After a long and bloody civil war, and the banishment of Bashar Al-Assad, Syria’s artists are beginning to return, and exhibit new work, at home and abroad.

Arie Amaya-Akkermans

During the long decade of the Syrian civil war, artists have found safe havens not only in Europe, but also in Lebanon and the UAE; the exhibitions Wavering Hope by Ayyam Gallery and Tracing the Unseen: Landscapes of Memory and Metaphor at the Atassi Foundation opened recently or will open soon in Dubai, but as the Assad regime came to an end, Syrian artists began to ask themselves whether it was time to go home and the answer was not always hopeful.

More than 11 years ago, an exhibition on the topic of the Last Supper, as painted by Da Vinci and representing the scene of the Last Supper of Jesus with his disciples, took place in Beirut, bringing together a group of over fifty Syrian artists. Most of the artists involved were living in Syria, although some of them had already relocated to Beirut, and the exhibition intended to demonstrate that cultural life in Syria continued in spite of the war. While visiting the exhibition, to meet many of the artists, with war correspondent Catalina Gomez, we tried to make sense of what it means to produce and exhibit art in such a convoluted moment: A refugee crisis with repercussions in Lebanon, the threat of Daesh, and the fear of the Syrian war spreading to Lebanon.

At the time, I wrote a review of the exhibition, focusing on the work of artists Yamen Yousef, Alice Al Khatib, Lama Hajjar, Mazel Al Feel, Husain Tarabie, Fadi Al-Hamwi, and Alaa Hamameh. Since then, so much has changed in the region — it would be the last time they would be exhibited together. For a number of weeks in April and May 2014, we all spent a lot of time in their temporary studios, mostly discussing the war and the elitism of the contemporary art world. But rapidly enough, they started vanishing: Yamen and Lama returned to Syria, and the rest emigrated to Europe at one point or another. The final conversations, in the frenzy of Beirut’s long nights, were punctuated by the uncertainty of whether we would all meet again.

The answer was no.

In Syria, the regime of Bashar Al-Assad collapsed in the blink of an eye at the end of last year, ushering a turbulent era, under self-appointed president Ahmad al-Sharaa, a former leader of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a Sunni Islamist group and paramilitary organization, widely considered in the West as a terror group. The weeks that followed Assad’s last minute escape to Moscow were exciting for any observer, and filled with rumors, conspiracies, questions and theories of all kinds. Did the Assads fly their money out to Dubai? Where was Bashar’s brother, Maher? How could HTS regain all this territory almost overnight?

The questions remained unanswered. But during those first weeks, amidst ecstasy and confusion, in the absence of political clarity, the idea of the return of cultural life to Damascus took over the journalistic imagination. This narrative matched the false European consensus that it was now safe for Syrians to return home, and it was predicated on the euphoria of the moment, from the safe perspective of cultural practitioners well established in Western countries. That kind of spectacular return of course didn’t happen and the topic rapidly died out.

It’s not only that Syrian artists and cultural workers are not returning, but that Syrians are not returning at the rates Europe expected: Numbers vary depending on whom you ask and when, between half a million and two million — the International Organization for Migration (IOM) puts this number at 750,000. According to Alex Simon of Synaps Network, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is regularly publishing deceptively high figures about the return of Syrian refugees, as a means to fundraise for its own programs. The organization regularly updates the numbers of how many Syrians have crossed, without accounting for the many that crossed and then returned, especially to Lebanon. The data doesn’t distinguish either between refugee returns and internally displaced persons. Lebanese president Joseph Aoun recently stated that 300,000 Syrian refugees would return to Syria before the end of this year and be given $100 in exchange for a pledge of not returning. The plan is as unrealistic as the 2 million number of the UNHCR based on surveys from December.

Conversations with NGOs and journalists that have traveled back and forth between Syria and Lebanon, suggest that many of the returnees are refugees in border areas of neighboring countries such as Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, who might have been living in camps for years and are presumably in worse economic conditions than the people living inside Syria. The country is obviously not ready to absorb them, amid massive unemployment, inflation, impoverishment and severely damaged infrastructure, which IOM, another UN agency, warned about at the end of 2024, highlighting the complex ecosystem of international aid today, where different agencies of the same organization compete for limited resources, influence and political favors.

