After the war, a few scant survivors become one with the elements, and one takes to writing down thousands of words a day in an invented language.

Mansoura Ez-Eldin

Translated from the Arabic by Lina Mounzer

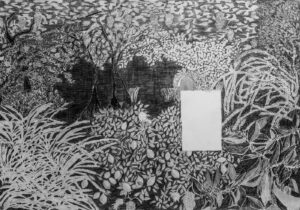

I was chopping wood in the forest beside my hut when the feeling overcame me for the first time, or rather, when I first put my finger on it, saw it for what it was. It’s been with me for as long as I can remember, but it only materialized at that moment, when I was surrounded by trunks, cut branches and fallen leaves.

I felt as though I were a creature made of wood. Saturated by its smell. Overwhelmed by it, my soul overtaken. I’m enchanted by its freshness. Surrounded by it, I feel as though I were inside my home, that first, most primal home whose memory has escaped me, but whose smells and sounds remain deep within.

In this I found an explanation for all my actions since I’d left my old house and moved to this remote spot, where chopping wood has become a daily habit. A ritual from which nothing can distract me. I started spending most of my time sanding dead wood and carving it into pieces of furniture or tools I didn’t really need. My favorite times were those I spent with my hands in contact with that raw material, granting it form that it would have never attained without me. The act takes up all my attention and leaves me no time to think about the reality surrounding me, which is nothing more than emptiness, void, and silence, broken — from time to time — by barking or howling or some din whose origin is difficult to identify.

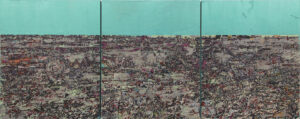

When I finish, I wander around the city. I pass by all the abandoned houses to make sure they’re still there. Their owners abandoned most of them so hastily they didn’t even close the doors behind them. I examine the details of every house, fighting my allergies at all the accumulated layers of dust. I open the windows to air out the space, then I close them again before leaving. I admire the chaos of kitchen gardens on their way to turning into miniature jungles, and I don’t attempt any intervention to stop them. My battle against nature is doomed to failure and so I leave it (nature, not the battle) to take its course. I watch over its incursion, spying on it from afar. I’m not even in the mood to fight for the space my own body occupies. In my current state, I feel as though I’m only existing, not living. I breathe and eat and sleep and wake up regardless. And apart from my wanderings from one end of the city to the other and my obsession with carpentry, I don’t do anything of significance.

If it weren’t for the fruit trees and the profusion of mushrooms in the woods I would have perished, along with my two companions. I’m the only one who realizes this as they are each lost in their own world. They hardly notice when I leave some food next to them. I don’t actually know if they eat it nor not. I deduce that they do only for two reasons. The first is that they remain alive, and the second is that there’s no trace of food left when I come back the next day. If the birds had pecked at it they would have no doubt left some scattered crumbs behind.

I don’t stop to consider the matter for long. Unthinkingly, I continue to provide them with food and water, hoping that one day they awaken to who they once were, even if part of me fears that awakening, because I don’t know how I’ll explain how the world became so devastated.

I think there’s something in my past decisions that brought me to this state: a drifter wandering the streets, overwhelmed by some memories so clear and present they seem as though they were still unfolding, and longing for others that have all but disappeared, leaving behind only an all-encompassing feeling of loss.

I’d burned all my bridges, and vowed that I’d never again budge from my place or change anything about it. It was good to content myself with being a silent watcher for some time. Exciting to withdraw and give myself over like a feather to the wind, leaving the world to its chaos, without which it would have no meaning.

Nor would I allow myself to abandon my two companions, though I knew — deep down — that there was more to it than that. I would have stayed even if I were the only one here. There’s rubble in my heart, and ruin lurking in my soul, and so I’m bound to see destruction reflected before me wherever I go.

I drift through winding streets, gazing at horizons that reveal nothing and at an ever-cloudy sky. The relentless vertigo doesn’t bother me anymore. I’ve adapted to it. I used to be surprised when I ran into one of those who stayed here, with their unfocused eyes and dizzy spirits and bodies unable to handle the constant swaying. I expected them to leave in time, which is in fact what happened. They all disappeared, one after the other. The place emptied out, except for the three of us.

