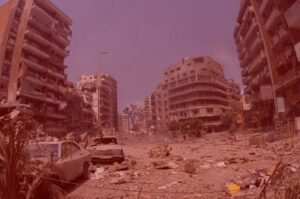

A few months ago, I watched Jocelyne Saab’s 1982 documentary Beirut, My City, filmed during the 1982 Israeli siege on Beirut. I was haunted by the beautiful and heartbreaking script written by Lebanese playwright, actor, and director Roger Assaf and decided to translate it from French to English. As I worked on my translation from California (where I had moved less than 3 years ago) and watched the news from Lebanon and Palestine, I began writing letters to Roger. I wrote to him because, tragically, it felt as if he had written his text today. I wrote to him because I felt he had seen it all. I wrote to him so that I don’t go insane.

July 30, 2024

Dear Roger,

I’m not sure whether to “it” or “she” the word war.

Here I am, translating you on the day Israel bombs Haret Hreik. I’ve been delaying this project, but today, the grief pulls me gently by the throbbing in my shoulder blade and leads me to your words.

Your words about the 1982 siege of Beirut resounded in a small dark cinema months ago. You wrote them in Paris, I heard them in Oakland, 42 years later. You wrote them in French, I write in English. Arabic haunts us both, so it is only unnatural and expected that, more than four decades apart, we are witnessing our people and their houses “elevated toward God in shrapnel,” as Adonis puts it in his poem “Time.” “How bitter now language is, how narrow the alphabet’s door,” he writes.

The word genocide, how to translate such terror, almost 300 days after?

August 1, 2024

Dear Roger,

Translating you, I give the war the pronoun it, and I consider giving Beirut the pronoun she.

I’m by the lake water, where the mountains speak mountain in the morning and blue shadow in the afternoon. This transformation, this dreamlike haze on the horizon, is caused by forest fires. Someone said there are eight or nine of them in California right now. California is always hills and highways. California is always smoke.

I didn’t call my parents yet for their analysis: do they think this will be a war like 2006 or worse? Instead, I stepped on a boat and was elevated at the end of a parasailing rope a thousand feet above South Lake Tahoe. I don’t know how to visualize a thousand feet, as I’m still not used to American ways of measuring distance or temperature. Or the absurd way Americans write the date — they’re always in such a hurry that they place the month before the day. As I soared above the blue-green-turquoise-teal colors of the water, I began to cry. How is it that the lake is a lake, that the mountain is a mountain amid such slaughter?

Someone on the boat, learning we were from Lebanon, said he had neighbors from Pakistan. I nodded. “Do you like California?” he asked, adding that his neighbor did. The problem with those who come where we come from is we trace a direct line between people’s ignorance and bloodshed, drones, torture.

Somehow, dear Roger, every two decades or so, I end up thinking about wars near bodies of water.

In 2006, M. and I escaped Lebanon by taxi. From the Mediterranean to the Dead Sea. My spine lifted by the too-much-saltness of it. We are always undrowning above something dead. It was the first time I pointed to Palestine across the water.

Sometimes I ask the water questions about love — how much until, how long before, how heavy, how tender.

In the evening, the saltless lake disappeared. I poured myself a glass of white wine and didn’t forget a thing.

One of your sentences that haunted me as I meandered out of that cinema was, ‘Nothing is more dangerous than a people that has perceived its desires.’ This is why protesters are crushed. This is why prisoners are tortured. This is why tents are scorched. This is why journalists are killed. This is why the imagination of children is murdered. This is why women who want to belong to themselves are terrifying.

August 3, 2024

Dear Roger,

I read your words out loud, and the lake’s waves respond. It’s a cloudy day here, cold and warm enough to sit on the sand. It’s almost 10 a.m., and you are saying something about memory. The waves are saying something about eternity. I realize there’s no such thing as being late. Last night, I was too late for something I now forget, but I looked up at the exact moment a star shot across the California sky, yellow tail and all, as if in an animated painting. It might have been a meteor. No matter. I wasn’t late. No one ever is. As for beauty, it’s always cruel.

