Mohammad Rabie performs a searing self-examination, looking back on a lifetime of fear from early childhood to adulthood and at all the ways it has shaped his life.

Mohammad Rabie

Translated from the Arabic by Lina Mounzer

I remember very well the first time I experienced fear. I was about five years old. I was in a store with my father, talking to him about something I can’t remember anymore. I was little, and he was so tall that all I could see was his thigh right next to me. I was holding his hand, waiting for something, then I let go his hand for a bit before grabbing it again. Some minutes later, I realized I was holding someone else’s hand, the hand of a stranger, who led me out of the store and stood with me on the sidewalk. And then shortly after that my father appeared and took my hand again and we left the store. I said something to him but heard no reply, and when I looked up his face was hard and grim. I kept talking to him but he still wouldn’t answer, no matter how many questions I asked. We walked all the way home like this. When we entered the house, he exploded in anger, I’d never seen him like that before. He towered over me, his face right in my face, screaming furiously. My back was against the front door; I couldn’t move or escape. I was paralyzed by fear. My mother stood behind him, crying. I cried too. I can’t remember if he hit me but he must have. I couldn’t hold myself any longer and peed my pants against my will, shame mixing into the fear. I’d learned how to use the toilet a while ago, and had stopped wetting the bed like a little kid. I no longer remember today how that long-ago incident ended, but I remember exactly everything that happened before that sudden accident: my father’s enraged face, his bulging eyes, his open mouth and his screaming, words I couldn’t understand.

This was the first home I lived in with my parents. I remember only about five scenes that took place there, all of them tinged with fear. My clearest memory from that time is when I was forced to eat a huge piece of meat. I choked it down; it was very hard to swallow. Worse, I was then forced to eat another piece. I choked on every bite. Then I was forced to drink a fruit juice cocktail. I took a sip and didn’t like the taste. I said I couldn’t finish it and was met with screaming. I drank the whole thing down, too terrified to say how disgusting it tasted.

Life continued, punctuated with a lot of beatings and screaming and rage. I don’t remember any calm moments save for two: one was my birthday, and the other is me hiding behind the living room couch in the dark, happily playing in the dim glow of a small lantern with some matchbox cars.

Fear was the only feeling I had when I saw my father, and the fear grew every time he decided to try and explain some school lesson I hadn’t understood, and every time he helped me with my homework. And so I was always torn about whether to go to him for help or explanation or risk getting a bad grade and thus an even worse explosion of fury when he found out. Once, this led me to forge a grade on my report card, which at that time was written out by hand. I added a 1 next to the number already there before handing it over to him. The forgery was so clear he clocked it at first glance. He quickly asked whether I’d added the number in my own writing, and I knew right away I’d be severely punished. I couldn’t answer; I was too afraid. To my shock, he didn’t react. He didn’t lecture me about forgery, he didn’t get angry, he didn’t ask why I’d done it. For days I kept waiting for his punishment, for his rage to come down on me, but it never did.

I got used to sudden outbursts, to explosions of rage without warning. Time went on, and it didn’t seem like there was any other way that my father knew how to interact with me. But then suddenly one day everything changed. I remember I’d gone with my mother to visit one of her friends in the hospital. As soon as I entered the building I was struck by an acrid smell, chemical and unnatural, and I was overcome by nausea. We entered the patient’s room, who seemed happy to see us. I sat next to my mother fighting the waves of nausea and the urge to throw up, terrified I’d dirty the clean hospital floor. The visit ended and I walked out slowly next to my mother. A small measure of bitter bile rose up from my stomach and into my mouth. I fought to keep it in, to swallow it down, terrified again of dirtying the clean hospital floor. Once we stepped out into the wide garden surrounding the hospital, I took a few deep breaths and the nausea subsided, but the fear of having to throw up remained. Some minutes later I was seated in the back of our car, my father driving, my mother next to him, and my little sister next to me. Nausea overwhelmed me once again, and with it the terror of throwing up and dirtying the clean car. I fought it hard, swallowing down my vomit again and again. I thought of asking my father to pull over so I could heave, but the fear of his sudden rage kept me silent. In the end I couldn’t hold it in anymore, I opened the car door and threw up outside. My father was shocked and my mother shouted at me to close the door, berating me for having opened it while the car was moving. But my father said nothing. Later when we were back home, I remember her blaming him, telling him I’d done what I did because I was “afraid of him.” This was the first time I’d heard the word “afraid.” I didn’t fully understand what it meant; it would take me months to link that word to what I was feeling. What confused me even more during that time was the fact that my father changed his behavior toward me completely. He stopped beating me and his outbursts decreased dramatically. But the fear was there to stay.

