Syrian Asylees in the US want to go home. They could be risking everything.

Some names in this story have been changed to protect the identities of the subjects.

Sam always said that the second Bashar al-Assad’s regime fell, he would be on the first flight home to Damascus. But during the days leading up to the fall of the former Syrian president, Sam sat on the beaches of San Juan, Puerto Rico, with his eyes glued to his phone screen.

Sam, a Syrian asylee now living in the United States, had traveled to Puerto Rico for his friend’s birthday, and as he, his friend and her boyfriend — all Syrians — scrolled through text messages, news clips and videos of the scene in Syria, the San Juan sun beat down on their skin. All Sam could think about was how much he regretted booking a vacation during this pivotal moment in history, but at least he was surrounded by Syrian friends who could understand what this meant.

Finally, on Dec. 8, 2024, the rebels claimed Damascus. Assad fled to Moscow, marking the end of a family dynasty, a dictatorship that had devastated Syria for over 50 years. The Puerto Rico crew rejoiced by singing revolution songs at a near-empty karaoke bar for hours into the night, chanting Arabic lyrics like, “Leave us, you liar / Enough wounded and suffering / Freedom is at the door / Whoever kills his own people is a traitor.”

“ Never in my entire life have I felt any joy compared to that day. Never. Not even close. The euphoria, the crying, the phone ringing nonstop,” Sam recalled.

His happiness, however, faded soon after he returned to New York. Many of his other Syrian friends were booking flights home, but Sam feared the shifting political climate in the U.S. He’d fled Syria as an asylum seeker, and though he now holds a green card, the incoming Trump administration was vowing to make good on its promises to deport millions of immigrants, even legal residents. If he got on a plane to Syria, would he be allowed to return to the United States? It felt like a betrayal to the promise he’d made to himself and others for as long as he could remember; to him, he said it almost feels like a “double exile.”

“When people were going, I was losing my mind,” he said. “I was like, ‘How the fuck do I make it there immediately?’ Like, I need to be there right now.”

When the Assad regime fell, Syrians all around the world let out a breath they’d been holding for over five decades. After much tearful rejoicing, many of those who’d been exiled for publicly opposing the regime decided to return to their homeland for the first time in years, a feat deemed impossible so long as the dictatorship remained. Now, the United Nations Refugee Agency has reported that over 300,000 Syrian refugees worldwide have already traveled back home since Dec. 8. But for some Syrian communities in the U.S., that excitement has been tempered by fear, with the Trump administration’s targeting of immigrants and legal U.S. residents leaving them uncertain about being able to return.

“Everyone has those questions, like people who’ve had their cases pending forever are now thinking, ‘will it be possible for me to go back?’” said Nadeen Aljijakli, an immigration lawyer who primarily works with Syrian asylum seekers. “And there are people who are just extremely terrified, whose asylum cases are pending, or they have upcoming court dates where their asylum cases will be assessed, and we’re trying to figure out how best to support those cases.”

According to the Migration Policy Institute, 27,900 Syrian refugees resettled in the United States between the fiscal years of 2012 and 2022. In 2024 alone, another 11,274 arrived in the U.S., as reported by Refugee Council USA, making up just over ten percent of the total number of refugees brought to the U.S. that year. While it is unclear how many U.S-based Syrian refugees and asylees have made their way back to Syria since the fall of the regime, Aljijakli said the increased risks that they must consider are seemingly already being felt.

“We’ve heard reports that some of those cases where people had that specific kind of protection [asylees and green card holders], are being reopened, the government saying, ‘Oh, now you’re good. Now you’re no longer in danger and we can deport you back to Syria,’” Aljijakli said. “So we’re just starting to hear anecdotally some reports around the country of things like that happening, so there may be more and more of a shift in that direction in the next year.”

Sam now finds himself stuck in an impossible and frustrating situation.

“To be very frank, there’s a part of me that feels like, fuck it, let them revoke [my green card]. Because what is this? I mean, I’ve been a very good citizen for this country for over 11 years — I know that for a fact. I have all the proof to say that, yet I’ve not been treated like a good citizen. And if my opinions or the fact that I wanna visit a country that just lost its dictator after all these years could pose a threat to my existence here, then maybe I should revisit if I want to exist here,” Sam said.

Sam was born and raised in Damascus, growing up in a middle-class family that emphasized the importance of education and cultural expression. Politics were not often discussed outside the home, but a strong sense of political awareness about what was happening within the Arab world was imparted to Sam and his younger sister at an early age.