I walk from one spot to another without having to think about or even look to see where I’m going. The city is tattooed on my heart, carved into the grooves of my brain, onto my bones, its overlapping streets and squares flimsy as spiderwebs, its surrounding forest like a bracelet constricting a wrist. I’m always careful not to pass near my old house. I can’t bear the sight of bullet holes in its walls anymore, or the massive shell hole in the building across from it. Since I fled, I haven’t gone near it. I don’t even think of taking my things back to my hut, a hut whose wood I cut down in some kind of trance and built the way one weaves a dress from threads of love.

In my hut I expend my days in a state of calm untroubled by anything except the awareness that there’s someone waiting for me, counting on me, even if only from inside their own hallucinations. I’ve grown tired of this; I long for a life without responsibilities or demands. I grow anxious at the mere thought of the existence of others beyond the boundaries of my own body. It’s enough having to deal with those that inhabit me and wrestle inside me. Sometimes I pretend that this city belongs to me alone. No one else is in it, and no one has ever lived in it or crossed its streets save for me. Every once in a while, I’ll succeed in convincing myself of this, but more often than not my eyes and memory betray the lie.

I reach the northern outskirts of the city, where the cactus fields display cacti of every shape and color. I see him lying there among the ovoid plants, barely able to raise his head, and I know that, as usual, he’s managed to numb his mind and senses. I don’t try to approach him; I leave him to his imagination and dreams. I’m not ready to pay the price of awakening him, alerting him. I’m not in the mood to endure a torrent of complaints and wailing and agony shouted into the void. Whether I like it or not, I’m no longer anything but a void to him. He gives me incoherent phrases, about a river he’s down at the bottom of, about a lake of mercury, and an oasis it’s difficult to leave. I shake his words off, but the idea of the river and the lake and the oasis remains lodged in my imagination.

I leave him, heading toward the other side of the city. On its isolated, furthermost edges, where a mountain blocks the encroachment of the forests beyond. When I approach, I see her sitting cross legged there among the rocks as if she were one of them. I see that the sun has tanned and dried out her skin so much that she’s almost the same color as the surrounding rocks. She looks at me but doesn’t recognize me.

She turns her face far away. I hear her humming faint songs of which I understand nothing, except that their rhythm makes me tremble. Her despondent look and pained voice tell me she sings of waiting and loss. Unlike him, she doesn’t need to numb or drug her senses. Her hallucinations are enough; she doesn’t need any outside help.

She stops singing and begins a monologue, in which she says that our friend has become one with water and she with fire, then she asks a question about me, even though she’s unable to recognize that I’m there watching her. I understand her question, but I don’t bother telling her that for my part I’ve joined with wood, but unlike them I won’t merge with my earthly element, I will remain pure mind.

Imitating her cryptic way of speaking, I say, in a voice approaching a scream: “Mind is the divine substance of Atum and it is the light that emanates from a sun invisible to impure eyes, which is why I will become pure mind, wishing to draw closer to Atum.”

It seemed as though I saw a glimmer of understanding in her before that unseen barrier came up to divide us once again. I consider her with pity, I see myself in her, and her in our friend. All three of us different reflections of the same origin. All three of us a dream intertwined in Atum’s mind, an idea that suddenly occurred to him. Just as this deceptive universe occurred to him — in the very beginning — as a stretch of endless water hidden beneath layers of mist, before he slowly established it and furnished it with things and turned its chaos into order.

War is a conspiracy against silence. Its main goal is to kill silence, to fill the gaps with as much noise as possible, as if it were terrified of silence and unable to bear it.

Or at least that’s what she keeps repeating, until I lose my connection to the present and find myself in the heart of an ancient world. She says that I am the arbiter between chaos and order. The mediator between the gods of good and the gods of evil, allowing neither to dominate the other.

It feels like she’s mistaken me for Thoth, the god of writing and wisdom and magic in Ancient Egypt, and then I’m sure of it when she explains her idea that order needs chaos to support and distinguish it, and that good has no meaning in the absence of evil. And I, in accordance with her continuous monologue, am entrusted with the difficult task of maintaining balance between opposites.

