A flight from war and a never-forgotten day at the beach.

Armed with his new and shiny new iPod, Malek entered the bus with heightened confidence. He clipped it to his waist and walked to the final row, looking cool and nonchalant. He sat next to Najeeb who was eating a labneh sandwich and drinking a Balqees orange juice. “I see Mimi’s back from the US with a new toy,” Najeeb said with a smirk. Mimi was Malek’s sister, studying architecture in Rhode Island and every summer she brought back the latest gadget to her little brother. “You bet she is,” Malek said. “I already took it to NabilNet and he uploaded all of Britney’s songs on it.” Najeeb pulled Malek from the back of his neck and said, “Play oops I did it again right now!”

As the song played, Spears’ effervescent voice put Malek and Najeeb in a hypnotic state, until Najeeb with his nasally speech found himself singing with expanding passion: OOPS I DID IT AGAIN WITH YOUR HEART. Their friends on the bus burst into abundant laughter and they awoke Eman who walked to the end of the bus and said, “Najeeb! Malek! Stop with this nonsense. You should be listening to Fairuz and Wadih El Safi, not some dumb blonde from the US.” Najeeb, offended by her comment, took the headset off and said, “Madame, who is Fairuz?” A look of shock crawled across Eman’s face and she said, “Your parents did not raise you well.” She walked away as Najeeb giggled and Malek whispered, “four-eyed witch.” Eman’s glasses were red, circular, and larger than life. She often took them off and told the kids on the bus the same story: “After the war I was part of a widowed women’s commune crocheting traditional Lebanese patterns and selling them to clients in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. It was good money, but it damaged my hands and eyes. Look how my right hand trembles.” Eman used the money she saved up from crocheting and opened a summer camp that would take children and teenagers to different cities, towns, and villages across Lebanon. “Mimosa,” she called it, after her favorite summer drink.

Najeeb and Malek were on their way to Edde Sands, the newest beach resort in Byblos, and the place to be seen during the summer of 2006. The mood on the bus was somber, Rayya, the chaperone who had just failed her Lebanese Baccalaureate exams was talking to Eman about a potential war with Israel after hearing of border tension in the south. “No one has time for war,” Eman assured her, “It’s too hot.” They arrived at Edde Sands at 10:00 a.m., Eman wore her sombrero, looked at Rayya and said, “Forget about the exams. You’ll have your remedial ones in August. Go out and enjoy our God-given sun.” Rayya and Eman rounded up the kids, those under the age of 12 went with Eman and those over-12 went with Rayya to the adult pool. They entered the resort as a shirtless man wearing purple shorts gave each of them a bracelet that had “live love Byblos” written on it. They walked across a botanical garden with koi ponds on each side and the shirtless man who introduced himself as Charbel said, “We imported these beautiful and colorful fish from Japan. No other place in Lebanon has this.” He walked them towards the pool, which was large, rectangular, and engulfed with hundreds of purple chaise longues. “As for the pool, it’s designed with a Phoenician sensibility — elevated, and facing the sea to remind us of our ancestors and their journeys,” he said with a wilful smile. Rayya, unimpressed, looked at Charbel and asked, “Where is the lunch area?” Charbel smiled and said, “Great question! Bacchus restaurant is up north from the pool and here are your lunch vouchers.” “Merci,” said Rayya while Charbel nodded and walked away. She then looked at the kids, hardening her voice and said, “Laiko ya shyateen. You know my rules. I don’t want to see it and I don’t want to hear it. And most importantly I don’t want Eman to hear it. Do whatever you want, don’t drown, and be back here fully clothed and sleepy by 5:00 p.m.” Rayya unpacked her bag on the chair next to her, took out her cigarettes and told Najeeb and Malek to get her a cranberry Bacardi breezer.

