What is the capacity of words to communicate the unimaginable barbarism of Israeli settler-colonialism and genocide? How much trauma and catastrophe can a sentence hold? Might it be stronger, more resilient, than the concrete structures razed to the ground — or will it similarly buckle under the weight of 2,000-pound bombs?

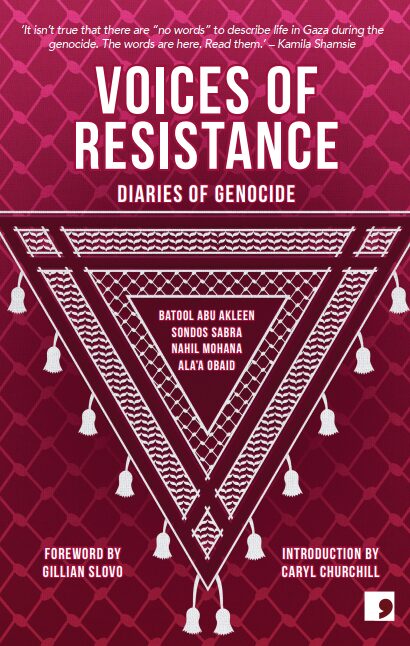

Voices of Resistance: Diaries of a Genocide

Batool Abu Akleen, Sondos Sabra, Nahil Mohana, and Ala’a Obaid

Comma Press 2025

ISBN 9781917093064

Francesca Vawdrey

Beshara Doumani’s observation in 2009 that “archive fever is spreading among Palestinians everywhere” could not be more relevant now. The 20 month-long and counting genocide and annihilation of cultural sites and public institutions in Gaza, alongside heightened settler-colonial violence and the mass internment and displacement of Palestinians in the West Bank, has rapidly accelerated the need to document and preserve.

It is within the context of this archival impulse that Voices of The Resistance: Diaries of a Genocide emerges, a collection of journals written by four Palestinian women writers, in response to the unfolding Israeli genocide in Gaza. The power of this collection lies in its diverse assemblage of voices, which sometimes depart and other times converge, illuminating the myriad perspectives and challenges of a people under attack. What unites these diaries is the unequivocal commitment to recording and sharing the Palestinian story.

First, we have Batool Abu Akleen, a 20-year-old poet and translator from Gaza City, who displays a cynical view of human nature and questions the function of literature in such times. Then Sondos Sabra, a 25-year-old translator and widely-published author, who embodies a more outward defiance that champions Palestinian resilience and the importance of popular memory. In addition, the diaries of Nahil Mohana, an established author and playwright, and Ala’a Obaid, a writer and coordinator at the Rasel Center for Creativity, cover the trials of motherhood under genocide; Mohana with dark wit and Obaid with the somberness of a woman giving birth during war.

Voices of Resistance deftly challenges the binary lens through which the Palestinian is typically portrayed, either as a terrorist or a “perfect victim.” The latter label denotes a Palestinian who is outspokenly critical of Hamas and opposed to all kinds of armed resistance; supportive of western intervention and inclined towards a general western sensibility; blessed with the noble skill of understanding “complexity,” and “nuance,” and the importance of “both sides”; grateful for each and every crumb of Israeli hospitality; and above all, penniless, pitiful, and defeated. The title of the collection itself allows the reader to view the Palestinian resistance through a more holistic lens, since these voices do not fit the Kalashnikov-wielding, balaclava-laden stereotype of the resistance fighter in popular culture, but rather a quieter, more typical form of everyday resistance.

Sabra brilliantly lampoons the oft-espoused lie that Israeli attacks on civilians are carried out for counter-terrorism purposes. She wryly observes, “Two days ago, on December 5, ‘terrorism’ was hiding in the body of Omar, my six-year-old nephew, perhaps in his heart, or maybe among his soft locks of hair. So they killed him,” highlighting the baseless absurdity of this excuse. Perhaps, she wonders, this “terrorism” might also be lurking “in the bells of churches” or “between the pages of books.” What else could explain the calculated destruction of three churches, including one of the oldest churches in the world (not to mention the 1109 mosques) and countless archives, libraries, and museums, in addition to the targeted bombing of every single university in Gaza and the destruction of over 95 percent of schools?

It is not just the tropes of victim/terrorist that the diarists unravel, but a third trope perpetuated by well-meaning liberals who are generally supportive of the Palestinian cause: the trope of the Untouchable Samid (which in Arabic means a person who is steadfast). Whilst typically not ill-intended, this stereotype is nevertheless harmful because it suggests an acceptance of the status quo; a heroization that, in elevating the Palestinian to the level of the super-human, ironically strips Palestinians of their status as humans that, like the rest of us, also succumb to fear, grief, and despair.

