My Favorite Cake (Keyke mahboobe man) is a coproduction of Iran/France/Sweden/Germany, and is directed by Maryam Moghaddam & Behtash Sanaeeha. It opens in theatres in Europe in February, and in limited VOD. The film has been at festivals and won several awards, including Berlin 2024 (Competition) - International Critics' Prize & Ecumenical Jury Prize; Cabourg, Romantic Days 2024 (Competition) - Grand Jury Prize; Pass Culture 2024 - Young People's Favourite Award; Festival 2 Cinéma des Valenciennes - Revelation Award & Critics' Award; and the Montreuil Film Festival Audience Award.

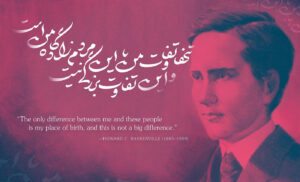

Sitting in a cinema and watching a film is a geographical and temporal journey that, through its images, language or structure, conveys the spirit of a place or time. My Favorite Cake by Maryam Moghaddam and Behtash Sanaeeha, takes us to Tehran, a filmmakers’ pandemonium where, paradoxically, cinema is a permanent antidote to theocracy.

My Favorite Cake conveys the story of Mahin, a 70-year-old woman who endures her loneliness with humor and fatalism, despite the support of her friends (divorcées or widows like her), and Faramarz, a cab driver of the same age, who is also making progress on the road ahead without anyone in his life.

Mahin and Faramarz build a story of their own, one that will have no reality anywhere else, at any other time, for anyone else. Their relationship is an act of pure subversion.

How, in today’s repressive Iran, can a love story be born from this encounter? How, at an age when you think the adventure is over, can a story begin? To do this, they need time, but Mahin and Faramarz don’t have much. They also need space, but Tehran is a city that is patrolled by the morality police, who prowl the streets, parks and shops, prepared to harass women and punish lovers.

What the film creates, then, is a space-time continuum in which Mahin is the instigator and mistress of the game, and in which she enrolls Faramarz, surprised and happy, since he had long since given up feeling the slightest hope he would ever be in love again. The action is almost entirely relegated to Mahin’s house, where the film takes in the space of a single night.

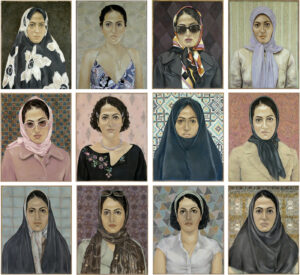

If My Favorite Cake starts out as a comedy of manners, it quickly evolves into a romance and finally grabs us, ending deep and dark, something we hadn’t suspected in the opening sequences. Watching this film, you get the feeling that co-directors Maryam Moghaddam and Behtash Sanaeeha wanted to paint a portrait of today’s Iran in small strokes, without resorting to caricature. Through the eyes of their two protagonists (with Mahin as the main character), they describe an Iranian society that functions in reverse, where values are antagonistic to their opposite: day versus night, outside versus inside, private versus public.

Night is the temporality of all possibilities, while day is subject to the hypocritical game that every Iranian seems to play by coercion. The exterior is shown in its everyday banality, but a walk in a park is transformed into a scene of arbitrariness when the morality police harass two young women who are not wearing the veil “correctly.” The violence of this intervention shows just what kind of collective neurosis the intrusion of politics into intimacy can create in this country.

We might think that the home is the only place of safety, but here again, the film puts things into perspective by showing us, at nightfall, the disturbing intervention of Mahin’s neighbor, a possible spy for the regime, blurring the boundary between the private and the public. Thus, we understand that even the intimate sphere is partly under control in the country of the Islamic revolution, a society infantilized by the religious powers that consider its citizens immature (especially women), and monitor them to ensure they don’t make a mess. It is in this hostile context that the relationship between Mahin and Faramarz must find its place.

Throughout the film, the directors raise the question of sex without representing it. There are several reasons for this. First, the age of the characters. At 70, desire is no longer expressed in the terms of youth. The relationship to the body changes, as does the relationship to physical pleasure: sex occupies a special place, and it’s easy to appreciate Mahin’s modesty and Faramarz’s tenderness. But My Favorite Cake also makes us feel how intrusive the state religion is, which has made sex taboo and invisible, to the point of impossibility. As a result, food and alcohol are the pleasures in which Mahin and Faramarz indulge together.

