…I was longing, reminiscing, ruminating, over the ubiquity of absences in our daily lives. I wanted to trace oral histories in a concrete way, yet no longer see history as a chronological timeline. I now see it as expanding circles of lifetimes. Our relationship to the places we inhabit is the same. Home is a place that does not have a start, middle, or ending. It just is.

Yesmine Abida

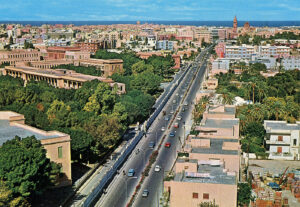

For the longest time I walked through the narrow blind alleys of Nabeul’s medina, the old town, unaware of the Jewish community that once roamed its streets. It was not until the summer of 2021, in my grandparents’ bedroom, almost pitch black except for the lights peeking through the window blinds, that my grandfather informed me of his experiences interacting with Nabeul’s Jewish community. I sat on the side of his bed, hearing stories of people I’d never met. My grandmother often interjected, recalling Josephine, a beautiful Jewish nurse with blue eyes, who helped her nurse my uncle, their oldest son, when he was a newborn. This helped solidify a bygone world in my mind, given that, to me, the Jewish community of Nabeul was close to an enigma: shadows of history that roamed the same places as I do, not leaving a trace of their existence behind for me to retrieve. I became aware that I was part of a larger collective forgetfulness, among the generation of people that moved to Nabeul as a result of urban growth. As Jews departed the city between 1948 and the 1980s, many Muslims relocated to it, in part for its pleasant breeze, pottery, and harissa. Muslims moved into the houses vacated by Jewish families, and emblems of an interfaith past gradually faded away. Ceramic stars of David scattered across walls were lost. Dust accumulated in synagogues, and Jewish-owned businesses were sold or passed to Muslim apprentices or business partners.

I returned to Nabeul the following winter. The blue-colored bedsheet on my grandparents’ bed was replaced by thick beige duvets. The television that stood to the left of the bed was replaced by a photograph of my grandparents taken a few years after they were married, and a Quran. I searched for my grandfather in the living room, since the television was turned on, but nobody was there. The room, long emblematic of his obsession with the news, was empty, but still somewhat inhabited by his presence. I visited my grandfather’s grave that same day. The fig seeds that my family planted in October had started to yield leaves. In Muslim North African cemeteries, it is common to plant vegetation on top of marbled tombs. The leaves and flowers are reminders of how long since the departed are no longer among the living. I sat on the marble bench next to his grave.

“Do you like his grave?” my aunt asked.

I nodded.

We fed the pigeons of the cemetery corn kernels. According to my sister, the day my grandfather was buried in the cemetery, birds flocked to his grave, following my family. I want to believe that they were paying their respects to my grandfather. He was an avid bird-owner, and had had about 50 under his care. My grandfather’s connection to birds reminded me of another story that I heard during my research on Nabeul’s Jews.

“It’s my mosque” was one of the first pieces of information that Désirée Haddad shared during our first virtual interview. She was born in 1943, into a bourgeois Jewish family in Nabeul that traces its origins to the Tunisian island of Djerba, and before that to Palestine. She grew up in a three-story traditional Arab house, nestled deep in Nabeul’s medina, right next to the Grand Mosque. The house’s open ceiling gave the impression that the mosque was inside the house, and throughout the day, the adhan and five daily prayers echoed throughout the premises. The mosque was a part of her daily life, and more than anything else, part of her family history. Before her birth, in 1919, her mother was summoned to Nabeul’s municipality; the object of that summoning was the two boutiques, owned by Haddad’s mother, located next to the mosque. The municipality wanted to buy the two stores, which were no longer in operation, and Haddad’s mother asked what they would become, to which the municipality representative responded that they wished to expand the mosque. Haddad’s mother donated the two stores without taking a single dinar or franc in compensation. On Fridays, she made couscous and served it to Muslims leaving Nabeul’s Grand Mosque after Friday prayer. She also relayed the following story to me:

I promise you, on my children’s lives, that the story I am about to share with you is true. You can include it in your project if you would like. There is a common saying, which will make sense in a minute, that is ‘the sand that covered my mother will cover me.’ My mother was buried in Jerusalem, right in front of Masjid al Aqsa. That was my mother’s dying wish, since my grandmother was also buried in Jerusalem — my family dates its lineage from Palestine. If you stand in front of her grave, you can see the dome of the mosque in front of you, the wall of lamentation to the right and the church to the left. Her epitaph is the only one in the graveyard that says, ‘Born in Nabeul.’ I promise you that every time someone goes to visit her, be it my cousins, grandchildren or anyone paying their respects, the adhan is recited [in Jerusalem]. Just like the adhan we heard on a daily basis in our house in Nabeul.

As I believe stories of an attachment to a homeland after one’s departure from the living, goosebumps ran across my arms. I couldn’t help but create a parallel between the birds that flocked to my grandfather’s grave in Nabeul and the adhan that can be heard in Jerusalem. I wanted to think of home as a place that could feel our absence. That despite absence, a place that was inhabited will always be haunted by those who showed love to it. That the love across distances and lifetimes is only a millisecond-long run.

