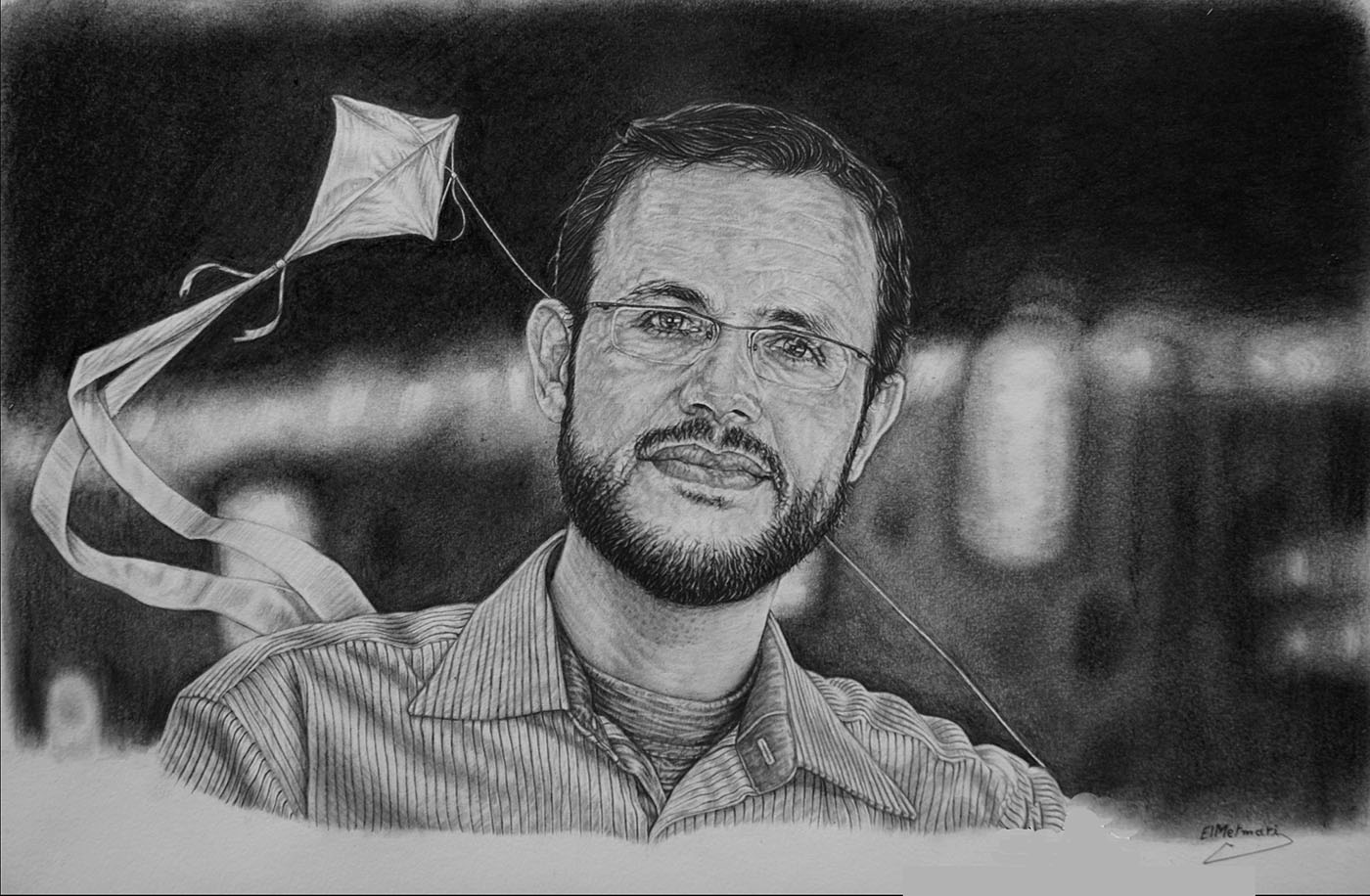

Dr. Refaat Al-Areer didn’t just teach literature, he was literature. He didn’t merely explain texts, he lived them, felt them, and transformed them into something deeply human, something fiercely Palestinian.

If I must die, let it bring hope, let it be a tale!

