Malu Halasa

A dramatic reappraisal of sex and sexual matters by Syria’s younger generation of activists swept the country following the uprising. Ordinarily before 2011, twenty-something Muslims used euphemisms to vent their frustrations. Derogatory language was not considered polite or acceptable in a traditional society firmly anchored by family and honor. Now social media has provided a platform to air more explicit views. One young Syrian wrote “dick bitch” twenty times on his Facebook Page and then added: “Now do I have your attention? Four-hundred people died in Syria today.”

For some, sex has become one way to deal with the violence around them, according to a 29-year-old woman journalist and activist who asked not to be identified. “A lot of people’s relationships have collapsed and new relationships have begun,” observed Layla (a pseudonym.) “As a generation we used to be obsessed with what people were doing or what they thought. With so many depressed, imprisoned or dead since the beginning of the revolution, it’s understandable that many people are moving to the extreme.”

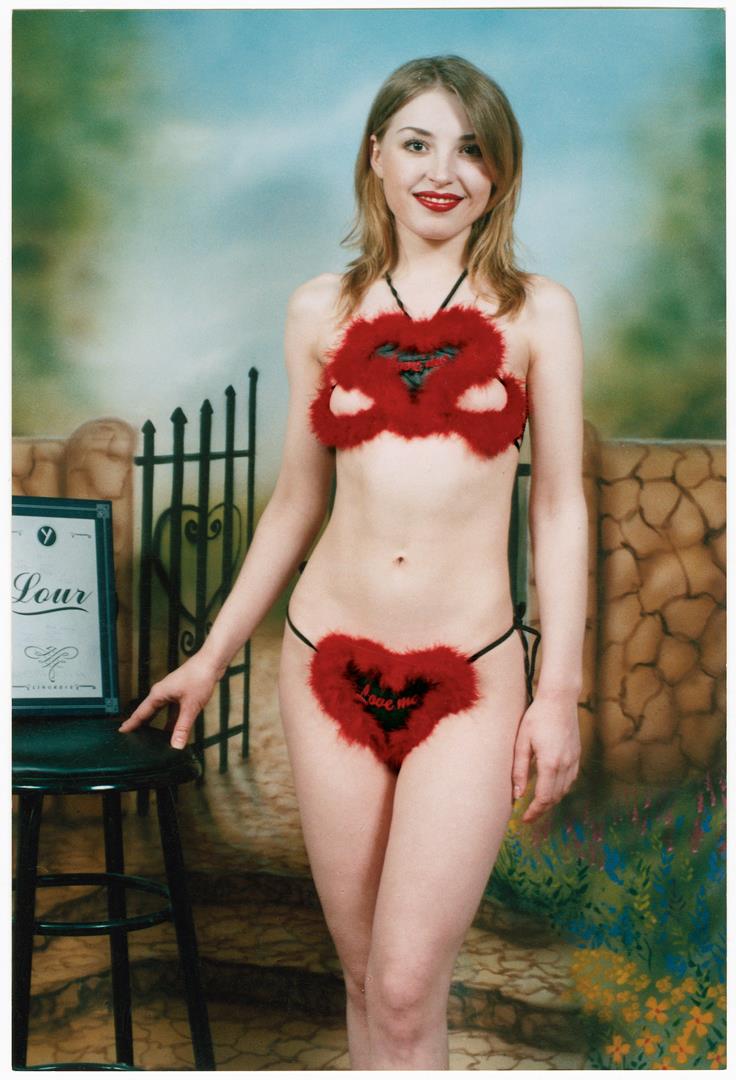

As much as some Syrian activists have been able to express themselves, in the frontline of a political battle, sex has been used to undermine public figures. In 2012 a photograph of a woman posing in skimpy lingerie, with her back to the camera, was included in a cachet of hacked emails allegedly belonging to President Bashar al-Assad. The woman, later identified by activists as presidential aide Hadeel Ali, was responsible for coining Assad’s new nickname bataa (“duck” in Arabic) to great hilarity among Internet pranksters. The authorities too were not above dirty tricks and released an embarrassing private Skype conversation between a free Syrian Army commander and his significant other. Since then, the commander has been discredited and disappeared from view.

As much as some Syrian activists have been able to express themselves, in the frontline of a political battle, sex has been used to undermine public figures. In 2012 a photograph of a woman posing in skimpy lingerie, with her back to the camera, was included in a cachet of hacked emails allegedly belonging to President Bashar al-Assad. The woman, later identified by activists as presidential aide Hadeel Ali, was responsible for coining Assad’s new nickname bataa (“duck” in Arabic) to great hilarity among Internet pranksters. The authorities too were not above dirty tricks and released an embarrassing private Skype conversation between a free Syrian Army commander and his significant other. Since then, the commander has been discredited and disappeared from view.