Were there happy times? Of course. But I don’t remember any of them. There are only some static snapshots in my mind, my family members smiling, the context lost to time.

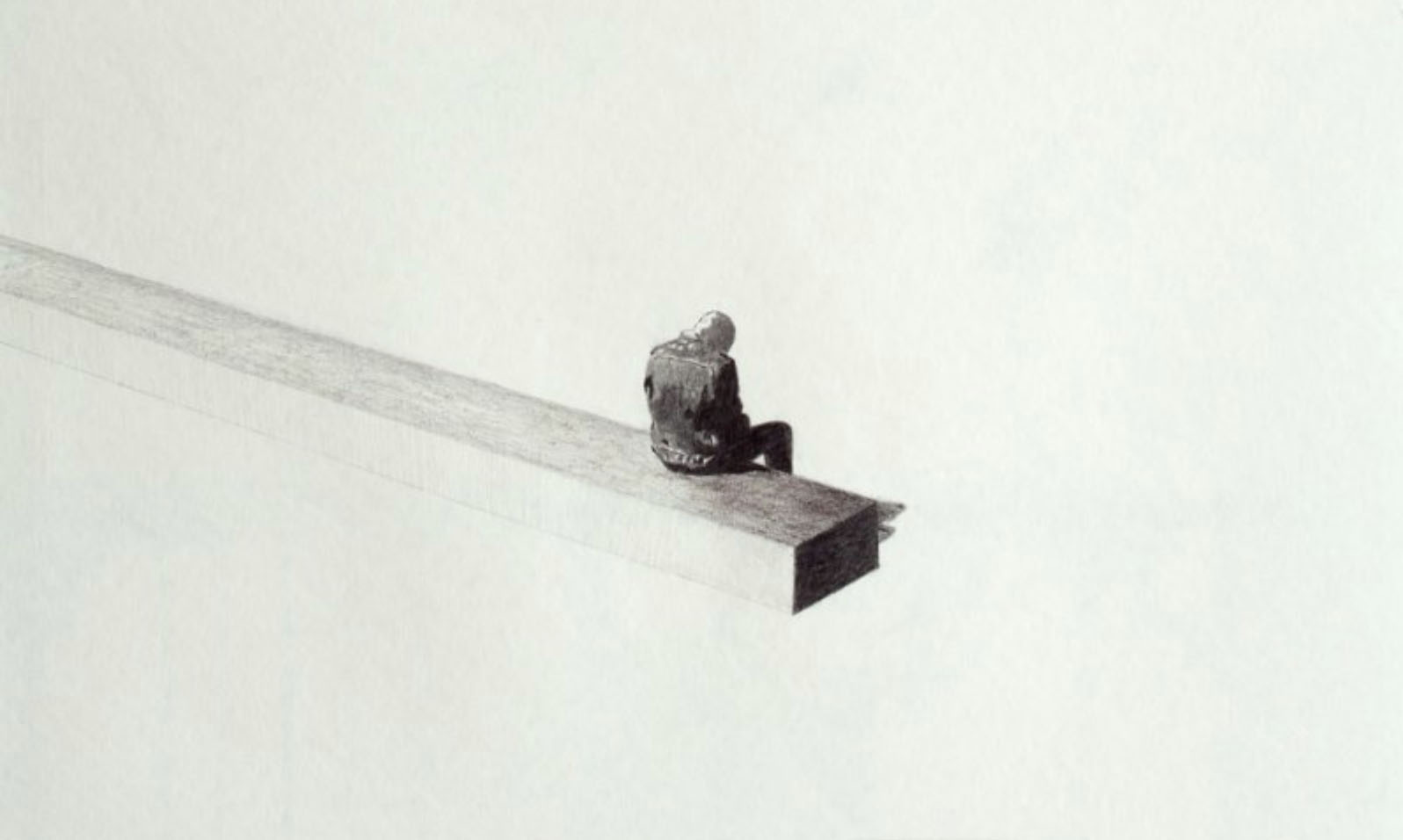

It’s hard for me to describe my fear. I suppose everyone has a different way of describing what frightens them. When I turned 30, I remember I was in Kuala Lumpur. I climbed to the top of a mountain outside the city. It was a few degrees colder up there than it had been at the foot of the mountain. The smell of the forest was fresh and invigorating and the fog exceedingly close. My consciousness drifted into the surrounding calm. The fog crept slowly closer, half-white and damp, and when it surrounded me completely and I could no longer see anything around me, all the fear inside me sharpened into focus. The terror was so overwhelming I couldn’t move or think or remember anything; I felt nothing but fear. I knew then that I was inside the purest form of terror. Inside a cloud of fear.

Half my childhood memories are of fear, which only kept increasing. Fear of failing at school, of crossing the street, fear of my classmates and their bullying and violence. Once I remember finishing a final exam — there were only two more exams left, and two days off first, which meant I had a few long hours of leisure before me — and so I went with a couple of friends to a football field near the house. We played a little and then — for some totally unknown reason — one of my friends erupted into a fit of anger. He grabbed my hand and twisted it shockingly hard, and he kept hold of it in that strange, painful position for a minute or longer. I was paralyzed by pain and fear while he screamed insults at me. Not for a second did I wonder why he was doing that. I didn’t ask him, nor did I respond to his insults, or try to free myself of his grip or strike him with my free hand. Fear prevented me from any of this. The thing I was most terrified of was that he’d break my hand and that I’d have to tell my father to take me to the hospital. I was afraid of how angry his reaction would be, afraid of losing study time, and of not being able to sit for the coming exams. The only thought I could focus on during that long-ago moment was when the whole situation would end. When he finally let go my hand, I just walked away without a single word.

