Delusion and forgetting the present in the architecture along the corniche of Egypt’s historic port city.

On a rainy day, a pair of adolescents strolls downtown. The heavy rain and the grey winter sky, characteristic of Alexandria in January, create an ideal photo filter for a digital photograph. They pause along the corniche to capture a picture with a smartphone of the Little Venice, a grand residential structure that borrows its ornaments from Venetian architecture. This photograph is later shared on social media platforms with the caption “Beautiful Alexandria under the rain” and hashtags such as “heritage,” “cosmopolitan,” “golden days,” and “belle époque.” The image is widely circulated, shared, and reposted numerous times, ultimately leading to the creators being forgotten.

It is not uncommon to come across similar photos, potentially in black and white with added faux dirt effects that are shared with comparable captions. This may evoke the question of whether the photograph is old or recent.

Over the past ten years, Egypt has witnessed astonishing interest in possessing and circulating vintage photographs. A phenomenon that historian Lucie Ryzova refers to as “archive fever.” She has theorized that those liberated vintage photographs are freed from their historical contexts, meanings, and referents; and are too easy to re-signify.

The significant collection of vintage photographs, posters, and advertisements has fueled the sense of longing for a better past among the contemporary Egyptian population, to the extent of recreating vintage-like new distorted representations of reality.

Involuntary Memory or the Proust Effect

Back to our case of the two adolescents. One could argue that it was not a state of involuntary memories that motivated their nostalgic photograph. The term “involuntary memory” was coined by the 20th-century writer Marcel Proust. This phenomenon refers to memories that are triggered by a scent, a taste, or even a sound. Commonly known as the Proust effect, it describes the experience of sensations, which evoke childhood memories or bring back emotional experiences from the past.

To put it simply, Alexandria is a long, linear city that spans roughly 70 kilometers along the Mediterranean coast, running from east to west. As reported by the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS), the population of Alexandria is estimated to be 5,582,021 million residents. The city is divided into districts that sprawl east and west, resulting in a less densely populated downtown area compared to the rest of Alexandria. Each district is nearly self-sustaining due to the city’s elongated layout, possessing its own public services and facilities. It is likely that this young pair has matured and received their education with little to no ties to the city center. Based on my observations, a majority of Generation Z individuals start to explore and establish a connection with the historic neighborhoods of Alexandria, including downtown, when they begin their university studies. This is due to the fact that all public universities are located in and around downtown.

A Nostalgia That Is Not Theirs

According to architect Sophie Agisheva, in urban sociology, the perception of urban spaces, their representations, and production are heavily influenced by abstract feelings, emotions, and selective memories rather than realistic existence. To feel nostalgic for a place, it is necessary to first establish a physical connection with it, taking into account the factor of time. This raises the question: what memories prompted the nostalgic feelings that led the two adolescents to capture and take a photograph? What drove them to glamorize certain elements within the composition or the frame while obscuring the surrounding details?

The Little Venice itself, from my point of view, was a romanticized idea conceived by its owner and architect, an idea that served certain economic and political powers. Just as the Gulf countries provided opportunities for dreamers to pursue their aspirations since the 1970s, Egypt played a similar role in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Cairo, as the capital of the country overlooking the Suez Canal, and Alexandria, as the strategically located port on the southern Mediterranean coast, both served as pillars of support for individuals seeking to actualize their dreams.

During that era, Alexandria was a prosperous region that promised rapid success and prosperity. It served as a hub that drew people from within Egypt and beyond. No wonder residents from both Mediterranean shores found it convenient to reside, earn a living, acquire property, and establish roots. The city embraced individuals and groups regardless of their cultural and social backgrounds, providing a welcoming environment for those seeking refuge from uncertain futures in their homelands, and hoping to fulfill their aspirations in a neutral setting. European citizens, like many others, sought wealth and prosperity that seemed unattainable in Europe because of the political, social, and economic upheavals sweeping through their home countries at that time.

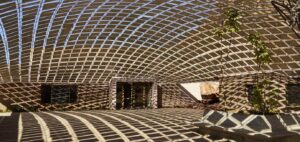

Acquiring a property along the first line of the reincarnated ancient Alexandria’s corniche was a feasible aspiration. Demonstrating affluence and influence through property ownership has long been inherent in human behavior. Alexandria, with its minimal intellectual and cultural constraints, allowed owners the freedom to construct as they desired, offering architects a canvas to envision their dreams.

In Europe during the 1920s, there was an increasing shift towards anti-romanticism in art, architecture, and literature. Designing in architectural styles associated with monarchy, feudalism, and religious authorities was no longer deemed acceptable. Writers and thinkers have spearheaded powerful intellectual philosophical movements that have impacted artists and architects. In turn, these creatives have played a significant role in shaping the collective taste of the public, including those with the financial means to drive and influence the market. In 1896, Luis Sullivan defied traditional architectural norms by constructing the revolutionary Guaranty Building, the early skyscraper in New York. Similarly, Walter Gropius introduced the Bauhaus style with his 1911 Fagus-Werk, which quickly gained popularity in Europe in the subsequent years, while in 1927 Alexandria produced a replica of Venetian Gothic architecture that was recently referred to as “The Little Venice.”

