A tale set in the near-future exploring the world of banned books, repressed imaginations, dreams, and desires.

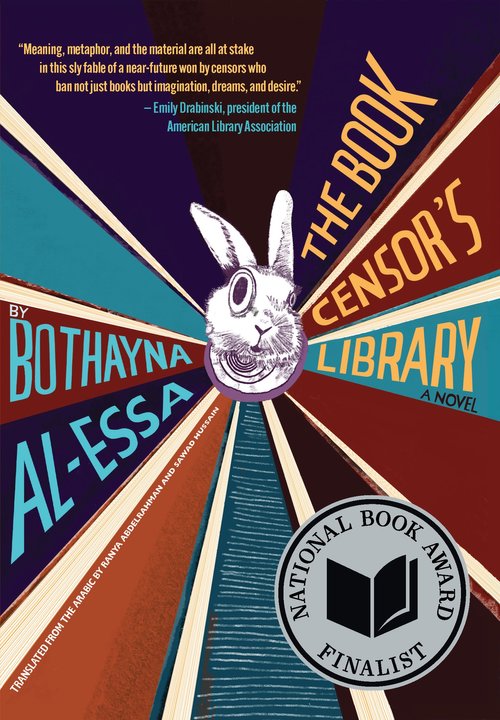

The Book Censor’s Library by Bothayna Al-Essa

Translated from the Arabic by Ranya Abdelrahman and Sawad Hussain

Restless Books 2024

ISBN 9781632063342

Bothayna Al-Essa is a self-described “bookworm” from Kuwait. Her novel, The Book Censor’s Library is an exploration of the world of banned books; ones that stir up trouble, threaten public order, offend society’s morals, and rattle the world’s confidence, as the author mentions in the novel. An award-winning novelist, Al-Essa is also the founder of the Takween bookstore and publishing house in Kuwait City, which since 2017 has introduced a range of celebrated Arabic titles. As a bookseller and author she is no stranger to the warped mindset of the censor. She was a vociferous advocate in the campaign against outlawing books in Kuwait, where in seven years’ time some 5,000 books were banned. Al-Essa and others lobbied the Kuwaiti National Assembly to amend the country’s publications and press laws. In 2020 the country lifted restrictions.

Her 13th novel, which won the Sharjah Award for Arab Creativity in 2021 and was translated by Ranya Abdelrahman and Sawad Hussain into English, was longlisted for the 2024 National Book Award for Translated Literature. The Book Censor’s Library is set in an unspecified country, in an unspecified time. As Al-Essa warns readers from the outset: “The events of this story happen sometime in the future, in a place that would be pointless to name, since it resembles every other place.”

An unnamed narrator enlisted by an oppressive government serves as its new book censor. He reviews novels to determine whether they should be approved or banned, particularly if they include forbidden themes related to the government, sexuality, and the internet. Additionally, any remnants of “Old World” religious beliefs, such as concepts of God, heaven, hell, and various rumors, also come under close scrutiny.

By portraying the struggles of the book censor and his associates as they navigate this terse landscape, the novel underscores the transformative power of literature in inspiring change, finding one’s voice, and ultimately fostering personal freedom. The novel’s protagonist, the book censor, comes face to face with questions at the heart of the process of banning books and thereby forbidding ideas: Do oppressive regimes fully understand the power of imagination? In their fear of creative expression and independent thinking, they impose strict measures to stifle creativity, worried that a vibrant and free spirit could ultimately challenge their control, as Bothayna Al-Essa’s narrator aptly observes:

Imagination had truly begun to shrivel and fade away, proving that if you control a human being’s circumstances, you can drive their development in a certain direction. You can encourage the existence of New Humans with no imagination and extremely limited desires, and without any pesky existential musings … the world was much simpler the way it was now.

The book censor and his seven colleagues, tasked with shutting down all avenues of literary interpretation, focus solely on the surface of language. In isolating words and phrases, they ensure that only the books that serve the government’s agenda are published in their country. Over time, the book censor reaches a profound realization: that the Censorship Authority “weren’t waging a war against books so much as against reading. Reading was a bad habit, but you couldn’t keep people from doing it, just as you couldn’t keep them from smoking or having sex. All you could do was limit their options, give them the illusion of choice. Then all on their own, they would turn away. In the future, he and the other censors wouldn’t need to ban any books — no one would read them anyway.”

When he’s given a new edition of Zorba the Greek destined for censorship, he unexpectedly finds himself captivated by its ideas. As he immerses himself deeper into the story, his view of reality begins to shift, leaving him ill-prepared to navigate his world where citizens are allowed only three fundamental desires: to belong, to procreate, and to work. Beyond these ideals of the state everything else is deemed toxic, unnecessary, and punishable by law. His awakening propels him from one book to another, until one morning he has a final epiphany: “filled with others’ words… [he is] transformed into a reader.”