I remember a shouting match full of curses slung between two teachers I admired greatly, appreciating their skill at explaining difficult math problems with clarity and ease. It shocked me to hear them using such language, and I was also shocked that after exploding at one another like that, flinging such curses and insults, the whole thing ended the way it had begun, suddenly and without warning. I remember there was an Arabic teacher I loved for the same reason, because he explained things perfectly. I loved his voice and the distinctive way he had of pronouncing his words, and I knew and played with his son who was one year older than me and that just added to my affection for him, it made me feel like there was an extra bond tying us together. And so I was stunned when one day in class he suddenly slapped me across the face. I didn’t understand at first why he’d done it, and I didn’t even realize that he was also beating the classmate sitting next to me before kicking him out of class altogether. It took a few minutes for me to realize he’d done this because I’d been talking to my classmate. I had no idea what to do after all that. Was I supposed to apologize to the teacher? To my classmate? One thing was certain: from then on I was too afraid to speak in class.

That was when my own fits of rage began. The first to witness them were my brother and sister. I’d shore up all the reasons I had to be angry with them until I exploded into hitting, screaming and fighting. I saw the shock and fear in their eyes when this happened, and now I know that they had no idea why. Over time, it felt like they began to distance themselves from me, even though we lived under the same roof. These outbursts of rage became a recurring event, sometimes more frequent, sometimes less so, and always without reason or rhyme. I couldn’t control my anger at all, and I never even tried. Then it escalated. I began raging at my classmates and friends. Back then, when we were kids, these outbursts passed without anyone really noticing. We were all rough with one another; fighting, curses, insults, and what I would later come to know was called “bullying” were everyday affairs at school.

