The Majority of Other Countries Offer the Hope of Release

Opinions published in The Markaz Review reflect the perspective of their authors and do not necessarily represent TMR.

Stephen Rohde

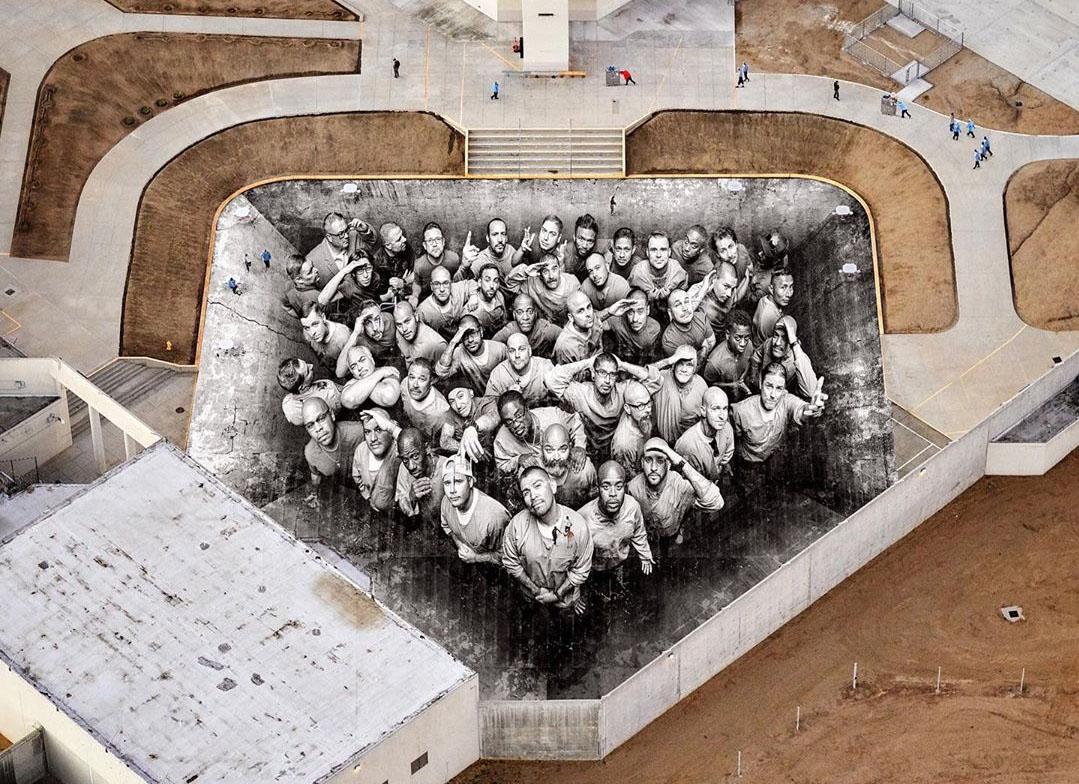

As the movement to end the death penalty in the United States gains momentum — two-thirds of the states (36 out of 50) have either abolished capital punishment or conducted no executions in at least 10 years — serious attention is being paid to Life Imprisonment Without Parole (LWOP), which is on the books in every state, except Alaska. In the 27 states that have retained capital punishment, the only alternative sentence is LWOP.

Is it inhumane, cruel, and unusual to sentence someone to prison for the rest of his or her life without any possibility of being released, especially when the inmate has exhibited genuine remorse and has demonstrated the capacity to lead a productive and law-abiding life outside prison? As with other features of the U.S. criminal legal system, there is much we can learn from countries that have abolished capital punishment, in terms of how they apply alternative forms of punishment.

Life Imprisonment With Parole (LWP), where release is routinely considered by a court, parole board, or similar body, is the most common type of life imprisonment in the world, according to research conducted by Dr. Catherine Appleton and Professor Dirk van Zyl Smit of the Life Imprisonment Worldwide Revisited project at the University of Nottingham (on which the data in this article is based). In 144 of the 183 countries (79 per cent) that were identified as having formal life imprisonment, there is no LWOP; there is always some provision for release, even for the most heinous crimes.

The US is an outlier. More than 50 per cent of all prisoners serving LWOP around the world are in the US. 22 US states even impose LWOP for non-violent offenses. While LWOP has been abolished in most European countries, it has recently been adopted in India and China, both of whom also have the death penalty. That is the company the US keeps.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child expressly prohibits LWOP for children. Although every other country in the world is a signatory to the Convention, the US is not. On the contrary, the US Supreme Court has ruled that LWOP may be imposed on children in “very exceptional” cases, provided there is some kind of review from time to time.

Appleton and van Zyl Smit have also gathered data on statutory minimum terms in 98 countries where LWP is imposed. The average minimum was 18.3 years. 29 countries (30 per cent) set their minimum period at 25 years or more while in almost half (46 per cent) the minimum period was 15 years or less.