Certainly, life is possible in Iran, and a certain quietude prevails in the outdoor scenes (notably when Mahin goes shopping at the supermarket). But life is also possible in the barrios of Caracas, on the lagoon of Lagos or under the freeway at Porte de la Chapelle. The question is, what is the value of this life when it is subjected to these particular conditions, in this case, to frequent surveillance?

In Iran, freedom is within, the threat comes from without, from those who are supposed to protect us. This is why the film builds a world of its own, confined to the meeting of the two protagonists. Complicit in their desire (like the two directors), Mahin and Faramarz decide to focus on the beauty of things despite everything that works against them (their age, preconceived ideas, danger, surveillance, religion), and to firmly believe in it. From that moment on, a great sensuality is born between this man and this woman. All their senses awaken from a long torpor.

The spectator is made a privileged witness to their subtle game of seduction, to the rebirth of joy, and participates in the agape through the fluid movement of a camera carried in long sequences that draw us into their dance, into their song, into the delight of the moment.

Of course, sometimes we don’t really believe it. There’s a scene that’s a little overdone, dialogue that’s a little flat or an expression that’s a little forced. Sometimes, a slightly affected situation verges on the mawkish.

We feel a little embarrassed by their clumsiness too.

But we cling to their story because, like them, we feel that this is the last chance, the last opportunity, the one that won’t come again and that we don’t want to let go. We’d hate ourselves so much. Like Mahin and Faramarz, we pretend to believe, close our eyes and dance in spite of the pain, in spite of the shortness of breath. We take another glass of wine, letting ourselves be overcome by the intoxication that makes us light, that lets us hope for what no one hopes for in us anymore, even though we know it’s forbidden, that it’s a sin.

Tonight, everything begins again and everything ends. We enjoy the moment, the unforeseen offered to us one last time, we don’t care about politics or religion. We enjoy this chance as if it were a fantasy, a dream that can and will disappear. We know this because it’s the natural order of things.

This urgency to believe, even if it means flirting with the limits of reality and fantasy, is evident in one of the film’s most beautiful scenes. Faramarz, drunk with wine and desire for Mahin, catches his breath as he looks at a photo hanging on the wall. A memento. For a fraction of a second, he becomes confused, believing he has really experienced this moment, which belongs only to Mahin’s past. As if they’d always lived together, as if they had a common past…

Here, we know that a bond has been created between them that has become unbreakable.

What My Favorite Cake tells us is that freedom is built first and foremost by individual women. It’s a woman who takes the freedom and crazy risk of inviting an unknown man into her home. It’s a woman who transgresses the iniquitous law of men, cautiously but determined to cross the red lines their power imposes.

From sequence to sequence, from dialogue to situation, Mahin draws the man, Faramarz, into his desire, and together they invent the relationship of a lifetime, together they free themselves from the laws that religious politics imposes on their bodies and minds: Michel Foucault called this “biopolitics.”

The liberation we witness on the big screen is indeed political. Its politics brought back into the realm of the private, the intimate. The visibly cinephile Iranian authorities made no mistake in confiscating their passports and banning Maryam Moghaddam and Behtash Sanaeeha from accompanying their film to Berlinale 2024, where they were awarded the Ecumenical Jury Prize and the Fipresci Jury Prize.

But the absurdity of the sanctions is total, because in my opinion, My Favorite Cake is a deeply religious film. The title is proof of this. Without divulging the end of the film, we can say that the favorite cake, the best cake, the one Mahin bakes for Faramarz, is the one we’ll never eat, the one we’ll save for afterwards, when the time comes to enjoy it, freed from everything. Thus, the allusion to an epiphany of the “after” refers to faith in a God, or at any rate in transcendence.

Mahin’s home is an ideal world where anything is possible. Mahin and Faramarz build a story of their own, one that will have no reality anywhere else, at any other time, for anyone else. Their relationship is an act of pure subversion.

That’s the beauty of this film and its utopia: to witness the birth of a world through the desire of the characters and for them alone, for the eternity of a single night.