But some years after graduating, I slowly began to realize just how destructive my angry outbursts were. The worst one my friends ever witnessed was when we were all in a car that belonged to one of them. I have no idea why I exploded, screaming at him to stop the car so I could get out. It was such a strange and sudden request that he just ignored it, and so I flung open the door while the car was still moving and made to jump out. Everyone started shouting that I was crazy, a psycho, until my friend finally stopped the car and I jumped out for real and tore away. Two friends ran after me, trying to convince me to come back. They asked me why, what had happened. I was no longer a child; now, as an adult, I was expected to justify my actions. But my rage was so overwhelming — even though I can no longer remember its spark or reason — that I refused to speak to them at all, instead storming thoughtlessly down the street. When they returned to the car and I was once more alone, I calmed down instantly. The street was totally empty of both cars and passersby — a rarity in Cairo. A minute later, a taxi passed; I hailed it and got in. Somehow the driver noticed my state of tension and he grew afraid. He stopped the car and asked me to get out. When I protested that the streets were deserted and I wouldn’t be able to find another cab to take me home he exploded at me, shouting until I got out. I walked for some minutes down the empty street, then I heard a car speeding toward me from behind. It seemed like the driver was steering deliberately close to the edge of the road where I walked. There was no sidewalk, just asphalt giving way to earthen terrain. As the car neared me, it suddenly swerved sharply, as though the driver meant to hit me, or at least terrify me. I fled the road, sprinting into the dirt terrain to escape. When I glanced back, I saw that the car had pulled over, and a man with a dog had stepped out and was making toward me. The dog began barking furiously and I could see from afar that the man hadn’t unleashed him yet. I ran faster, away from the dog and his owner. I was terrified the man would let go of the leash and the dog would come after me. That’s the last thing I remember. I don’t recall how it ended or how I got home, but I do remember I didn’t sleep a wink that night. I remained wide awake in bed until dawn, plagued by a splitting migraine and an overwhelming sense of misery. To this day, I still don’t speak to any of those friends.

I don’t know of a single friend who hasn’t experienced the kind of bullying or violence or anger that frightened them. Often when a friend has spoken to me of such experiences, it was with a smile, and the word “fear” was never mentioned at all. They’d tell me what happened, and I’d remain silent. An admission of fear is an indirect admission of being a “woman.” To the listener, the speaker is immediately removed from the category of men and placed in that of “ladies,” and this is followed by a change in how the speaker is treated. The change happens gradually, like a long, slow testing of just how “female” they are. Hangouts become fewer and fewer. Specific words are used. Words like “fear,” “manly,” “girly,” “fag.” It becomes even clearer when some more complex phrases appear. Such as: “We only hang out with men.” Or, “How are your girlfriends doing?” Or, “We know this guy who’s really, really good at cooking.” It doesn’t stop at words, but escalates into physical assault or harassment designed to humiliate and to cement the idea of being “feminine” in the frightened person’s mind and in the minds of all those around him. One of my friends figured out that his revulsion for liver stemmed from a traumatic childhood experience. He was too afraid to say anything about it at the time and it persisted until he finally overcame it when he was much older. And he didn’t tell me this until he was 64 years old. Another friend is afraid of eating fish to this day for a similar reason. He never told me himself; someone else revealed it in his presence and I watched the shame and anxiety take over his face. A third friend, vegetarian, told me he’d been repulsed by meat since childhood. Then, with embarrassment, he went on to tell me that a relative had told him he’d witnessed an animal being slaughtered as a child and that this was why he hated meat. But no, he insisted, his voice hardening, he didn’t think this was true and furthermore he recalled no such incident. What I do know is that a person is able to overcome their fear, whether due to the passage of time, or due to experiencing another trauma, or even by making peace with what frightens them. And maybe if a person is able to declare all the reasons for their fear, they might also learn to tolerate other people judging them for feeling fear in the first place. But an imprint of fear would remain inside them forever.

My fear didn’t abate with adolescence, nor did my exposure to anger, harassment or bullying at the hands of others. Three times I had the experience of what we called “being pinned:” walking down a quiet street and then being stopped by someone who made like he wanted to ask me a question before pulling a folding knife out of his pocket and flicking it open. He’d place the blade to my throat or hold it up to my face; he’d ask me for money or apologize for what he was doing, or he’d justify his behavior by telling me he’d just come out of prison and didn’t have any money. It was a common line that was used back then, and it was one that immediately played on my pity and fear. Once, on one of those three occasions, I was standing at a bus stop alone. The man approached me and without a word whipped out a small box cutter and placed it to my throat. He said nothing, asked for nothing, just held the cutter blade to my neck for about a minute as he stared into my eyes and smiled. Finally, he lowered the blade and walked away. I had no idea what had happened or why.

