François Thomazeau

La Rose du Ciel (The Rose of Heaven) is a lot like Marseille. It stands proud “between the crypt and the water,” as poet Paul Valéry wrote, on a cliff overlooking the old port. It is the perfect location to embrace the magic of the old cove around which Marseille was built. From the top floor, the Mediterranean glitters as far as the eye can see. And Marseille is all there: boats coming in, ferries going out, the old town with its bell towers and its forgotten windmills, its tiny town hall, the Fort Saint Jean and its stone walls, the MUCEM (Musée des civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée) and its lace of concrete. The house is overlooking the Marseille of today — the busy traffic moving along through the network tangle of tunnels tangled beneath the port — and the dwelling also rests upon the foundations of the city, the Saint Victor Abbey, founded in the 5th century. It could almost be a lighthouse. And yet it shies away from the curiosity of both tourists and locals.

Villa La Rose du Ciel, Maison Paul Valéry, 140 rue Sainte, Marseille (photos courtesy François Thomazeau).

Villa La Rose du Ciel, Maison Paul Valéry, 140 rue Sainte, Marseille (photos courtesy François Thomazeau).

You could be forgiven for missing it. If you came to the area, it was probably to see the Saint Victor Abbey with its fake medieval battlements and its crypts, which you can visit for 1.5 euros and discover the sarcophaguses of its founder monks as well as a cave supposed to have been the last home of Lazarus. He certainly never came anywhere near there, but Marseille is prone to exaggeration and loves to see itself as a city quite capable of rising from from the dead. Or you passed by Le Four des Navettes for the local pastry, navettes— boat-shaped biscuits so thick you should mind your teeth. On summer nights during the last decade, and before Covid-19 struck, the immediate surroundings of La Rose du Ciel became a hangout for thirty-somethings who, without a glance to the Rose of Heaven, came to down gallons of beer and eat tons of tapas on the pavement in front of the trendy Bar de l’Abbaye.

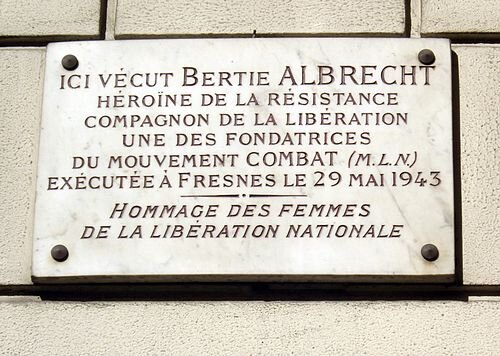

There is a little square adjacent to La Rose du Ciel, which might have been its garden, with a gorgeous view of the Carenage — the sector of the port where boats were once repaired. It is called Square Berty Albrecht, after one of the famous inhabitants of the Rose. Recently and between lockdowns, small open-air classical concerts take place in this square. But none of the musicians or spectators are likely to know who Berty Albrecht was. Maybe they had a quick glimpse at the plaque on the wall asserting that Paul Valéry once lived there. Beyond this, little do they know or care about the house.

And yet it is haunted, just as Marseille has been since the first-ever painting of a murder was splashed on the walls of the oldest cavern found off its shores, the Grotte Cosquer. Like most monuments in the city, the grotto is invisible. It lies under the sea. And even when such monuments are as visible as La Rose du Ciel, nobody sees them, or cares. The house is haunted by the memories of those who lived in it, their destinies as tragic, brilliant, diverse, obscure or remarkable as the city itself.

Picture yourself here, on the very spot where the abbey was built and later the house, like a little wart on its nose, at the beginning of the 5th century. It is the year 414, or perhaps 415, and you are standing on a rocky plateau above the port founded by the Greeks. The area is a huge cemetery, where the first Marseillais buried their dead, and the caves at your feet are the sepultures of Christians said to have been tortured to death by the Romans — Victor, the Christian soldier who gave his name to the abbey, or Lazarus, not the famous one but a priest who returned from Palestine with the first abbot, John Cassian, and several others. John Cassian spent years of imprisoned reclusion in Palestine and later in Egypt and was asked by the pope to bring his Near Eastern wisdom west and build two monasteries, one for men, one for women. He chose this holy spot and turned the burial site into an open-air baptistery, on top of which a chapel, a church, then a whole convent gradually rose. The influence of the abbey was considerable in the Christian world of the time and its monks and abbots spread the word of God around the Mediterranean from Spain to Italy. You would not imagine such a destiny nowadays by looking at the rather modest size of the church, but Marseille has always been discreet in terms of architecture, and today, two dull towers on the seafront can hardly be described as a “skyline.”

