Art, as we’ve observed from Picasso’s “Guernica” and the works of Banksy, can be effectively engagé, bearing visual testament to the erasure of cultures and peoples…However, since October 7, how criminality is understood in the attempt to erase and re-inscribe is vital.

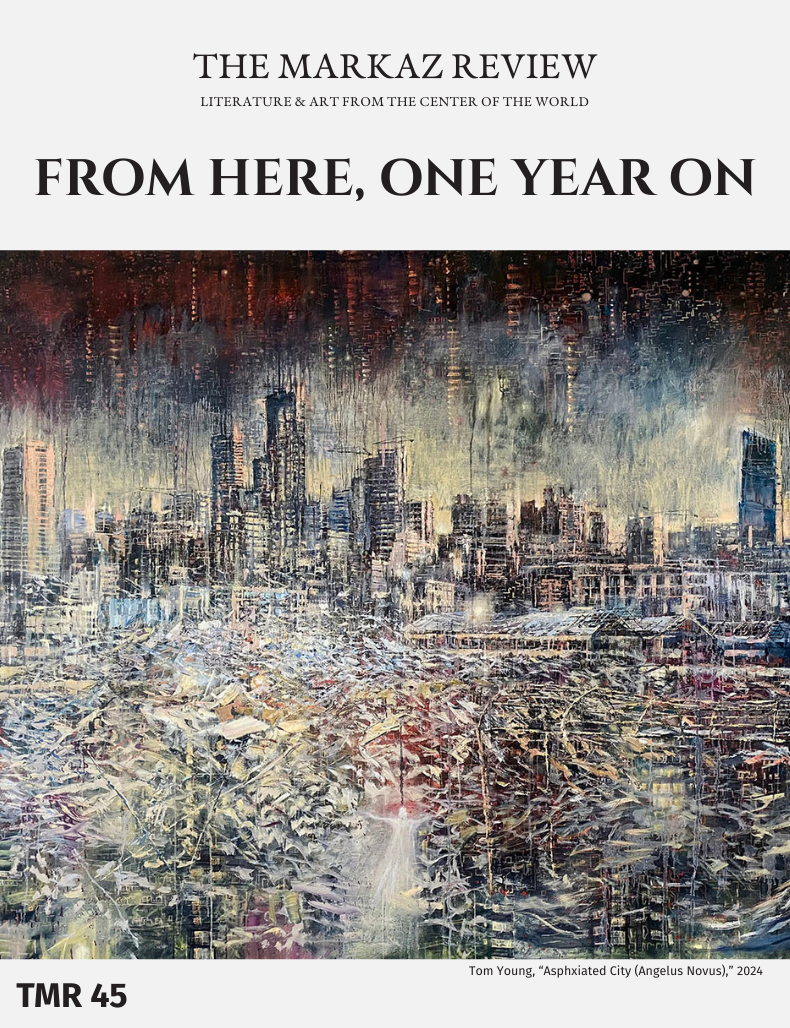

In a series of paintings done over the past 18 years, Tom Young’s canvases record ongoing catastrophe — occupation and violence against Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank, economic fallout and the August 4, 2020 port explosion in Lebanon, and poverty and civil war in Syria. Art, as we’ve observed from Picasso’s “Guernica” and the works of Banksy, can be effectively engagé, bearing visual testament to the erasure of cultures and peoples. Walter Benjamin, in his critical assessment of Paul Klee’s watercolor “Angelus Novus” (1920), stated that as winds would push an angel backwards into the future, his eyes and wingspan remain focused, framing the piling up of one catastrophe on top of another.

Recently, Arundhati Roy also made a searing comment on activist energies in a late-stage capitalist world, stating, “[t]he only moral thing” the current wretched of the earth “can do apparently is to die. The only legal thing the rest of us can do is to watch them die. And be silent. If not, we risk our scholarships, grants, lecture fees and livelihood.”

In Young’s ethically motivated art, the paintings are not only evidence of a previous stage of the Arab world’s catastrophe — that is, a present process still carrying the trace of its past unraveling — but also the later stages of a Dickensian witness to homeless children being made to walk on continuously without shelter, as the globalization of cities like Beirut swallow up its ever-increasing refugee populations, from Palestine or Syria. Whether it is the outstretched pull of global financial centers (once centers of empire themselves), the criminality of colonialism’s present, or the drive toward power pushing others into stateless exile, wretched invisibility and cruel injustice is marked in Young’s paintings.

