A review of the Booker Prize-nominated novel by Nadifa Mohamed based on the true story of a wrongly-convicted Somali in 1950s Cardiff.

The Fortune Men, a novel by Nadifa Mohamed

Penguin Random House 2021

ISBN 9780593534366

At the heart of two of British Somali author Nadifa Mohamed’s novels is a deep-seated admiration for her father and risk-taking Somalis like him, people who uprooted from their homelands to seek their own opportunities and survive despite the odds stacked high against them. In the author’s stunning debut novel, Black Mamba Boy (2010), her young protagonist’s journey from Aden to Somalia and then north through Djibouti, war-torn Eritrea and Sudan, to Egypt and then to the UK, was loosely inspired by her father’s own account of making it to Britain.

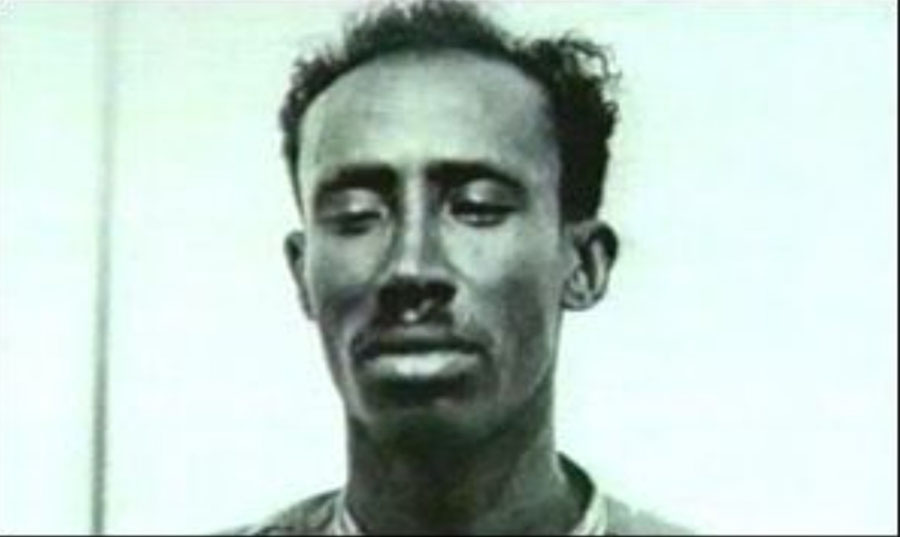

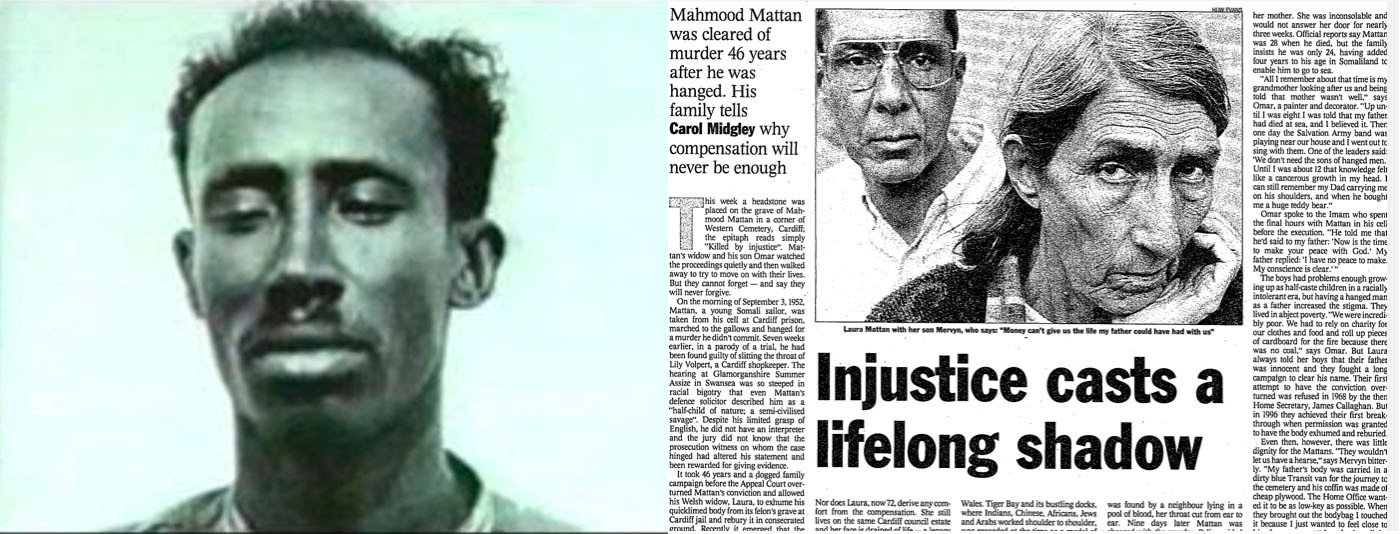

Mohamed’s latest and third narrative, The Fortune Men (longlisted for the 2021 Booker Prize, making her the first British Somali author on the Booker list), is based on the real life story of Mahmood Hussain Mattan, aka Moody — the last man to hang in Cardiff in the 1950s, after being wrongly convicted for the murder of Jewish shopkeeper and moneylender Lily Volpert (Violet Volacki in the novel).

Mohamed’s latest and third narrative, The Fortune Men (longlisted for the 2021 Booker Prize, making her the first British Somali author on the Booker list), is based on the real life story of Mahmood Hussain Mattan, aka Moody — the last man to hang in Cardiff in the 1950s, after being wrongly convicted for the murder of Jewish shopkeeper and moneylender Lily Volpert (Violet Volacki in the novel).

After coming across Mattan’s story in a newspaper article in 2004, Mohamed decided to further research the topic in hopes of creating a screenplay for a film. At the same time and while consulting with her father on the particulars of Somali life in Britain, she discovered that her father had very briefly known Mattan. They were born in the same city, and both were Somali sailors who’d arrived in Hull in 1947 before taking separate paths. In fact, in an interview with author Rabih Alameddine, the author revealed that it was while interviewing her father about Moody’s case that the details of her father’s life became so interesting that she ended up writing Black Mamba Boy first.