Malek and Najeeb found a couple’s sunbed at the top corner of the pool with purple towels and under the shade of a fig tree — not sitting with crowds was a practice that held their friendship of over five years together. Next to the bed was a decorative green and gold statue of a Phoenician man with a pointy hat, rusting in the sun. Najeeb took his shirt off, hung his clothes over the statue’s head and jumped on the bed. Malek, afraid of the sun, kept his shirt on and took out a book from his backpack. “I can’t believe you brought a book to the beach,” Najeeb said. “Well unlike you, I like reading more than Barbar’s food delivery menu,” Malek said. “Fine! Give me the iPod then,” Najeeb replied. Najeeb played Cassie’s “Me and You” while Malek read from Anna Karenina, writing the names of the characters in an index with little notes so he didn’t forget who they are. “These Russians have so many names,” he said out loud to himself. The beach and its waves passed between their legs, but they lay still in their own world until Rayya awoke from her morning stupor, walked up to them and said, “Would one of you put some tanning lotion on my back?” Malek nodded in agreement and she gave him a bottle of Carrot Sun lotion. Malek lathered Rayya while Najeeb asked them to put some on his head, which his mother always shaved. Najeeb had rosy lips and eyes so green they sometimes seemed gray. Malek had hazel eyes and did not resemble Najeeb, but they both shared pubescent love handles, fed by orders from the Burger King under Malek’s house in Rouche. Rayya walked back to her sunbed while Najeeb and Malek walked to Bacchus for lunch. They handed their vouchers to the receptionist who with a jaded voice said, “Badkon burger or tabbouleh or tawook?” “I’ll have a burger,” Malek said. “Tabbouleh for me,” Najeeb replied as Malek looked at him with a look of surprise. “What? I told you I’m on a diet,” he said.

They sat at a table with a sea view, under ceiling fans that wafted the smell of the sea breeze and refined oil from the French fries. They watched the swimmers defy Byblos’ large waves, jumping in and out of them, vanishing into the water and reappearing. A woman standing with her back to the waves was struck with a monstrous one that unclipped the top part of her bikini. She covered herself, frantically looking for it as her friends hysterically laughed and yelled, “Mariebelle!” Malek and Najeeb also laughed. “Do you think they would let us order Bacardi breezers?” Malek said. “Habibi you’re 14 and people still ask you if you’re ten years old. Maybe grow a mustache first,” Najeeb said. “Maybe I should draw one,” Malek said. “You know, my brother told me if you don’t drink water at the beach the dehydration will make you feel drunk,” Najeeb said. And at that moment they both decided not to have water for the rest of the day.

When their lunch arrived, Malek commented that the burger tasted like kofta while Najeeb looked at it with envy, saying the tabbouleh was too sour. A short while later Malek heard his name being yelled with a frantic voice in the distance. “Malek waynak! Malouk, Malek,” a woman yelled. “What does Rayya want now,” Malek said only to look back and realize it was his sister Mimi. Mimi wore an oversized blue polo shirt on top of tight white shorts and sandals with silver cuffs. “I wish I was that thin,” Najeeb said while gawking at her. “Mimi, yiy, why are you here?” Malek said. “I called you a million times, why didn’t you answer your phone? War is breaking out and you two are having tabbouleh. What kind of of reckless summer camp is this?” Mimi exclaimed. “My phone is in my bag, what do you mean war is breaking out?” Malek said as he felt a dry lump forming in his throat. “On the news the Israelis are bombing everywhere in the south, left and right. They are saying the airport is next. Effat, who works at the duty free, called to tell us they began an evacuation plan,” Mimi said. “So what should we do?” Malek said. “Well, I don’t think they will bomb this beach?” Najeeb said. Najeeb had a calm fixation that never changed in matters of war and peace. “I called your mom Najeeb and she said she sent a driver to bring you back to Beirut. Malek put a shirt on, I packed you a bag. Mom is already on the way to Syria to buy us tickets to Qatar and be with dad. We have to go before the border closes,” Mimi said. She spoke so fast Malek’s ears did not have time to process it. “I’m not going to Syria! Are you crazy? We waited for this beach day for months,” Malek said. “Mimi you are exaggerating. It will calm down. That’s what Eman said on the bus,” Najeeb exclaimed. “Eman is delusional and I already told her I’m taking Malek,” Mimi said. “Malek, go shower. It’s going to be a long journey; half of Beirut is on the way to the Syrian border. We don’t want the car to stink of salt.” Malek, reeling from disbelief, looked at Najeeb and said, “Come with us to Qatar. They have a Zara there! And really big malls.” Najeeb laughed and said, “I can’t go habibi. Anyways you will be back here in a few weeks. Don’t worry. Now go before Mimi murders us.” They hugged, Malek walking away with Mimi and Najeeb turning to the beach.