The cemetery right next to where my grandfather was buried is the Jewish cemetery of Nabeul. The proximity between both cemeteries was often pointed out to me as a reminder of the links of friendship that existed between Muslims and Jews, as there was no hara or ghetto in Nabeul. Members of both religions lived in the same areas, attended the same schools, and their religious buildings, such as the Grand Mosque of Nabeul and the Grand Synagogue of Nabeul, are across the street from each other.

In an usually dry and arid winter in 1936, food prices were soaring. Muslims headed to mosques, prayed and made dua, yielding nothing more than a few clouds on a clear sky. Nabeul’s Muslim leadership approached Rabbi Nathan for his help, asking if the Jewish community could also contribute in prayer. The Jewish community acquiesced to the request, headed to the cemetery, and prayed at the great Rabbi Yacoub Slama’s mausoleum. In due time, rain started falling, and as Jews returned to their houses, Muslim residents exclaimed “Allah is with the Jews,” overjoyed by the much-needed rain. Recalled by some as a parade-like spectacle, the miracle showed its long-term effects the following morning. The rabbi’s wife tried to wake him from his slumber, only to find that he had passed. The belief among all of Nabeul’s residents is that he offered his life in exchange for rain, taking on his shoulders the responsibility of the entire town.

Similarly to the Muslim North African graves, vegetation around Nabeul’s Jewish cemetery highlights a similar passage of time. Wild weeds growing between cracked marble tombstones relate to a different set of experiences, one nothing short of decay. Jewish cemeteries are not safe from looting and destruction of tombs, as these instances have been documented in different parts of the Arab world. Even the dead don’t rest. In Nabeul, Madame Radhia and her family maintain the Jewish cemetery, ensuring that Rabbi Slama’s mausoleum and the graves of Jewish Nabeulis are kept clean, and they guard against looting.

I visited the site during a ziyara last August, where spreads of harissa, Tunisian desserts, and other artisanal objects were on sale. As visitors filled up the mausoleum, they lit candles on the tombstone of Rabbi Slama, posited dinar bills in a basket alongside boukha bottles that would be drunk per Jewish tradition. The rabbi that came from Tunis sat quietly, until he stood, and his voice reciting prayer instantly resonated throughout the room. I observed this moment, and reflected on the implications that come with a return to the homeland. Jewish departure from Nabeul is a segment of the city’s history that has yet to be fully formulated. It is highly politicized, yet understudied. When mentioning my research, some residents would ask me if I was looking for trouble, or what my ulterior motive was. I wasn’t as interested in history as much as I was in the sociology of return. How does one return to one’s place of birth, despite its being unrecognizable from what it once was? A place that has few to no traces of your existence?

Nostalgia has a say in Jewish return, to Nabeul, Tunisia, and to North Africa more broadly. Spatial memory was a significant theme throughout my research on the oral history of Nabeul’s Jews, as landmarks such as the synagogue, mosque, as well as particular alleys of the medina or the city’s corniche were all sites of both interfaith and Jewish life. Yet my first time looking for Jewish emblems in Nabeul’s medina was a challenge. I had to ask several people for directions. On the agenda was to find the Gaston Karila yeshiva, built in 1918 to honor a member of the Karila family who had died due to the Spanish flu. A century later, Albert Chiche (b.1949), the last Jewish resident in Nabeul, who dedicates his time to conservation of the Jewish patrimony in Nabeul, was crowdsourcing on Facebook to renovate and restore the yeshiva, or orthodox seminary, into a small museum. The yeshiva was abandoned for decades, its ceiling was close to collapse, but Chiche’s project in repurposing the site gave it a new life.

In August 2022, the space for Judeo-Nabeuli memory was inaugurated, and its walls were evocative of my Facebook wall, which was full of posts from Facebook groups dedicated to remembering interfaith life. I’d already seen some photos of the leaders of Nabeul’s Jewish community adorning the walls. A large inscription reads “The Last Great Jews,” with a series of descriptions under each photograph. The last hotel manager. The last tailor. The last kosher butcher. The last jeweler. The last barber. The last entrepreneur.

It is difficult to grasp the concept of the last. It signifies not only the end of a community, of lifetimes shared, but of an entire history. The vision behind creating a Jewish museum is informed by Chiche’s understanding of the future. “It would be a shame if it [Jewish history in Nabeul] falls into oblivion… We want people to know we existed here 20 or 30 years from now.” In the museum one finds a chair formerly used for circumcisions, Torah scrolls, family trees, and photographs in two small rooms — a project in heritage and historical preservation of a community that no longer exists as a cohesive unit is much more than what it is. It is a way of rewriting oneself inside of history, preserving a past homeland, and experiencing it once again.