It is difficult to suggest that there is one particular painting that begins to encapsulate the current catastrophe. However, since October 7th, how criminality is understood in the attempt to erase and re-inscribe is vital. “Criminal” (2009), selected for a contemporary art exhibition in Gaza City, had its first public viewing by way of a digital projection on a wall there. A secondary dimension of reality was forced on the actual painting since its physical delivery was stopped by Israel’s blockade.

In his essay, Walter Benjamin claimed that works like poster art were an example of a loss of aura. In his assessment, the impression one gets of an artwork is in its craft and the experience of seeing it “in real time” as opposed to seeing it in its virtual form. The display of “Criminal” in Gaza, virtually, is not simply the artwork in whatever form it comes, that is its presentation to the public. Its visibility as a copy-at-a-loss is a matter of the politics of aesthetics that prevents Gazans the right to view the way in which some artists, outside of Palestinian lived reality, have come to understand it. The virtual “Criminal,” as such, becomes a means by the Israeli state to prevent the Gazan population from seeing the growing international empathy to their plight and struggle against Israel’s colonial rule. The painting was eventually exhibited in 2024 at Beit Beirut Museum — itself, a battle-scarred former sniper’s nest in the heart of the Lebanese capital — and sold to raise funds for Dr. Ghassan Abu Sittah’s Children’s Fund.

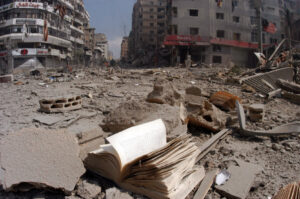

Still, “Criminal” stretches beyond any fixed historical situation. October 7th, in mainstream media, has been read as an unprovoked Palestinian act of aggression, failing to reference an illegal Zionist settler population occupying the land and homes of evicted Palestinians. Mainstream media, as a sector of Big Brother’s divested energies, forgets the history of colonialism’s force: when to start a story and to how to capture people’s minds within this framework. But when a people have been caged up for so long and made to suffer systemic violence, as well as periodic slaughter (the onslaughts of 2008-2009, 2012, 2014, 2021 and 2023-2024), any act of aggression can be seen as a colonized will not to die.

