The latest earthquake disaster in Turkey and Syria swallowed many thousands of people and terrifyingly reminded this writer of the previous disaster that occurred in her Istanbul childhood.

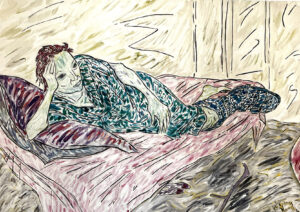

Sanem Su Avci

I woke up the morning of Monday, the 6th of February, 2023, to find worried calls from my father on voicemail and messages on our family chat about a powerful earthquake in the southeast of Turkey. Our nuclear and extended family all lived far away from the affected zone. Nor did we have roots or a house in the region. My parents couldn’t express why they felt so worried, but I understood. Once people woke up and heard the news, the phone network crashed because of overload. Everybody tried to reach their loved ones because we all knew that a morbid lottery had hit some of us. Entire households were lost after going to bed on a Sunday night, in a sudden but expected event. In the short phone conversations we had later in the day, my parents lamented not only the lost lives, but also the lost hopes. Massive death resulting from a foreseeable natural event was the fate that befell Turkey, despite all the public and private efforts to evade this fate.

The official death toll of the February 6th earthquakes in Turkey is lingering above 50,000, but witnesses estimate a much higher figure. It is reported that hundreds of thousands of mobile phones and credit cards were never used after the earthquake. Many of the dead have not been found, as they were fused with the rubble of what was once their home. Many were buried without official procedures. Many of the trapped perished slowly. Survivors heard their calls for help without being able to save them, as cement blocks could not be lifted with the bare hands of a few survivors. Rescue teams and equipment often didn’t arrive for many days.

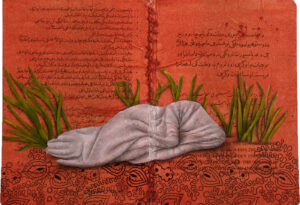

Terrifying images and information flew in from the region. People wrapped in blankets stood around collapsed buildings from which smoke was rising, while it was raining or snowing. Addresses of those affected circulated on social media — “nobody came to help,” people repeated. A video showed a woman crushed between two floors, her pale hand outside the rubble, bracelets and rings shining in the dark. Another video showed a teenager running around the heap of debris, crying that he would never be able to find his parents. One teenager had shot a video of himself trapped under the rubble while the shaking continued, reporting that the building continued to collapse and that he was being crushed. When I wasn’t looking at the screen, I looked at the walls of my apartment in Athens, where I live, imagining their collapse. If all the walls in a city collapsed within an instant, there would be no separation between inside and outside. That might explain why looters had reached the earthquake zone before rescue teams — for the deprived, collapsed walls meant opportunity.

Another Earthquake

One of my first memories is of an earthquake during which adults lift me and run. Earthquakes are scary, and they happen often in Turkey. The images of destruction from the relatively minor earthquakes in 1995 and 1998 had already been ingrained in my child’s brain when the deadly earthquake in 1999 in Izmit, near Istanbul, reconfigured the earthquake memory of the whole country.

After the 1999 earthquake, as a ten-year-old interested in public affairs, I spent a lot of time looking at disaster images. I dreamt of one day becoming a rescue worker — a hero like the volunteers of the Search and Rescue Association (AKUT) who had saved so many people from collapsed buildings. I had trouble sleeping at night, overwhelmed by the thought that our family shelter could devour us. I lost my faith in an interventionist god during one of those sleepless nights. Trying to pray myself to sleep, asking God to put off the big earthquake that experts on TV and newspapers were saying would hit Istanbul sooner or later, it suddenly dawned on me that tectonic plates would not change their movement because I was unable to sleep and had taken to praying compulsively.