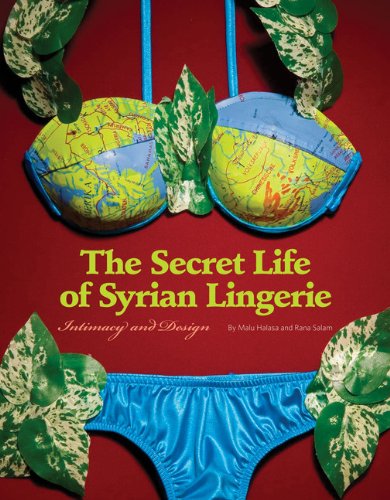

Unknown in the west, Syria has always had a reputation among the countries of the Middle East for raucous sexual humor, which has its origins in the souk. However the humor was one that was rarely expressed in wider, better behaved society. I first encountered it while researching the country’s racy lingerie culture, with the Lebanese artist Rana Salam. Soon we discovered a universe of mobile phone thongs, and panties and bras, which played pop songs, vibrated, lit up or fell apart at the clap of a hand. The time we spent in the lingerie factories, and with the sellers of lingerie in the souks of Damascus and Aleppo became the basis of our book The Secret Life of Syrian Lingerie: Intimacy and Design that was published by Chronicle Books in 2009.

The underwear was shaabi — populist and vulgar. It was a design culture that became an established homegrown fashion industry and underground export success story, which flourished under dictatorship. Here were products designed and manufactured by religious Muslim families for an observant clientele, which in the malls of Saudi Arabia as well as Middle Eastern trinket stores in West London’s Shepherd’s Bush Market.

It is an industry with sinister undertones, as explained by Layla. In her view the lingerie reflected “the habit of a deeply repressive society but one that was sexually oriented and carried on the traditions of Scheherazade’s One Thousand and One Nights. It keeps people absent-minded and later exploits them in a vicious network of tradition, religiosity and authority.”

Dirty Jokes

Equally as lurid as the lingerie’s grab holes, revealing netting and unexplained zippers were the sexual jokes and banter that sometimes took place between Syrian men and women, in closed quarters, at private parties. The Syrian political scientist Ammar Abdulhamid provided an example of a joke. It concerns a ladies group that met for morning coffee once a week and chatted about their lives.

A woman looking unaccountably happy joins her friends, which prompts them to ask her, what’s going on. She tells them: “Yesterday my husband Abu Ali came in from work. As he changed his clothes I stuck my hand between his legs and told him, ‘Abu Ali, your balls are very cold. Can I warm them up?’ It was a night to remember!”

At the next gathering of the women, another in their group also seems content and her friends quiz her. She explains, “When my husband came home from work he was changing his clothes. I stuck my hands between his legs, saying, Abu Antar, your balls are very cold, can I warm them up?’ It was a night to remember!”

On a third occasion, a woman arrives to the coffee morning with a black eye, and a limp, which shocks her friends who cry out, “What happened to you?”

“Well,” she says, “when Abu Muhammad came in from work and changed his clothes, I put my hands on his balls, and said ‘Hey, Abu Mohammed, why are your balls warm, not like the balls of Abu Ali and Abu Antar?’ It was a night to remember!”

The vulgar and misogynistic joke has a violent twist at the end, like much Syrian humor. It echoes a famous cartoon by the country’s premier editorial caricaturist Ali Ferzat. A tortured prisoner hangs in a cell filled with body parts. Sitting on the floor, the man’s jailer watches a soap opera on TV and sobs. Just as Layla suggested, romance and sex are distractions from day-to-day reality of totalitarianism.

Her late father, a prominent political dissident, related an exchange of tragic humor, which he witnessed during his incarceration in Tadmor, a notorious prison located near the famous archaeological site of Palmyra in remote eastern Syria. An inmate had been badly tortured by guards, after a mass demonstration by prisoners had gone badly wrong. Once the beaten man was returned to the prisoners’ hut, the other inmates surrounded him. Everyone felt terrible and guilty except for one prisoner, who pushed his way through the men to the front. He asked the tortured man, “Did they curse your mother’s vagina (kiss imak)?” To which everyone burst out laughing.

Nothing else mattered, Layla shrugged, “rest assured, [the tortured man] could go to heaven. He and his family’s honor were intact.”