The professional class has largely stayed away and continues watching the situation, sometimes with hope, sometimes with horror. A diplomatic source in Austria told me that of the 100,000 Syrians living in the country, only about 250 have chosen to return, and the numbers in Germany were less than 500, for a country that hosts over a million Syrians. Gallerist Roula Suleiman, from Zawaya Art Gallery, one of the few art centers still open since the beginning of the new era, says that many Syrian artists have visited from Europe, especially in the early days, but nobody would remain for too long — the material conditions are far from sustainable. Suleiman tells us half-jokingly that it would be more profitable for her to run a shawarma shop, and explains that the gallery is not financially sustainable.

There are no art collectors left in Syria.

Suleiman’s position that artists need to wait and see how things unfold in the country, coincides with the view of Christopher Foulkes, a migration researcher at the Australian National University, and formerly an IOM officer in Gaziantep, overseeing aid to Syria. “Particularly amongst educated Syrians, such as those who work in the culture industries, there has been very much a wait-and-see approach taken to the question of return,” Foulkes says. “Given that the new government is more explicitly Islamic than the Assad regime was, there’s still skepticism on the part of Syrians regarding whether they will be welcome by the new authorities.”

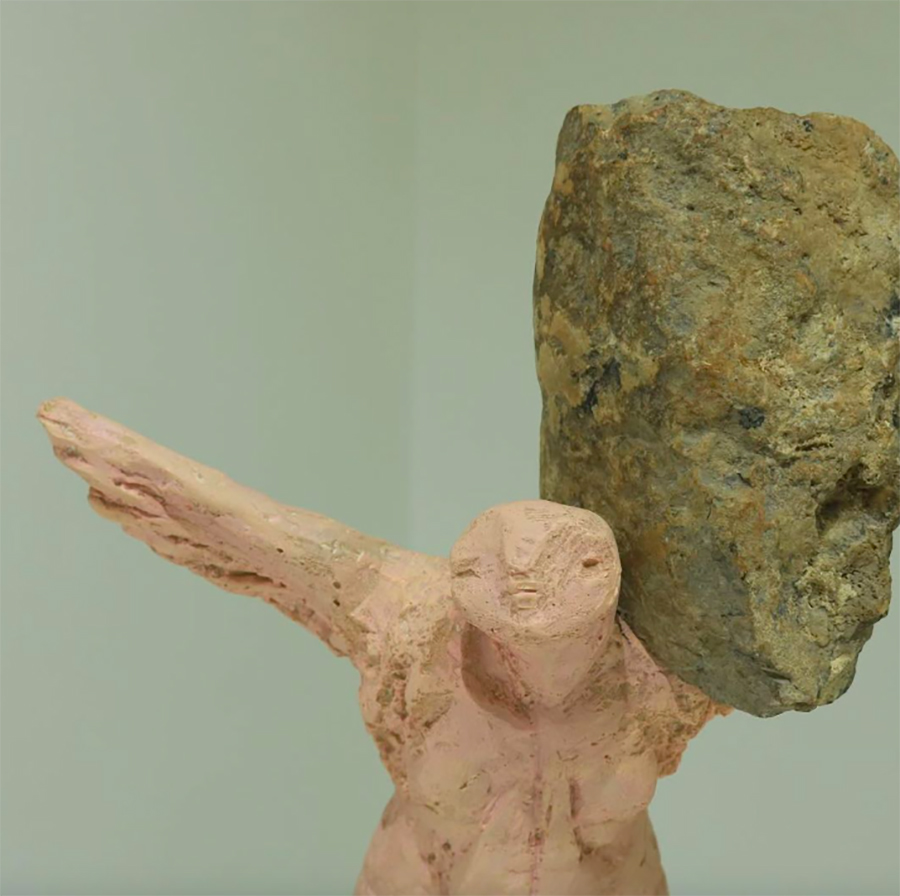

Speaking on the phone with Yamen Yousef, now a resident of Beirut, I learned that he is not returning: In fact, the sculptor spent most of the war in Syria, but two years ago, weary from the lack of opportunities and infrastructure for the arts, he left for Beirut, where there’s a dynamic and resilient environment. In any case, for over a decade, he’s been represented by a Beirut gallery, Art on the 56th, established in 2012, which has consistently introduced young Syrian artists. After the collapse of the Assad regime, he joined the joyous celebrations in Damascus for a couple of weeks, but then the massacres began in the eastern coast, and as a native of Tartous, it wasn’t safe for him to stay in Syria.

In Beirut he is not alone; another young artist, Sweida-born Anas Albraehe (1991), moved to Beirut in 2016 and since then has seen his career flourish. A talented painter with a unique expressionist style, he’s been exhibited by some of the best galleries in Lebanon, and is now represented by a trendy French-Colombian gallery in Paris that has taken his work recently to Art Basel, the most prestigious art fair in the world. This makes Albraehe perhaps the most successful artist from the years of the revolution who wasn’t trained in the West. Both Yamen and Anas, among others, remain highly critical of the new regime, and