Earthquakes never ceased to be part of the agenda after 1999, neither of our family nor of the country. Others, too, thought that it had to do with God. On the one hand, Islamists in opposition argued that the earthquake hitting secular holiday towns and destroying army barracks was divine punishment. On the other, their young and charismatic leader Erdoğan claimed that it was the incompetence of the government that turned a natural event into such a disaster. Indeed, the allegedly strong public authority in Turkey had seemed nonexistent after the 1999 earthquake. The army, NGOs, and political parties rushed to the zone to help, but the government itself could not intervene. The post-earthquake government response seemed to confirm the (neo)liberal claim that statesmen were by definition incapable of responding to crises. Erdoğan’s newly-founded party, which had its roots in political Islam, came to power claiming that it included the civilians who could bring justice and development to the country, and that since the Kemalist state had long excluded them over their Islamic politics, they had no stake in this incompetent regime.

During the years that followed, many things changed in Turkey, but most clearly, the cityscapes changed. The economic model of the Islamist government was centered on construction. Private companies close to the government became gigantic by building airports, double roads, bridges, and tunnels all over the country with public funds. The government used these works as evidence of the development they enabled. Highrise buildings popping up on agricultural land in many of the mid-sized towns across Turkey became a sign of prosperity. In many of the smaller cities, private industries competed in the global market through drastically underpaid labor. People complained of poverty and human rights violations, but injustices would be silenced by pointing at buildings.

Waiting for the Big One

In Istanbul, where I grew up during the Erdoğan era, popular low-story neighborhoods in the center were demolished and their low-income residents sent away, based on the post-1999 legal framework for earthquake preparedness. Skyscrapers or luxury residences were built in their stead. Every few months, a scrap of seashore or a little park would be cordoned off for development. The city extended in every direction except the south, which was bounded by the Marmara Sea. Underneath the Marmara was the faultline that would create the Big Istanbul Earthquake. Some of the poorer neighborhoods with large earthquake risk were not reconstructed because their reconstruction did not promise profits. Istanbul became a gigantic city with high-rise buildings, with wide highways that connected them, and with close to zero green areas, in a process of “urban transformation” that was legitimized through legal frameworks based on the need for earthquake preparedness.

My parents had both studied engineering at the prestigious Middle East Technical University. By the time they graduated, the coup of 1980 had just crushed the vibrant socialist movement of the 1970s. Their chances for serving the people were minuscule. Their education and salaries in the private sector, however, allowed us to choose houses in Istanbul based on the quality of construction and ground condition. As I grew up and went to other houses, first to stay overnight with my friends and then to live, I would have my eyes on the corners of the ceiling and the occasional crack in a column. My mother worked on projects for the preparation of public schools for the expected Istanbul earthquake, and as a teenager I had learned from her how to assess, roughly, the earthquake resilience of a building with my eyes.

In November 2022, in its 20th year, the Islamist government staged an earthquake drill in which it advertised the method of cowering next to solid furniture for protection. Supposedly, buildings would stand, but furniture could collapse during an earthquake, so it was best to cover up and wait for the shaking to end. Around the same time, the owner of the little grocery store where my parents bought their olives was asking my mother what to do when the big earthquake hit. His shop was on the ground floor of a five-story building by the Marmara shore. Cracks between the floors were visible in the façade of the building. My mother advised him to run out the moment he felt shaking, since the building was likely to collapse in a strong earthquake. Given the situation of the real estate market, with the inflation and the rising rents, it was out of the question to move his shop to another, safer place.

An Expected Disaster

Geologists appeared regularly on Turkish TV after 1999. They often mentioned risk in the area of Maraş, where the earthquake storm took place on February 6th, 2023. The Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD), a newly-built directorate within the Ministry of Interior Affairs, had chosen the province of Maraş as a pilot zone for risk reduction in 2020. Since the scale of destruction does not make sense to those who are not familiar with the Turkish context, many foreign observers jumped to the conclusion that, to have suffered such widespread damage, this region must have been a neglected region with a forsaken minority population. But the city of Maraş was an Islamo-nationalist industrial hub which had been ethnically cleansed a few times during the 20th century — emptied of Armenians in 1915 and in 1920, and of Alevis in 1978. Many of the worst-hit cities heavily voted for the government and even those who didn’t, like Antakya, still received government investment and attention. The new airport of Antakya was built during the 2000s on a dry lake, right on top of the active faultline that would create the 2023 earthquake. Experts had objected to the choice of location, saying it was prone to flooding and earthquake damage. Their objections were dismissed with toxic demagoguery. The airport that started functioning in 2007 indeed flooded often and its runway was torn apart in the February quake.