Taqwa Ahmed Al-Wawi

Some teachers leave the classroom at the end of the day, while others become the classroom itself. Dr. Refaat Al-Areer was the latter type — he didn’t just teach literature, he was literature. He didn’t merely explain texts, he lived them, felt them, and transformed them into something deeply human, something fiercely Palestinian. He didn’t ask his students to memorize, he asked them to remember. To remember their land, their stories, their strength. And even now, 18 months after Israel assassinated him, Gaza still whispers his name. He was an idea that never dies.

He founded the “We Are Not Numbers” project to allow Gaza’s voice to project beyond our confined geography. Because Gaza doesn’t need voices from the outside; it needs writers who write as though sirens emitting out of the dark. He believed in the power of simple details, and he knew that the world doesn’t need more statistics; it needs stories. Stories that hurt, pulse, and say: we were here. And we mattered. His work was to bring Gaza’s writers together with mentors from around the world who would help them tell the truth, expose atrocities, and resist erasure. The articles were not unfeeling reports, but testimonies of life. The project was not an academic activity, or a luxury, but a humanitarian movement powered by equal parts pain and determination.

Refaat Al-Areer was not just an academic. He was a living metaphor for Gaza’s steadfastness — no explanation needed because he made us feel the truth. In every word he said, there was resistance. In every line he wrote, there was pain, but never weakness. He turned sorrow into direction, oppression into paragraphs, and fear into speech that did not know fear. He turned words into stones, texts into weapons, and every student into a storyteller of justice. The bombs that ended his life failed to end his legacy — because what he planted in us continues to grow, still blooming under the dust and blood.

His teaching style was fiery, a flame passing from seat to seat, awakening minds and awakening a fierce awareness of their place in the world. Imagine being in a room with someone who doesn’t just teach the subject, but gives a new meaning to the very concept of learning. That’s what Dr. Refaat Al-Areer’s students repeatedly said. They weren’t talking about a regular professor, but about an experience that changed them from within. They said you didn’t leave his lecture with just notes, but with a burning spirit, a deeper sense of responsibility toward the world. Many of them say he changed their lives. And I believe them.

In my first year at university, I took Introduction to English Literature online, and the course professor asked us to follow Dr. Refaat Al-Areer’s lectures on YouTube. I was overjoyed, as if I had finally been given the chance to sit in his class, even if remotely. I memorized his words as one would memorize poetry, taking notes on his comments, listening carefully to his tone, to when his voice was steady, when he broke into joking, when he brought us back to seriousness. I would repeatedly send classmates clips of his videos. I quoted his words so often they jokingly started calling me “Taqwa, who memorizes Dr. Refaat Al-Areer’s every breath.”

I read everything he wrote. There is a kind of silent attachment that happens when you read someone’s work and get the feeling that their words were written specifically for you. I didn’t just read them, I lived them. I told myself: even if I didn’t sit in his lectures face-to-face, I would make him see me through my effort. He was a light that couldn’t be extinguished, and the proof is that when the Israelis assassinated him, he didn’t fade, but became a guiding star for anyone who wishes to tell Palestine’s story.

He wrote about Gaza like no one else. About homes that were bombed, memories that burned up along with all the other material of the house, of pain that couldn’t be spoken, only lived. Despite all that, he continued to counsel his students that “stories will remain, and they will bear witness.” What better testimony is there to this idea than his own life? He taught me, he taught all of us that stories don’t end with the death of their author.

The most practical lesson I learned from Dr. Refaat Al-Areer is: “When we write about martyrs, we must mention that the occupation killed them. We must not leave the verb in the passive.” This sentence wasn’t just a linguistic tip, it was a lesson in ethics, belonging, and struggle. He taught me that language is not neutral, and words can either expose crime or cover it up. How many times have I read headlines saying “A young man was killed in an airstrike,” without mentioning who killed him? Israel’s military occupation should never remain unknown. The occupation is the perpetrator, the killer, the one who turned Gaza into rubble, and the one who assassinated Refaat Al-Areer himself.

He always insisted that we must avoid the use of the passive voice, insisting that every action has an actor. For example, we should not say, “Gaza was left alone,” we should say, “The world abandoned Gaza.”