constantly point out their abuses of power — from the safety of the distance. There’s very little to indicate that artists are returning en masse to Syria to rebuild the country’s cultural life, and in the course of my inquiry, I wasn’t really able to find any recognizable artists that made the return home. However, Yamen Yousef pointed out to me, for example, that mid-career artists Mohammed Khayata and Youssef Youssef returned to Damascus from Beirut, although their work is primarily still based in Lebanon.

But at the same time that doesn’t mean artistic life in Damascus is stagnant: Only a few months after the fall of the regime, collective exhibitions, screenings, talks, plays, performances and discussions were being organized that triggered an animated debate. To name a few, the exhibition Path, organized by the Madad Art Foundation, (reviewed in TMR); Detainees and Disappeared, presented by the collective Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution at the National Museum of Damascus; Remnants of Memory by Ghazwan Assaf, organized by the Ministry of Culture at the Arab Cultural Center in Al-Maza, which created replicas of destroyed Syrian interiors; and the day-long workshop “On Cultural Practices and Artistic Transformations in Syria,” organized by the non-profit Ettijahat.

A paradoxical tension exists between the desire to bring culture back to the country, narrating the tragic history of the war and the impossibility of luring Syrian artists back to a country that entirely lacks the infrastructure to support their practice. But nothing is ever transparent in Syria, and the exhibition Path, widely publicized in regional media, is a formidable case in point: Dwelling on the topic of forgiveness, 29 Syrian artists brought together different narratives about the ongoing grief of the country. The exhibition was held at the unfinished Massar Center, conceived in the shape of the Damask rose, by Danish firm Henning Larsen. In the narrative of the exhibition, the reclaimed building served as a metaphor for the current state of the country, since its construction was halted by the war and never resumed.

The building was a project of the Syria Trust for Development, an NGO established in 2007 that was effectively a government body under the control of Asma Al Assad, who was accused by the Syrian Network for Human Rights, of using STD as an umbrella organization to establish a near total monopoly of the development sector, receiving large shares of international funds earmarked for reconstruction and recovery, earning enormous profits and embezzling humanitarian aid. Reclaiming the building temporarily for an art exhibition about forgiveness is of course a welcome gesture, but the story of its organizer, the Madad Art Foundation, might be closer to the former regime ranks than its apolitical statements about art as healing suggest.