The temblor, predicted by seismologists, damaged constructions of all types. Residential buildings, old ones where the poor lived as well as the newer ones which hosted the rich, collapsed. Newly built airports, roads, and bridges were damaged across a wide area. Hospitals either collapsed on top of staff and inpatients or became unusable. Government buildings collapsed, including the centers of the aforementioned AFAD. Why and how had they built like this, knowing that strong earthquakes would happen? After the earth swallowed whole neighborhoods and towns, Erdoğan argued that almost all of the collapsed buildings had been built before his term, but in fact numerous lives were lost in the monstrous rubble of newly-built luxury residences.

In the 1999 earthquake, the contractor model had been held responsible for the destruction. In this model, a contractor, who was not expected to have any specific education, would build and sell houses whose construction process would be controlled by public or semi-public bodies. This model was not altered during the Islamist era, but brought to an extreme. The government designated pieces of land for development by favored contractors while the task of construction control was privatized. The Union of Engineers and Architects was stripped of its right to oversee construction control a few months after the demonstrations in 2013, in reprisal for its stark opposition to government plans for constructing a mall over Gezi Park in Istanbul. Amnesties would be introduced every few years to register irregular constructions, further eroding the function of construction control. Still, why did the government permit the construction of buildings that would collapse in the expected earthquake? Maybe the answer to that question is the same as the answer to the question of why the government kept following macroeconomic policies that since 2018 have reduced millions to penury: an answer that we cannot fathom.

The Current Situation

Authorities had been slow to respond to the 1999 earthquake, but the head of government at the time, Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit, had appeared hours later in the earthquake zone, apologetic and alarmed. Following the 2023 earthquake, the first on-camera appearance of the government came from the Minister of Environment and Urbanization, who said that the government would not allow any coordination of rescue efforts other than by AFAD. Volunteers and expert rescue teams were kept waiting during the first and most critical hours of the earthquake because the bureaucrats of AFAD could not or did not permit them to operate. There are countless painful accounts of their deadly incompetence, their cutting the organic bond between people who were in need and the people trying to help them, in an effort to prevent the emergence of non-governmental heroes. Unlike in 1999, the army was not mobilized for rescue efforts since, as the army chief of staff would say days later, it had to protect the borders and its positions in Iraq and Syria. The star NGO of the previous earthquake, AKUT, had been seized and rendered ineffective through government intrigues in the previous years. New NGOs were coming to the fore in response to the many disasters that befell the society of Turkey, such as the help network, Ahbap, run by former rock star Haluk Levent, and received funds from the many people who wished to send financial aid to a body that was not linked to the government. Government pundits were calling for all donations to be made to AFAD or to the Red Crescent, since these were the designated public organizations for disaster relief.

Erdoğan seemed completely detached from the emotional reality of the people during his first post-disaster public appearance on the second day of the earthquake, when, speaking from an indeterminate studio, he threatened his critics by saying that they were keeping notes of all those “spreading disinformation,” and would open that notebook when the time comes. Twitter was banned a few days after the earthquake, while people were still calling for help on the platform. On more than a few occasions, it was revealed that aid material that was urgently needed in the earthquake zone traveled around the country or was stocked in some depot. An app for reporting disinformation about the earthquake was launched hours after the quake and a few days later people were already being detained for disinformation, sometimes because of the tone of social media posts in which they called for help. People waiting around collapsed buildings for the bodies of their loved ones or opposition leaders mobilizing to rebuild the torn runway of an airport, all felt the need to say somewhere in their speech “let them put me in prison if they want,” knowing that they would be facing this threat.