Artistically inclined, Sam attended music and theater activities alongside his studies before enrolling at the University of Kalamoon, a private institution about 50 miles north of Damascus, where he studied art.

The Syrian revolution began to coalesce shortly after Sam entered university. “By the time I went to college, educational systems were sort of screwed. I feel like I learned everything I needed to learn after college, not in college,” he said.

Classes were frequently canceled due to dangerous conditions. Students and faculty would rush to hide at the sounds of bombs dropping nearby. Protests in opposition to the Assad regime broke out frequently, oftentimes ending in bloodshed and casualties.

In 2012, when Sam was 19, he took part in his first and only protest in support of the revolution. The demonstration was so violently suppressed by the Assad militants that a traumatized Sam vowed never to attend another one again.

“I saw arrests happening at the dormitory. And I went through the buildings and I kept seeing broken glass and blood everywhere. And then when I reached the art school, I realized that they were all there — people were hiding in the art school,” he said.

Sam’s phone was searched for any evidence or documentation of the protest, and students were locked in on campus for hours until the regime had finished their arrests. In the following days, Sam’s father, who worked as a lawyer, would be detained by the Assad regime for reasons that remain unclear to this day. Perhaps his emails discussing the revolution were intercepted, or maybe an adversary from a lawsuit he had won had reported him to the regime in retaliation. Whatever had happened, Sam’s family could no longer stay under the radar.

“I was the most scared when my dad was detained, because at that point, you know that the regime forces are after you — they have your names, they’re watching what you’re doing,” Sam said. For a family that had carefully avoided the regime’s line of sight for decades, Sam’s father’s detention would change everything.

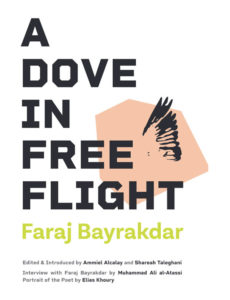

Following his traumatic protesting experience, Sam decided to channel his activism into other forms. He helped Syrians wanting to leave file visa applications, volunteered at refugee schools and wrote anonymously about the revolution, among other activities.

“I was 19 and I felt like I don’t want to be involved in this, so I sort of just stayed away and read, translated things here and there. That was my activism,” he said. “Was I pro-revolution? Very much so, of course. But I was also dead scared.”

His parents, on the other hand, were more heavily involved in revolutionary activities. Sam’s mother, who worked in education, offered volunteer support at schools and refugee sites, helping displaced families affected by the bombings around Damascus flee from danger and sneaking medicine to areas that had been besieged by the regime. She and Sam’s father were both detained at different times, which frightened Sam even more.

After his father’s detainment in 2012, Sam and his family knew they could no longer stay in Syria. Those who openly protested the Assad regime were increasingly met with violence, interrogation, persecution and death, and many were forced to leave the country and seek refuge elsewhere for their own safety. Those who could not escape or chose to stay had to endure poor living conditions, such as unreliable access to electricity, an overwhelming 90 percent poverty rate, debilitating destruction, pollution and the general sense of fear that loomed over the country.

“I think fear was a major characteristic of life under the Assad regime from the beginning until the end, and indignities — the fact that those in power could basically do whatever they wanted without any sort of accountability, with total impunity, and citizens had no recourse, no rights, no way to defend themselves and protect their own rights,” said Wendy Pearlman, a political science professor at Northwestern University. “Some people risk their lives to protest. Some people try to put their heads down and survive and get along.”

Sam’s family began researching visa applications and renewing their passports so that they could join his uncle in Fort Worth, Texas. In 2014, Sam, his mother and his sister were successfully able to obtain tourist visas to enter the United States, which Sam said might have likely been made more possible by his family’s financial status.

“People who have the means, or somehow have the connections to get through that last category of processes, the visas and the family members — I’m making generalizations, but they will often maybe be socioeconomically better off than the people who sort of sit in a Lebanese camp for five years before making it through the resettlement process that itself takes two years,” said Rana Khoury, an assistant political science professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

The plan was to claim asylum as soon as they arrived in the U.S. Sam’s father joined them briefly, but after returning to Syria to check on his extended family, he was detained once again at the Syrian border (he was later released) and has been separated from his wife and children for over a decade.