One of its founders, a much celebrated Syrian artist and philanthropist, Buthaina Safi Ali, with a distinguished career both as a practicing artist and a university professor, died in 2024 but bequeathed the foundation a house in Damascus that was at the center of a controversy between local artists and HTS militiamen at the end of January. Safi Ali is rumored to be closely related to general Ibrahim Al Safi, a prominent Syrian general and other former members of the Syrian military, currently under international sanctions. As always in Syria, no such information can be confirmed by anyone, but a memorial ceremony held by the National Center for Visual Arts after her death, had a remarkable list of attendees: The secretary of Baath Party branch in Damascus, Hossam Al-Samman, representatives of the ministries of higher education and culture, and the center’s director, Ghyath Al-Akhras, an uncle to Asma Al Assad. It’s hard to tell what these relations mean for the world of art and culture in a milieu where opacity is near total.

Although many cultural actors in Syria have insisted repeatedly in media interviews that art is not about politics and that the government never interfered with contemporary art, the reality on the ground suggests otherwise. During the Assad regime, connections to the government or at least approval, were essential for arts organizations to operate. Syrian photographer Omar Berakdar, founder of the nonprofit Arthere in Istanbul, told TMR: “The damage of the Assad era on art and culture is too deep. Hafez understood the artists’ need for freedom of speech, and therefore kept the art scene under heavy surveillance by Syria’s security apparatus. All that was left was a few annual festivals and some exhibitions here and there, to portray the regime as being modern and open.”

A number of European cultural institutions also operated branches in the country, and they quietly acquiesced to the regime’s instrumental view of culture. However, it would be of course unfair to summarize the extensive history of the artistic scene in Syria only as a tool of propaganda, given the long-standing connections of modern Syrian art to the rest of the Arab world, Europe, and the Soviet Union. But at least on official record, art had to be kept free from politics, which explains the great importance of abstraction in modern Arab art.

A conversation with Roula Suleiman about her gallery Zawaya, founded as recently as 2019, shows the contrast between the Assad and HTS eras and the unpredictable present: Towards the end of the Assad era, she was told that the gallery’s license was exclusively for sales of art, and the Ministry of Culture doesn’t allow under this license to hold cultural events. This restriction no longer exists under HTS, and the gallery has held many events and discussions. But other difficulties exist now: Long meetings with HTS officials discussing the content of the art, a ban on all nudity and the need to cover sculptures for being too representational — therefore forbidden. Many Syrians I spoke to agree that it’s not only that HTS officials don’t understand much about art, but also that they don’t quite know what to do about it, and eye it with suspicion.

Suleiman speaks frankly about how she manages to fly under the radar in times of growing censorship: Living in a Christian neighborhood, amidst the regular presence of diplomats and foreign journalists, which affords her a level of protection. But until when? Nobody knows. She fears that under so much pressure of a new kind, local artists will simply self-censor and change their style to meet the new circumstances. Rumor has it that HTS officials have removed paintings of modern Syrian masters Fateh Moudarres and Louai Kayali from government buildings and replaced them with depictions of mosques, or that there will be a new curriculum in the faculty of arts at the University of Damascus, removing drawing of body parts, working with models, and of course, nudity.

Berakdar, who has exhibited many Syrian artists in Istanbul, in a situation where the local art scene is not open to welcome them, agrees that it will be impossible for artists to return to Syria now, whether short or long term, if there are no institutional structures to support them: “So far, we receive only very contradictory news from the new government and no clear vision.” During the long decade that he has run his non-profit, the Syrian photographer has witnessed that the lives of young Syrian artists in exile look very different than those of established Syrian artists in the West: They’re often battling poverty, homelessness and cruel borders. And some return to Syria indeed, but not to make art; they simply find it impossible to continue supporting themselves for a long period of time, and are forced to return home and face the unknown.

A number of Syrian artists have also found a temporary home in Dubai, and the Ayyam Gallery, founded originally in Syria in 2006, has followed the itineraries of Syrian artists between Damascus, Beirut and Dubai in these two decades. As the visibility of art from Syria becomes more urgent in this charged moment, Ayyam has announced the exhibition Wavering Hope, running from July 18th through September 5th, 2025, showcasing a broad array of practices, animated by the same question that guided this essay, wondering whether this tumultuous moment is the end of exile for Syrian artists or simply another chapter in a violent saga: “Yet even in this long-awaited moment, a deeper question surfaced: was this truly an end, or merely the next turn in a long cycle of hope and despair?”

