female. Hafez’s visual language draws from both ancient Egyptian gods — divine beings who often possessed animal traits — and contemporary superheroes, whose powers frequently originate from connections to animals, like a spider or bat.

The god and the superhero possess a duality, both embodying human and animal traits. Through these figures, Hafez’s work suggests a symbolic fusion, where these dichotomies don’t cancel each other out but rather combine in complex, singular forms.

Rendered in scroll-like or pixelated compositions, Hafez’s paintings mix elements from media and advertising with the aesthetics of ancient Egyptian art. He reinterprets familiar images, overlaying them with cultural archetypes, creating a space where past and present intermingle.

Goddesses often appear as symbols of female supremacy in his works, positioned against smaller male figures, challenging Egypt’s prevalent sexism. This placement of figures carries an implicit critique of dominant gender biases in Egyptian society, questioning longstanding cultural roles.

Meanwhile, Hafez’s depictions of animals, particularly bulls, cows, and horses, embody a specific political symbolism. In works created before the January 25 Revolution, animals and human figures — military and civilian — share the same space in scenes charged with tension. Once again, in a series of paintings, animals reflect not only human characteristics but also the inherent contradictions of societal conflict, as if they too are embroiled in the intense, fractured political landscape.

Wael Shawky: political symbols

Wael Shawky, another prominent Egyptian artist who represented his country at the Venice Biennale this year, approaches the use of animals with even more overt political lens, though his work maintains a similar tension between history and myth to Hafez. His 45-minute video “Drama 1882” was described as “mesmerizing” by a New York Times art critic observing visitors to the Biennale’s Egyptian Pavilion.

Shawky’s Cabaret Crusades series is a three-part adaptation of Amin Maalouf’s historical study The Crusades through Arab Eyes (1984). In the work the artist reimagined the events of the Crusades, using puppet figures to depict the conflicts in ways that challenge traditional western narratives.

In Shawky’s hands, the Crusades unfold through 110 marionettes with animalistic qualities, distancing the viewer from human characters and thus allowing a more detached reflection on historical events. Also for Shawky, like for Hafez, animal figures symbolize the blending of Eastern and Western identities, a cultural hybridity that goes beyond mere physical appearance. In Shawky’s hands, these figures take on an almost relic-like quality, reminiscent of ancient bestiaries cataloging the “Other” as a way of defining the self.

By turning to animals instead of humans, Shawky asks viewers to consider how cultures construct and distort the enemy “other” in the telling of history, an observation with significant implications for understanding modern East-West relations. For his solo at Lia Rumma Gallery in Naples in 2018, the artist explained to curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev how animals are connected to the land in his work: “Drawing is never something I can foresee. It can become an animal connected to a city, for example. What I want from the work is that in the end it is sufficiently precise in its details that one could no longer criticize the individual parts, because it seems to really exist, somewhere. The landscape, the shape is there, a four-legged animal.”

Through the different mediums which compose the varying episodes of Cabaret Crusades, Shawky suggests that history is a shifting, complex narrative constructed through both myth and conflict, in which animals become messengers between worlds.

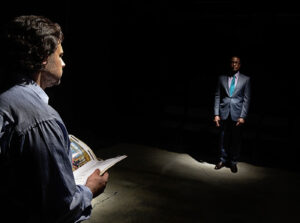

Walid Raad: weaponized animals

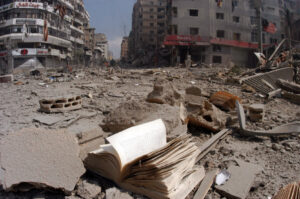

And speaking of conflict, we should remember that we have seen how animals in art can serve even darker functions, moving from symbols to active agents within human conflicts. Lebanese artist Walid Raad offers a pointed take on this theme in his fictitious historical project, The Atlas Group, which explores Lebanon’s war-torn recent past.

In the series of works We Have Never Been So Populated (described here in a video narrated by Raad himself) the artist imagines a right-wing Christian militia attempting to weaponize invasive bird species during the Lebanese wars. The militia’s goal was to release these birds into enemy territories to disrupt ecosystems.