I remember once I was seated with two friends on a small patch of grass, the kind you usually find in the middle of the wide pavements of Heliopolis. One of them headed off to the nearby kiosk to get us something to eat. He returned less than a minute later, his face white with shock and his hand bleeding profusely. We tried to stop the flow of blood — my hands became stained with it — but it was impossible. Quickly we were able to hail a cab for Heliopolis Hospital. In the taxi he told us that some man had brushed past him, grazing something against his palm, only to notice that the man had actually slashed the back of his hand with a razor or box cutter. He said the pain only came a few seconds after the cut. I looked at his hand, whose bleeding he was still trying to staunch, but in the gloom of the taxi could make out nothing but the darkness of the blood.

When we got to the hospital, all three of us were met with abuse and mockery from the nurses. They accused us of being thugs, fags, they said we’d been in a fight with other degenerates like us and that they’d beat us and cut my friend’s hand because we were sissies. With that, one of the nurses placed a big pad of gauze on my friend’s hand. When he lifted it, it had soaked up all the blood. That’s when I saw the wound, as wide as his entire palm. It didn’t look deep, just like a long red line. And then it started bleeding profusely again. The nurse said the injury was definitely the result of a razor blade, and that we had to go to the police station and file a report before coming back to the hospital for treatment. I don’t remember what happened afterwards, but I know that that was the last time the three of us saw one another.

I remember I heard about a classmate who’d pressed a razor up to another’s neck and given it the slightest little drag. He hit a major artery and the blood came spraying out. Despite being surrounded by people, no one could do anything. The guy bled out and died in just a few minutes. Later it was said that this had been only “horseplay,” that the guy with the razor never meant to kill his classmate, nor had any of the bystanders expected he’d die so quickly. Stories like this — and there are too many to recount — leave me more terrified than those where people are pinned or robbed at knifepoint.

My fear persisted past adolescence. No one intimidated me in the old ways any longer; now there were new methods for it, both direct and indirect. I faced numerous attempts at intimidation from colleagues and friends, though most of them came from strangers I didn’t know. It seemed like no one quite grasped the gravity of what they were doing. Rather, they seemed to take pleasure in it, or to be acting with some aim or gain in mind that I couldn’t see. I remember once being in the metro, the car half full, when I heard a flat, quiet voice from behind me. I turned to see a fat policeman standing in front of the closed doors; I could see a reflection of half his face in the glass. He was staring right into his own eyes, the glass semi-mirrored due to the difference in the light inside and outside the metro car. He’d intone the name of some officer and then follow it up with a curse. Like: “Colonel Mohammad Ali the homo.” Then, “Major Fathi the pimp.” Then, “Lieutenant Medhat the homo.” He intoned the phrases clearly, slowly, calmly, without emotion. He didn’t shout, he didn’t grow agitated. He just went on in that audible, confident voice. When I turned to look at the other passengers, I noticed that everyone was unusually quiet. No one looked my way or at the police officer. I was the one standing closest to him in the car. I expected him to explode in anger at any moment. I thought about moving away, but fear kept me fixed in place. Instead of getting off at the next stop to escape, or even getting off at my own stop, I continued to stand there next to him, listening to his words. I’d breathe a sigh of relief when he grew tired and stopped for a minute, but then the fear would surge anew as soon as he started talking again. He kept going on like this until he finally disembarked at one of the stations. I didn’t feel free until the metro doors closed safely behind him. I got off at the next stop, feeling relieved as I walked along the station platform. I’d gone very far from my own stop and had to take the stairs so I could cross over the platform and take the metro going in the other direction. As I climbed the stairs a suffocating sense of misery overtook me. I felt no pity for the officer, and all my brief relief dissipated. The misery, however, persisted for days.

I had never connected them into a pattern — fear, anger, relief, misery — but over time I grew to see it as a cycle that went like so: fear, accumulated over years, revealing itself suddenly. An explosion of anger that went on for some minutes. A fleeting, ultra-brief sense of relief. And finally, a misery settling over me for hours or days. Sometimes the relief would be missing from one of the cycles. Sometimes my anger erupted only in my mind without ever revealing itself in my behavior. Sometimes the fear would disappear even though I could feel its imprint still and knew it to be the source of everything that was happening. The clearest thing about each of those four emotions was their duration. I knew each one would end after a time, but I had no idea how or when, save for the misery, which was the longest-lasting and worst of them all. Sometimes I felt the misery would never end, that it would remain my eternal prison. When it overtook me, I could see nothing else. I couldn’t picture myself in the fear, the anger, the relief. But under the grips of misery, it was all I could see.

