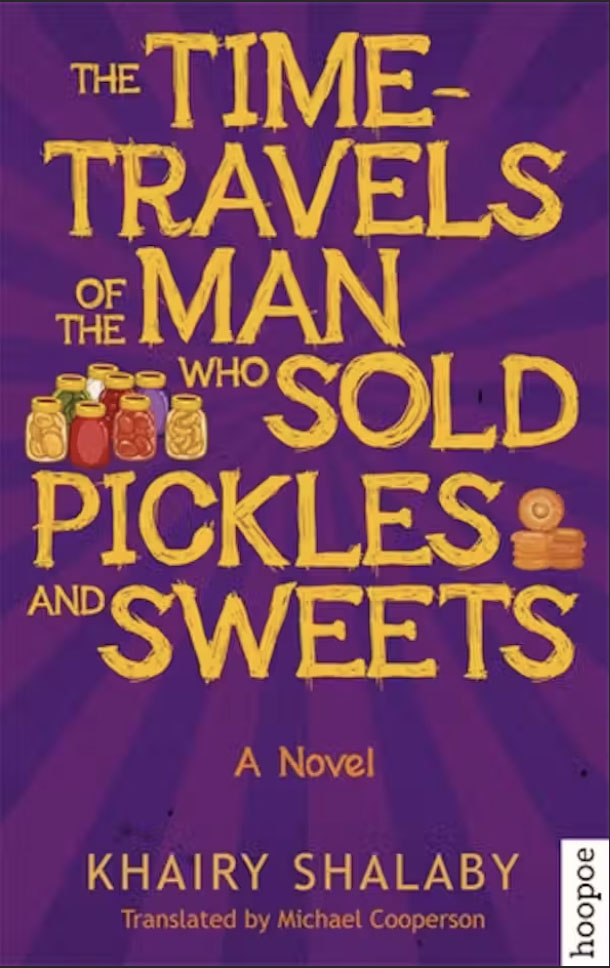

Temporal displacement: the author’s alter ego wanders through ancient streets and gates of the Mamluk era, meets Egypt’s greatest historian al-Maqrizi, and has a run in with a grumpy Andalous scholar and mystic, Ibn Arabi.

“What year is this?” “792”

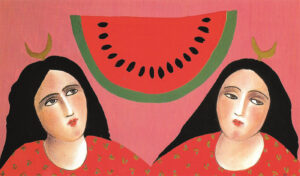

I had ended up in the wrong time. I walked away, wondering how to get back to where I had come from. But the crowd pulled me along, this time to a festive tent full of watermelons and a throng as big as any in late-twentieth-century Egypt. Sitting nearby was Maqrizi. I thought he might be waiting for a watermelon to take home to his family, but he turned out to be questioning a boy who looked like a vagrant. I asked what he wanted from him.

“He and one of his friends work in the stables,” said Maqrizi. “On this blessed Ramadan night, they stole some twenty watermelons and approximately 30 wedges of cheese.”

“Do the melons and cheese belong to you?”

“No, I’m only asking him how he did the deed, so I can write it down.”

“You,” I said, “are a truly great man.”

He looked at me suspiciously. “Didn’t I see you being arrested by Gohar’s troops?”

I admitted it.

“So what do you want, exactly?”

“I have an invitation to break the fast with Mu‘izz, the Fatimid caliph.”

“On the occasion of what?”

“The first Ramadan to be celebrated in Cairo.”

“Go back the way you came,” he said. “At the moment, you’re walking along a line between the two palaces. The Fatimid caliphate has fallen to the Ayyubids, and the square’s been thrown open to the public, as you can see.”

He must have realized that I was a person of some importance, especially after I balanced my Samsonite briefcase on my knee and opened it with an impressive click. I brandished the gold-engraved invitation card from Mu‘izz, thinking that even if the visit didn’t work and I found myself busted flat I could sell the gilt to a goldsmith. That’s why I kept it at arm’s length and why my hand trembled when Maqrizi reached for it, hoping to read it: the card itself was so splendid that I should be able to pawn it for cash if I had to.

Maqrizi smiled. “Where were you before you came here?” “I was coming from the Mosque of Husayn, going through the gate on the other side past the souvenir shops toward

Mu‘izz Street. The next thing I knew, I was here.” “Good enough,” he said. “See that big gate?” “Yes.”

“That’s the Daylam Gate. It overlooks the courtyard called Bashtak Palace Square. If you walk through the courtyard, away from the Storehouse of Banners, you’ll end up at Husayn. It’s actually right behind you, but there are a good many years in between. From the Daylam Gate you can go through to the Saffron Cemetery Gate, which is the burial ground for the caliphs and their families. By the way, the Saffron Cemetery is going to be the site of the Caravanserai of al-Khalili. Have you heard of it?”

“I’ve never seen the caravanserai, but in my time Khan al-Khalili is world-famous.”