In a way, she wasn’t far off from the truth, even though she wasn’t fully able to comprehend my role. I’d tasked myself in fact with something that at that point I’d grown tired of and was no longer motivated to continue. In this place at the edge of the world, I fight to forget, even though my memory remains vital and beating. Sometimes I envy my two companions: he for his ability to absent himself from his own mind, and she for her inherent hallucinations, with which she’s able to cancel out reality, to divide us one from the other, to the point where she can no longer recognize me though I’m almost the sole focus of her monologue, even if she has clothed me in raiment not my own.

I expected her hallucinations to center on what happened before she entered this phase, except she doesn’t remember anything about the constant shelling and bombing and explosions. Or at least she doesn’t seem to when I’m there. Lucky for her, she isn’t like me, haunted by rubble and terrified screaming and corpses tossed in the streets being torn apart by carrion and wild animals. Nor is she haunted by the obsession that every bird or animal on this earth, whether tame or wild, is stuffed full of human flesh. An obsession that repulses me from every kind of meat.

Her memory — it seems — simply expunged itself of everything to do with the last war and the earthquake that followed it. I think about its thundering, its explosions and rumbles, and draw the conclusion that war is a conspiracy against silence. Its main goal is to kill silence, to fill the gaps with as much noise as possible, as if it were terrified of silence and unable to bear it.

Maybe that’s why I became partial to silence, trying to drown myself in it. Gradually replacing speech with writing. I wanted writing to absent sound, but found that it still carried speech inside it. I keep silent until I almost forget the sound of my voice and its tones are erased from my memory. I write down thousands of words a day in a language I invented for myself, in letters I forged to my liking. Only I can penetrate its true depths. I think about carving it into the rocks, or tattooing it on my skin, then content myself with jotting it down on papers I make myself from tree bark, from the distant self that remains hidden from my own eyes, but which constitutes my true essence.

The thought flashes through my mind that a possible reader won’t be able to understand what I’m writing, and might not even be able to decipher it as a kind of language rather than the random scribbles of a confused mind. Contrary to expectations, the thought comforts me. It refreshes me, cools my heart. I decide not to leave the matter to chance, and resolve to destroy my writings myself, one by one. This is why I prefer the fragility and fleetingness of paper to the sturdiness of stone.

What I write scares me, because it confirms all the horrors I’ve seen. It revives and repeats them endlessly, so that they’ll never be erased from my memory. What terrifies me is that when I write what I witnessed I feel that there’s a hidden beauty inside it. Language betrays me, it pulls me toward its splendor. I read and find destruction alluring, daily death reconstructed with a brilliant precision that purifies it and disconnects it from the pain, dispelling it far from the scene, if only temporarily.

I intended to document everything I encountered, to record even the most mundane events, to describe the most minute changes that no one might notice except me. Except I slowed down. I lived it all to its fullest extent. I saw the place reduced to rubble, and the survivors fleeing, one after the other. At the beginning a few remained, wandering the streets aimlessly. My companions learned to ignore them and I myself never remembered them except when I caught a glimpse of one of them staggering around dizzily, making me feel dizzy in turn. Then everyone left except for us. In one way or another, the others disappeared as though they’d never existed in the first place. I remember the empty streets, the destroyed houses, the traces of fire on the public buildings. During those first days the sight was shocking, then I began to get used to it until I barely remembered the previous life of the city, and whenever its memory was extinguished, the devastation would bloom inside of me.

I write, and still write, with the feeling of being the final witness. The person without whom everything will disappear and be swallowed by nothingness. I tell the story of a place reduced to ruin, a silence permeating the entire universe, and the last three people remaining in this city: one adrift in their memories, one numbing his mind and senses continually, and a third whose hallucinations and bouts of madness have pulled her toward a hazy world impossible to identify.

I think about this and it reassures me, then I go back to doubting everything. How can I tell if what I see and believe is correct? How do I know that my vision of reality is the one closest to its truth or essence — if it even has a truth or essence in the first place? It pains me that there’s no way to be sure of anything. My version of the world isn’t better than theirs. It’s more as though we were three separate worlds in one place, three people, each of whom is a prisoner of their own mind, hallucinations and fantasies.