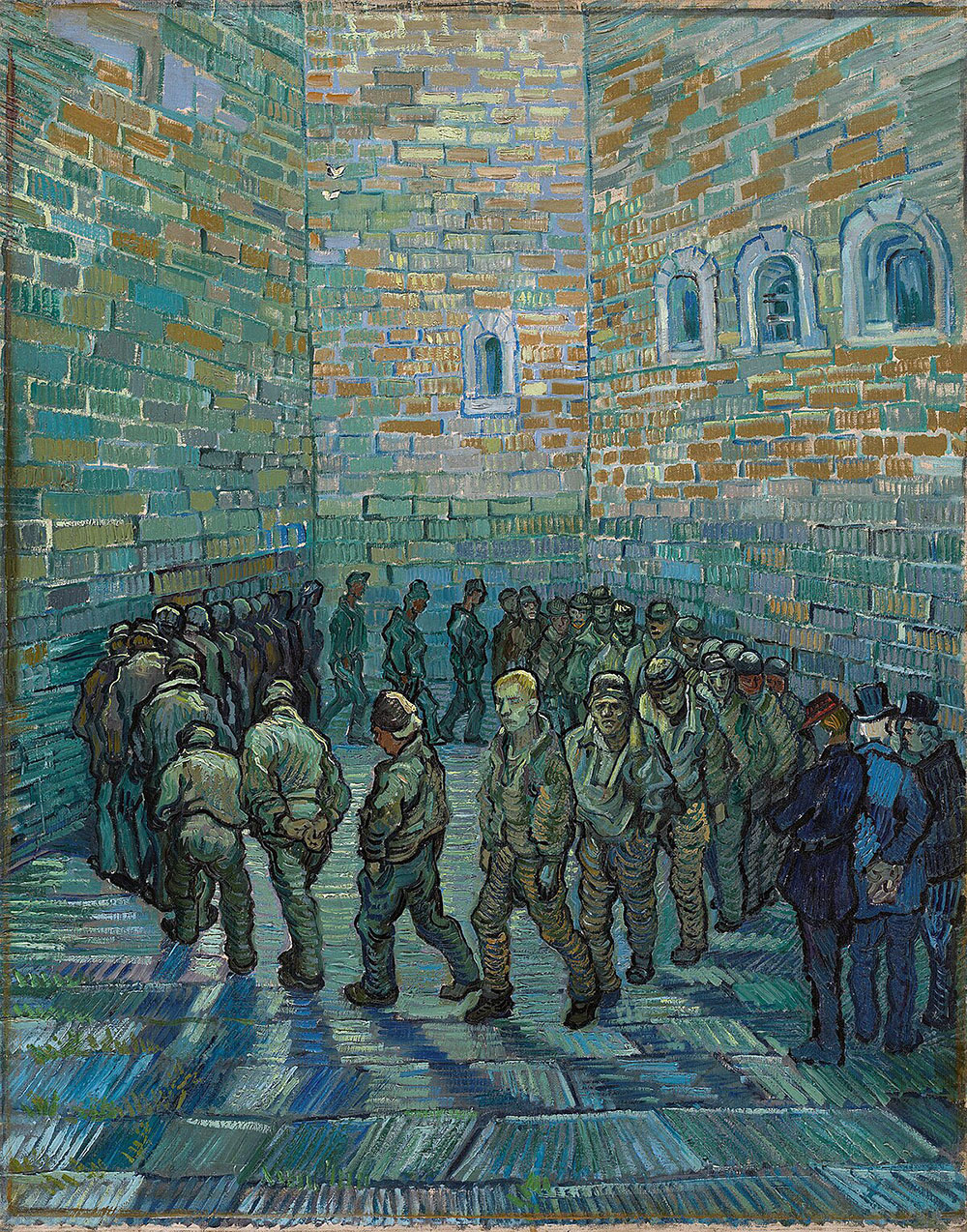

A predecessor of “Criminal” can be seen in Vincent Van Gogh’s “Prisoners Round (After Gustav Doré), 1890.” This painting, of a collective imprisoned population walking in a circle within a cell, has as its focal point an unidentified solitary man, head down seemingly walking aimlessly. The ground has been raised and covered over in cement as though a wall is beneath his and the others’ feet.

The prison seemingly bends under his movement. In the reading of this painting, to use the word “criminal” describing the inmate would seem absurd, as language fails or is made to appear satirical in the face of the painted reality. The walls around “the criminal” monitor his every move, presenting him from a panoptic angle.

If the contemporary presence of “Criminal” makes a satirical and absurd comment on how the individual tries to have agency in the power to name, then surely, “Innocent” (2023) presents a surreal depiction of human life under the rubble. Even today’s mainstream and, more critically, independent media, showcases how the Palestinians’ attempt to speak and represent themselves is gaining permissibility.

In Young’s vision, the boy (based on a 2008 sketch of a boy in East Jerusalem) seemingly comes out from under and over the rubble exhibited, as though he were in a newsreel or on TV, and shows himself. The question is under what circumstances or by whose permission. At the top of the painting, there are eerie rays of light, or rather the traces of them. They recall the light from above the tower in the painting “Criminal,” which represents not the power of the moon but the power of the colonial state to name, track, and control. Or, in “Innocent” is it the heavenly light of relief that finally welcomes the boy upon his death?

This light also recalls “Guernica” (1937) in which Picasso’s disturbing lightbulb is one of interrogation, surveillance, or illumination of the darkness of utter destruction of a Basque town by Fascist Spain and Nazi Germany.

While the signifying signposts of “Guernica” and Young’s other paintings haunt “Innocence,” it is the boy’s facial expression that tugs at the heart. Such a realization goes at the Palestinian experience today. The Palestinian experience tells of an attempt to speak a heartening story under ever-devastating contexts. The lionized strength of the Palestinians speaks from the rubble of Israel’s destructive power, whether it is Gaza, or 1948 Palestine, or the West Bank, which is equally being further fragmented into separate archipelagos of meager existence. It is a slow and unacknowledged death from an ever-increasing stranglehold.

Does the boy staring at us demand that we do something to help? If so, what? And how? Does the viewer have the power to affect change after seeing the painting? Or is the viewer equally trapped? Is it only psychological torment the artwork produces? Or is the painting a call to action? Today’s U.S. and European campuses have managed to bring the issue of Palestine into focus, garnering ever more public support for the Palestinian cause. But the demonstrations have not slowed down or affected the speed of Israel’s genocide of the Palestinians.