He nodded and then said as if it were only a day between, “All that’s left is the name. One more for Egypt to remember!” He continued, “Anyway, between the Daylam Gate and the Saffron Cemetery Gate are the seven passages the Caliph uses on the bonfire nights to reach the observation tower on al-Azhar Mosque, where he and his family sit and watch the fires and the crowds. You can go through Saffron Cemetery Gate to Reeky Gate.”

“Where’s that?” I exclaimed.

He pointed to a grand old gate and said, “That’s it.” “The gateway’s still there in my time, too! I’ll stand in front of it and hold on—maybe it’ll pull me from the bottom of time up to the surface. From there I can come back down the well the right way.”

Smiling, Maqrizi asked if I was invited to break the fast. When I said I was, he asked me if I knew what “Reeky Gate” meant. I said I didn’t.

“It means ‘Kitchen Gate,’” he said. I looked toward it longingly. Maqrizi tugged at me gently and sat me down at his side. Then he pulled out a pocket knife—not a switchblade, which would have been illegal—with a handle elegantly decorated with Quranic verses and radiant Islamic designs. He rolled one of the watermelons over, tapped on it like an expert, stuck the knife into it and cut twice, then drew out an enormous slice and offered it to me with the suggestion that it would cool me down. I buried my whole face in it, indifferent to the mess it would make of my suit, tie, and shirt collar. As he sedately carved out a piece for himself, Maqrizi asked, “Don’t they have watermelon in your time?”

“No, by God,” I said, “only something like it, that goes by the same name.”

“May God rest the soul of Ibn Arabi, who wrote: ‘When Jupiter enters Gemini, food becomes dear in Egypt. The rich become few and the poor many, and death takes from them its tithe.’”

“So when does Jupiter enter Gemini?” I asked.

“Every 30 solar years,” he said. “It stays there about 30 months.”

“Ibn Arabi was right about some things,” I said, “but the more poor people there are, the more rich people too—and the higher their property values.”

“In that case,” said Maqrizi, “Cairo’s sign of Aries must still be ascendant.”

“It’s almost time,” I said, “for me to meet Mu‘izz!”

“I happen to know that Mu‘izz arrived here at his palace on the seventh of Ramadan, ah 362.”

“Now I can get there with no trouble,” I said, writing the date in my appointment book. “I’ll just take the direct bus.”

I bid him farewell. Embarrassed at the condition of my suit, I tried cleaning it off with a handkerchief, but discovered that all the dust in Cairo had come off my face onto the cloth. Laying it on my wrist, I folded it over to get the clean side up; but every time I did, I would start sweating again and have to wipe my face, which dirtied the handkerchief all over again. The prospect of facing Mu‘izz’s guards in that condition was a depressing one. I might even be arrested and interrogated by the police, with unpleasant consequences. Leaning against the Reeky Gate, I ran a hand over it. It stood firm and strong: not a relic yet. People were staring at me, some suspicious, others amused.

“He must be a Crusader,” said a young donkey-driver. “Fool!” said a tripe-seller pushing his cart. “He’s a Turk.” A peddler girl joined in: “No, he’s a Daylami!”

Poking at her with his staff, an old man launched into a rant: “Turks, Daylamis, Zuwayla, Franks, Persians: there’s no way to know where anyone’s from anymore!”

The peddler girl stopped in the middle of the crowd and turned to face the old man — and me, too. She was beautiful: a product of Turkish, French, Greek, Persian, Caucasian, or Ethiopian blood, or most likely of all of them together, and a descendant of one of the former palace slave women and an emir, perhaps. Looking me over, she pronounced with formidable authority, “Poor thing! He must have been captured by slave traders centuries ago and wandered off on his own. Are you still lost, sweetie? Don’t worry, someone here will give you a place to sleep and bread to eat. What a city: cruel and tender all at once! This jinx of an old man thinks I’m an ignorant girl or a common whore, but he should know that I’m a lady of the day, not only of the night; and I can read and write, too. All those kings and emperors started out as slaves, but they fought and plot and schemed until they came to power—and turned into bloodsuckers!”

The old man curled his lower lip in distaste, brandished his stick, and said, “Get away from me, you she-devil! Go back to your house in Dar el-Ratli, or wherever the hell you live.”

With a sprightly bow, she said, “All of Cairo is my home. You spend the night in any one of the 100 open mosques, but I spend the night in the hundreds of eyes enchanted by my beauty and the hundreds of hearts move by my plight. My plight is theirs and theirs it mine; and how pretty a plight I have!”

She turned, making the light sparkle on her costly frock, and disappeared into the crowd. The old man shook me, saying, “My name … My name is …” When he saw that I was paying no attention to him, he shook the stick in my face and walked away, muttering to himself. When he vanished, he seemed to have given the whole scene permission to vanish as well. For an instant, I could see nothing, though my head was filled with the echoes of sweet voices softly chanting songs of Spain.