It would be another ten years before she’d return to the Mattan case, during which time, as though by a stroke of fate, the case files at the national archives had been opened to the public, allowing Mohamed insight into Mahmood’s entire jacket, from his first arrest all the way through to the preparations for his execution.

The novelist begins her story in Tiger Bay (now Butetown), Cardiff’s dockland district and Wales’ oldest multiethnic community at a time when it was still feeling the after-effects of WWII. King George IV had died and a young Elizabeth returned from her honeymoon to assume the throne. The Bay was the place “where you would find sailors carrying parrots or little monkeys in makeshift jackets to sell or keep as souvenirs … where you could have Chop Suey for lunch and Yemeni Salatah for dinner and find pretty girls with a grandparent from each continent,” where the entire community joined in the celebrations of the “Muslim Christmas” of Eid al Adha, and Kosher meat was “as good as halal religiously speaking.”

But Tiger Bay was also a sinister tough place to live “without money in your pocket,” where “they think a man stupid because he talks with an accent.” A place rife with street gamblers, half-caste children and prostitutes in tumbledown bars and where a mixed couple like Moody and his wife Laura Williams were denied State lodging, forced to settle for “black-walled, squalid places to rent,” ostracized by a community that treated her as a pariah woman, one “too stretched out for a decent white man.”

Mahmood Hussain Mattan was born in the year of famine in Qorkii, in British Somaliland. After a drought that lasted three years, followed by an outbreak of Rinderpest in livestock imported from Europe finishing off the family’s livestock and camels, his father turned to trade in Aden. Not long after, the family moved to Hergeisa where their financial situation improved considerably.