When Mimi and Malek got in the car, he found his grandma, Anbara, in the front seat wearing a white kaftan with red roses and Abu Arab the neighborhood taxi driver. Abu Arab had bloated arms and biceps and a belly so large he drove with it. He often cleaned his teeth with a miswak after smoking Marlboro Gold cigarettes. “Oh god, not this man,” Malek said while Mimi pinched him and said, “Khalas, just ignore him.” During the Civil War, Abu Arab was an accountant for Al-Mourabitoun, a Nasserist paramilitary faction, who fought alongside the Palestinians. Known for exaggeration, he would often say, “When I would leave the house, the traitors would tremble and say, ‘Close your windows Abu Arab is here.’” Malek’s grandma, friends with Abu Arab for decades, would laugh and say, “You only left your house to buy kaak and flour! Which you would sell to us at a higher price. That’s how you bought all those houses in Bhamdoun. With flour money.” Abu Arab would grimace and say: “Allah Ysamhek Hajjeh.”

“Listen, Hajjeh, I will avoid the Arida Border Crossing. I am hearing from friends that the Israelis plan to bomb the coastal border between Lebanon and Syria. I will take you through the Klayaat Road to the Masnaa Border Crossing. It’s safer.” Abu Arab said. Mimi and Malek looked at each other knowing that Abu Arab always had wrong information. But their grandma nodded and said, “Tawakal and go. There is a nice woman there called Em Jorge who can sell us some manakeesh and lahm bi ajeen for the road. I will call her.” Abu Arab rubbed his hands with Bien Entre perfume and said, “Yalla bismillah, let’s drive.” As they attempted to escape the highway towards the Klayaat road, they drove by cars with different license plates and jammed vans with travel bags and sordid faces. Mimi and Malek played a game of spotting a car with a foreign license plate. “Nigeria,” Malek said. “Oman, Saudi — oh and there in the distance — an EU one,” Mimi said. Their grandma told them to be quiet and asked Malek if the beach was nice.

“It was really nice, the best beach resort I have seen in Lebanon,” Malek said.

“Teta, there is war breaking out and you are asking him how the beach was?” Mimi said.

“Habibti, I lived through three wars. If you are going to be afraid during each one, you will never have time to breathe,” said Anbara. “Isn’t that right, Abu Arab?” she asked.

“Eh Hajjeh! It’s the Israelis who are afraid of us. We don’t care, it’s just another day,” he replied.

Abu Arab began chanting revolutionary anthems from the Murabitoun while Anbara clapped and cheered him. Malek ignored them and stared at the sun setting outside a valley, it was so big he wondered if he could live in it. They drove across empty plains as the summer air tired their eyes, causing Malek and Mimi to fall asleep. Anbara dozed in and out of consciousness and occasionally asked if they arrived.

Abu Arab drove in silence for an hour, but as the night fell and the atmosphere was bereft of color, a trepidation creeped over him. He opened the radio to a low volume and heard the anchor say: Suspected attack on Klayaat airport. Sight of smoke. “Hamdella we crossed it safely,” he murmured to himself. He switched the channel to Sawt Beirut who was hosting the Minister of Tourism, who with a hysterical voice, discussed the potential financial losses of this war saying that they had a “record two million tourists this summer.” He was then joined by the President of Lebanon’s restaurant syndicate who demanded that the Lebanese government prevent the war from escalating. “This was supposed to be our summer of recovery,” he exclaimed. Anbara suddenly woke up, joining the disenchantment of the minister and said, “They never want us to be happy. Every time they see Lebanon prospering, they want to destroy it.” Anbara never indicated who the “they” were but her sentiment often carried enormous blame and accusation. Malek, bothered by their sounds, looked for his iPod to play some music, only to realize that he forgot it with Najeeb. “Oh no, my iPod, I forgot it. Turn back, turn back,” he began yelling. Mimi woke up and said, “Shu fee?” thinking something serious had happened. “Your brother is complaining about something he forgot. I told you to stop buying him these gadgets,” Anbara said. Mimi hugged Malek and said, “It’s fine, we will buy a new one in Qatar.” Abu Arab looked at them in the mirror and said, “Men these days, all they want to do is wear short shorts and put earphones in their ears. Malek, when I was your age my father gave me a rifle!” Anbara laughed and said, “He should have given you a mouthguard.” Abu Arab laughed and said, “Allah ysahmek hajjeh. Yalla, all of you prepare your passports. Hajjeh do you have the gift for the customs official?” Anbara nodded and said, “There is a box of Pepsi and 7 Up in the trunk and a hundred dollars in my bag. That should be enough.” Anbara then looked outside the window, took a long sigh, and said, “Oh god, forgive me, Rafik Hariri’s blood is still fresh and we are crossing through the country of those who killed him.” “It’s okay Hajjeh, god is too busy to care about Bashar Al-Assad and Hariri right now,” Abu Arab said.