According to Appleton and van Zyl Smit, research shows the severe psychological and sociological damage caused by a life sentence, with inmates describing “a tunnel without light at the end” and “a slow, torturous death.” LWOP prisoners express a profound and growing sense of loss and loneliness and the realization that many family members will most likely die while they are in prison. To add insult to injury, since LWOP prisoners will never be released, they are deprived of any rehabilitative opportunities, leading to sheer hopelessness and mental deterioration. In the US, many LWOP prisoners, including children, are denied access to educational and vocational training, based on the maddening premise that they are beyond redemption.

Meanwhile, a growing body of evidence from different countries indicates that recidivism and re-arrest rates among released life-sentenced prisoners are low compared to other released prisoners. Research examined by Appleton and van Zyl Smit shows that very few released life-sentenced prisoners commit further crimes and that, despite facing significant barriers, they are able to resettle successfully, especially when they are provided with programs and supervision in the community that support new non-criminal, pro-social identities, a strong sense of self-efficacy and responsibility, and a determination to succeed.

A UN report in 1994 concluded that life imprisonment should be “imposed only when strictly needed to protect society and ensure justice, and…only on individuals who have committed the most serious crimes.” It noted that “it is essential to consider the potentially detrimental effects of life imprisonment.” The report proposed that countries should provide a possibility of parole for all persons sentenced to life imprisonment, including those convicted of murder.

In 2013, the European Court of Human Rights held that it is a violation of human dignity to deny life prisoners any prospect of release or review of their sentence. The three applicants in the case of Vinter v. United Kingdom were each convicted of murder in the UK and were sentenced to “whole life,” that is LWOP. They argued that their sentences were inconsistent with Article 3 of the European Convention of Human Rights which provides that “no one shall be subjected to torture or to inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” While the lower court held life imprisonment was justified by the legitimate goals of punishment and deterrence, the Court’s appellate Grand Chamber held (by 16 votes to one) that an irreducible life sentences may infringe Article 3 since the review of a sentence is necessary because the grounds for detention (punishment, deterrence, public protection and rehabilitation) may change during lengthy imprisonment. The Grand Chamber noted the support in European domestic and international law for a guaranteed review within the first 25 years of a sentence.

The ruling noted that a prospect of release is necessary because the weight of European and international law supports the principle that all prisoners, including those serving life sentences, be offered the possibility of rehabilitation and the possibility of release if rehabilitation is achieved. Drawing on these sources, the Grand Chamber concluded that it would be a violation of human dignity to detain someone without any chance of release.

One commentator indicated that the Vinter decision “catalogues a global consensus on the proper goals of detention. Among many citations to international documents, the Grand Chamber referred to Council of Europe materials, the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). From these it evidenced a consensus in international law that the rehabilitation of offenders should be a key aim of penal detention.” Reducibility does not mean that a life sentence must actually be reduced when a prisoner remains dangerous. But it violates human dignity to deny life prisoners even a faint hope of release.

Article 10(1) of the ICCPR states that “All deprived of their liberty shall be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person,” and Article 10(3) states that the purpose of the penitentiary system is the “reformation and social rehabilitation” of prisoners. It indicates that every prisoner should have the opportunity to be rehabilitated back into society and lead law-abiding and self-supporting lives, even those convicted of the most serious offences. Similarly, Article 110(3) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court does not allow LWOP sentences, and instead calls for a mandatory review of life sentences after 25 years. The United Nations Handbook on the Management of High-Risk Prisoners underlines the need to approach the management of dangerous or high-risk prisoners in a positive, humane and progressive manner.

At a regional level, the Council of Europe has been the most active body in developing recommendations for the treatment and management of life and long-term prisoners. It states that the aims of life and long-term prison regimes should be (i) “to ensure that prisons are safe and secure places for these prisoners and for all those who work with or visit them”; (ii) “to counteract the damaging effects of life and long-term imprisonment”; and (iii) “to increase and improve the possibilities for these prisoners to be successfully resettled in society and to lead a law-abiding life following their release.”

It is high time the US seriously examine the widespread use of LWOP through the lens of the humanitarian principles of international law which recognize the transcendence of human dignity and the capacity for rehabilitation in every person, including those who have committed heinous crimes. Just as the US is finally beginning to see the flaws and cruelty of executions, it cannot ignore the inhumanity of the “slow, torturous death” of life imprisonment without any hope of release.

The views expressed in this article are Stephen Rohde’s and are not made on behalf of any organization. Mr. Rohde would like to thank Ines Horta Pinto, PhD in Criminal Law from the University of Coimbra, Portugal, for assisting in the research for this article.

Apoyo que se realicen y se apege ala ley para que resivan estos beneficios alos presos que ahorita estan en las prisiones estadounidenses