My angry outbursts grew more and more frequent; I didn’t even try to control them. They were directed at everyone around me: friends, family members and work colleagues, even strangers. In turn I was also on the receiving end of similar outbursts, from people I knew and others I didn’t. The reaction to them was always silence, whether on their part or mine. No one had the courage to ask for the reason behind these eruptions. I lost a lot of friends because of these fits of rage, and at some point I decided it was time for me to start being more careful, to start paying attention to how much it was costing me — so many people, so many old friendships that were now gone forever. I understood without a doubt that my rage would come on after an accumulation of fear — old fears from childhood, atop which were piled new fears from the years following, until something, some word I heard, some act I witnessed would act as the trigger for my rage and out it would all explode.

Years ago, I realized that there was a way for me to control my anger: by always assuming the worst. It was incredibly successful; my outbursts decreased considerably. If I wanted to get some document from a government office, for example, I had to assume that it wouldn’t happen on the same day. And if indeed I didn’t get it — which is what usually happened — I wouldn’t get mad. If I tried to make a new friend or start a new relationship, I had to assume that I would fail. Then, if I failed, I wouldn’t get mad. And so, assuming the worst seemed to be an excellent solution, or at least the best one I’d found thus far.

As time went on, however, I realized that I was constantly expecting the worst in every situation, and this made it impossible to enjoy anything. I stopped watching movies, stopped reading, stopped listening to music — and this went on for years. For years I stopped trying to make new friends or get into new relationships. And though a life like that seems quite sad, it was also truly peaceful. The cycle hadn’t changed, but the anger was gone.

Then I tried to re-engage with life, while keeping this rule of assuming the worst. Of course, it was a complete failure, because by then the slightest mental effort caused me pressure which was then followed by anxiety. Everything grew dull to the point of burden. I grew used to forcing myself to read a book only to abandon it some five or six pages in; to entering the cinema only to fall asleep fifteen minutes into the film; to going out with a friend and then excusing myself and heading home after a few minutes; to going out on a date with someone new, maybe to start a new relationship, then having the whole thing fizzle out in fifteen minutes or so. I’d pay the bill and leave — the café; the person sitting there either stunned or angry; everything — without even turning to look back. My fear remained a heavy weight. The anger, of course, was gone. The periods of relief grew shorter and shorter, while the misery increased so much it left me totally exhausted.

Even those emotions that are usually desirable, like love, attraction, relief, all made me anxious. My reactions confused everyone around me. Even after stifling my anger, I still couldn’t communicate properly with many people. Expressions of admiration were met with coldness, expressions of love with angry rejection, and relief made me fearful, because I knew very well that the feeling was temporary, and would be followed by something awful.

I remember once I was in Beirut on vacation with my family and was surprised to find that one of my friends there had been admitted to the hospital just a few hours before I arrived. As soon as I checked into the hotel, I left to go visit him in the nearby hospital. When I saw that he was in a stable state I was relieved. I stayed by him for a little and then left. I walked back to the hotel from the hospital, and thought a lot about his illness, about his situation and how he didn’t deserve what had happened to him at all. But I also thought about how he was receiving the best treatment possible, and that he was surrounded by the people he loved most, and so doubtless he was as well as could be. I noticed a message my wife had sent while I was in the hospital saying she was going to take a short nap while I was away. I walked on, until I came across a bakery selling mana’eesh. I bought a zaatar manouche and a box of apple juice and sat down on a flower planter across from the bakery to eat, taking pleasure from the saltiness of the thyme and the coolness of the juice. The two sensations together were the very embodiment of the relief that engulfed me at that moment. When I finished, I continued on to the hotel, and with every step, the grasp of misery gradually tightened around me. Just before I got to the hotel I thought, no, I shouldn’t surrender to it. I’m on holiday with my family, I need to enjoy this. I turned right around and walked back in the opposite direction, back to the bakery. I thought that returning would loosen the misery, the same way that going forward had tightened it, but every step increased its chokehold. When I got to the bakery, I kicked myself for the naivete of my logic. The misery maintained its grip over me the entirety of my stay in Beirut.

