Select Other Languages French.

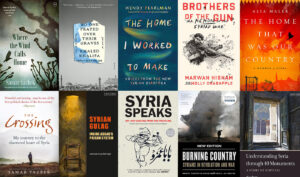

The titles on this reading list may not be unique in their portrayal of marginal characters and settings, but each one holds profound meaning for the writer. They offer insightful glimpses into lives lived at the edges of society, exploring the challenges, triumphs, and complexities of characters who invite readers to empathize with experiences often overlooked.

My friend Hamoud Saud dedicates his forthcoming collection, The Raven of Ruwi and Other Stories from Oman, to “the margins, the marginals, and the marginalized.” The fabulist work of this unconventional writer from the geographic and theological margins of the Arab world reflects his sense of living in intellectual exile. If it is part of morality not to be at home in one’s home, then Hamoud (like Adorno) is a most moral man, whose writing brims with figures of the sort Edward Said called marginals: exiles, expatriates, outcasts, rebels, the dispossessed — those outside the centers of power, inhabiting the hāmish, far from the markaz. The titles on this reading list are by no means simply unique in depicting marginal characters and settings, but each is as deeply meaningful to me as Hamoud’s book, which I picked up on a whim one weekend in Oman (my home for three years) and felt an instant compulsion to translate.

The Bitter Orange Tree, a novel by Jokha Alharthi

Jokha — who graciously agreed to write the foreword to Hamoud’s book — explores memory, grief, and belonging through the eyes of Zuhour, an Omani student in an unnamed British city, whose sense of alienation amid snow that never seems to stop falling took me back to my own freshman year as a foreign student in frigid New England. Haunted by memories of an ill-fated grandmother figure — an archetypical marginal — and unhealthily involved in her Pakistani roommate’s family drama, Zuhour struggles to adjust to her new life while coping with intense feelings of regret and nostalgia. The novel is not an easy read, with a fragmented structure that mirrors Zuhour’s memories, but Jokha’s trademark lyricism and Marilyn Booth’s elegant translation from Arabic make for a rewarding experience.

Twilight in Delhi, a novel by Ahmed Ali

First published in London in 1940, Twilight in Delhi is a haunting portrait of the city in the early twentieth century, depicting a declining subculture that became completely marginal after the Partition of India in 1947 and the largest population transfer in history (which included my grandparents). The novel follows the travails of a Muslim family, evoking a vanished society through imagery so vivid that you can almost hear the azaan ring out over the alleyways of Old Delhi: the frantic cries of pigeon- and kite-fliers, the scent of night-blooming jasmine, the amorous pursuits of rakish men, crises in the zenana, mansions that crumble even as a poetic culture is collapsing under the overwhelming violence of empire. (Bonus read: William Dalrymple’s excellent City of Djinns includes an interview with the author, by then a broken-hearted man exiled from his beloved Delhi.)

The Janissary Tree, a novel by Jason Goodwin

A detective novel set in Ottoman Constantinople, a work of historical fiction, a murder mystery, a Turkish cookbook, a period thriller: I often wonder how Jason Goodwin must have pitched this book. Goodwin — novelist, historian, travel writer — tells a seriously unputdownable story with a unique protagonist: Yashim, a eunuch detective and serious chef, whose place on society’s sexual margins gives him access to court politics and the imperial harem’s inner workings. (Bonus read: Yashim Cooks Istanbul includes many of the tasty Turkish recipes from the novel and its sequels.)

In Other Rooms, Other Wonders, stories by Daniyal Mueenuddin

What separates Mueenuddin’s collection from other, often pedestrian South Asian fiction in English — apart from the spectacular storytelling — is his casual self-assurance. A source of immense satisfaction for this Pakistani-American reader, these stories are not written exclusively for the white gaze. No spices or kitchen smells here, neither crowded bazaars nor riots of color, zero terrorists. Just an unflinching gaze at feudal life in Pakistan, with all its cruelties and small joys; at Chekhovian characters orbiting a large country estate; and at the complex linkages between Pakistan’s feudal elites and its marginalized rural poor.

Memory for Forgetfulness, by Mahmoud Darwish

Mahmoud Darwish reflects on war, exile, and coffee during the 1982 Siege of Beirut in this prose poem, skillfully translated by Ibrahim Muhawi. Part memoir, part essay, and completely heartbreaking, Memory for Forgetfulness documents a single day in Beirut under Israeli siege and bombardment, invoking the resilience of the human spirit and the power of language to rebel against utter marginalization. From pages upon pages of the most sensationally powerful imagery, two minor points remain curiously lodged in my memory: how deeply ʿAmm Mahmoud loved his coffee (“it is a meditation and a plunge into memories and the soul”); and his relationship with the Pakistani poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz — exiled from his homeland, living in Beirut during the siege — who has a walk-on role, asking Beirut’s artists to “draw this war on the walls of the city.”

The Rebel’s Silhouette: Selected Poems, by Faiz Ahmed Faiz

A tattered pocketbook of Faiz’s collected works has sat on my bedside table for over two decades. Agha Shahid Ali’s loving selection captures Faiz’s belief in ghazal as an act of defiance and love as a revolutionary force, whereby the Beloved of classical Urdu becomes indistinguishable from the homeland and the revolution. “That which was then ours, my love, / don’t ask me for that love again,” Faiz declares, for “there are other sorrows in this world, / comforts other than love” — that is to say, the revolution. Ali, who taught creative writing in Massachusetts, was himself a poet, deeply steeped in the literatures of both languages, an embodiment of Salman Rushdie’s assertion that “something can also be gained,” and is not always lost, in translation. If one is tempted by the sacrilege that Faiz can be improved upon, then it must be because of this couplet: “Don’t leave now that you’re here— / Stay. So the world may become like itself again.” (Bonus read: Ali blends the landscapes of Kashmir, another marginal land, and the American West in A Nostalgist’s Map of America.)