They arrived in Damascus around 9:30 p.m. Anbara had asked Abu Arab to take them to the storied Abu Kamal restaurant on May 29th Street. Her son-in-law’s sister owned the restaurant and while Anbara did not get along with the Syrians, she loved their kibbeh. “I’m glad we made it in one piece with your reckless driving, Abu Arab,” Anbara said as she exited the car. “Hajjeh, the mountain roads into Damascus are full of wolves, I had to speed,” Abu Arab replied. “Khalas, khalas, stop talking. Yalla, let’s eat. Malek, Mimi, get out of the car. Your mom is waiting at the restaurant,” Anbara commanded. In the square near her, a bald man, noticing her Lebanese accent, looked at her and said, “Last year you kicked us out and now you need us for safety!” “Skot, I won’t be spending more than four hours here,” she said as she walked into Abu Kamal. As they entered the restaurant, Arabic music played from the underground where Abu Kamal’s nighttime haunt, Ali Baba, entertained musicians, Baath officials, and artists. Anbara told the kids she will go there and sent them with Abu Arab upstairs to their mother. They arrived on the second floor with empty tables covered in ornate white sheets and guarded by men in black suits and red roses pinned to their suit pockets. Their mother, Nadine, was sitting under a portrait of Hafez Al-Assad in a black suit and Bashar Al-Assad in military gear and Wayfarer sunglasses. She had two plates of cordon bleu, Abu Kamal’s signature dish, ready for them. She hugged them and cried, saying “I’m so glad you made it out safely.” Mimi laughed and said, “Don’t make a scene mom.” Nadine wiped her tears, looked at her and said, “I can’t believe what you are wearing! And in Syria! Go change now before we become the talk of the town.” Malek, famished, sat next to his mother and began to eat. She played with his hair and asked him: how was the beach?

At 2:00 a.m., Abu Arab drove the Mrayseh family to the airport. Everyone was too tired to talk, but Abu Arab, bothered by silence, opened the windows and said, “The Syrians are so lucky with their dry air. They don’t suffer the humidity of summer in Beirut.” Nadine lit up a cigarette and asked, “Abu Arab what will you do, are you going to go back to Lebanon?”

“Of course, I will, if I am going to die, I will die in Ras Beirut!” Abu Rab replied. Anbara laughed and said, “Nadine, how much do you want to bet he is going to take his usual hotel in Ladkieh by the beach?” Abu Arab beat the steering wheel of his car and said, “Allah ysahmek hajjeh.”

At the airport, people scrambled to buy tickets to all sorts of destinations. Nadine, proud that she is always ready, even in times of war, showed her tickets to the military officer. “Bel Salameh,” he said. They bid farewell to Abu Arab who smiled a half smile and when they finally boarded the plane, Malek looked at his mom and said, “Mom, can I buy a new iPod in Qatar?”

“We will see when we get there,” she said. For a month after, the war continued to rage, claiming countless lives and ravaging Lebanon. Malek felt lost and sad, spending most of his time shuffling between Al Jazeera and YouTube on his computer. He would speak to Najeeb on MSN Chat asking him how Lebanon was. “It’s the same. MISERABLE. But at least I have your iPod. On days when the situation is not too tense, my mom lets me go for a walk on the Corniche and I play music on it pretending it’s that day at the beach,” Najeeb typed. “I wish we never left. This is all just a nightmare, and I keep hearing my parents saying we might live here because they’re worried about sectarian tension in Lebanon. I can’t live here Najeeb!” Malek wrote. “Don’t worry, like I said, you will be back here in August. Plus, your mom will never survive in Qatar, it’s too beige for her!” Najeeb typed back. Malek laughed his first sincere laugh since leaving Lebanon and typed, “You’re right. Beige is not her color.”