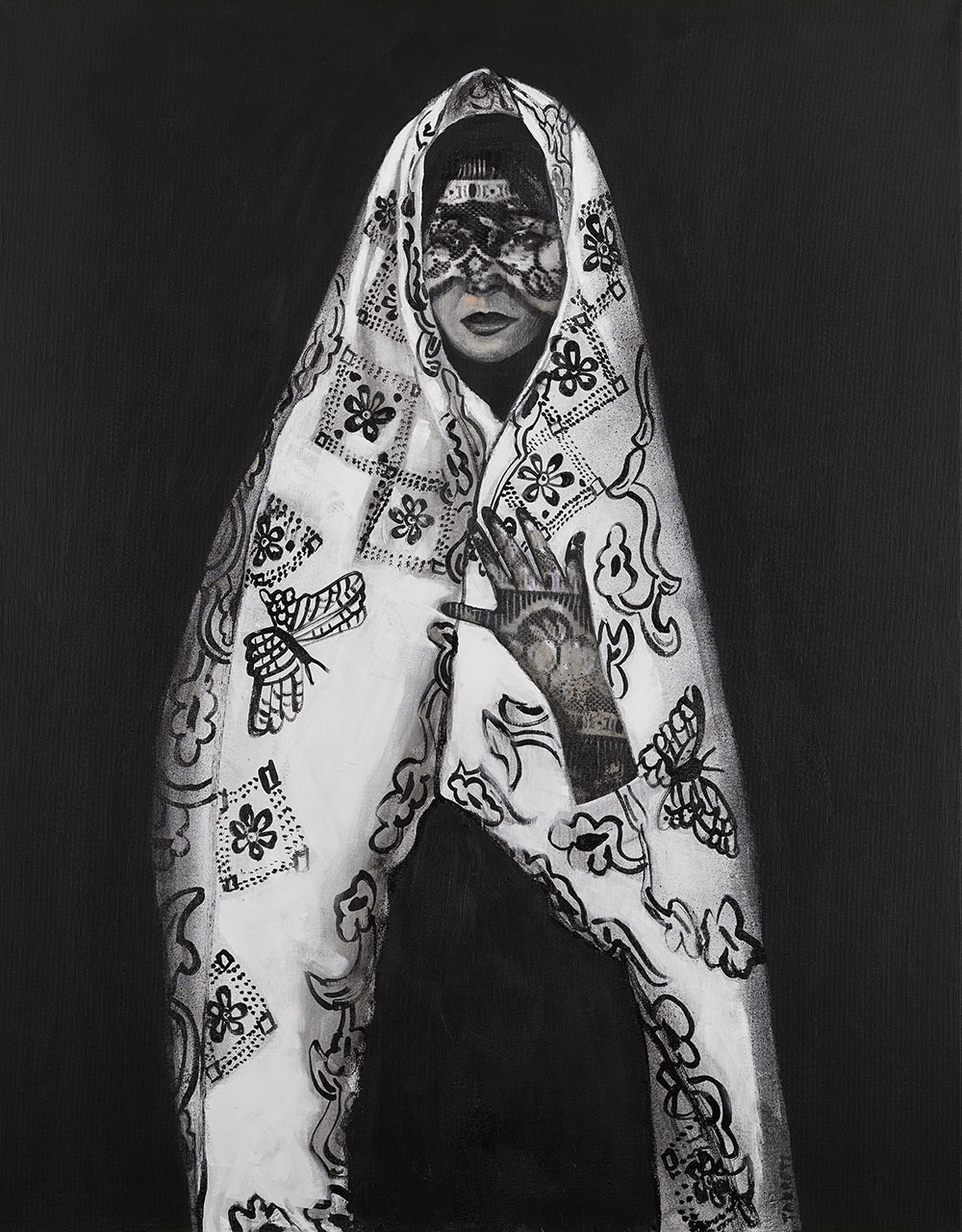

Well-known Syrian artists like Kais Salman or Khaled Takreti, whose works I had seen at Beirut’s Ayyam a decade ago, bring respectively, as Salman always does, an almost sculptural physicality of painting, depicting the sensory, political and emotional overwhelm of the present moment; and Takreti asks questions about how do we construct personal identity in the middle of such turbulence. Tammam Azzam is one of the most prominent Syrian artists from the revolution years, made famous for his photoshopped Klimt’s “The Kiss” against the background of a derelict Syrian building. His 2013 piece in the show, “Damascus” from the just as iconic Bon Voyage Series, also shows a destroyed home, this time flying away in balloons, with powerful resonance for Syrians who nowadays wonder whether it’s time to return home. His acrylic painting, “Storeys Series,” looks at a home that has been bloodied and sullied and can no longer be recognized.

Also based in Dubai is one of the main stakeholders in the field of Syrian art, the Atassi Foundation, established in 2016, to give art from Syria an institutional face. It was born out of a gallery founded in Homs in the 1980s by sisters Mouna and Mayla Atassi, that then became separate galleries in Damascus and Dubai. Today the foundation holds a very significant collection of modern and contemporary Syrian art, and is very active not only with exhibitions (last week they opened the exhibition Tracing the Unseen: Landscapes of Memory and Metaphor, at Foundry Downtown in Dubai, with works by Walid El-Masri, Farouq Kondakji, Rida Hus Hus, and Omar Hamdi), but also through publications, scholarship and texts chronicling the poorly archived history of Syrian art, as well as via collaborations with other institutions. Its director, Shireen Atassi, confirmed my suspicion that artists are not returning: “I’m aware of a few artists that have returned for short visits, but as far as I know, none have made a permanent return. The situation remains volatile, and it’s still unclear what direction the current administration is taking.”

