There is a need to educate people about Imazighen’s evolution toward an inclusive definition of nationhood as an all-accepting shared space where all the elements of the identity spectrum cohere within a unity based on diversity.

Brahim El Guabli

Historians of the present, a branch of history that studies histories that are too close to the historian’s time, have developed a number of preventive measures for the study of unfolding histories. Primarily, awareness that whatever is unfolding in front of our eyes has to be contextualized in broader dynamics so that we might attain analytical depth. Developing critical distance from the subject matter in the absence of temporal distance that usually allows the historian to reconstruct and explain the past in an as-objective-manner-as-possible is crucial for anyone writing about histories whose relevance is still felt in the present moment.

Football, given the depth of the passions and emotions it stirs, is one of these historical topics that would benefit from the methodological insights of the historians of the present. Specifically for this essay, Morocco’s successful participation in the 2022 World Cup competition, organized by the Emirate of Qatar and FIFA, is an excellent case of the history of the present in action. The Moroccan team’s victories have triggered unprecedented debates about its Arabness and Afro-Amazighity, which, probed carefully, point to the deep changes shaping understanding around identity in the Middle East and Tamazgha (the broader Amazigh homeland of North Africa, extending from the Canary Islands to southwest Egypt, and including parts of sub-Saharan Africa) for the last 40 years. These debates signaled the obsolescence of the minority-vs-majority paradigm, revealing, in the meantime, Indigeneity as a challenge to the Arab-world-as-usual attitude that has dominated Arabic media and intellectual circles with regard to the existence of groups and communities that do not necessarily consider themselves Arab.

Whether the Moroccan football team (and the country by extension) is Afro-Amazigh or Arab was a question that thousands of Arab and Amazigh fans of the team debated and continue to debate since its phenomenal performance in the World Cup. Although not the immediate result of the championship, several factors gave this question an added dose of topicality in the stunning Qatar-hosted World Cup. For the first time in the team’s history, Moroccan players displayed their proactive Amazighitude (consciousness of their Amazighity), discombobulating the automatic assumption by many observers of their Arabness. Tamazight, the mother tongue of several players who grew up in Europe, gained unprecedented visibility throughout the world, fueling sharp discussions about the Arabness of a team whose players do not all speak Arabic.

The wider world learned about the Indigenous aspect of Moroccanness from the ubiquitous display of the Amazigh flag by the players and their supporters. Furthermore, the stadium guards’ confusion of the Amazigh flag with the LGBTQ one also helped bring media coverage to the tricolor symbol of Amazighity. In addition to several players’ Amazighitude, manager Walid Regragui articulated a forceful Africanist attitude by asserting throughout the competition that his team was playing for Morocco, the Maghreb, and Africa. Unlike any other team in Morocco’s football history, this one is particularly attuned to the overlap between politics, sports, and its own identity. Using the World Cup’s global stage to assert Amazighity within a larger Moroccanness, Arabness, and Africanity is new for the national team, and demands a more nuanced explanation than the facile rejection of Arabness some have given it. Instead of taking the team’s attitude as one of collective enmity toward Arabness, it behooves us to examine the long-term rise and dissemination of the Indigenous Amazigh consciousness, which the cliché-recycling Arabic media simply decided to ignore.

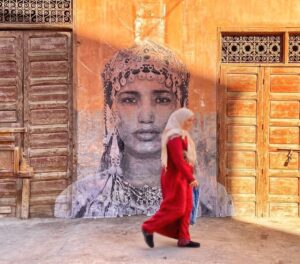

The deliberate reclamation of Amazighity and Africanity is just the latest indication of the cultural change that has taken place in Morocco (and Tamazgha by extension) since 1960s. In a matter of five decades, Morocco has witnessed a very strong, homegrown Amazigh Cultural Movement (AMC); Tamazight has been recognized as an official language since 2011; Moroccan street signs carry the visible markers of the re-Amazighization of the public sphere; and Africanness is lived every day as part of Morocco’s demographic make-up as a result of sub-Saharan African migration.