Of course, the question remains: Isn’t humor and chatter about sex somehow “too trivial” to indulge in — especially when at the time of writing estimates place 60,000 Syrians dead; 2 million displaced inside the country; and nearly 1 million languishing in refugee camps in Jordan, Iraq, Egypt and Turkey? In the current tragedy as in broken societies elsewhere throughout the years, gallows humor is a typical response to political horror. Sex and humor are subversive ways of reaffirming one’s humanity in the face of oppression. And satire is itself a barbed weapon. Mockery and derision are the last things the Baathist regime seems able to cope with. After cartoonist Ferzat breached what he described as “the barrier of fear” and started drawing satirical caricatures of Bashar Assad – something he had never done for the current president or the previous one — he was attacked by pro-regime thugs in 2011. They told him, “Bashar’s boot is better than you,” and broke his hands. Ferzat, who has since healed, lives in exile in Kuwait and has started drawing again.

Sex and the Single Muslim

The novel The Silence and the Roar by Nihad Sirees, translated into English by Max Weiss, explores the intertwining of humor, sex and violent intimidation that is Syrian. Originally published as Al Samt Wal Sakhab in 2004, it tells of a day in the life of Fathi, a banned writer who survives censorship and threats by laughing and having sex. Sirees, a writer from Aleppo better known in for his historical television series “The Silk Road,” did not succumb to the feel-good factor that permeated the early years of Bashar Assad‘s presidency. He too had been one of the country’s intellectuals who had high hopes for change during the short-lived 2000 Damascus Spring. When out-spoken critics and petition signers were imprisoned, Sirees withdrew, watched and waited. The Silence and the Roar is the fruit of his frustrations. The novel is set against a hysterical daylong mass march, during which crowds proclaim love for the “great leader” under the menacing eye of the secret police operating in an unnamed country.

The tense fragmenting of the family — the one institution, which should provide a safe haven from an intrusive state — is at the heart of the story. Fathi’s 56-year-old widowed mother spends her time on her bed, and watches the march on TV, as she preens herself for an upcoming marriage to a regime official, who has in his sights his wife-to-be’s son. Meanwhile Fathi, disturbed by the roar of the crowd, seeks solace and silence in his girlfriend’s bed. In the west, sex is often seen a private, consenting act between individuals. In a country where people are pawns by the state, Sirees believes an active unfettered sex life can be an expression of freedom and a very public stance against repression.

At the beginning of the Syrian revolution in 2011, there was a little-known offshoot to the struggle that no one acknowledged in public. Syrian artist Khalil Younes, originally from Damascus, called it “shy trials,” or experimentation with changing sexual attitudes.

As a fully fledged war engulfed the country, he said more young Syrians are revealing their private lives in detail: Who they’re looking for, what they want and how they feel on their Facebook page status updates. It has become a trend among the young because they are encountering so many Syrians like themselves engaging in candid self-reflection. This is led to more open attitudes towards sex.

With levels of violence rising across the country, it is understandable that people retreat into their bedrooms. Another 28-year-old activist believed there has been a marked sea change among people in his generation towards having. As we discussed, the waves of children born in the Dheisheh Palestinian refugee camp in the occupied West Bank — the product of months-long lockdowns and no electricity from Israel in the 1990s – he suddenly cried out, “This is exactly what’s happening in Syria today.”

However, Layla wasn’t convinced that a Syrian sexual revolution was in full bloom. Too many people, she’s stressed, have fled the country and some of those who remain at home have gravitated towards what they know best – conservatism and religion.

A New Business Model for Islam

Sex and humor are not new in the Arab world. In the ninth century, raconteur and theologian Al-Jahiz was making penis jokes in Baghdad. His most famous quip about the Al Quraysh tribe of the prophet Muhammad would make the most ardent Salafi blush today. Salwa Gaspard of Saqi Books of London and Beirut observed that even though a sanitized version of One Thousand and One Nights was told to them as children in Lebanon, the humor and sexual innuendo of the East’s most famous folktale were not completely lost because kids “could imagine what was going on.” Today, there is a crisis in Arab publishing. The only books published in their thousands and selling like hot cakes in the region’s book fairs, where the Arab world obtains most of its reading material, aren’t the classics but Islamic religious books.

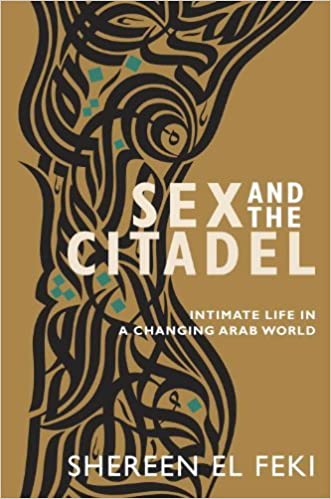

“When the Arabs were confident they talked and wrote a lot about sex. Once our culture declined and the people became less self-assured, sex was not discussed in public,” observed Dr. Shereen El Feki, UN Commissioner on HIV and the Law. She explored medieval Islamic sexual manuals and encyclopedias in her impressively researched book, Sex and the Citadel: Intimate Life in a Changing Arab World.