Dr. Refaat Al-Areer knew very well the power of language — how it can expose or hide, honor or betray. He didn’t want us to write like the world writes — in fear, in abstraction, in indifference. He wanted us to say clearly: they killed them. The occupation. The planes. The silence of the international community. The hands that funded, the mouths that justified, the leaders who shook hands over the rubble, smiling above graves. These are the killers.

He writes, “A house of four floors but thousands of stories is no more. The stories, however, will live to hear witness to the most brutally wild occupation the world has ever known.” When I read this, I couldn’t help but think of my grandfather’s house, also consisting of four floors, bombed by planes. My uncle and his children were inside, and they were all martyred. The house no longer exists, but their story remains, engraved in my memory as well as the memory of the city itself.

I believe that is a reason why our building was hit. We were helping people to live a “normal” life, despite Israel’s attempts to starve us and eliminate the possibility of living with dignity. Indeed, we are trying to live, just to live, but the occupation cannot tolerate that. Life itself is a crime in Gaza.

When he wrote about children, he was talking about people like me: “A Palestinian in Gaza born in 2008 has witnessed seven wars: 2008-2009, 2012, 2014, 2021, 2022, 2023A and 2023B.” I was born in 2006 and I lived through every war he talks about. I was only two years old in 2008, yet I remember everything — not with my mind, but in the very depths of my soul.

“In Gaza,” he wrote, “we often speak about wars in terms of academic degrees: a BA in wars, an MA in wars, and some might humorously refer to themselves as PhD candidates in wars.”

As the bombs fall and Israel targets sleeping families in their homes, parents are torn between several issues. Should we leave? But go where, when Israel targets evacuees on their way and targets the areas they evacuate to? Should we stay with relatives? Or should our relatives stay with us — whose home is relatively “safe?” We can never be sure. It’s been more than 75 years of brutal occupation — and over six major Israeli military onslaughts in the past 15 years — and we have so far failed to understand Israel’s brutality and mentality of death and destruction.”

I’ve lived this moment firsthand, repeatedly. I received news that my area had become a “danger zone.” Where do I go? No one knows. But we prefer to die in our home than to flee, because there is no place safe in Gaza.

He wrote about the difficult choices families are forced to make: “The big question Palestinian households debate is whether we should sleep in the same room so that when we die, we die together, or whether we should sleep in different rooms so some of us may survive. The answer is always that we need to sleep in the living room together. If we die, we die together. No one has to deal with the heartbreak.” This is the reality for every family in Gaza. We all sleep in the same room, to either die together or survive together.

He wrote about hunger: “No food. No water. No electricity. This 2023 war is different. Israel has intensified using hunger as a weapon. By completely besieging Gaza and cutting off the electricity and water supplies and not allowing aid or imports, Israel is not only putting Palestinians on a diet, but also starving them.” This is how we live. We eat little, drink little, and write a lot. Not because we have the luxury of time, but because we fight with words what we cannot fight with weapons.

And he wrote about the resilience that doesn’t end with a single life, but continues on into the community: “If I must die, you must live, to tell my story.” Oh, Refaat Al-Areer, you died, but you left us a thousand lifetime’s worth of words. We will keep telling your story, our story, the story of Gaza. Those words of his, quoted all over the world by people from all walks of life felt like his last will and testament, written for all of us who remain. He willed that we become the voice of those who are gone, of those who fell silent. To continue the story, not with sorrow, but with determination.

We carry his legacy in our pens. I keep his quotes pinned to my wall.

Dr. Refaat Al-Areer taught us to write about Gaza as if we are writing about humanity itself — raw, broken, beautiful, and unbreakable. He gave us permission to tell the truth, and tasked us with the responsibility to never stop telling it.

Everything he wrote was a mirror — no adornment, just painful honesty. He said what others dared not say. And that’s why the Israelis feared him. That’s why they killed him. But his voice, his words remain more alive than ever, echoing in his lectures, in his students, and in me. I never had the chance to be his student face-to-face, but I knew him as my teacher. I felt his spirit and understood his message. I, who once waited for the day I’d be one of his students in his classroom, now exist virtually in his presence. My exam is grief, and my degree is loss.

He taught me that literature is not a luxury, but a lifeline. That writing is not a cure, but a testimony. And above all, he taught me this:

If I must write, let it be with truth. If I must feel, let it be with fire. If I must live, let it be for those whose voices were stolen. And if I must die, let my words remain alive in the memory of time.