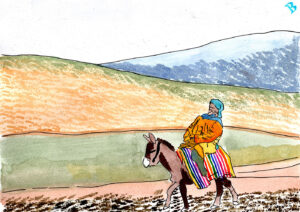

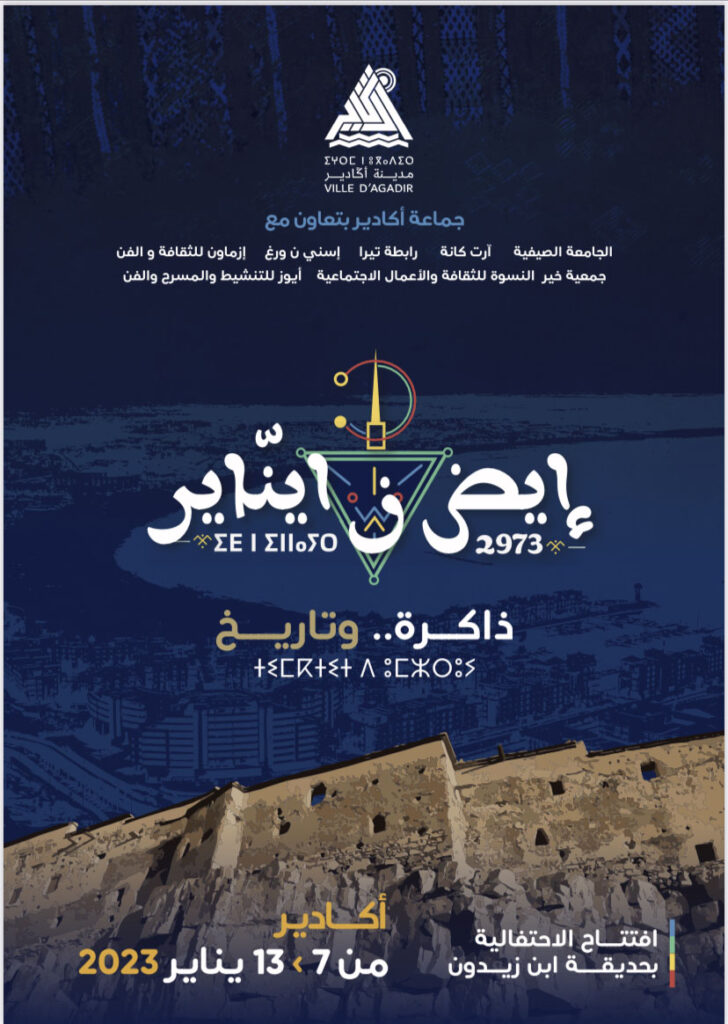

This week marks the 2,973rd Amazigh year. Imazighen celebrate this occasion, which is based on the agricultural calendar, by hanging olive branches outside the thresholds of their houses, cooking and exchanging vegetarian dishes, and daubing their animals with henna as a symbol of procreation and prosperity. Everything about the Iḍ n yennayer (January’s Eve) celebration, as it is called, is about connection to land and the cyclicality of time in Tamazgha, which they have inhabited continuously for at least 3,000 years. Since the 1990s, the celebration has acquired a political, mnemonic, and historical significance that is even deeper this year due to the debates about Morocco’s Arabness or Afro-Amazighity during the World Cup.

With tens of thousands of sub-Saharan African migrants living in the country, Morocco has become a destination for them rather than a steppingstone on their way to Europe. These migrants-cum-immigrants are changing and enriching Moroccan demographics, creating more awareness among Moroccans of Africanity and a concrete feeling of the country’s rootedness in Africa. Unlike the past, when Moroccan society gave primacy to Europe and the Middle East when it came to cultural and linguistic affinities, Africa is now present at the mosque, the grocery store, on the street, in the hospital and the school, and, for many households, even at home. The existence of an advanced human rights infrastructure and an assertive civil society has shifted public discourse about the rights of immigrants and helped make Moroccan society’s reckoning with racism and xenophobia deeper than that of its neighboring countries. Hence, the Afro-Amazighity the Moroccan players and their coach brought to the World Cup is a globalized manifestation of a new and transformative consciousness of their country’s Africanness and Amazighity, and a reflection of ongoing societal debates about Morocco’s plural identities.