The family’s asylum case interviews took place in 2019, five years after their initial claims. The were all interviewed separately, with Sam going first, and his mother and sister about a month later. It took a year for Sam’s case to be approved, after which he could begin his green card application and his path toward U.S. citizenship. His mother and sister, however, would not hear back about their cases until the end of March 2025, six years after their interviews and over 10 years after first arriving in the U.S.

“There’s a sense of safety and relief that now they can be on a path where they can apply for a green card after a year, and after four years perhaps apply for citizenship,” Sam said.

Living in Texas, Sam assumed much of the responsibility for taking care of his family; his mother did not speak English and his sister was still in high school, so it was up to him to figure out how to build a new life for them in the United States. He picked up a number of odd jobs to support himself and his family, like driving for Lyft and Uber (where he started going by the name Sam after he noticed riders would often cancel their trips when they saw his name) and working as a butcher at an Arab grocery store. He was able to continue building upon his artistic interests by working as a graphic designer, a theater production assistant and for various art galleries.

But deep down, Sam knew he didn’t belong in the Lone Star State, where the vast number of highways and reliance on cars to get around depressed him deeply. “It just physically and mentally destroyed me. I know it sounds crazy, but I’ve done the analysis: I need to walk, I need to see people, I need to navigate the city, I need to be with it in a way,” he said.

Sam set his sights on New York, a city full of artistic expression that reminded him more of the Syrian home he had grown up in than Fort Worth ever would. Wanting to go back to school and continue his education, Sam applied to several universities, but was unsuccessful in getting any admission offers. Not willing to give up, he tried applying for various art gallery and museum positions, and in 2022, he permanently relocated to the city after accepting a curational role at a major museum, where he currently works today.

“I complained a lot about the city [Fort Worth] urban style, but also, I was after a Syrian community, and they’re all here — the ones I’m interested in, the ones my age or my group age that were part of the revolution,” he said. “We come from very different places and backgrounds. I think if we were all still in Syria, we might have had different friends, but that also makes it interesting. I think we’re like friends of exile.”

Despite living over five thousand miles away, Sam, now 31, keeps Syria present around him in various ways. His apartment in Inwood smells of jasmine and is decorated with Syrian keepsakes, books and photographs from wall to wall. A framed photo he took in Damascus hangs on his living room wall, with the blur of city lights watched over by the silhouette of Mount Qasioun in the distance. He keeps a drawer filled with the outgrown clothes he used to wear when he lived in Syria; he can’t bear to give them away.

“There’s no place I love more than Syria. There are no people I love more than Syrians. It’s been 11 years, but the way I feel connected to the place and the city and the culture is innate,” he said.

Which is precisely why it agonizes him that after years of waiting in exile, Sam still cannot return — except now for different reasons. In order to feel safe and secure enough to travel back to Syria, Sam needs two things. The first: his refugee travel document, which would act in lieu of a Syrian passport. (His passport expired in 2015 and was never renewed given the lack of an active Syrian embassy in the U.S. since 2014). In January 2025, just weeks after the fall of Assad’s regime, he applied for the refugee travel document.

The second thing he needs is guaranteed re-entry into the U.S. following his return. The terms of the document would ostensibly allow him, as a green card holder, to re-enter the U.S. after his travels, leaving Sam free to return to Syria, even if just for a week, to reunite with his now 61-year-old father and witness for himself what’s become of his birth country. But in reality, the question remains: by returning to the country an asylee initially sought refuge from, does the U.S. have the grounds to challenge their need for protection moving forward? In today’s political landscape in the United States, where legal U.S. residents and immigrants are being detained and threatened with deportation left and right for reasons that many judges and lawyers are deeming unconstitutional, perhaps it’s not a matter of if the U.S. can legally do it, but only whether they might bother with it at all.

“The situation in Syria is unique in that the country’s conditions have changed,” said Aljijakli, “which makes things even more complicated. So you could say as an asylee, ‘Yeah, there wasn’t any fraud [in their asylum application], but the country conditions have changed, and that is why I went back.’ But then that brings the next question, which is, okay, well then do you still need this protection as an asylee? And it could start the process of the U.S. government either denying the pending asylum application or trying to take asylum status away. [Asylees] are somewhat more protected if they’re already green card holders. That status is more secure, and the risk is less, but at any point, the U.S. government — even if [the person has] a green card — can look at their status and try to challenge it if they came in as asylees.”