Meanwhile, in the prisons, prisoners who wanted to go out and help their loved ones were killed at least on one occasion. In the big earthquake that had happened in Erzincan in 1939 — the only disaster in the history of modern Turkey that can be compared to the one in 2023 in terms of magnitude and the dilatory nature of the response — prisoners were temporarily freed to help in the rescue efforts. This was during the times of the Kemalist regime, which the Islamists never ceased to accuse of being estranged from the people.

The Dream

On the second night of the earthquake in 2023, I had a dream in which I saw myself as a rescue worker in an earthquake zone. My sister was a preschooler, as she had been in 1999, and her kindergarten was on the floor of a building that had collapsed in the earthquake. She and her friends were trapped under the rubble. I went into the rubble to take them out. I was surprised by my superpowers — I could pass through concrete. But I could not find them anywhere. I woke up with the sorrow of losing my sister, which took my breath away. When I recollected that my sister was an adult and was not trapped under the rubble, I took a deep sigh which was followed by piercing pain, because this nightmare was the reality of so many people at that very moment. The earthquake in 2023 had taken me back to 1999, when I was a little girl who pictured herself as Lara Croft from the Tomb Raider, and cared for her sister more than anything else. When I called my sister to tell her about this dream, she told me of a revelation she had just had, after a long day spent crying in another corner of the world. When she heard Erdoğan threatening his critics in his first public appearance after the earthquake, she remembered the moment when, as a child, she first decided to leave the country; it was upon listening to a speech of his on the radio during the early years of his government.

The daughters of a well educated couple of white-collar workers, we had both become emigrants in search of better prospects and some peace of mind. In our country of origin were immigrants and refugees from other places, many of whom resided in the earthquake zone. A Syrian father had been beaten up in front of his collapsed house, waiting for his two sons to be taken out, by people who thought that he was a looter. Other refugees had not called out for help because they were frightened of being recognized through their accent and being attacked. The frustrated population was fed with rampant anti-refugee sentiment, diverting their anger towards easier targets, even though they shared the same fate.

My first days after the earthquake were marked by shock and anger. Sadness kicked in later. Then, when the weather was nice and sunny, when there was no longer hope of anyone being pulled alive from the rubble, and the government had done a televised ceremony in which the rich pompously donated very little and very late, I felt rage. I was observing my changing emotions with wonder when they were muted yet again by the news that the Red Crescent had been selling tents and other emergency supplies after the earthquake, instead of donating them. The information was unwittingly revealed by the head of the philanthropic organization Ahbap, which had risen to prominence after the earthquake. Just a few days before this documentation, Erdoğan had used the heaviest words ever uttered by a Turkish president for his critics, naming “honorless scums” those who accused the Red Crescent for not responding appropriately to the disaster.

The main humanitarian organization of the country not sending tents to earthquake victims left homeless in freezing temperatures unless it received money was a new low. The day that the Red Crescent scandal became known to the public, my mother’s voice on the phone sounded as painful as in the first days after the earthquake. My father could not find the words. They, more than me, were trying to navigate a sense of futility. They were the successors of a generation of technical students who had opposed the construction of the bridge over the Bosphorus during the 1960s. The quiet waters of Bosphorus could be easily crossed with boats, the students said, while in a secluded corner of the country, in Hakkari, people were drowning regularly while trying to cross the exuberant Zap stream. If a bridge were to be built it should be built over the Zap, they said, because public works should prioritize public benefit over profits. So they went and constructed a suspension bridge over the Zap stream with their own resources in 1969 and named it after themselves.

The Revolutionary Youth Bridge over the Zap stream served the people for free until it was destroyed by unknown assailants in 1999. Revolutionary youth themselves were destroyed physically and symbolically throughout the late 1970s and the 1980s, creating a political vacuum that led to the rise of Islamist politics in Turkey. In 2018, as an economic crisis that would in a few years push half of the population’s income below the hunger threshold was just starting, a group had stenciled the walls of Istanbul with the slogan: “Turkey our home, Erdoğan our father.”

Where do we go now that our home is devouring us?