You write about Kareem as the camera shows him alive among friends. You say his name resembles him and his brutal death doesn’t. I know what you mean because I’ve seen how people who believe their death will resemble them trust the world. They who have calendars. They who don’t fear a bomb when they hear a plane. They who think the death of the people of Gaza must resemble Palestinians. I don’t share graphic images of death from Gaza on social media because their death only resembles those who kill them. If I had to share something like their names, what would it be? A river? A swallow? A breeze?

Today is James Baldwin’s birthday. He wrote, “Love has never been a popular movement. And no one’s ever wanted, really, to be free.” He believed in love, not the kind marketed on Hollywood screens. Perhaps the kind we create as we make plays, as we watch tragedies in a burning city’s small theaters. The kind that has us reach for each other and beyond our fear as we wander out of those spaces.

The Haunting Reality of Beirut, My City

August 5, 2024

Dear Roger,

I couldn’t read your words yesterday. August 4 isn’t a day. It’s an eternity. We carry it with us across years. Across continents. Across our own forgetfulness. Even as we make coffee. Even as we laugh. Even as we fall in love. August isn’t a month. It’s a drowning. Perhaps we bite into a summer peach. Perhaps we scream. Or call a friend. Or cry. Perhaps we don’t even open our bedroom curtains. August 4 isn’t a past. It’s a haunting. Some of us lived. None of us survived.

By the afternoon, M. had convinced me to take a walk in the park. It’s strange for me — taking a walk in a park. Where we grew up, M. & I, there were barely any public parks. We walked by the Corniche, yes. Yesterday, we spoke of love, of time, of money, of returning. We the exiled long most for our homes when they are destroyed.

Today I decided to personify Beirut in my translation, giving her the pronoun she. In French and Arabic, Beirut is always she. You describe “her living body.” You describe being Jewish and Palestinian, Muslim and progressive, woman and leader, anarchist and organized. You describe the possibility of living beyond the fixed. The possibility of desire. But such desire is dangerous because it connects truthfully and dismantles deeply, and that is why Israel besieged Beirut in 1982, and that is why it is trying to exterminate Gazans in 2024. “The price of utopia,” as you call it. Try telling an American about being Jewish and Palestinian or Muslim and progressive. There is no language for vastness here. All here must be quantified and logical, all must be defined and sellable, all must be useful and conquerable. The American “dream” is steeped in a nauseating, bureaucratic realism. Cafés close too early. Every phone call begins with, “If this is an emergency, please hang up and dial 911.”

This morning, I read that Israeli jets broke the sound barrier over Beirut. I called my mother, who is convinced an all-out war isn’t coming. Every day, I call my friends and we laugh at our political analyses, our certainties, our absurdities, the way we reason, “There’s no element of surprise” or “The Israelis can’t afford this.”

Roger, what made you fall in love with theater? With Beirut?

August 7, 2024

Dear Roger,

I can only hour-by-hour my days. Every morning, M. reminds me of my antidepressants. My daughters remind me I have a body.

I can only paragraph-by-paragraph your text. Its heartbeat echoes, “Desire, Memory, Image.” In that dark cinema in Oakland, I was especially possessed by the word “desire.” Isn’t it what stirs memory and image? My favorite lines by poet Stanley Kunitz are, “What makes the engine go? / Desire, desire, desire.” What else is there?

Last night, M. and I wandered down a street in Berkeley, as he wondered, “If we keep going down this way, won’t we reach the sea?” “I have a feeling the sea is right over there,” he repeated, pointing at our desire for the Mediterranean. There is no sea near Berkeley; there’s a bay somewhere, and it wasn’t down that street. Still, we walked, kept walking toward our memory. In California, we recalled our invented image of Beirut, the city on the hills whose streets undoubtedly led us to the Mediterranean.

One of your sentences that haunted me as I meandered out of that cinema was, “Nothing is more dangerous than a people that has perceived its desires.” This is why protesters are crushed. This is why prisoners are tortured. This is why tents are scorched. This is why journalists are killed. This is why the imagination of children is murdered. This is why women who want to belong to themselves are terrifying.