The heated, and oftentimes unsavory, debates in social media over this issue essentially took place between two large camps. There was, on the one hand, the Afro-Amazigh camp, whose members believed that Morocco was playing for Imazighen (Indigenous Amazigh people) and Africans only, and, on the other hand, the trans-Arabist camp, which believed that Morocco was representing the entire Arabic-speaking world. Both camps were locked in a binary that failed to perceive and appreciate the richness of the languages, identities, cultures, and geographical locations represented by the team, turning the debate into an impoverishing duel that required the two camps to advance arguments to cancel each other out. It is understandable that many people involved in these debates in the strictly Arabic-speaking world are not necessarily attuned to intra-Moroccan discussions about identity and diversity and, more specifically, to the issue of Indigeneity and the critical approaches that undergird it.

Conceptions of Indigeneity and racial consciousness have become societal concerns in Morocco, distinguishing the Tamazghan context from the minority-based approaches (religious or else) that continue to predominate in the Middle East. Since the 1960s, Tamazghan civil society has worked tirelessly to undo the legacies of exclusion and erasure that were imposed on its people. Specifically, Indigeneity as the First People’s right to self-governance and resources was the beginning of a transformative discourse that went in tandem with cultural action, taking novel forms and shapes that fast changed mentalities and the public sphere. Nevertheless, Indigenous Imazighen’s attempts to assert their right to cultural and linguistic difference within a pluralistic, democratic homeland has not been acceptable to trans-Arabists (at least those who refuse to account for the existence of Indigenous people in places where Arabic is merely one of several spoken languages), including Moroccan trans-Arabists, who continue to call Morocco an Arab country. The clash of imaginaries between the two camps on social media is the result of the difference in the parameters of the debate between a sharp Indigeneity-infused discourse and an ahistorical imposition of an immutable Arabness on Tamazgha. The unacceptability of Afro-Amazighity to the proponents of trans-Arabism is particularly apparent in the resurfacing and purposeful use of the pejorative Arabic word barbar (Berbers) to diminish Imazighen, and which stirs up the latter’s historical resentment of the Arab invasion of their homeland in the eighth century.

These hypersensitive debates aside, Moroccans do not have to choose between their Amazighity, Africanness, Arabness, Blackness, Judaism, and Islam. Unlike its trans-Arab counterparts, the ACM has never envisioned Morocco as an Amazigh-only state. In fact, all the Amazigh literature regarding identity sought to shift the debate from the monolithic Arab-only identity, which contradicted the land’s history and sociology, to a multi-faceted identity within al-waḥda wa-al-tanawwu‘. “Unity in diversity” recognizes Amazighity as Morocco’s and Tamazgha’s primary identity without excluding any of the other components that contributed to the formation of this dialogic and multi-layered collective identity. From Brahim Akhiyyat’s al-Nahḍa al-amāzīghīyya (The Amazigh Renaissance) to Ali Siqi Azaykou’s Tārīkh al-maghrib aw al-ta’wīlāt al-mumkina (Moroccan History or its Possible Interpretations) to Mohammed Boudhan’s Fī al-hawiyya al-amāzīghīyya li-al-maghrib (On Morocco’s Amazigh Identity), Amazigh intellectuals complicated the imbrication of Indigeneity, history, and identity formation in Morocco. Hence, the Amazigh conception of Moroccanness, beyond any later isolationist and ethnonationalist uses, is first and foremost steeped in the recognition of its intertwined geographic, religious, linguistic, and historical roots, which defy its binary and exclusive constructions.

The failure of the Arabic media to portray the Moroccan team as an “Afro-Amazigh-Arab team” was a missed opportunity to stay abreast of Tamazghans’ growing and irreversible awareness of their Amazigh identity. Arabic-speaking media, including the official Moroccan television channels, also did not seize the opportunity to engage with the significance of Amazighitude for the larger geopolitical area of Tamazgha and the Middle East. The denial of Imazighen’s achievements in asserting their language and culture shifted the debate to social media, which, like every venue free of monitoring, turned the fluid and ambiguous issue of identity into an impenetrable binary.