Atassi speaks about additional reasons for not returning: “After 15 years of displacement, many artists now have families established in the diaspora, with children in school and lives rooted elsewhere.” Christopher Foulkes tends to agree. “Many educated Syrians have been living in exile for a number of years,” he points out, “and are more likely than their less educated peers to have established lives in Europe, America or Turkey which could act as a pull factor to remain in those countries. If HTS remains true to the rhetoric around building an inclusive Syrian society over the coming months and years, specific policy actions to entice the return of cultural workers might not be needed.”

But the writing on the wall right now isn’t so good: Rationed electricity, sectarian violence, poor infrastructure and lack of opportunities. The question as to what it will take for artists to return to Syria, Atassi is keenly aware, cannot be answered with certainty, for it depends on many factors, tied also with the political facts on the ground around the reconstruction process. “We do know that UNESCO, the Aga Khan Development Network, Qatar, and other Gulf countries are supporting the rebuilding of cultural heritage,” she said. “But the broader ecosystem — museums, professional galleries, and collectors — is still lacking.” Foulkes believes that at the international level, direct engagement with HTS by agencies such as UNESCO would do much to allay the concerns of Syrian cultural workers. How this would look in practice remains to be seen, but UNESCO announced it is returning to the country after 14 years to support the rehabilitation of the National Museum of Damascus.

At the same time that funding is being made available for the reconstruction of Syria, heritage experts have expressed concerns about a dramatic increase in looting of antiquities, and according to the Antiquities Trafficking and Heritage Anthropology Research Project (ATHAR), which investigates the black market of antiquities on the Internet, nearly one third of the 1,500 Syrian cases it has reported since 2012, have taken place since December alone. The history of looting in Syria is long and complicated, with all parties — the Assad regime, Daesh, other Islamist groups, local treasure hunters, and European dealers — being complicit in the trade, for many years.