As with most Somalis, Moody’s family belonged to the apolitical Salihiyya order of Sufi Islam and as a highly respected member of the community, his father was asked to adjudicate religious cases. It isn’t until his father befriends the Haji, a character that might be based loosely on the order’s most renowned leader Muhammad Abdille Hassan (who transformed the order into a militant anti-colonial movement), that Moody decides that his father’s life is not one for him and he leaves to seek his fortune elsewhere. He ends up in South Africa where he joins the merchant navy and travels the world. He learns to speak four languages, before settling in Cardiff after falling in love with Laura. The couple had three children, David, Mervyn and Omar, but by the time of the murder they had amicably separated and lived in separate houses in the same street.

We don’t get much detail about Laura’s life, except for the snippets we learn from her conversations with Moody. However, it serves well to note at this point that although this part of the novel offers interesting background details into Moody’s early childhood and young family life in Somaliland at a time when the British and Italian powers were seeking fame and fortune in Africa through military expeditions, between 1900 and 1920, the actual details are, by the author’s own admission, mostly imagined and refashioned accounts due to the scant information available. However, born in Hergeisa, the author combines her knowledge of the place along with her father’s, writing of accurate historical events and cultural myths and practices, to give us a distinct and vibrant blend of history and fiction regarding the prevalent sensibilities in Somaliland in the decades preceding Moody’s departure. The novel offers insight into the wearying effects of racism on the minds and bodies of the colonized.

Throughout most of The Fortune Men, Moody is in jail, and so it is through flashbacks, conversations with Laura who visits him regularly in jail with the children, and interviews with the prison doctor and the lawyers as well as the full transcript of the trial, that the different layers of Moody’s character materialize and we discover a dapper, if complex and often times dislikable man with a temper, who stole money from the mosque, was estranged from the Muslim community who regarded him an apostate, and used Laura’s body to “avenge himself of every laugh, ‘nigger’, and slammed door.”

Moody was a man who in the Law Courts of “Bilad-al-Welsh” felt the blows of the racist lying community and biased judiciary system “like a man shot with arrows,” blind to his manifestations as “the tireless stoker, the poker shark, the elegant wanderer, the love-starved husband and the soft-hearted father.” We also encounter a defiant character who contrary to his folk in the 1940s and 50s, was very vocal about his contempt for the police, defiant in the face of their bigotry and racism, making him a known figure to the police which may have put him at a disadvantage from the beginning as “a wild savage needing the chastening of the law,” well placed to pin a murder on. In his closing speech, Mattan’s own lawyer described his client as “half-child of nature, half semi-civilised savage” — comments that may have prejudiced the jury and undermined Mattan’s defence. Further, what is shocking is that during the trial, the prosecution was not obliged to share their evidence with the defense.

Looking back on his life a few days before the execution, Moody laments that his children will one day hear that “he was a nomad, a chancer, a fighter, a rebel, but not from him, and therefore they will know the price of being all that, the potion and the poison taken together.”

What emerges towards the end of the book are the indisputable connections between Britain’s history of colonialism in Africa and a confrontation with a heritage of brutality. It is only with the arrival of British dominance in Africa that the death penalty came into existence. This was a form of punishment unheard of in Somali culture, in which communities lived by a form of mediation or reparative justice system, headed by the elderly devout members of the community that would adjudicate on settling feuds between warring individuals or tribes. “If only I could set fire to all your walls,” Mahmood comments on the miscarriage of justice that haunts the entire novel when all appeals to overturn his conviction have been exhausted, and he and readers have arrived at the point they both foresaw yet remained helpless to change: “I would burn this prison down and let everyone go free, whatever their crime, no one should steal their freedom. Somalis have got the right idea, you wrong someone and you’re forced to look over your shoulder for the rest of your life unless you make amends. You deal with each other face to face. Only cowards live by prisons and cold hangings.”

Mattan was executed in 1952, six months after the murder. He was denied the presence of any family member or acquaintance. His conviction was quashed 45 years later, on the 24th of February, 1998 — being the first case to be referred to the Court of Appeal by the newly formed Criminal Cases Review Commission. The family purportedly received a £1.4m pay out in compensation. In 1996 the family was given permission to have Mattan’s body exhumed and moved from a felon’s grave at the prison to be buried in consecrated ground in a Cardiff cemetery.

The epitaph on his tombstone reads: “KILLED BY INJUSTICE.”