As Mohana reflects, “The genocide has not made me a superwoman … I’m still afraid of mice, and still I hate white beans.” This is echoed by Sabra, who writes: “Some have called me reckless, others: crazy. Only Yasmeen, my friend, has called me courageous. But none of these labels are quite true. I’m not reckless, not courageous. I am afraid, afraid to the bone.” Nothing sums up Palestinian fallibility and humanness better than this.

Abu Akleen witnesses the prevalence of another trait during the genocide, namely individualism, which she describes as the “truth of the human spirit.” Individualism is usually understood in a pejorative context, raising connotations of selfishness and greed that are antithetical to community and religion, associated with western capitalism and its obsession with unlimited “personal growth.”

However, Abu Akleen’s self-prescribed individualism is one that arises when a missile lands and “you smile because you are still alive, even though you know that another person was killed the very moment you realized you were safe”; individualism that occurs as “you rejoice when you realize that the home that was bombed wasn’t yours, but the one right behind it.” As the aroma of meat and onions fills her tent, she confesses: “I don’t feel guilty; I don’t worry that someone hungry might pass by and suffer.”

This is not individualism in the conventional sense, but the mark of an ordinary human being forced to endure extraordinary suffering. What this really shows is that starvation is beyond moral consideration. For Abu Akleen, “Survival is individual, always individual.”

At other points, community values and self-sacrifice triumph. As Obaid trawls the market in search of an egg — a luxury given the extreme inflation and scarcity of regular food items — an elderly man suddenly appears. Seeing her exasperation, he asks her why she is so desperate for an egg. She says it is for her daughter’s birthday cake. Touched by her story, “He slips into his small tent, and returns with a single egg.” He gives it to Obaid and tells her, “This is the last one I have … Happy Birthday to your daughter,” not knowing if and when he will find another.

Meanwhile, in the absence of cooking gas, neighbors club together to build ovens from scratch, using pebbles and sand, with a local baker to oversee the process. Apartments become impossibly overcrowded: 30 or more people to a room, as families rush to provide shelter. Two best friends share a bed, giggling and singing to eradicate each other’s fears, as one provides a home for the other. For Sabra, these moments serve as proof that “Gaza is not just what the war has destroyed; Gaza is the people who remind us every day that goodness still exists.”

These first-hand accounts attest to the collective will to preserve Palestinian memory at this critical juncture, in addition to providing invaluable evidence of Israeli war crimes. Sabra asserts, “The sting of memory is painful, yet essential to our survival, dear reader,” suggesting that, for her, the preservation of memory is existential. Sabra’s repetition of the phrase “I remember that I remember” calls upon the reader — whose attention is already sharpened through her earlier use of direct address — to participate in the act of witnessing.

Sabra positions herself as “strong and defiant against forgetfulness,” alluding to Mahmoud Darwish’s Dhakira lil-nisyan (Memory for Forgetfulness), a book-length prose poem composed in the aftermath of the 1982 Israeli invasion and siege of Beirut. Just as Ibrahim Muhawi writes that this invasion and siege was “an attempt to ensure a collective amnesia about Palestine,” Sabra writes: “They want to amputate my memory. They want to erase every trace of that life. But still, I remember.” This sentiment appears almost verbatim in Mohana’s account, signaling the diarists’ broader concern with Israel’s systematic attempts to erase not only Palestinian memory but the memory of Palestinian existence, a phenomenon known as “memoricide.”

The extreme constraints in Gaza inevitably impact the structure and language of the writers’ recollections. Sabra’s following account shows how trauma forecloses the possibility of neat prose: “My words have become clumsy and tangled. My thoughts appear in half-formed sentences, splintered by the overwhelming things I’ve seen and experienced.”

The syntactic breeziness in her description of life before the genocide — “streets full of life, the little shop on the corner whose owner would expertly fry falafel, its smell stirring the birds in my stomach” — sharply contrasts with the violent montage of subsequent memories that “accumulate” in the absence of space to process, or narrativize, each incident.

What are the ethics of writing in such times? For Abu Akleen, “Poems built from death can never bring pride; they can only bring more pain. My poetry is nothing but stylized pain.” Her shame at finding beauty in poems of suffering evokes Adorno’s famous statement that “to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” a comment on the insufficiency of language, or rather the barbarity of aesthetics, in a time of genocide.