I was in my 40s, having given over to fear entirely when I was forced to have an MRI scan of my brain three times within the course of a few short months. The first time, I was afraid they’d find an aneurysm, or maybe a tumor in its early stages. The technician performing the scan asked me to leave anything metal behind in the locker before entering the MRI chamber, and then he helped me lie down on the gurney that, a few minutes later, would slide me into the machine. He placed a huge pair of earphones on my ears to block out the annoying noise from the machine and instructed me not to move a muscle while I was inside. The whole thing took about half an hour. I was so terrified of the results, which the tech typed out quickly, that I’d barely registered all the annoyances of being inside the machine. I returned to the doctor who told me that all the results were normal. Still, I had to repeat the same scan two more times because the doctors couldn’t understand what was happening to me. When I went to a new doctor, he said that everything I’d done over the last months had been useless and that now I had to undergo four brain scans. By then I’d developed methods to overcome my fear of being inside the machine. Overcoming the fear of being in an enclosed space like a grave was easy; I thought about how when I’d die I’d feel nothing, and so comparing the machine to a grave was meaningless, besides the fact that I had no idea whether I’d be buried or not. Overcoming the irritation at the noise of the machine was also easy; I imagined I was listening to a long dubstep track. It was amazing how similar the sound was to a dubstep beat. I actually found myself enjoying the variety and sudden changes in the machine’s sound, even if it never rose to the repeated crescendos typical of that kind of music. I managed to do a lot of things inside the MRI machine: to think about how I’d feel nothing when I died, to imagine that I was listening to a long music track. What I didn’t manage to do was keep my head and shoulders still as I lay there. I tried to distract myself by thinking of a lot of different things but I’d fail every time and go back to thinking about how I had to keep myself still. An hour and a half of trying to move away from the thought of holding still and then looping right back to it. I tried to banish from my head the thought that I’d moved and would thus have to repeat everything all over again from the beginning, but it was impossible.

Finally, the machine stopped working and I got up from the gurney overwhelmed by relief. I left the MRI room, greeted the nurse and made my way to the stairs. As I descended, the relief dissipated and the misery took over with a slowness and heaviness I’d never experienced before. I felt like this time, the misery wanted to do something unknown to me, that it was no longer simply content to dominate me. I had no idea why I stood transfixed for an entire hour before the radiology center building, even though numerous taxis passed before me without me ever trying to flag one of them down. I had no idea why I sat in the taxi without moving a muscle. I had no idea why I spent the rest of the day sitting on a chair at home rigid and frozen. I could hear my phone vibrating, announcing the arrival of message after message. But I didn’t care, I remained firmly seated on that chair. That night I slept flat on my back, my head and shoulders held rigidly, my arms lying straight at my side. I didn’t move, nor did I sleep. Morning came, only to find me in the same position. I spent the next day in the same wooden state: before the bathroom sink, on the toilet, at the window, at my desk, and in the evening, on that same chair. Finally, I reached out my hand and picked up my phone to see what messages I’d received. I saw that one of my friends had sent me a screenshot of a tweet that had been written about me. I didn’t care, despite its harshness. A few minutes later, someone I don’t know sent me a link to a tweet thread posted by the author of the first tweet. It essentially contained a bunch of information about me and my wife, all things that were easily discoverable through our Facebook or LinkedIn profiles, but just the twisted way in which the information was presented made it sound like I’d committed some crime instead of just going about my normal life. One of the tweets included a clear threat to create a fake account accusing me of being a harasser and a frequenter of brothels in Europe and a pedophile. The poster said that doing so would be extremely easy and that all these accusations were supported by something I’d written in one of my novels. Such a threat ought to have terrified me, but I read the tweets coldly, without any reaction passing through my mind. I didn’t even think to take a screenshot of the tweets, particularly the threatening one. Three days later, after the misery had eased some, I remembered what I’d read and was truly frightened. I went to the poster’s page and found that he’d deleted the entire thread. It became clear that he’d just wanted to scare me. I didn’t wonder why he’d done it, but I did wonder quite a bit at my coldness, my lack of reaction when I’d read the thread the first time. Then I realized that the that the tweets hadn’t scared me because the misery had surpassed itself to such an extent that it no longer merely dominated me, but maybe acted on my behalf, desiring and planning and actively working to harm me. Distracting me from what actually threatened me, and doing this in its own convoluted way. It was its own creature, taking meticulous, thorough pleasure in hurting me.

