Victor Hugo’s way still guides those building bridges across languages, faiths, and histories in a time of fear.

“The human soul has still greater need of the ideal than of the real.

It is by the real that we exist, it is by the ideal that we live.”

—Victor Hugo

Yahia Lababidi

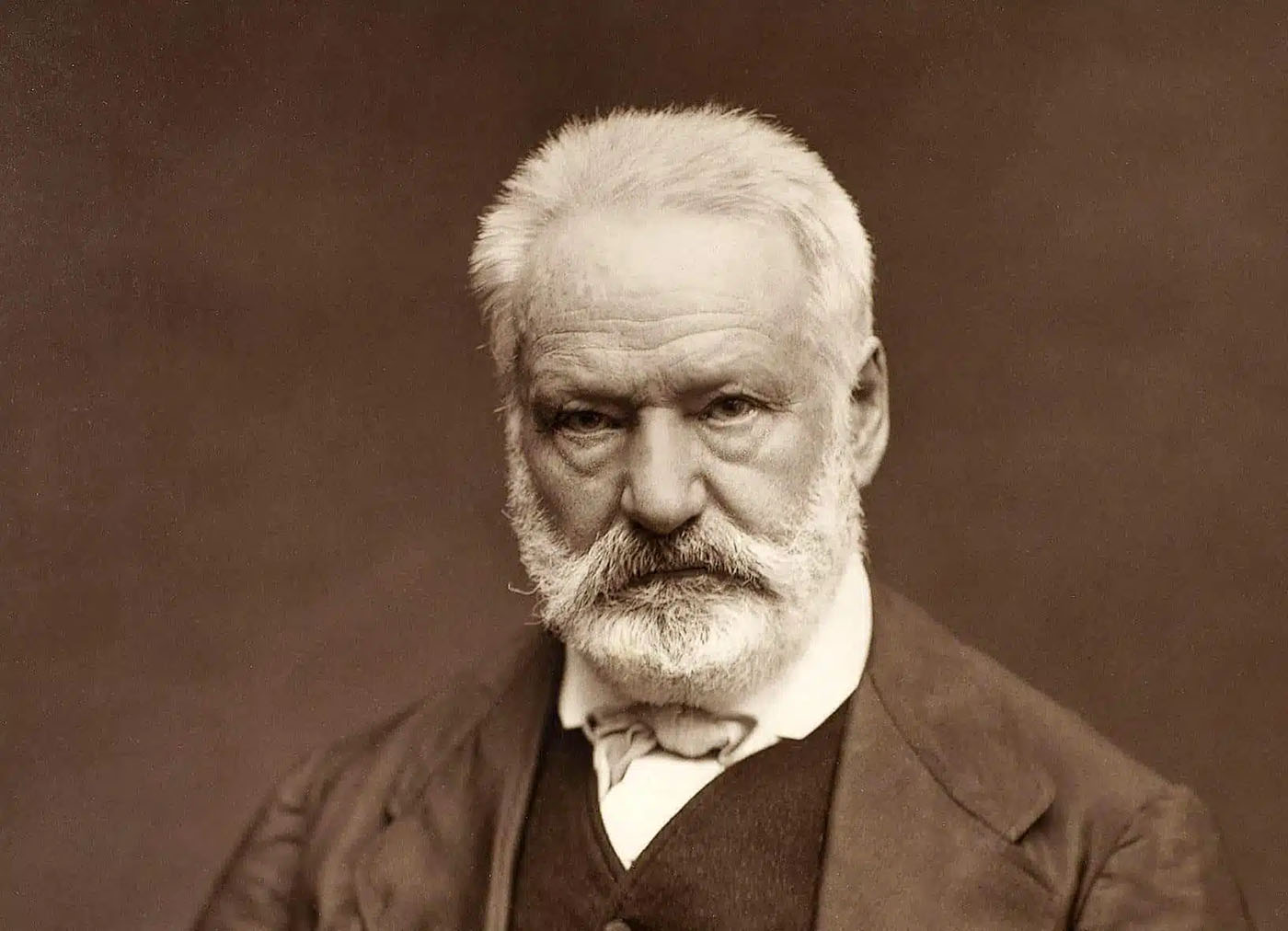

Victor Hugo belongs not only to France, but to the world. His imagination moved beyond borders, seeking conversation with distant ages and unfamiliar devotions. Wherever the sacred was voiced, he was drawn to listen. Among the lesser-known aspects of his spiritual life is a sincere engagement with Islam, shaped by reverence.

Hugo never converted, though speculation continues. Nor did he exoticize Islam, as many in his time were inclined to do. His relationship with the tradition unfolded slowly, through poetry and inward searching. That he looked to Islam for understanding in a climate of cultural suspicion speaks to his moral courage.

I first came to Hugo not through politics or history, but through poetry. In the wake of my own spiritual searching, shaped by an Islamic background and a longing for shared language across faiths, I was moved to discover in Hugo a voice attuned to the sacred beyond the bounds of his own tradition. It was in Les Orientales that I first encountered his verses touched by Quranic resonance — they felt less like appropriation and more like a reaching across. Later, in La Légende des siècles, his engagement deepened into something more sustained. This essay began in that spirit of listening.

