Fauda: the ultra-violent Israeli series lives up to its name while inventing ridiculous activity in Belgium and Lebanon, to the point that certain script details are really bad jokes.

Brett Kline

Season Four of Fauda begins with a series of bangs, in a bank robbery that goes bad in the northern West Bank city of Jenin. From the botched robbery emerges a rogue unit of the Preventive Security branch of the Palestine Authority, unknown to the branch director, involved in preparing large scale terrorist activities. That means missile attacks in Israel and targeted assassinations of Shin Bet figures, including the undercover Mistaaravim unit featured in the first three seasons of Fauda.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5JGCILhwWC0&ab_channel=FAUDAOfficial

Everyone is older and greyer now, and much beloved or hated characters such Doron, Captain Ayub, Nourit, Steve and Sagi are back in action, but on the Palestinian side, there are no familiar faces with which to identify. Much of the action in the 12 episodes takes place in Jenin, which is legitimate, as Jenin and nearby Nablus have spearheaded much of the violent revolt against the Israeli occupation for several years now, including organized and lone wolf attacks on both soldiers and civilians, often settlers.

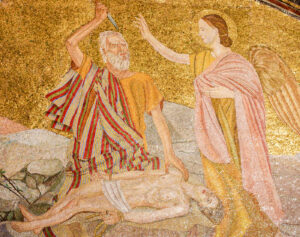

But in this season of Fauda (which means “chaos” and is used loosely by many Arabic speakers to mean a “mess,” or a “balagan” in Hebrew), the Jenin fighters are connected with Shiite Hezbollah fighters in Lebanon, through a group of radicals in Molenbeek, Belgium.

The Molenbeek suburb of Brussels drew worldwide attention in 2015 as the base of Islamic radicals who launched the wave of attacks in Paris on November 13th that year. More than 130 people were killed, including 90 at the Bataclan Theatre during a concert by an American heavy metal band. Those and other, earlier attacks such as at Charlie Hebdo Magazine and the HyperCacher food store in Paris, were carried out by Belgian-French-Moroccan terror cells, almost all young men with Belgian or French passports, in the name of Daesh, the Islamic State.

And this is where season four of Fauda begins to go off the rails…at the very beginning. More than 60 percent of all Molenbeek residents are Moroccan or of origin. Any connection they or anyone in Molenbeek has with Lebanon and the Hezbollah is most likely tenuous at best. And as any minor Middle East expert knows, the Hezbollah are Shiite fighters. They helped Alawite Syrian President Bachar al-Assad wipe out the Sunni Daesh radicals, bombing into ruins whatever part of his country Daesh had not already destroyed.

So how and why did Fauda creators decide to link all this on-screen Hezbollah-Palestinian activity to this Belgian city, which has nothing to do with attacks against Israel? Were they seeking to jump on a European-wide bad publicity bandwagon, or were they profiting from the general ignorance of Netflix viewers?

In real life the Hezbollah does supply small quantities of weapons to Palestinians in Gaza and in the West Bank, but that supply chain has nothing to do with Belgium.

For some context, Fauda is currently the most streamed Netflix show in Lebanon and has made NF’s top ten list since its premiere on January 20 in countries such as Jordan, United Arab Emirates and Qatar, and a number of European countries, such as Czech Republic and Serbia. Belgium is not among them, neither is France.

But as one viewer explained, “Fauda is fiction, not a documentary. Most viewers don’t know the difference between Hezbollah and Daesh, and could not care less anyway.”

He is certainly not wrong but he is…wrong. Fauda deals with burning hot subject matter, where the reality moves very quickly and often goes beyond any mere fiction. This is not a fantasy series — the real-life basis of Fauda, the Israel-Palestine conflict, often makes TV news three nights a week here in Paris. It is news even in the United States, where international conflicts often play second fiddle to car accidents and arrests gone wrong.

I believe that in some western countries, educated and uneducated people of almost all origins are fed up with news of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict after all these years. Without divulging the episode by episode action in the series, other than to say that the hyper realism of the shoot-out scenes is intense — and there are many of them — I do want to point out a few other scenes in which the details and dialogue are sloppily constructed, sometimes to the point of being bad jokes.

Just after the opening images, a rogue PA Preventive Security man in uniform is slashing to death a fellow rogue unit member in a PA holding cell in Jenin, allegedly for talking to the Israelis. This is his friend. But it would have been smarter to find out what he told them, if anything, rather than kill him. It makes the Palestinians look stupid and savage. At the same time, the Israelis are celebrating at a wedding party, with much singing in Arabic, dancing and drinking. The party looks like fun.

Israeli news presenter Lucy Ayoub, in real life born of a Christian Arab father and a Jewish mother, and brought up in both languages and cultures, plays Maya, an Israeli policewoman whose brother is a leading radical with the Hezbollah in Brussels and in Beirut. She makes an undercover drug buy in Ramle, Israel, of perhaps heroin or cocaine — we are never told what. Ramle and Lod are centers for wholesale and street level heroin dealing in Israel, entirely controlled by Arab crime families. There is little to no cocaine in Ramle. But most importantly, women are not involved in Arab crime family drug operations in Israel, or anywhere else. This is a man’s world. They can be users, yes, but not dealers. Hence, when one of the dealers remarks, “people will like buying from a woman,” it sounds pathetic and idiotic.