In a state of misery, every memory seems a catastrophe that evokes shame. Everything happening around me seems obscure, carrying negative meaning. Every sentence I hear sounds like blame or mockery or criticism or judgment; every movement is a kind of pressure, a kind of insult. At the same time, it feels like every word I’ve uttered in the past is an offense for which I need to apologize. I find myself compelled to apologize for things I did or said years ago. And every apology surprises the other person, because they can’t remember any of what I claim to have said and done, or because they don’t think any of it deserves an apology, and all of this only serves to deepen my shame. A shout escapes me because I can’t apologize to a dead friend. I repeat apologies to someone until they grow irritated and stop responding. I feel like I must now apologize for apologizing too much and I don’t know what to do. I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror and realize that I thoroughly despise my own face. I turn away, trying to forget it, but it follows me. I imagine myself excising it from my imagination with a razor blade but it remains whole, pursuing me. I realize I’m unable to look anyone in the face, so I’m forced to walk with my eyes fixed on the ground. I turn over every sentence in my mind before I utter it, afraid the other person will misunderstand me. I try to formulate my sentences as simply as possible before speaking. I fail again and again, until I announce loud and clear that I don’t know what I’m saying, that I in fact have nothing to say, and the conversation sputters out. I speak to others with my eyes fixed on something behind them, or on their hands, or on their chests. I’m flustered when someone notices me looking past them and waves their hand to get my attention. They usually do this playfully, but it shuts me up nevertheless. I’m flustered when a man shoves his hands into his pockets after he notices me staring at them and I no longer know where to direct my gaze. I’m flustered when I realize that I’m staring at the breasts of the cashier and I no longer know where to direct my gaze. The only solution is to close my eyes so I see nothing. But the idea remains fixed and foremost in my mind: that none of this should be visible on my face. I have to remain neutral and calm, and if I notice any doubt creeping into the other person’s expression, I need to smile and say something pleasant.

Is there any escape from all this? Of course. There are medications that a doctor will prescribe if I visit. I know by now that this cycle is out of my hands, it is the result of a jumble of hormonal imbalances, damage affecting specific areas of the brain, and the fear that has lived in me since childhood, increasing daily. Medication might help balance these hormones and regenerate some brain cells, but it would never erase the imprint of fear.

Yet there is another, very effective escape that I know as a result of long experience: to wait for the next sense of wonder. The wonder might arrive as a result of something simple, like the sight of a tree in the forest, or a sip of water on a sweltering day, or the taste of a dish I’m trying for the first time. It could even be something more complex, like a phrase graffitied on a wall, or a fascinating new friend, or the love of someone new.

The wonder forces me to contemplate it. Trying to understand: how do those trees in the forest live? Why did that sip of water calm me so? Why do I remember the taste of that food? What did that graffiti artist mean by that phrase on the wall? Why didn’t that new friend label themselves, even though they’re impossible to label? What is the difference between love and obsession? Are they the driving forces behind all that I’ve written? That sense of wonder is the only thing that pushes me to overcome my fear. It disappears my anger and leaves me in a state of peaceful relief for several days. The misery, meanwhile, loses its edge and relentlessness. The cycle continues to repeat itself, but the duration of each emotion is disrupted, a disruption that works to my advantage. And because the cycle repeats itself monthly while a wonder reveals itself only once a year or even less, that waiting makes me appreciate it all the more when it finally arrives. It is this sense of wonder that makes me rethink everything I’ve felt and done, rethink the effects of this fear that I must learn to deal with. It allows me to see that constantly planning for all contingencies isn’t the best way to deal with the world around me, that maybe “going with the flow” is better than “planning for what I wish to have happen.” That wonder is capable of relieving me, giving me joy, pushing me toward the kind of change I’ve been resisting for so many years.