The implications of a return to the homeland is much greater than re-enacting traditions, or recalling stories on online forums from Paris, Los Angeles, or Jerusalem. I looked for counter stories to peaceful interfaith life, and the search yielded very few results. Nabeul was remembered as a place where Jews and Muslims coexisted, and where differences were not so much drawn along religious lines. I turned to studying nostalgia. Nostalgia is the main reason for Jewish return, and for efforts of preservation, because if there is no nostalgia, there would be no engagement with Nabeul as a homeland. Even if nostalgia is often seen as an ailment, a set of delusions that imprisons people in the past, it preserves the places as one once knew them. It explains the set of complicated and contradictory experiences that Nabeul’s Jews experienced in Tunisia following its independence in 1956.

I was in Nabeul, and Monique Hayoun (b.1957) was in Paris, when we had our first virtual interview together. She asked me where I was in the world, followed by saha ‘alik — lucky you. The following hour was full of surprises. In 1974, she was the only Jewish Nabeuli in her Tunisian state school. Hayoun took Islamic class up until high school because she enjoyed it, until a problematic shaykh was hired and made inflammatory comments about the Jewish community. She spent a lot of her time studying with Muslim friends in the library inside of the Grand Mosque of Nabeul. She also revealed the significance of the bakery, Kouchat Ennour, owned by the late Kassem El Behi, who adorned it with Quranic verses and often partook in Jewish traditions. Come the end of Passover, members of the Jewish community would give the remainder of their matza, or unleavened bread, in exchange for fresh bread, which El Behi gifted to join the festivities. Hayoun created the first website dedicated to Nabeuli heritage and culture, nabeul.net, in 2002; it has since become an organization that promotes the economic growth of Nabeul’s larger governorate.

I asked Hayoun the reason for her departure from the city in 1976, and she told me that she left to pursue her university education in Paris. It was usually the case that families left together, so the Hayouns left as a unit, and the community, which numbered 180 in 1976, shrank by seven people. Departure and exodus are usually discussed as a cumulative process. Jews leave, then more leave, and then even more leave. Fewer synagogues are fully operational, and there are fewer Hebrew schools, fewer Jewish-owned businesses, fewer kosher butchers. In the 1970s, Hayoun’s grandfather led synagogue services, despite not having received proper rabbinic training. The end of her time living in Nabeul as a full-time resident was shaped by various deficits. But she didn’t discuss it that way. Before the end of our conversation, she sent me the link to a video on Facebook entitled “Nabeul Mon Amour,” a project by a film student in Nabeul, in which Hayoun discusses her upbringing in Nabeul and how she started nabeul.net. Her words sparkled, and her palpable love of Nabeul shone through her recollection of its people, streets, scents and flavors. It was as if she had never left.

“Tell your grandmother I say hello.”

“Will do. Thank you for taking the time to talk to me,” I replied.

I closed my laptop and reentered my grandparents’ bedroom. The link between nostalgia and space became much clearer to me. I was grappling with the experience of being home, well aware of my grandfather’s absence. As a parallel, I was walking around the medina following my virtual interviews, cognizant of entire lifetimes and experiences, once shared in Judeo-Nabeul but now absent. I saw a lot of boarded-up houses, knowing that half of them were locked as a result of disagreements over inheritance, with the other half houses of Jewish families that were never sold but were in some instances seized by the city municipality. I was frustrated, unsure whom I could fully blame for this loss of home. I was also frustrated by how little is known about Nabeul’s Jews and by the fact that up until the last few years, during which interest in religious minorities in Tunisia has increased, little research or documentation has been done by residents of the city. At heart, I was frustrated by how home is a place. A place that is difficult to describe, as it moves forward and waits for no one. A home is a place that is built, rebuilt, and with the passage of time, subject to decay. “Home is a place” repeats in my mind as a prayer does. Home is a place that I want to preserve but might not fully be able to.

“Mama Rachida, Monique says hello!”

“Who?” my grandmother replies.

“The lady I just interviewed.”

I stood next to the stove as she prepared dinner for both of us.

“Where is she now?”

“She’s in Paris.”

“How nice is that, a native Nabeuli in Paris whom I have never met sends her hello to me? Bless her.”

I still have hope. Hope in the stories of young Muslim and Jewish teenagers coming and going between houses, sharing plates of mloukhiya or lighting the stove for neighbors observing shabbat. Hope in the fact that Theodore Chiche’s sandwiches are still remembered half a century later as the best in the city. Facebook forums dedicated to sharing memories of the past have solidified my sense of hope. Together, they have become a new type of homeland where, following diaspora and exile, Jewish and Muslim Nabeulis maintain a feeling of community in the digital realm, and create their own homespun archives. I joined these Facebook forums to find people to interview about their earlier lives in Nabeul, and both my heart and field notes were full, yet I was still longing, reminiscing, ruminating, over the ubiquity of absences in our daily lives.

I wanted to trace oral histories in a concrete way, yet no longer see history as a chronological timeline. I now see it as expanding circles of lifetimes. Our relationship to the places we inhabit is the same. Home is a place that does not have a start, middle, or ending. It just is.