One day, Nadine, who had made the living room her abode since the beginning of the war, emitted a loud cry and said, “It’s finally over. Guys, it’s finally over.” The Mrayseh family huddled over the tv and watched women throw flowers and rice across the roads in Lebanon as if it was a wedding. Anbara, standing in the middle, took on a somber tone and said, “Let’s pray for the lives lost in our country.” Malek looked at his mom and dad, happy that the war was over, but filled with dread that they would never return to Lebanon. And his eyes spoke of truth; the Mrayseh family never returned to Beirut. Malek’s father, Zahi, insisted that the family relocate to Qatar for their own safety and they enrolled Malek in high school there. Mimi eventually graduated and settled in the US, working at an architecture firm in Colorado while Anbara split her time between Qatar and Lebanon. Malek tried to stay in touch with Najeeb who immigrated to France with his mother, but somehow, their friendship, which survived so many crowds, could not survive distance.

One summer evening, Malek was visiting Beirut and he walked over to Bardo on Clemenceau Street to have a drink with his friend Rabea, the resident DJ on Fridays. Malek sat next to Rabea as dewy-eyed clients danced their youth away. While they talked about perfume and films, a bald man with rosy lips approached them, looked at Rabea and said, “Can I have a request?”

“Let me guess, Britney Spears!” Rabea replied.

“Oh, come on Rabea, you are such a snob, you never accept my requests. It can’t all be niche music,” said the man with the nasally voice.

“It’s not me, it’s the management. But fine, la oyounak Najeeb, hit me baby one more time,” Rabea said.

Malek looked up from his phone and said, “Oh my god, Najeeb?”

“You two know each other?” Rabea said.

“He’s my childhood friend,” Najeeb yelled. He jumped on Malek, squeezed him tight and whispered in his ear, “I still have your iPod.”

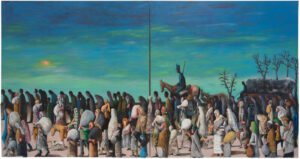

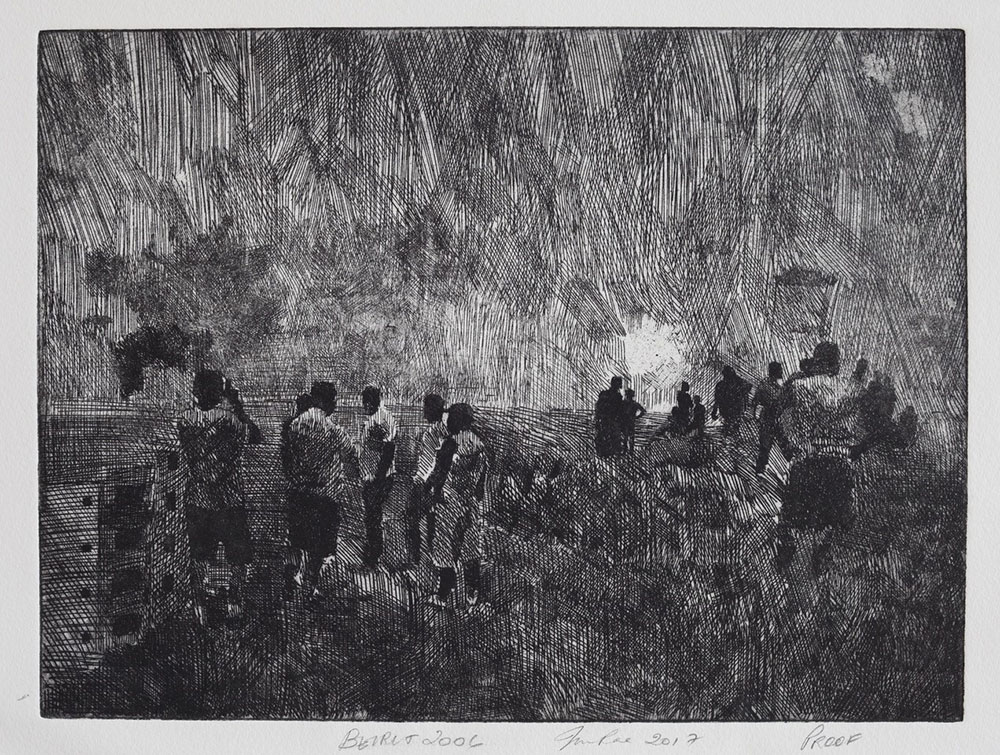

The IDF had been caught unaware by Hezbollah’s raid on northern Israel on July 11, 2006. Israel imposed a land, sea, and air blockade on Lebanon, and Israeli warplanes bombed Beirut’s international airport — resulting in thousands of deaths. The short story “The Summer They Heard Music” by MK Harb takes place during what became known as the 2006 Lebanon War.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)