August 8, 2024

Dear Roger,

I’ve been writing about mountains and death, so when a literary magazine asked me for a poem, I sent one about sex and calla lilies (Lazarus flowers I learned about here, in California). As for Darwish, he wrote of coffee and dreams and water in his book about the siege you describe. “Is it August?” he asks, “Yes, it’s August. And the war has become a siege.” T.S. Eliot was wrong about April. It’s undoubtedly August which is the cruelest month, “mixing memory and desire.”

In almost-April, swimming with F., I asked her, “Wouldn’t it be beautiful if I died in July, or the birthday month of a beloved?” Without a second of doubt, she replied, “Yes,” and dove smiling into the clear, salty water. We were both thinking about old souls and bridges.

In April, M. and I stared at a distant battleship in the Pacific Ocean and instantly remembered the July 2006 war. Water, for those who come where we come from, is never just water. Balconies aren’t merely balconies.

I was gifted Darwish’s Memory for Forgetfulness on the same day I listened to your words, Roger. My friend, returning from Lebanon, gave me the Arabic book in that Oakland cinema. Every time I open it, I smell the pages. Don’t you love the scent of old books? It carries me to a rainy afternoon in Tripoli, on a balcony perhaps, in September probably. Or perhaps toward dark streets where my friends and I laughed — something against clocks and dotted lines.

I couldn’t translate much today. Words were too heavy. I began with “the ruins” and ended with “voyeurism.” There were words I knew but still had to look up on Google Translate, as if this would undo them: crânes/skulls, éventrés/disemboweled, consciences/consciences. In French, I confused “ce qui passait pour être,” “what seemed to be,” with “ce qui passait,” “what was happening,” because I was trying to read faster than my grief and less painfully than nuance. In my translation, I omitted the expression “almost immediate.”

Sometimes what happens is too much for a foreign language. Sometimes the almost immediate is impossible in a foreign time zone.

August 10, 2024

Dear Roger,

This morning, I woke up with a headache and read the news of the al-Tabin school massacre: Israel bombed the dawn prayer. So many school bombings in the past months that I’ve come to associate the word “school” with “massacre.”

“Prayer is better than sleep,” goes the call. I caught myself hoping whoever was severely injured would die quickly, sleep eternally. Death is better than life.

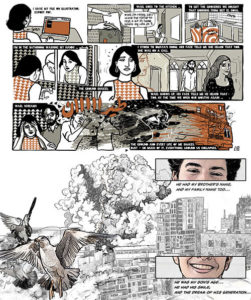

I translate your words about the carnage of Sabra and Chatila, more than 300 days into daily Sabras and Chatilas. In 1982, you wrote that Israeli torture is reported but not seen because the world is unable, or perhaps refuses to look directly at such horror. The world can only take “tolerable doses of voyeurism.” Today, the horror is both reported and seen. Body parts and the screams of the burnt-alive flash from our phones, and world powers remain complicit. As for us, we try to remind ourselves of the meaning of words like genocide and massacre. Of the meaning of water. Of the meaning of love.

Decades ago, I watched your rendition of Waiting for Godot at Beirut Theater in Ein el-Mraysseh. It was 2003. Three years after the liberation of southern Lebanon and three years before the 2006 war. The most haunting element in it, for me, was a bare tree branch on stage. That’s how memory, image, and desire work. Godot, of course, never came.

Roland Barthes writes, in A Lover’s Discourse, “Am I in love? — yes, since I am waiting. […] The lover’s fatal identity is precisely this: I am the one who waits.”

I translated four of your sentences today. I thought I’d do more, since I’m alone at a friend’s house, here to water her plants while she’s away, here for some solitude, away from my family, here to escape. We are always escaping. All I could muster was four sentences. In Arabic, the word for sentence has a hint of togetherness. In English, a sentence is a group of words and a punishment. I was escaping. I scrolled through the news, made a mug of coffee, read, scrolled through the news, made another mug of coffee, spoke to a friend, watched funny reels, cried, ate some grapes and cheese, napped, talked to another friend, scrolled through the news, took a long walk, spotted little unripe green olives on branches, pet a dog that greeted me, and watched the sky bruise purple. I was waiting.