Drawings of birds mingle reality and fictitious records of this operation, highlighting the absurdity of this “invasive bird strategy,” which ultimately failed after repeated attempts. Through this bizarre story, Raad draws attention to the ways in which animals can be co-opted into belligerent human endeavors, becoming unwilling participants in warfare.

His work ultimately underscores the unethical and foggy space that animals occupy in human conflicts, particularly when they become pawns in geopolitical games.

For his 2022 show at Paula Cooper Gallery in New York, where he presented the series, the artist said: “This show is about a series of strange encounters with peculiar objects and living beings: invasive birds used as military weapons; paintings of clouds that appear on the backs of other paintings; gold and silver cups that attract particular arthropods; and fickle waterfallsSuch fantastical encounters usually raise doubts about the sanity of the person witnessing and recounting them. Or, they may be viewed as symptoms of the ideological, economic, cultural, and historical traumas and forces that shape our world. But what if these encounters are ‘real,’ in the sense that they emerge in another realm, the one affixed to the imaginary?”

Damien Hirst: ethical issues

Perhaps the most notorious artist to involve animals in his work is Damien Hirst, whose provocative pieces have incited strong reactions, often centering on issues of cruelty and spectacle. In Hirst’s infamous work, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, a tiger shark suspended in formaldehyde has been at the center of ethical debates. Critics argue that Hirst’s pieces reduce animals to mere spectacles, with PETA and other animal rights groups condemning his work as exploitative. Yet, figures like Hans Ulrich Obrist laud Hirst’s work as emblematic of contemporary society’s uneasy relationship with death, suggesting that Hirst’s pieces reflect a deep-seated denial of mortality. Works like Heaven, another large shark in formaldehyde, and A Hundred Years, featuring a cow’s head slowly consumed by flies in a glass cube, confront viewers with the visceral reality of decay.

These works echo themes found in Baroque art, where violence and death were frequently displayed as memento mori, reminders of life’s fragility. In exhibitions such as BAROCK at the MADRE Museum, curators argue that these pieces presenting animals, however unsettling, serve as mirrors to a society that increasingly resists mortality and glorifies spectacle, much like the Baroque masters sought to capture the world’s contradictions and uncertainties through dramatic imagery.

Toward a new relationship with animals in art

Today, there is a significant shift in the way contemporary art approaches animals. Rather than positioning animals solely in relation to humans, a new trend encourages viewers to see the world from an animal’s perspective, a perspective that imagines a world in which humans are not the primary focus.

This shift raises profound questions: Can art help us transcend anthropocentric views, allowing us to imagine new ways of existing alongside the animal and vegetal worlds, even with artificial intelligence as a potential participants?

At the recent Gwangju Biennale, curator Nicholas Bourriaud explores these questions in his main exhibition, proposing a reimagining of our relationship with animals and nature through the Korean concept of Pansori, a form of narrative music that emphasizes symbiosis between performer and audience, often invoking natural imagery.

Bourriaud, an art critic, and curator who has long addressed the Anthropocene, argues that art can foster a collective rethinking of humanity’s place within the natural world, urging us to shift away from a limited human perspective to one that values animals and plants — and increasingly, artificial intelligence — as integral parts of the planet.

“Above all art is a unique space, mental, social, and symbolic, that encompasses all others,” reads the Biennale press release. “It is a place where reality gets recomposed and questioned, where social life and space-time can be reinvented.”

While as human beings we are bound to never fully transcend our human-centered perspective, art offers a means to glimpse beyond our own biases and limitations, imagining a world where animals and humans interact on equal terms. Art in this context becomes an experiment in empathy, a platform for seeing through another’s eyes, even if that gaze may always be filtered through the human experience. For while the meaning of life, the universe, and everything might be “42” — at least according to Douglas Adams in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy — to a cat, the answer may simply be a simple meow. An enigma we might never unravel, but one worth pondering.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)