Abdulhamid, a former religious fundamentalist, changed his mind about extremism. He wrote a novel entitled Menstruation, and recalled the evening sex education courses at his local mosque, during which women’s bodies; their fluids and cycles were much discussed and analyze. This and the continuing popularity of Abdelwahab Boudiba’s Sexuality in Islam, first published in 1975, surely must counter the prevailing western misconception that Islam is somehow prudish.

In the Syrian souk, sexual punning was on display in the form of jokey, fun underwear on the lingerie stalls or behind the glass plate glass windows of women’s clothing shops. In photo albums, which showed off different styles of lingerie available for sale in the shops, Eastern European women modeled bits of Lycra and feathers — not in a sexualized manner as seen in the advertising of Victoria Secret or Calvin Klein, but in snaps by local photographers, which feature nipples, crotches and big encouraging smiles.

Now the lingerie companies are not selling the volume they did when Gulf Arabs in the niqabs flocked to their wholesale showrooms and factories. Still, during the uprising, the lingerie trade flourishes. As bookseller Stephen J. Gertz wrote in his Booktryst wrote, despite increasing danger in Syria’s capital city it was “revealing that the purveyors of lingerie in Damascus’ souk Al Hamidiyah business is good if not brisk.” In a BBC report, a camera panned along the souk’s stores and stalls, to show torso mannequins outfitted in colorful lingerie outfits.

The justification that the lingerie served a much-needed purpose — to break the ice — in traditional, arranged Muslim marriages between the sexually inexperienced on their wedding night — will no doubt pacify the Islamic fighters of Al Nustra Front — if and when they finally reach Souk al-Hamidiyah. Not even they will be able to stand in the way of the lingerie proprietors. The stalwart Sunni religious families are exactly the kind of savvy Muslim businessmen whom the Syrian intellectual Sadik Al-Azm maintained will be at the forefront of a moderate and commerce-minded Islam poised to take over the country once the violence ends.

The Syrians, known in the Arab world as “the Chinese of the Middle East,” have always found a way to make a profit even when on low reserves of foreign currency, which stopped them from bringing machines that made nylon thread across the border. At the height of the Hafez Assad dictatorship, a cotton lingerie manufacturer told me that he and the other factories in Aleppo sold literally tons of ill-fitting underwear and tee-shirts to the Soviet Union — perhaps one reason for Putin’s disdain of Syrian aspirations for freedom. A new phrase has been coined for a more tolerant interpretation of Islam born out of the experience of countries in the Levant, which allegedly respect citizenship and individual minority rights while placing a healthy emphasis on business. Its name “Shami Islam” borrowed from the classical Arabic for Syria “Sham,” which later came to represent Damascus, a city known for an ancient mercantile past.

The capital’s sexy lingerie industry was never considered tanfees. In The Ambiguities of Domination: Politics, Rhetoric and Symbols in Contemporary Syria, University of Chicago professor Lisa Wedeen identified Syrian cultural production — from movies to TV-mini series, even Ali Ferzat cartoons — as vehicles to vent anti-regime views. While it is in the nature of tanfees, to let off steam in a pressurized, heavily controlled society, and this negates the need to bring about real change in Syria that will stop the imprisonment and torture of political activists and dissidents. It will be incumbent on crime tribunals to do that.

Between the political elite — both dissident and pro-regime — on one side and the vibrant and sometimes course Arab Street, on the other, there has always been an immense disconnect. This gap due in part to class and education was also widened because of language. Middle Easterners of substance and distinction in Syrian society were expected to write and express themselves in “proper” Arabic. The revolution that will probably outlast all those that began in 2011 is the one presently taking place in communications and social media. Under the pressure of the on-going conflict, young Syrians have adopted a more direct, sometimes crude, language on Facebook and Instagram to convey their frustrations, hopes and desires. For them, sex, humor, and straight talking have become the tanfees of the Syrian uprising, and where that will lead them and their country only time will tell.

This essay original appeared in print under the title “No Sex Please We’re Syrian: Confessions from the Lingerie Drawer” in Fetishism in Fashion by Lidewij Edelkoort and edited by Philip Fimmano (Amsterdam: Frame Publishers) 2013. The essay was written on the occasion of “Sex and Humor as a Response to Syrian Dictatorship, Violence and Oppression,” a panel with Nihad Sirees, Galia Kabbani and Malu Halasa, chaired by Rosie Goldsmith and supported by English PEN, at Waterstone’s Piccadilly London, January 30, 2013.