The abbey had its ups and downs. At times in the Middle Ages, it actually ruled the city and ran factories, mills, and priories all over Provence. It was also attacked, destroyed and plundered, notably by the Spaniards in 1423, when Marseille was almost annihilated. The troops of Aragon took home the chain that barred entry into the port and was probably tied to a pillar somewhere pretty close to where we stand. The chain is still in the cathedral of Valencia, and Marseille mayors have unsuccessfully asked for it to be handed back ever since.

“In Marseille, what is true is what is believed”

— François Thomazeau

In 17 centuries, several traditions took root around the abbey and are still extremely vivid. If you did stop at the bakery to buy navettes, you were perhaps told that their shape is supposed to evoke the boat that carried Mary Magdalene, Mary of Jacob, Mary Salome and Lazarus from Palestine to convert Provence in the 1st century. Others will tell you that the cake is in the shape of a womb and a reminder of a pagan fertility rite practiced on this spot. The navettes are baked on Candelma. On this day, a procession leads to the abbey, where the parishioners burn green candles in honour of the Black Virgin, a wooden statue of the Virgin Mary placed in a chapel next to the altar. Another version of the story says that the tradition is actually in honour of Saint Blaise, an Armenian priest martyred in the 4th century and whose arm — one of about fifteen held around churches throughout Europe — was kept in the crypt. Saint Blaise, who will rescue you if you call his name when a fishbone is stuck in your throat, was offered a cake and a green candle by a shepherdess he had protected against wolves. All these details need to be told, simply to make it clear that you are treading on holy land, standing as you are in front of the Rose of Heaven.

Little is known of the people who built this house, but it is a rather simple, rectangular block with a mansard roof of slates—which is rather uncommon in Marseille. It is a classic mid-19th century bourgeois townhouse with two palm-trees in the garden—another oddity in a city that has always refused to be a seaside resort. At its fronton, in a small niche, stands a bronze statue of a bearded man protecting a younger boy. Father and son, master and pupil? It is probably Joseph, and the boy a young Jesus.