I’m now on my friend’s patio, and the houses on the hill opposite me, not noticeable during the day, light up like eyes. I stare back at them. I look up. There is a single star. The moon is an eyelid. I’m waiting. Here where my friend lives, and where most people don’t care about the extermination of Palestinians, stands Mount Tamalpais, Etel Adnan’s friend, about whom she wrote, “Do not climb that mountain unless you know it needs you.” I haven’t been to Mount Tam yet, though I’ve greeted it as I drove here. I live in the valley of Mount Diablo, in a place where most people don’t care about the extermination of Palestinians either, and I greet the mountain every time I see it with, “Hi, Diablo!” waving. My daughters think I’m strange. I think we should always greet the mountains, and the moon, and the first star, and the water, and the blood inside us. Like lovers, like Vladimir and Estragon, they wait. They have been waiting.

August 12, 2024

Dear Roger,

If I were writing in Arabic, I would have typed “the south” instead of “southern Lebanon.”

If I’d stayed in Beirut, I would have continued acting on stage. Perhaps Medea. Perhaps Medusa. Perhaps Heda Gabler. Perhaps a character from Saa’dallah Wannous, who reminds us, “We are sentenced to hope.” Perhaps one of the Sirens. Perhaps Orpheus, whose music defeats the Sirens and tenders the heart of Hades, but who, like a true poet, can’t help looking back.

If my parents had emigrated during the civil war, would I have become a better or worse translator?

If translation were truly possible, we would stop making theater, or poems, or love.

If the horses stranded in the south could speak, they would say, “We are standing in the middle of the road, lost, grieving. We have left the ruins in search of humans.”

If grief could speak, she would sigh, “I’ve been having so many nightmares lately. In one of them, I was running away from gigantic metal balls falling from the sky.”

If the sky could speak, she would pray, “Let me sleep. Please. Let me sleep.”

Last night, I looked up to watch the Perseids, which appear from the direction of the constellation Perseus. Perseus, who cut off Medusa’s head. So what if she had snakes for hair. So what if she turned men to stone. Perhaps she was slaughtered because she never looked away, never averted her gaze. I looked up and failed to forget. For meteors, we say shower. For blood, we say bath. For desire, we say surrender. For land, we say remember.

October 15, 2024

Dear Roger,

It’s been two months. It’s been assassinations and razed villages. It’s been thousands of dead. It’s been a moment, an eternity.

How many theaters have closed? How many cinemas deserted?

No one had predicted this, but then again, who ever does? We’ve only ever played war commentator to reassure ourselves, to tell ourselves kinder stories.

I want to believe you, dear Roger, when you write about the Israeli army’s strength and powerlessness. I want to believe Mourid Barghouti when he asks his enemies, “What makes you, at the height of your victory, afraid?”

Perhaps all months are the cruelest, even as they are months of first kisses and first rain.

I survive by looking for small tendernesses. Today, the tenderness was listening to Fairuz’s prova of “Kifak Inta” on vinyl. I prefer the word “prova” to “rehearsal.” Something about the only evidence being trial and repetition.

Fairuz speaks to Ziad, who starts singing, asking the lover how he is. Asking the lover about distance and children. About memory. Some words are best translated literally. Kifak Inta would literally translate to, “How are you, you?” The insistence of it. The bittersweet recognition. The humor.

Dear Roger, what’s the refrain?

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

A lovely French friend of ours returned to live next door in lovely Whitstable-by-the-sea, where Turner painted its blood-red sunsets. She introduced us to her new Israeli husband. Being v pro-Palestine, I didn’t wish to parley with him. Not really a problem as he was always stoned on cannabis which he grew in their greenhouse. He was virtually in a waking coma! My lovely French friend explained that he had been so traumatised by being an IDF soldier that he could no longer work as he was always a zombie. They soon divorced as she couldn’t get a job in Israel being a foreigner. I was glad.

Thank you for sharing the intimacy of this process. “I need to write to you so that I don’t lose my mind” is so relatable. That reaching out, to put a hand on something you understand, the way someone else made sense of nothing making sense. Also how translation can be paying respect, an exploration of connection – I am working with this, too.