It seems creating more freedom fighters against an onslaught of doublespeak has in some countries like Germany meant the equation of anti-Zionism with antisemitism. The metaphorical Palestinian face seems larger than life but so does a person on a missing poster. To whom does one seek assistance when Israel has destroyed all of Gaza’s infrastructure, or utterly controls all aspects of governance in most of 1948 Palestine? To whom does one seek aid when students, professors, and activists speak out only to be hounded by the modern police state that claims to be hemming in hate-speech while committing unspeakable atrocities in alliance with the Israeli colonial juggernaut.

Young’s artwork itself is a process of speaking to such an inability of finding answers, whether it is addressing generational divides that has opened up an abyss of catastrophic trauma, or attempting to find answers among the background of the rubble of Gaza. Still, the background’s horror seems to overcome the larger-than-life boy whose innocence of the painting prevails against the sheer power of technological barbarity.

If the boy floating from beneath the weight of Gaza’s ongoing Nakba can be read as a return to the taking of innocent life that nothing can recompense, Young’s painting “Trashed” (2012) goes to a site of the Nakba not mentioned enough in the media — the refugee camp. This camp here is not in Palestine but in Lebanon. Moreover, it is not just in any refugee camp but Sabra and Shatila, which bears its own history of devastation, as a site of suspended life since 1948, and the mass murder of Palestinian life in 1982 by Lebanese Phalangists who were supervised by the Israelis. Today, the camps stand as the disposable life that the state of Lebanon gives to its own neglected population in the present day.

“Trashed” is not just a mark of how the Nakba of 1948 has affected the Arab world. It symbolizes the desire of the imperial world to turn the region into a “Middle East,” a subservient proxy of imperial power that produced nations and divisions within and against Arab populations and others who coexisted with it.

“Trashed” also showcases how the 2015 garbage crisis in Lebanon, which ordinary citizens have complained about from time to time, has worsened around the refugee camps, sites of disposable life. Even the symbol of Palestine in the shape of a key has been demoted. It appears not as a key but an illustration on the cover of a book among the debris beyond the child’s reach. It is a sign of a once held dream, which like many of the other parts of the catastrophe, grows on the trash pile of its history.

The re-working of the similarly conceived “Trashed (Aftermath),” is a response to the Port of Beirut explosion of August 4, 2020 which devastated much of the city. In it, Young’s painting shows the child nearly indistinguishable from that garbage. It renders not only the physicality of life but the psychological life of a child ruined by wretched everyday existence.

Young’s art shows how a once touristic destination of beauty that Lebanon represented to a European audience can be overcome by human detritus in a weakened state. He also extends this ethos to the country’s most vulnerable and profound site — the refugee camp.

However, these places of wretched existence are hardly recognized. The realism of the global world is governed by build-up and cover up. Realism does not admit and face up to the problem that globalism brings. The title of Young’s “Catastrophe (Les Voyeurs)” (2015-24) is significant. It brings an event and a perspective together. The perspective of the on-looker/ viewer is a side that is commonly seen. That viewpoint is the one informed by a simulacra of mainstream news coverage. The ones who suffer are not deemed recognizable except in symbolic utterance, for instance, with a UN tent. Still, parentheses are crucial here; they not only suggest those and that which are being marginalized but who and what cannot speak publicly. In this case, the onlooker is marginalized, a rare occurrence.

In titling this painting in such a way, Tom Young tries to depict the catastrophe, not those who watch on or over it. The height of the cable-car suggests that the happy detached tourists’ life may be suspended. In this suspension, it is the life below, the reality of desperate suffering that takes on central attention. It is not Nietzsche’s tightrope walker’s concern with getting to the other side, or in this case, the people in the cable car, but the scene below which must be attended to in the painting. Cable cars are usually seen crossing over touristic sites, concerns of modern capitalism and urban design, that promote investment over people’s lives. Since Rafiq Hariri’s 1992 project to redesign Beirut after the Civil War, Beirut has seen a massive build-up of investment that covers over the past of the city and its ever-swelling refugee crisis. That build up has been labored over by a refugee population living under a substandard living wage which is never seen. Young’s canvas does not, however, paint this scene. In the present time and condition of his canvas, the U.N-supplied tents take center stage and not refugee life within them. More importantly, the state that gives agency to the U.N. to protect refugee life lies weak and in ruins, rendering U.N claims of protection for refugees meaningless.

