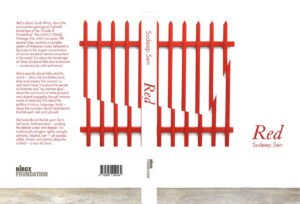

Deluge by Leila Chatti

Copper Canyon Press (2020)

ISBN: 9781556595899

India Hixon Radfar

I am waiting for the Tunisian American writer Leila Chatti to tell me, in her own words, in her debut collection of poetry, Deluge, about women in Islam, but she is telling me about blood instead. More and more blood. As the blood flows out of her, she tells me about it and I listen. “I keep mistaking blood for song,” the poet writes. But I do not like blood, do not like talking about it, have made sure never to write about it myself. I listen to her because it turns out she has gotten to know blood, she had to get to know it for a while, and she writes well about it. As for Islam and women’s place in it, traditional or modern, “I do not speak for God and He does not speak to me,” Chatti writes at first.

And then something changes and she is talking about Islam, and herself in Islam as I had hoped. I don’t know what that something is that has changed, but she has stopped talking about blood and is talking about women in Islam now. The subject is a desperate one and is as much about life and death as the blood was. The words flow out of her, flow past the flow of the blood, and I catch them and hold onto them.

In Islam, a woman cannot pray if she is bleeding. She also cannot hold onto the Qu’ran or open it. But for two years this poet bled without stopping, and now that she has stopped all that bleeding and lived, the prayers that she couldn’t pray before are now pouring out of her. What do you do with a prayer that cannot be prayed when you really need to pray it, when you might be dying of cancer, when your life depends on it?

You turn the prayer into a poem, and the blood into a poem, and death into a poem and your need to live instead of dying into a poem. And then you go back and write another poem about prayer, about blood, about the possibility of dying but of living instead, and soon the book gets written. The two years pass. For two years, she is a woman who cannot pray living with a man who is not her husband but loves her best, loves her better than God. Could that be? Loved her better than God when she could not pray to God and ask God to love her, ask God to help her. God sees all, but for two years she could not talk to Him, could not draw near to Him in prayer.

The other one holds her, bathes her, sleeps by her side, watches vigilantly for the flow of her blood, the blood flowing out of her, and I, as her reader, imagine him listening as well to the poems she forms with what is left inside of her. The love of this human partner, his tenderness, makes the poet weep. It makes the female reader weep, too. What can a woman say to that? What does a woman say to God when, for the two years that she is almost dying, He cannot be there for her? Cannot be or choses not to be? It is an important distinction. The poet is a little frightened of His presence and at the same time surprised at the man who does not want to leave her. Surprised and hopeful, as hopeful as it gets.

When she survives, she prays again. And this time she says of God, “And God knows best. If He calls a curse a blessing/ then so it is. And He said she was/ clean – she never knew a man. I’ve known a man but never a god/ that bled and lived. But I did.” Chatti is speaking here first as the Virgin Mary and then as herself. She does this sometimes. There are several poems in the collection entitled “Annunciation” which refer to the moment Miriam is told by the angel that she will have God’s child. “May it be done/ to me I said, and it was done/ so quickly.” Sometimes you can’t tell if it is Chatti or Mary speaking, or if they are one and the same.

You may be surprised to know, if you are not Muslim, that the only woman in the Qu’ran who has a name is Mary, the Prophet Miriam, the Virgin Mother. Be like her, she is pure, the poet was told as a child, told as all girls were told, and the poet believed that, too. But then the poet began to think, how can I be like her? I am a woman who loves a man and I have no son, I may never be able to have any children now. I am also no longer a virgin. And I bleed, I think I’ve bled too much, bled it all out of me.

The poet’s cancer is an unknown quantity behind her blood. And God is an unknown quantity behind her cancer, behind her life, behind her dying. Will he let her live? She writes another poem because she can’t pray now, is not allowed to pray. She sees another doctor because she can’t pray, and that doctor becomes another kind of god to her. Then she is taken care of for another day by the man who is better to her than God.

All this time the poet wonders if she is still acceptable to God. She wonders was she not acceptable because she had bled or because she had been with a man whom she had not yet married? Or maybe it was that she bled because she was with a man she had not married first and that is why God would not talk to her any more. It was not that she did not believe. All this time she had believed. It was not that.

In the end we do not know. We do not know why Miriam is so loved and why the rest of us women think that maybe we are not. We do not know why a woman can’t pray while she bleeds. But the poet has come back to us, thankfully, with all the questions still alive in her, and we welcome her back. The questions were there when she was a little girl, too, reading again and again that one sura in the Qu’ran. Any time she felt sad or like she did not know who she was, she read it, the sura, the verse in the Qu’ran about the Virgin Mary, and she identified with that other relatively young girl, the one that God Himself talked to and sent a baby to and entrusted to have his next prophet be also her son.

All the questions are back now but the poet is older and she had almost died but she has instead lived, and her questions are stronger now than they ever were before. Why, why, why… for a while she had felt like a rebel, distant, disowned, but it was not that she didn’t believe, she had never stopped believing. And here the poems pick up their tempo as Chatti further tries to understand her shame and the former pain, worrying also about some innocuous future pain and how it might have all been taught to her. “I don’t understand your distinctions,” she tells God about His role in her inner life. Towards the end of the collection, Chatti asks her beloved Miriam these questions in a poem entitled Questions Directed Toward the Idea of Mary: “Did you long for His touch or was suffering enough for you/ to know He was there?” and “Did your worship falter once you were sure you were good?” Truly the two identities, Chatti’s and Miriam’s, have merged. But Chatti is not always so positive about Miriam. At one point Chatti says only, “I cannot bring myself to resent her.”

Chatti’s poems come to this, I think: “I walk between miracle and confusion.” She answers some of our questions throughout, and the Notes at the end of the book answer others. Then there is an Acknowledgment that answers a few more, followed by an About the Author that answers many. For some reason, the book has waited a long time to tell its reader these things.

Chatti was only in her twenties when she started bleeding and did not stop. But she is recovered now. One thing is undeniable, Leila Chatti needs to keep writing, she needs to keep thinking about the subject of women in Islam because she will most certainly be able to help forge a new path forward for women in Islam. This new path will include a new kind of marriage, a new kind of prayer, a new kind of man and woman, a new kind of sisterhood and brotherhood, a new kind of respect. Some of this vision is already detailed by Chatti in Deluge, her tremendous new book of poems.. Islam can absolutely do this. It can see women as they are. It can name them. Thank you, Leila Chatti, for letting me see this. Thank you for your vision.