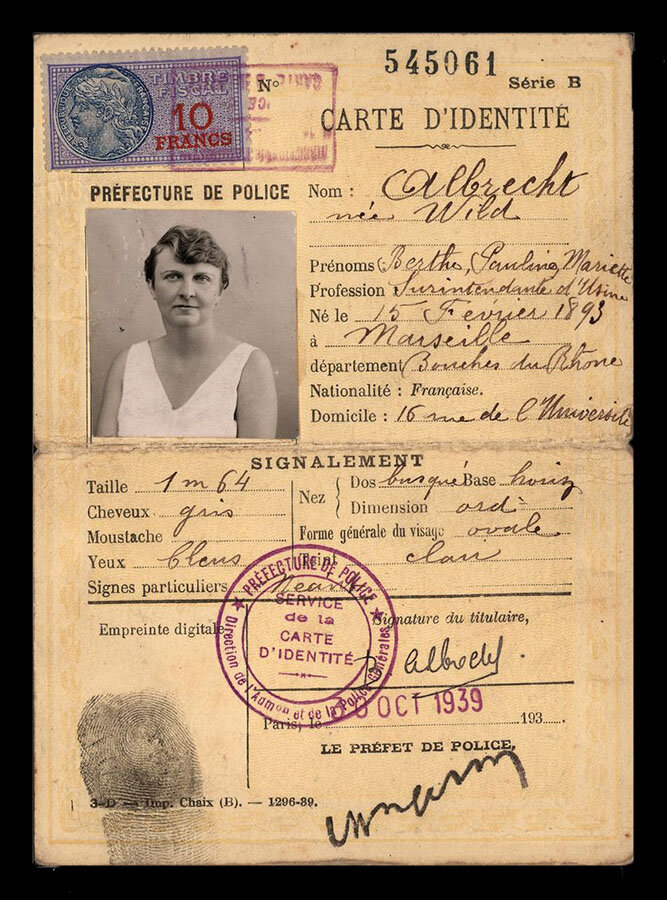

From the start, the Rose of Heaven was linked to the withdrawn but influential Protestant community of Marseille, many of them of Swiss origin. Among the first known tenants were apparently members of the Wild family, who lived there before WWI. Ulrich Wild was a trader in exotic wood. On Sundays, he often took his daughter Berty, born in 1893, to sea in the small boat he owned in the Vieux Port. Berty went to the town’s main high school for girls, Lycée Montgrand, and later studied to become a nurse in Lausanne. After receiving her degree in 1912, she returned to Marseille when the war broke out to work in a military hospital. The human suffering she witnessed had a lasting influence on her future life. At the end of the war, she married Frederic Albrecht, a Dutch banker who had worked with her father in his youth. The man was wealthy and in the 1920s, the couple settled in London, where they had two children.

But married life was not satisfactory for the passionate young mother, who started to attend lectures by feminist pioneer Sylvia Pankhurst, and soon Berty became a member of the Women’s Social and Political Union. She also befriended leftwing intellectuals like Bernard Shaw and Bertrand Russell and soon became involved in the birth control movement led by Mary Stopes. In 1931, she decided to take her children with her to Paris and part with her husband, who continued to pay for the education of his children. She joined the League of Human Rights and launched her own publication Le Problème Sexuel, defending the right of women to give birth when they wished and have a free sex life.

When the magazine collapsed in 1935, she became a social worker in factories while looking after Jewish refugees from Germany and Republican militants exiled by the Spanish War. After the French debacle of 1940, she refused to surrender and started, with her old friend Henry Frenay, a Resistance group called Les Petites Ailes, which was renamed Combat in 1942. Arrested twice by the Germans that year, she went on a hunger strike, and was sent to a mental hospital until she was freed by a group of comrades. Asked by other members of the Resistance to find shelter in London, she refused, continued the fight and was finally arrested by the Gestapo in May 1943, tortured and sent to Fresnes prison outside of Paris, where she was reportedly found hung in her cell. In 1945, her body was finally discovered in the garden of the prison, showing marks of strangulation. While male résistants like Jean Moulin became post-war heroes and mythical figures, Berty was only recently given the credit she amply deserved. During the war, she returned frequently to Marseille, where she had kept solid contacts, and maybe to the Rose of Heaven, or to the little square now bearing her name. Who knows?

By the time Berty was fighting the Nazis, the house had become the residence of Marguerite Fournier, the daughter of a local industry tycoon with a taste for the arts and social life. In 1937, she met Paul Valéry through friends she ran into by chance on a train and the poet became a regular visitor of the Rose. He called Marguerite “the abbess of St Victor” and he would spend hours on the house balcony watching the sea he now contemplates forever from the Cimetière Marin, the graveyard in which he is buried in Sète. Through her sister’s husband, Hippolyte Ebrard, a local scholar and novelist, Marguerite was close to the Marseille intelligentsia of the time and especially to Jean Ballard, the founder of a literary review, Les Cahiers du Sud, which published the leading French writers of the 1930s and 1940s from its headquarters on the View Port. When the war broke out and most of the inhabitants of northern France fled south, the Rose became a haven for artists in search of a place to stay or awaiting precious visas to flee to Spain or the United States.

Valéry lived at the Rose, of course, but also André Gide stayed here on his way to the Maghreb, as well as painter Rudolf Kundera, and pianists Marguerite Long, Samson François and Rudolf Firkusny often came to give improvised concerts. The abbess of St Victor also hosted composers Charles Munch, who had failed to find a hotel in the overcrowded port, and Bohuslav Martinu, who called her from a brothel where he had found refuge.