What drew me further was how quietly radical this reaching felt. At a time when Islam was largely caricatured or cast as Other in European thought, Hugo resisted both dismissal and spectacle. He read with reverence. For someone like myself, who has often witnessed Islam misrepresented in public discourse, Hugo’s gentle attentiveness felt like an act of moral imagination. I wanted to understand how such a gesture was possible — and what it might mean for us now, in an age where faith is again politicized, and the space for sacred encounter feels diminished. In our current moment of rising Islamophobia, Hugo’s model of generous attention feels both urgent and instructive.

In La Légende des siècles, Hugo gave form to a spiritual epic spanning civilizations. Among its many episodes, those drawn from Islamic history have a distinct tone. His portrayal of the Prophet Muhammad in L’an IX de l’Hégire reveals a man poised in solitude before the weight of revelation. The language is muted, the mood contemplative. The overall sense is not critique or distance, but a desire to bear witness. What strikes me as a Muslim reader is how Hugo refuses the temptation to diminish or explain away the mystery of prophecy.

Elsewhere, in Le Cèdre, Hugo imagines a mystical exchange between the Caliph Omar and Saint John the Evangelist. A cedar tree crosses the desert, linking two faiths through vision. The poem resists the antagonisms of the age. In place of opposition, it offers a symbol of shared inheritance. Hugo’s words open space for affinity.

He returned again to Islamic scripture in a poem inspired by the surah Al-Zalzalah, The Earthquake. He approached it as one who had been changed by reading. These poems, scattered though they are, carry a through-line: he turned toward Islamic tradition with an open spirit, and he lingered there. He was not among those who viewed the East as an object of possession, seeking to define or to diminish. He read and absorbed what moved him. The Quran and Hadith appear in his work not as borrowed symbols, but as genuine lights. Where others tamed the unfamiliar, he let it remain radiant on its own terms.

The loss of Léopoldine, his beloved daughter, shattered him. From that grief, he emerged altered spiritually, more porous. In that state, sacred texts began to speak with new force. Among them, the Quran held his attention. He read it as a mourner seeking sustenance.

It was during this time that his interest in mystical thought also deepened. His explorations of the unseen, so easily dismissed today, were sincere. He was searching for contact with something enduring that could not be grasped. This impulse brought him closer to Sufi sensibilities, even if he did not name them. A longing for union, a reverence for silence, a desire to speak across separation — these threads run through his later work. In Les Misérables, written during this period of inner transformation, he observes: “The soul helps the body, and at certain moments raises it. It is the only bird that sustains its cage.”

In his reflection on Shakespeare, Hugo returns to the theme of universal divinity: “God has only one temple: the universe; only one altar: the earth; only one priest: humanity.” Such lines arise from study, sorrow, and a desire to find meaning where division had once ruled. The idiom may be Christian, but the vision resonates with Islamic metaphysics and its affirmation of unity — tawhid — which recognizes all creation as signs pointing toward one source.

Stories circulated that Hugo had embraced Islam, taking the name Abu Bakr. His writings do not confirm this. Still, the rumor persists, perhaps because the spirit of his engagement felt deeper than mere appreciation. It carried the profundity of belief, if not direct affiliation.

Instead of declaring allegiance, he listened deeply. That, in an age of shouting and conquest, was a radical act. In remaining himself while turning toward another faith, he unsettled those who expected sameness as the price of sympathy. His spiritual roots remained Christian, but they reached widely. To confine him to one lineage is to misread the soil from which his work grew.

Hugo’s reverence did not depend on a limited sense of belonging. In this, he joins the quiet company of spiritual humanists who honor the sacred wherever it appears. His engagement with Islam offered resistance to the imperial gaze. While others reduced Islamic civilization to threat or obstacle, Hugo affirmed its depth and grace. His poems became a gentle refusal of caricature. In them, he recognized beauty and moral order.

This stance was no exception in his life. He defended the condemned, poor and displaced. He spoke against tyranny, whether political or spiritual. Islam, for him, was part of the world’s sacred inheritance. In it, he saw a vocabulary of mercy and discipline. To understand Hugo’s connection to Islam, one must consider the whole arc of his vision. He imagined a future built on concord. His writing, his politics, his inward life all moved in that direction. His call for a “United States of Europe” belied a spiritual hope. He imagined sacred texts placed side by side, each illuminating the others. The Quran itself anticipates such a moment:

“We have made you into nations and tribes so that you may know one another.”—Quran 49:13

Hugo trusted that the Quran could speak beyond its historical audience, to any soul tuned to its frequency. That such a vision should emerge from the heart of 19th-century France remains remarkable.

His literary project was always expansive. What remains of this relationship? A few poems. A handful of lines. More deeply, a gesture. He turned toward what many turned from. He recognized nourishment in what others refused to taste. His legacy endures because he showed how to be moved by it without overstepping.

For those who hope to build bridges — across languages, faiths, histories — Hugo’s way still instructs. In a time when fear too often shapes our encounters with difference, his example offers another path. Poetry, deep reading, and the ability to glimpse the divine in unfamiliar form remain available to us, past divisive, narrow-hearted tribal allegiances. In his words: “It is by the real that we exist, it is by the ideal that we live.”