An interesting twist in the story, however, is not only that the International Council of Museums (ICOM) has sent out a concern note about the increase of looting in Syria at the end of June, but also that they are liaising directly with the Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums (DGAM) in Syria, for the return of archaeological artifacts to Syria, and DGAM recently attended a meeting at the French National Institute for Cultural Heritage, both of which could signal some limited cooperation between Sharaa’s government and international organizations. But on closer inspection, the situation is more complex and perhaps flexible than we’d like to believe: The executive director of the agency is still Muhammad Nazir Awad, who held the position under Assad since the late 2010s and likely enjoys friendly relations with the current government, given that he’s appeared in the media recently calling for unfreezing international funding for heritage management in Syria and to make the tourism sector viable again. An additional challenge is that the current laws for the forming of associations and nonprofits in Syria, are a confusing maze of arcane and unclear regulations, most of them dating back to the Assad era, ensuring total government oversight, and while other loose regulatory frameworks were shaped by the years of revolution in the north of the country, this transformation never reached Damascus.

The solutions found to address the question of heritage, however, can be pivotal for the entire arts and culture sector: As Foulkes explains, “much of the key cultural heritage in Syria dates back to the pre-Islamic era, such as the Mesopotamian, Assyrian, Hellenistic, Persian, Roman, and Byzantine worlds,” which might make HTS uncomfortable. Islamist groups have generally decried classical archaeology as a Western construct, and have set to destroy it in an anti-colonial manner, as early as the French Mandate. The Assad regime, like other authoritarian governments — such as Turkey, Egypt or Israel — envisions a propagandistic, totally historicized view of this long past, which ignores the discontinuities, interruptions, and erasures, and proposes their militarized, chauvinistic and fearful present, as the natural future of that grandiose past. This alternative will never work for HTS, but the need to enter into compromises with international organizations, mostly because there’s much funding involved — the restoration of Palmyra is an urgent task for the heritage community — might lead them to take more creative, pragmatic approaches that would involve other sectors of the arts and culture ecosystem. Only time will tell.

But between the time this article was completed and then edited for publication, there have been various reports of cultural destruction in the country, most recently the demolition of the martyrs statue at the Saadallah Al-Jabri Square in Aleppo, on the night of July 2, 2025.

The outburst of artistic activity in Damascus, however informal, still raises important questions about the need to have centralized institutions and funding bodies for contemporary culture, which often doesn’t enjoy the same institutional status as archaeology. The Ministry of Culture, under the tenure of Mohammed Yasin Saleh (which also oversees DGAM), has begun to take a more active role, not only in terms of sponsoring exhibitions and cultural activities, but also inviting archaeological missions to return to the country — so far there have been no takers, although archaeologists have visited the country to examine the state of certain sites. In the absence of anything that resembles a coherent policy, and with empty coffers, it is unlikely that there will be a sound revitalization of artistic life in Syria anytime soon. In the meantime, president al-Sharaa launched on July 3, a new national emblem for post-Assad Syria featuring a golden eagle with 3 stars. The launch of the new identity was marked with public celebrations throughout the country according to local press, in the grandiose style of the previous regime.

Yet however uncertain, it is also a moment pregnant with possibilities. Denmark-based writer, philosopher and translator Odai al-Zoubi traveled to Syria in the aftermath of HTS’ victory, and he experienced a rebirth of the public domain, where difficult conversations about recent history happened for the first time. There have emerged spaces of freedom in fields like theater, publishing, and performance, which gave him a glimmer of hope: “I think I am a kind of hesitant optimist, at least a bit more optimistic than my friends, but not a lot. What are the factors that will bring artists back to work in Syria? First of all, stability, if people feel secure, because it’s impossible to focus on art when you feel there’s still war.”

He continues, “But even if the country is safe, you still need freedom, and this is not very clear right now. In the first two or three months, I attended some lectures, and there was no censorship, you could talk about anything: culture, politics, books. But later on things became opaque. They’re really not sure what to do; they surely want to live with Islamic values, but they’re not sure to what extent. So we have to wait and see, we have to test them, and they have to test us. People in Syria now are trying many different things, and at some point it will have to become clear if this is going to be a harsh Islamic regime or if they’re going to allow a degree of freedom. In both cases, the situation needs to be clear and now we have only mixed signals. But we have to continue trying, to continue holding lectures, readings and exhibitions, and this has become possible now.”