The recognition of the fallacy of the Afro-Amazigh vs. Arab binary that played out in social media should not, however, be construed as a defense of the marginalization of Amazigh language, culture and identity. Tamazgha is and will remain Imazighen’s historical homeland, where they underwent and survived different colonizations in their long history. However, the Arab-Islamic invasion in the seventh century and the French colonization of the area in the 19th century have had dire consequences for Tamazgha. Imazighen embraced Islam, but the package also contained Arabic, which, for many Arabized Imazighen, replaced the Amazigh mother tongue. The shock of French colonization of Algeria in 1830 and the imposition of the Protectorate on Morocco in 1912 had an even deeper impact on Tamazghan societies, which, as a result, tightened their allegiance to Arabness, particularly since the middle of the 1930s. Thus, decolonization and nation-building centered Arabness and Islam at the expense of Tamazight and Imazighen. The ensuing Arabization of everything Amazigh created a surreal situation in which a people that has its own distinct language and traditions is subsumed under Arabness, which benefited from the full panoply of the state’s resources to supplant the land’s Indigenous identity. This insistent denial of Indigenous Imazighen’s right to their language and culture did not go unnoticed, creating much resentment among educated younger generations, who are now responding to exclusion by foregrounding their Afro-Amazighity.

The debate around the identity of the Moroccan team should thus be understood as part of this longer process of exclusion and denial of Tamazgha’s Amazighity. For the Imazighen who were involved in these heated discussions, the propensity of the Arabic media in Tamazgha and the Middle East to make blanket and unqualified statements about Morocco’s Arabness was déjà vu. It was the same strategy of erasure that they have been battling in their homeland since independence. Arabness, which is only part of the complex Tamazghan identity, has prevailed over the Indigenous language and culture of millions of Imazighen, who, for decades, were deprived of the right to speak for themselves in their own mother tongue. Those who participated in the heated online exchanges know that Morocco’s Arabness and Amazighity are irreversible, but the acrimonious nature of the discussion reflects Imazighen’s disappointment at the inability of the wider Arabic media to stay abreast of the transformative reforms that re-Indigenized Tamazgha. The recurrent references to the Moroccan team as an Arab team at the expense of its Amazighity radicalized Amazigh responses. As an example, Amadal Amazigh, or the Amazigh World newspaper, titled one of its issues “Imazighen Are Making African Glory in the Arab Homeland,” thus excluding Morocco from Arabness altogether.

If any lesson is to be learned from this debate, it is one of education. There is a need to educate people about Imazighen’s evolution toward an inclusive definition of nationhood as an all-accepting shared space where all the elements of the identity spectrum cohere within a unity based on diversity. Unfortunately, the Arabic media, for reasons that combine residues of Islamist and pan-Arabist ideologies, has remained faithful to the homogenizing discourse that for so long overlooked the cultural and linguistic richness that exists within this larger and interconnected space that extends from the Atlantic Ocean to Kurdistan. Imazighen’s bitterness and their forceful assertion of their Afro-Amazighity grew when the same media outlets distanced themselves from the defeat by France, describing it as the “Moroccan team” instead of the usual “Arab team” they used when it was winning. Adding insult to injury, some Arab influencers on social media simply dubbed it the loss of the “Berber team.” The takeaway here is that Imazighen have moved toward an Indigeneity-undergirded thinking about state, nation, and citizenship, but the world outside Tamazgha’s borders has yet to grasp the significance of the radical change this brought to conceptions of Morocco’s (and Tamazgha’s) identity on the wider stage. A pedagogical endeavor that builds on these heated discussions would provide a segue by which the Arabic language could better accept and accommodate Indigeneity as a transformative paradigm for a decolonized Arab futurity.

Imazighen have learned through their struggle for recognition that they are rooted in Africa. However, Africanness does not override Arabness, nor does it supersede any other aspect of Morocco’s multi-layered belonging to many spheres. The ACM’s founders in the 1960s did not embrace Léopold Sedar Senghor’s Negritude, but they never questioned their Africanness as a natural identity of all Moroccans. Their later construction of Tamazgha as the Amazigh homeland has deepened this Africanness further. These pioneers of Amazigh activism contested Arab nationalism, but they never rejected Arabness as a cornerstone of Moroccan identity. They themselves wrote in Arabic and belonged to predominantly Arabized institutions after independence. Instead of arguing for a unidimensional, impoverished Moroccan identity, they advocated Amazighitude: a critical, inclusive, and all-embracing conception of identity. It is this theoretical apparatus, which has been produced in the last fifty years of Amazigh Indigenous advocacy, that manifested itself during the World Cup. It simply became amplified because it played out before the eyes of the world through the assertion of the Moroccan team’s Afro-Amazighity.