In fact Marseille, flocked with immigrants desperate for a way out of France, became for a year the cultural capital of the country and the Rose of Heaven one of its hot spots. In January 1942, the first rendition of Valéry’s Narcissus Cantata, conducted by composer Germaine Tailleferre, was broadcast on French National Radio from Marguerite’s house. Tailleferre left Marseille for America a few days later. Valéry also composed a piece called Mon Faust (My Faust) in Ebrard’s house in Cassis, a sort of twin house of the Rose of Heaven in Marseille. Was it fortuitous that the poet should have written a play about a man seeking eternal life in such an environment? France at the time was looking for resurrection. And remember Lazarus, the man who vanquished death, was supposedly buried in a cave beneath the abbey, almost beneath Marguerite’s house…

There is another tale about the Rose of Heaven which is far more cryptic and impossible to confirm. Marguerite’s in-law Ebrard was a Rosicrucian with a vast interest in the occult and he often met at dinners with Ballard, Valéry, and other artists to discuss alchemy and mysticism. The house was an ideal setting for such topics, given all the symbols and legends linked to the abbey — a crypt full of dead saints, a black virgin, green candles, and dodgy cakes. There were lots of double-entendres in the house itself with its statue of Joseph the carpenter and a name evoking Rosicrucianism.

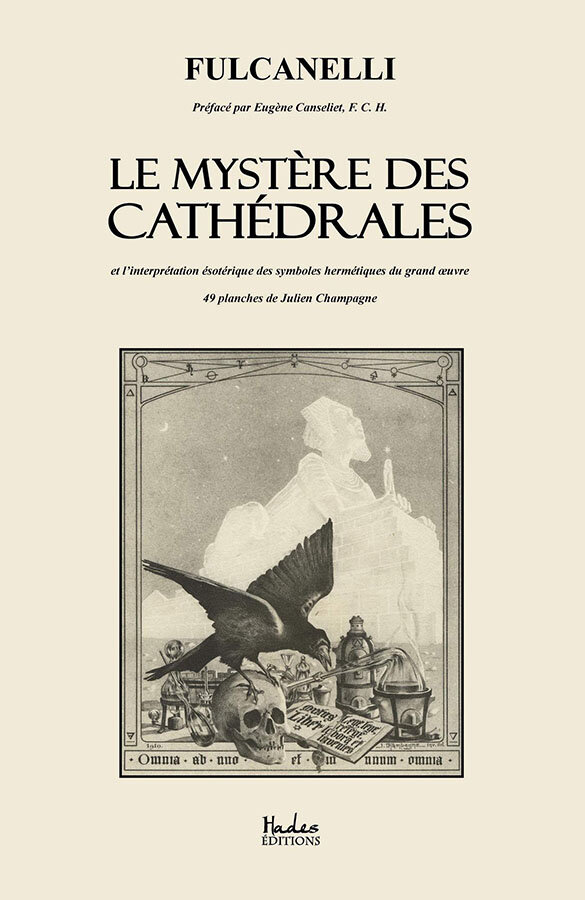

Some say the house might have been built to replace the rose window missing from the ancient church across the road. It is widely thought that in 1915 or 1916, Ebrard hosted in the Rose of Heaven one of the most mysterious occult writers of the 20th century, Fulcanelli. The esoteric author, who published two books in the 1920s, The Mystery of the Cathedrals and The Dwellings of the Philosophers, is said to have changed metal into gold and to have reached immortality — he has been seen in various places and times by his disciples to this day. In both of his works, the man whose identity has been debated for more than a century, mentioned the Saint Victor Abbey as full of alchemical symbols, and drawings by his illustrator Julien Champagne — who could be Fulcanelli himself — seem to have been done in the Rose of Heaven.

I said this was a haunted house. Now do you believe me?

Well, maybe you should not.