Both the proprietor and architect of Little Venice were yearning for a bygone era that was not their own. The nuisance of those sorts of buildings was defined by a nostalgic atmosphere that shaped Alexandria’s architectural landscape and urban fabric. It is even possible to hypothesize that the origins of nostalgia can be traced back to the early days of Alexandria’s creation. The architect and technical advisor of Alexander III of Macedonia, Dinocrates of Rhodes, implemented a Hippodamian grid plan for the city, merging ancient Greek urban planning techniques. This deliberate choice may have stemmed from a desire to recreate urban nostalgia for their homeland. The replication of Greece’s urban and architectural style, in a different environment and a foreign land, could be seen as an attempt to evoke and reconstruct nostalgic memories. The induced collective memories created by this artificial history add an interesting layer to the city’s design and perhaps its policing strategies. This lingering sense of nostalgia has become ingrained in the collective memory of the city. Persisting through the years, it is embedded in the Alexandrian DNA.

Engaging in almost daily flâneries through Alexandria, investigating its neighborhoods, streets, and Ruelles, which often bear French names as a nostalgic reflection, presents a challenge in maintaining a neutral and objective perspective as both an Alexandrian and an observer of the city. A state of duality, that I may as a researcher and artist succeed in hiding behind words and drawings. However, as an architect, it is not always the case. Most of the time I find myself forced to produce replicas of the past. After all, architects build according to the common culture, values, and wishes of their clients.

During my conversations and interviews, I have noticed a significant number of individuals expressing a deep sense of nostalgia. Many yearn for earlier times, particularly the Egypt of the 1990s, or earlier, in the ‘80s, ‘60s, and even the ‘50s, depending on their age. Surprisingly, the majority of individuals I have spoken to are not just nostalgic, but also melancholic, longing for the Kingdom of Egypt. They dream of the days of the abolished Paşas and Beys, the clean streets, and the idealized version of Egypt from that era. It seems to me that the fantasized image my conversation partners held of Royal Egypt was questionable, considering they were born long after the Kingdom’s downfall.

Modern Nostalgia

During the late 19th century, Egypt experienced significant national growth under the ambitious leadership of Mohamed Ali and his royal family, who ruled the country until the 1950s. The Egyptian monarchs sought education in European capitals, notably Paris, where they were inspired by what they observed. Eager to bring these conceptions of modernity to their own country, they endeavored to replicate European architectural and urban planning practices in Egypt’s capital and primary port city, Alexandria.

One can understand why they failed to comprehend the shift occurring in European societies towards modernity and a rejection of the turbulent past characterized by wars and conflicts. Their lack of exposure to Europe’s intellectual climate limited their understanding, resulting in a mere imitation of Europe’s historical artifacts. They not only managed to remodel parts of the Egyptian city to resemble a European counterpart but also actively promoted and exported this new image back to Europe. They urged European artists, travelers, writers, and photographers to spread the word about the transformed image of Europeanized Egypt. Their goal was to attract commerce and enhance the country’s diplomatic relations with Europe.

And no wonder, this image, managed to attract European individuals who were still dwelling in their past and unable to integrate into a society steeped in many capitalist, cultural, and political codes and movements. For those individuals who were enchanted by Orientalism, Egypt was viewed as the long-awaited paradise. In Alexandria, they could find everything they required — a city with a rich history, hospitable authorities, special privileges, and most importantly, the opportunity to cultivate their own sense of nostalgia.

By the second half of the 20th century, Egypt experienced political upheaval, leading to economic and social reforms. The monarchy was abolished and Egypt transitioned to a national republic. This shift also brought about changes in Egypt’s international diplomatic relations. Individuals who had previously enjoyed privileges during the former era lost their status, prompting many to leave the country within the following two decades.

During a challenging time when Egyptians were focused on rebuilding their new state, those who had left their hometown were feeling homesick. They sought to remember their past lives and share their stories. Family photos were being sent through mail to different parts of the world, memoirs were being written, and books were being published in multiple languages. Each person was recounting their own version of Alexandria, often romanticizing one aspect of the city’s reality.

Restructuring Memories

The nostalgic tale of the lost city, known as the golden age or lost cosmopolitan Alexandria, did not simply conclude there. Instead, it signaled the beginning of a new chapter in Alexandria’s history of nostalgia.

Let’s revisit the photograph of the Little Venice. The photographer made a subjective decision to emphasize a single aspect within the larger scene. That is what a photo does. Photographs are tools used by their creator to convey an intended message. The Little Venice photographer consciously or unconsciously ignored many details or realities. The photo for instance didn’t capture the challenge of navigating the muddy streets during rainfall, contradicting the caption that reads “Beautiful Alexandria under the rain.” Back in Alexandria in the early 20th century, it was the same situation. Literature and artistic expression often portray a skewed version of reality, focusing solely on the romanticized European Alexandria. The absence of voices representing the local perspective leaves a gap in understanding the true essence of life in the city’s impoverished areas. Without these authentic narratives, one is left with a limited and potentially misleading depiction of Alexandria’s diverse reality.

In the present day, more than a decade has passed since the 2011 revolt in Egypt. Another challenging period in the country’s social history is currently shaping its cultural narrative. Egyptians are facing myriad difficulties, turning the current era into a testing ground for various theories, making it hard to predict the future. Alexandria, as Egypt’s second city, is experiencing an exacerbated version of these challenges due to centralization. The city’s detachment from Cairo’s national market is leading to heightened economic and cultural stagnation. My friends in Cairo often tell me that Alexandria is a big village. Additionally, Alexandria is also facing looming environmental threats, and we choose to turn a blind eye to it. In such a turbulent environment, many seek stability through the familiar and comforting act of escapism — whether that means relocating to a different country or reminiscing about the past. This inclination towards seeking solace in nostalgia is now armed by vintage photographs and writings from those who departed Egypt post-1950s, in addition to their best medium: social media.

Should this be considered a third layer of nostalgia? A nostalgia for a future that is nostalgic for a better past, which was already a nostalgia for the older times of the city of nostalgia.