Even though it was released at the height of the Olympic Games in Paris this summer, Tatami is neither a documentary about judo, nor a fiction about sport, but if you expect Tatami to be a political film, you won’t be disappointed.

The place where politics meets sport is in combat, and in Guy Nattiv and Zar Amir Ebrahimi’s feature, an American-Georgian production, there are fights on multiple levels. The political battle (against authoritarianism and sectarianism), the sporting battle (for victory in the world championship), the inner battle (for a woman’s emancipation and freedom). These three levels of conflict are skillfully interwoven to create exponential tension and suspense.

The fact that Tatami is the first feature film to be co-directed by an Iranian and an Israeli filmmaker adds another level of suspense for the informed viewer.

The film’s intense black and white accentuates the Manicheanism of the situations and the drama of the subject. We’re reminded of Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull (1980), both in the choreography of the fights and their repetition, and in the stylized aesthetics of the set (no bleachers, no audience, artificial flashes, symmetrical framing).

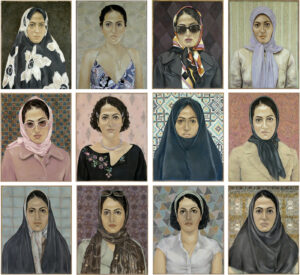

Leila Hosseini is a judoka representing Iran at the World Judo Championships in Tbilisi, Georgia. She is not a favorite, but believes in her chances. Maryam, her loyal coach, is herself a former champion who had to give up her career after (we’re told) an accident during an official match. The film focuses on the day of the competition, during which Hosseini fights and (as we hoped) wins.

As Leila triumphantly approaches in the upper frame for her next match, Coach Maryam abruptly receives an order to abandon the competition: the Iranian authorities refuse to allow her athlete to face the Israeli champion, who also has a great chance of going far in the competition: Leila has to fold.

The first sequence of the film shows Leila entering the stadium, hyper combative, and before starting her preparation, she chats in English with Israeli judoka Shani Lavi. The two women seem to know each other well, having previously taken part in the same tournaments. They respect each other, far from geopolitical considerations. It’s not hard to imagine a close friendship between these two women, who have everything in common — their sporting ambitions and, above all, the sectarianism of their governments. But politics being what it is, war is pulverizing the Middle East.

The film’s strength lies in the fact that politics is shown to be monstrous. It crushes individuals, gnawed by the fear of an omnipotent power that manipulates and instrumentalizes them: Leila is manipulated by Maryam, her coach, Maryam by her sports director, the sports director by the president of the federation, himself by the minister of sports and so on, right up to the Supreme Guide, whoever he may be.

Yes, Leila could become Shani Lavi’s friend if this eventuality were not swept away by the perverse logic of men who cling to their deadly power like mussels to their rock (there is no doubt — I allow myself this digression into reality — that if the power of the countries of the Middle East really belonged to their peoples, peace would soon be signed).

Power and its abuse is a central theme in Tatami. Political (male?) power, which alienates and murders, contrasts with individual power, which is turned against no one, a vital force that fulfills its own desire, whatever the cost.

Of course, it’s no coincidence that Tatami is a women’s film. All the (positive) protagonists are women (except for Leila’s husband, who protects the child, and the sports doctor, who repairs the athlete). The evil forces, on the other hand, are men.

In a unity of place, action and time that reinforces the growing tension, the challenge for the young judoka is to free herself from the hold that men have over her body, to regain control of it and invent her own destiny. The stakes are clear from the very beginning of the film, before Hosseini’s first match, with a wide shot of the weighing room.

Here, Leila and Maryam appear before the judges, whose job it is to check that the judoka’s weight corresponds to her category.

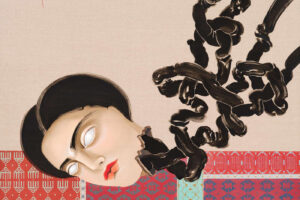

At a distance that prevents shamelessness, the camera films Leila undressing and stepping onto the scales. Nevertheless, Leila’s nudity gives rise to confusion, and in one shot the film transgresses what Muslim culture holds sacred. This shot confirms the filmmakers’ determination to tackle this issue, and the film can be seen from this moment on as a long process towards unveiling, the unveiling that a huge part of the Iranian population probably desires and that Leila will finally bring about.

In this sequence, Leila’s nudity is subversive. Leila’s body is itself a subversion of male law in Iran. Yet Leila’s nudity is not obscene, because it is not linked to sexuality. This is the great paradox of the Islamic veil, which artificially charges with a disorder what is almost never linked to sexuality. And even if Leila’s body is sometimes revealed in the intimacy of her couple and her family, during the judo championships in which she takes part, her body is only that of an athlete whose fragility, but also extreme resistance, concentrates all the questions:

Can a woman be naked?

Can a woman be strong?

Can a woman disobey?

Is a woman the owner of her own body?

At the weigh-in, Hosseini is three hundred grams over the weight limit and has just 20 minutes to lose it: even in her sport, Leila has no authority over her body, something she is unaware of at the start of the competition. She accepts the rules and follows them, engaging in a frantic cardio session under the authoritarian eyes of her trainer.

But as her chances of victory came up against the inflexible orders of those in power, these constraints became increasingly unacceptable to Leila. To the point of breaking away.

The film’s climax is subliminal. To catch her breath during her last fight, Leila removes the veil covering her head. It’s a gesture she makes unintentionally, unconsciously, naturally. To breathe.

The emotion is striking. With this simple gesture, we see all the struggles of Iranian women (and even beyond), all the promises of a new-found freedom, all the powerlessness of masculine force (state, religious, sporting, etc.) to alienate what for some women is natural. A light gesture in the face of all oppression. In this slow-motion shot, Nattiv and Ebrahimi’s film acquires its strongest metaphorical dimension and achieves its goal: no power can alienate a people without provoking a revolution, because all liberation is of the natural order.

Me pueden explicar porque no podían combatir? Cual era el problema político o cultural?