Home of Fake News

All the tales you just read are based on the most commonly accepted sources on Marseille history. And should you want to check the facts on various official websites about the city, you would probably believe them to be true. And they are not far from right. Yet Marseille is a town of lies, of make-believe, which even invented a word to describe its natural tendency to embellish: galéjades. This is a city that loves tales more than it loves truth, turns approximation into a fine art, and relishes the impression of reality rather than bare facts. In Marseille, what is true is what is believed. It is part of its charm that turns its entire history into an elaborate urban legend.

Closer enquiry reveals that the Lazarus buried in the crypt — local tales even pretend that he was tortured on the other side of the port and taken to the abbey by a secret tunnel built beneath the sea — was not the Biblical one but a 5th century priest who finally became bishop of Aix-en-Provence. There are no indications in her biographies that Berty Albrecht actually lived in the house standing next to the little square bearing her name. This fact was simply extrapolation from the locals. A bit of research reveals she actually lived at 125 rue Sainte, a bit up the road from the house. While Marguerite Fournier certainly lived at 140 rue Sainte, nothing proves that the house was ever called the Rose of Heaven. It seems that biographers and would-be historians confused the Marseille house with the one that Hippolyte Ebrard owned in Cassis and which is definitely called The Rose of Heaven. All the luminaries mentioned in fact did stay in either the house in Marseille now called La Rose du Ciel and in the house in Cassis rightly of this name. A 1913 painting by Irish artist Roderic O’Conor called “La Rose du Ciel, Cassis” provides evidence.

So should Marseille claim, on top of being the land of soap and bouillabaisse, to have been a pioneer of fake news? It does not really matter, does it? As long as you tell a good tale. Let me end with the most incredible story to have transpired in the area.

Not far from the Rose of Heaven — its given name now, rightly or wrongly — at the corner of Rue Sainte and Rue de la Paix, and back in the 17th century, once stood the Mosque of the Turks. France and the Ottoman authorities who ruled over the Maghreb at the time had agreed that their mutual prisoners should have a place of worship in Marseille and Istanbul. There was a Catholic chapel for the French detainees on the other side of the Mediterranean while a mosque was installed inside the Marseille Arsenal where the royal galleys were built by enslaved Muslims. When the arsenal was destroyed in 1748, so was the mosque. Yet parts of it reappeared here and there throughout the years. Vaults and pillars were first used to build a restaurant in a park just above the Saint Victor Abbey, Parc de la Colline Puget. When the restaurant folded in 1890, the ruins of the mosque vanished once again. They were apparently reused to build a house on rue Paradis (!) but as the house was reputedly haunted (again!), it was destroyed in the 1920s. What remained of the mosque was purchased by a rich industrialist, Paul Rouvière. He used the vestiges to build a mausoleum for his children, who drowned while swimming off the shore of Bandol in 1927. The building is still standing outside of his now demolished house, in a public park known as Parc Valbelle, not far from Prado beach. It is officially listed by the French Culture Ministry as “the former Mosque of the Turks.” If so, it would probably be the oldest mosque in Western Europe! Yet it stands in an almost empty park, with old ladies and their doggies as its only faithful. Now is it really the Mosque of the Turks? Maybe. Maybe not. Who cares?

Epilogue

A few years ago, as I was walking past the Rose of Heaven in Marseille, I noticed that a poster with a phone number on it had been pinned to one of the windows. FOR SALE. I hurriedly called the number to find out what it was about. An old lady replied to my call and gave me a price I actually could have afforded. “Oh, but you’re very unlucky. The house was sold only an hour ago,” she said.

I too nearly lived in the Rose of Heaven.

This is absolutely fabulous, thank you. I shall be visiting Marseille from my home in Japan, and now I know where my first stop will be… a corner of the fascinating world that is the mind of FT! And to think I landed here because of Doncaster and a bicycle race! “Marseille is a town of lies, of make-believe, which even invented a word to describe its natural tendency to embellish: galéjades. This is a city that loves tales more than it loves truth, turns approximation into a fine art, and relishes the impression of reality rather than bare facts. In Marseille, what is true is what is believed. It is part of its charm that turns its entire history into an elaborate urban legend.”. How could I not ne intrigued?