If this secret comes to light, he risks being branded an enemy of the future, along with booksellers, book pirates, and readers. In the oppressive regime where he lives, he would be seen as a cancer — a traitor tainted by “the blood of Old World intellectuals in his veins.” If he gets caught, he would lose his job, face a shattered marriage, have his daughter taken from him, and see his freedom completely crushed because “at the end of the day, everything belonged to them” i.e. the System. As he overcomes his initial fear of stumbling upon an underground library, an unexpected sense of joy washes over him. He finds comfort in the realization that others, just like him, yearn for the solitude that comes with diving into their beloved books. This understanding reassures and reminds him that “he wasn’t all alone on the surface of the world, nor by himself beneath it.”

Life in the book censor’s home presents its own set of challenges. His five-year-old daughter displays concerning signs of an affliction: an overly vivid imagination that makes it hard for her to adjust to the System. She detests school where large murals of the President terrify her. She would much rather spend her day chatting with a make-believe wolf hidden in her wooden cupboard, or imagining tales of fairy dust and the boy who could fly, the wicked witch and magic shoes, and the poisoned apple too. “She was like a house possessed by spirits, the final doorway to the past,” finding greater joy in conversing with “any kind of creature — whether real or imaginary — as long as it wasn’t a human being.”

When things appear to be getting better at home, an unexpected visit to the book censor’s office turns everything upside down, raising the concerns of the little girl’s parents and intensifying their fears. The book censor and his wife are fully aware that if their daughter continues to struggle to fit into the System, someone from school or the neighborhood could tip off the authorities. This might lead to her being sent to a rehabilitation center designed to “cure” children like her of “Old World symptoms.” It’s a place from which few children ever return.

In recent years, book censorship has surged globally, driven by various factors including political oppression, cultural sensitivities, and the rise of authoritarian regimes. Many governments have been tightening their grip on literary expression, particularly targeting works that confront political narratives or delve into sensitive social issues. Countries like China, Turkey, and Hungary exemplify this trend with stringent state-sponsored censorship.

In the Middle East and North Africa censorship has been influenced by cultural and religious sensitivities, often resulting in the banning of books that explore themes of sexuality, religion, and personal freedoms. This backlash has led to self-censorship among authors and publishers, hindering the proliferation of progressive ideas.

In addition, the shift to digital platforms has not escaped the reach of censorship. Many governments are blocking access to websites and social media that support free expression, limiting independent publishers and literary organizations that engage with controversial works. Over the past decade, in Egypt, for example, censorship has become increasingly pronounced, reflecting a broader trend of tightening control over free expression and dissent. A significant factor in this rise of censorship is the political climate following the 2011 revolution in the country, which saw a brief period of increased freedom that was quickly reversed. Writers and publishers have faced crackdowns for perceived criticism of the government, religion, or the military. Several authors have been investigated or even imprisoned for their works, creating a chilling effect on literary expression. Moreover, educational censorship against young adult fiction with gender related themes is on the rise in the US, with various books challenged or banned in schools, igniting debates over academic freedom. Despite these developments, grassroots movements and resilient authors continue to fight against censorship. Advocacy organizations like PEN International and the American Library Association play a crucial role in highlighting cases of persecution and supporting the fight for free literary expression.

The Book Censor’s Library captures this ongoing global struggle. However, as the novel unfolds, it becomes clear that the literary references are exclusively drawn from the Western canon. This raises some intriguing questions: Why is there an absence of references to Arab, African, or Asian literature? Was the author attempting to familiarize Arab readers with the rich tapestry of Western literary canons, especially considering the novel was originally written in Arabic?

Or is it an ingenious opportunity to reflect the issue of censorship back onto the west, which has historically viewed the Global South as backward and mired in restrictions on free expression? This perspective acknowledges that many western nations grapple with their own forms of censorship and limitations on discourse. The irony lies in the fact that while the west criticizes the South as being overly restrictive, it, too, is afflicted by similar challenges, revealing a double standard in how free speech is valued and defended, particularly in the current discourse regarding the western media’s (lack of) reporting on the ongoing genocide in Gaza or (its repetition of triumphant Trumpisms on) the recent buster bombing of Iran. The novel’s narrative might have been further enhanced by grounding these elements in the author’s own cultural context. By doing so, a more meaningful cross-cultural exchange could have unfolded, ultimately deepening the appreciation and understanding of both literary canons. In the end, the book censor’s reasoning that “every story was a retelling of older ones and a harbinger of tales still to come,” will have to suffice.

Through her writing, Al Essa not only brings awareness to the issue of censorship but also inspires readers to reflect on the power of literature and the importance of defending diverse voices. Stories, she reminds us, are intricately woven into the very fabric of our being, reflecting the core of our identities. They shape our understanding of the world, bridge the cultural gaps, and serve as a profound means of connection. From timeless oral traditions to the vibrant landscape of modern digital storytelling, the narratives we share captivate not only our imaginations but also our hearts. They educate, inspire, and cultivate empathy, reminding us of our shared humanity.