He later retracted this view in his book Negative Dialectics (1966), where he argued that “perennial suffering has as much right to expression as the tortured have to scream,” foreshadowing Edward Said’s argument about the “permission to narrate,” that is, the Palestinian right to tell their story. Yet the current circumstances compel one to revisit Adorno’s initial remark. What is the capacity of words to communicate the unimaginable barbarism of Israeli settler-colonialism and genocide? How much trauma and catastrophe can a sentence hold? Might it be stronger, more resilient, than the concrete structures razed to the ground — or will it similarly buckle under the weight of 2,000-pound bombs?

Aside from discussing the ethics of her own writing, Abu Akleen considers the role of literary criticism in such times. She asks, “Who am I to tell someone being subjected to genocide that their pain isn’t well crafted, that their pain doesn’t seem authentic, that their pain isn’t painful enough?” In this she brings to mind Noor Hindi’s satirical poem, “Fuck Your Lecture on Craft, My People Are Dying.”

Huda Fakhreddine’s recent essay, “Notes from the Field of Arabic Literature in the Time of Genocide,” similarly considers how to analyze Palestinian literature whilst Palestinians “are being eradicated” en masse. Just as Gazans cannot be defined by their status as victims of war, “Palestinian literature is not [just] literature for times of crisis,” but part of a long tradition of storytelling in Arabic culture and society. The diaries should be read with this in mind.

The diarists’ use of intertextuality — or more simply, imbedded references or allusions to other literary texts — lends itself to this task. Mohana, whose diaries are replete with intertextuality, expresses concern around the fate of her house in al-Karameh that she and her daughter were forced to leave, “like the horse in Mahmoud Darwish’s poem.” This reference to “Ābadu al-Ṣubbār” (“The Eternity of the Cactus”) induces the feeling of estrangement that accompanies forced displacement. In the poem, the horse is left alone, because “houses die when their inhabitants leave.” What has become of Mohana’s home?

Mohana’s entries also point towards Arabic literature outside of Palestine. Her account “The Season of Returning from the North,” which marks the day that residents were permitted to return home after being forcibly displaced to the north, is a particularly illustrative example. This playful allusion to the Sudanese writer Tayeb Salih’s canonical Arabic postcolonial novel, Season of Migration to the North, helps to place the diary in dialogue with a broader Arabic literary culture, transporting readers far beyond the besieged enclave.

While each diarist provides a unique account of womanhood in Gaza through the war, with Mohana and Abu Akleen in particular highlighting the challenges young and/or unmarried women face, Obaid and Mohana are the only writers to address the trials of motherhood under attack. Here we see a determined Obaid, who is terrified of losing her unborn child due to the mounting risks during pregnancy in Gaza. This fear propels her to the south to seek shelter, despite the risk of being turned away (again). This risk is preferable to the alternative of staying, because “The bombing, the scent of gunpowder and the phosphorus hanging in the sky were threatening the life of the fetus growing inside me.”

The reader anxiously awaits the outcome of Obaid’s birth, wondering if and how she will succeed. She writes, with chilling brevity, “I am five months pregnant. The air smells of gas. And it feels like the baby inside me has stopped moving.” This stripped-back prose denies the reader any sense of comfort that would dilute the horror of the situation.

One morning, she wakes up with searing pain and the realization that she is going to give birth “as a displaced person.” At the hospital she gives birth standing up, unassisted, because there are no available beds. Her baby drops onto the floor, “screaming his first sounds in a war that takes away all the colors of life.”

Mohana’s recollections of motherhood are comparatively less visceral, though no less powerful. Whilst she similarly experiences a near-death experience with her daughter, as they dodge “shells and artillery fire … raining through the window and penetrating the walls,” her primary struggle is that of negotiating motherhood as a single parent. She criticizes how her community “still cannot accept the idea of a woman living without a man, and still actively punishes those who abandon married life, as if their loneliness and exhaustion in facing all this hell isn’t punishment enough,” highlighting the additional pressures she faces as a result of her marital status.

These diaries exist as a result of careful translation. While Sabra wrote her diary directly into English, Obaid wrote hers in Arabic — by hand — before translating it herself. Mohana and Akleen similarly wrote theirs entirely in Arabic, after which they were translated. These diaries were also edited and reformatted for readability. This is of course not unusual for published diaries, but worth noting. A diary written with an audience in mind is different to one produced solely for oneself — especially if the audience is from a different demographic than the writer. One should therefore be weary of treating these diaries as “raw material.”

These entries are also excerpts from larger records, begging the question of what is left out and why. For Arabic speakers interested in the burgeoning Palestinian archive, a sequel of untranslated, unedited diaries would be a welcome treasure. Until then, Voices of Resistance stands as a vital work of testimonial literature that refuses to be forgotten.