The painting’s background leads not to protection but to destruction. Whether that destruction is of the former life in whatever state, who can tell? Whose people’s history the painting represents is not known. It is just rendering the life of so-called international protection absurd. Still, the painting presents refugee life in its most precarious and silenced form. The viewer looks out to the vanishing line of the sea and the horizon. It is not hope that one encounters but a late and uncanny Turneresque flame-like sunset of blues and oranges. This sunset is not a romantic scene; instead, the foreboding glow suggests the mytho-poetic license of a catastrophe that is rendered without its victims being identified. All that can be noted is the life that would have been there but that can never again speak for itself.

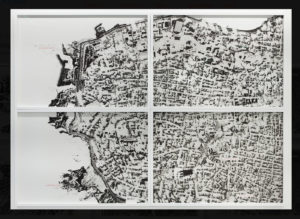

Throughout Young’s tenure in Lebanon, he has painted large landscapes of Beirut that would play with the romantic ways of depicting and viewing landscape art. His technique washes over it to deny its possibility; a romantic idyllic scene of swinging in the center of Beirut is denied as absurd. Now, he will tie this denial to a capitalist twinning of the empire that once was to the devastation of its investment. In “Double Standard” (2024), Young’s canvas works over the earlier denials of romanticism with an anti-capitalist and anti-imperial critique.

Hypocrisy is laid bare: in the lower-left corner of the painting lies the undeniable realization of London’s iconic Tower Bridge, and by its side the utter destruction and devastation of colonial rule. Unlike “Catastrophe (Les Voyeurs)” there is no doubt that this artwork is calling out one source that has brought on this wreckage: the Imperial might of Western capitalism bringing unimaginable suffering to the colonized Global South, and perhaps back on itself.

Again, it is seen from above, from the view of a detached witness. It aims a strike at the metropole of Young’s homeland Britain, synecdochally represented by its famed bridge, and its imperial ties to a destroyed Palestine, likewise its expression of Empire, through Charles Dickens’ 1863 Great Expectations. Wemmick, a central character of the novel and at particular times the greatest adviser to the protagonist Pip, tells him:

Choose your bridge, Mr. Pip…and take a walk upon your bridge, and pitch your money into the Thames over the centre arch of your bridge, and you know the end of it. Serve a friend with it, and you may know the end of it too, but it’s a less pleasant and profitable end.

In Dickens’ bleak novel, the prose strikes a seemingly wonderful act if done singly for one’s own interest. The interest in Dickens is never single because Pip is doing it with money earned by Magwitch who, as a prisoner of His Majesty’s government, succeeded and thrived in a penal colony. But Dickens’ novel is hardly post-colonial. Even Wemmick’s advice is to give Pip to himself alone and to ignore Herbert Pocket to whom Pip is trying to help.

Young’s painting asks: what of that investment? What does it mean today? The answer is a swept-over denial of that romantic investment, an investment that has produced refugee lives and devastation. It has not only answered back to the mytho-poetic feel of “Catastrophe (Les Voyeurs)” but it has answered a question Edward Said often asked when tackling Zionism: who are colonialism’s victims? The juxtaposition in Young’s painting is stark and meant to pose for those who look on to make that connection.

The purpose of art has often been claimed to be for enjoyment, not for questioning. This is not Tom Young’s ethic. On the surface, his art pays homage to more formal ways of seeing, yet simultaneously asks serious questions about the image, the structure colonialism has caused, and its lasting impact in the present of the region in which the painter inhabits. In his artwork from the last 18 years, it is clear that the devastation that the Arab world has and continues to endure is not dated to his lifetime or mine but to a much longer hold that needs to be acknowledged by looking at these works of art from a multi-dimensional critical perspective.

Postscript from Tom Young, 3rd of October 2024:

—Tom Young

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)

Thanks for this fascinating overview of Mr. Young’s artistry — his “ethically motivated art.” The juxtaposition of his contemporary work with that of Van Gogh, Picasso, Dickens is precious…! Kudos for the excellent presentation, Mr. Ziad Suidan!