In general, Aljijakli said she’s advising her Syrian clients not to risk travelling back to Syria at the moment because of the heightened hostility from the Trump administration vis-a-vis asylum seekers, whether or not they hold a green card.

“If they received their green card based on their asylum case, then we absolutely would avoid travel to Syria, because that’s a big red flag,” she said.

This leaves U.S.-based asylees and refugees, many of whom have not been back to their home countries in over a decade, in a discouraging predicament. They must now decide whether the chance to go home for a visit is worth risking the entire life they worked to build in the U.S. over the last decade or more of exile. Sam likes the life he’s created in New York, as does his mother in Texas and his sister in Albuquerque, New Mexico, where she currently works as a paramedic. Sam will be eligible to apply for U.S. citizenship next year, which he plans on doing. None of his family necessarily want to move back to Syria, but the ability to safely set foot on Syrian ground again would bring them much peace of mind.

“Asylum seeking, just like in the U.S., has become such a very politicized and sort of weaponized issue in the domestic politics of these countries,” Khoury said, “and so it really depends on somebody’s specific legal status in this moment. Some people might have even achieved citizenship — for them, they should be able to be mobile, right? But if your legal status is still in the gray area, you’re still in the middle of some process, you don’t – for the most part, for most places – you don’t enjoy mobility.”

Khoury also argues however, that asylees need to be granted the option by their governments to at least evaluate the situation in their countries before making a decision to permanently resettle. “They need to see the situation of their homes, of their neighborhoods, of the services available, of the possibilities,” she said. “The decision is very difficult, and the least that any host state can do is allow people to go and come back to be able to see and gather the information they need to make this huge decision.”

Some countries with large populations of displaced Syrians have put “go-and-see” policies into place following the end of the Assad regime to encourage their Syrian refugees to travel temporarily and assess the situation before making a decision. Türkiye, for example, allows one adult per Syrian family to visit the country and return up to three times within six months without risking their protected status.

“It’s such an important move. It’s like the most minimal humanitarian gesture for people who’ve suffered,” Pearlman said.

Five decades of a repressive regime has left Syria debilitated and deeply in need of reform and reconstruction — not to mention healing. Over 14 million people have been displaced from their homes, and an estimated 600,000 plus civilians have lost their lives since the beginning of the Syrian civil war in 2011. Today, the country still faces waves of instability and tension in the midst of this transition, and with many outside countries still imposing sanctions on Syria and withholding humanitarian aid, reform and rebuilding is that much harder. The fear that consumed Syrians under Assad’s rule may have all but dissipated, but to Aljijakli, it only continues to grow in the U.S.

“I’m trying my best through our firm not to be alarmist or to catastrophize everything that’s happening,” she said, “but it is very concerning in terms of what the government is doing and the hostile environment it’s created toward not only immigrants, but also the immigration attorneys that represent them and to U.S. citizens as well. This is a time to be more cautious than ever.”

But Sam would like the opportunity to help the Syrian people in any way he can, so much so that he’s even flirted with the idea of trying to enter Syria through Lebanon or Jordan using his Syrian documents, which in no way would make for an easier or safer journey. Still — the desperation sometimes leads to the most outlandish ideas.

“Even if I do that, it’s a risk, because when I come back here, they’re going to be like, ‘Why did you go to your refugee country?’ I have friends who did it, and they were not asked, but is it not risky? It’s risky.”

For the time being, Sam must live vicariously through the friends and family who have managed to make the journey back to Syria, including his partner of four years — who claimed asylum in France and has since obtained citizenship — whose family lives in Aleppo. Seeing pictures of his partner in Damascus and watching them enjoy being back in Syria was enough to ease Sam’s anger and frustration.

“It felt validating that I’m not crazy, because you do have to ask yourself that when you know people there that are struggling and are dying to leave this country that’s giving them nothing, why the fuck can I not stop thinking about it? Why is it hurting me this much where obviously I have a life that they all wish to have? There’s no answer to that. It’s just home, and you cannot shake the love of home.”

As Sam continues to struggle with the idea that his return to Syria might still be just out of reach, he chooses to remind himself of the things he most looks forward to experiencing again to take him out of his depression and into a more hopeful state of mind.

“All that kept me going was the joy of fantasizing about walking again in Old Damascus. That’s all I want. That is literally all I want. I want to be in Old Damascus for two, three days, and just not talk to anyone — just do it my own way,” he said. “That’s what I did when I was a teenager, and it’s the ultimate joy.”