And missing from the table scene is a weapon — nobody sells weight to an unknown character without a loaded gun in view. To make matters worse, we later come to find that her mother lives in Ramle and that Maya herself grew up there. How can she be an undercover drug cop in her own small hometown — everybody knows her and her family? According to one well-informed US law enforcement source, nobody anywhere goes undercover in his or her hometown, certainly not in Ramle. This is a basic rule of the game. Note to Fauda teleplay writers: this is screenwriting 101.

In Episode Three (and this is a spoiler of sorts) with full knowledge that there are rogue members in his unit, the Jenin head of Preventive Security goes outside the city with only his driver, no accompanying vehicles as backup protection. When the driver suddenly stops the car and walks away, what do you think happens. Hmar — how stupid can the head of Preventive Security be? Fact is, this is impossible. He knows the only officials not out to get him are his Israeli contacts working in the occupied West Bank. He doesn’t go anywhere without a car in front and another following behind.

Then in Molenbeek, Mistaaravim unit “rave fav” Steve goes to make a drug buy in a huge housing complex, or at least to distract the tough guys guarding the steps. Doing what is known in some unpleasant circles as a junkie bop, nose running, dopesick with head and shoulders sliding up and down, he asks them, “I hear you guys have good things to smoke here.” Sure dude — something to smoke? All hash smokers walk like they are dope-sick. We believe you.

Then, right away there is yet another unintended comic moment during the intense shootout that follows. The head of the Belgian police unit, played by Laura Smet (daughter of famous French-Belgian rock legend Johnny Hallyday), announces on an open police communications channel, “The Israelis are taking fire.” That is a very indiscreet announcement, as if armed undercover Israelis invade Belgian housing complexes regularly, as if they even have the right to be there in the first place.

It gets sillier. With the housing complex completely surrounded by Belgian police, the Lebanese who allegedly run that part of the overwhelmingly Moroccan-North African complex (and I am doing my best not to give away the sequence of events) manage to move a bleeding, severely wounded Israeli fighter commando out of the building, drive him to an airport, put him on a small Falcon jet and fly him to Beirut, a four-hour flight, without even getting noticed, never mind getting caught.

You believe all this? If so, you are a real hmar, more so than the Belgians portrayed here. This is Hollywood claptrap for uninformed viewers, in my not-so-humble opinion, who cannot find Brussels or Beirut on a map. It is as if one writer who knows the background did a good job on the assault scene, and another one imagined the getaway while sitting in the Lalaland Café on Gordon Beach in Tel Aviv.

Next we have Shin Bet officials getting gunned down in their homes by Hezbollah-supported Palestinian fighters…highly improbable if not impossible. (My law enforcement source comments that after the kidnapping in Molenbeek, and potential ensuing leaks under torture, security officials in Israel would be under lockdown or close to it.)

There is a moment of comic reprieve, when the wives and children of the Israeli fighters (there are female fighters, as well) are taken to a kibbutz for protection (part of that lockdown). Surrounded by Shin Bet officials, one of the wives lights up a big fat joint and they all proceed to get stoned, determined to laugh their way through the drama. But the fun does not last long.

After explosions in Jenin in Episode 6, Jasmin from the undercover crew goes to hospital and at 16’58 in the script says “sba el kheyr, good morning.” Fair enough but she pronounces the “el” as “kchel” — a dead giveaway Israeli accent strong enough to get her killed. But somehow it got through the editing process. How many of you can hear the difference?

Next, there’s a road trip through Lebanon to get to someone who must be killed. The contact between Doron and Maya (Lior Raz and Lucy Ayoub) is well scripted at certain moments, with hints at intimacy between them. But as he has done successfully in the first three seasons of Fauda, Doron is posing as a Palestinian. In real life and on screen, Raz and Ayoub are fully bilingual Israelis. As such, they should be using occasional words in Hebrew, as educated real life Israeli Palestinians often do, but not here. And even without that, after an hour or two or three, she would begin to suspect, out of bilingual, bicultural instinct, that he ain’t the Arab he is supposed to be. Remember, she plays a cop…but somehow, it never occurs to her. And the success of this entire hair-brained mission through Lebanon is based on her incapacity to see through him. This is an insult to her bicultural intelligence.

And then the Jenin-based rogue unit launches some 20 missiles on Israeli cities for one day.

An Israeli security official comments, “it looks like Beirut in the 1980s.” One day of launching missiles and it looks like Beirut? How casual. How cheap. The missiles are deadly violent, yes, but the Israelis helped bomb parts of Beirut into the ground in the 1980s. This comparison is a supreme insult to the Lebanese. Find a sharp lawyer and sue the Fauda production company.

All these discrepancies have apparently not been caught by middle-of-the-road viewers in Europe and North America. They find the well-scripted, hyper-realist action scenes to be thrilling, and are clamoring for a fifth season. I guess ignorance is indeed bliss. There are far too many gaffes in the story for this season to pass muster, which is a shame.

Israel’s current government is dominated by far right, religious party ministers, and is de facto the most extreme right wing government in the history of the country. The reality on the ground in Jenin, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, the Gush Etzion roundabout on Route 60, Jericho, and who knows where next, is exploding. Civilians on both sides, but especially Palestinians, are being killed. Fauda scriptwriters did not have to invent a Molenbeek-Hezbollah-Israel connection, nor make a fool of a sympathetic Israeli Palestinian policewoman to compete with the reality. But they did.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)