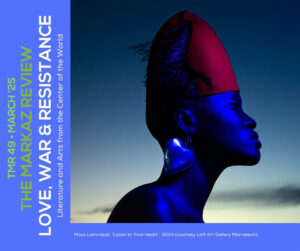

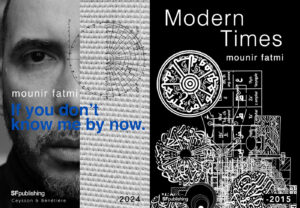

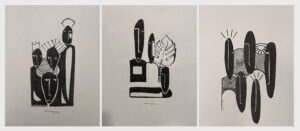

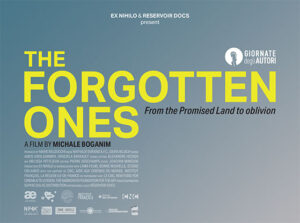

The Moroccan artist Mounir Fatmi’s work is now showing in Europe and the Gulf through early next year, as part of the global exhibition of art from a pre and post-internet age, The Silent Age of Singularity, at the Prince Faisal Bin Fayd Arts Hall in Riyadh (through 27 February 2025) and in his solo exhibition, If You Don’t Know Me By Now at the Ceysson & Bénétière Gallery in Lyon in France (till January 18, 2025). Sophie Kazan Makhlouf met the artist to ask him about his studio practice, why he makes art, what he thinks of global audiences, and why he likes to hear audiences react to his work.

Hello Mounir. You have described art as “un piège esthétique” (an aesthetic trap). Can you tell me a little more about what you mean by this and how you see the role of the artist setting these traps?

I have always believed that artworks can have a political or religious or societal meaning but before all else, a work of art must be aesthetically pleasing. That is what the artist uses to … attract an audience to their work and allows for communication. So in that sense [I see] the audience falls into the trap — if they don’t fall into the trap of that particular artwork, they will never take the time to reach the various levels of understanding and meanings that the artist has created. I have thought and worked a lot and attach a lot of importance to that first aesthetic visual dialogue that the artist creates. That is why I call it a trap — you just have to look at a work by an artist like Jackson Pollock … they [the artist is] causing a reaction in the viewer. As you look at a work of art, you fall into the trap or under the spell of that work. It’s takes us into the work — looking at a Pollock, you don’t see the drips of paint and just stop. You see that there is a lot happening aesthetically and after that, you try to understand the work and the intentions of the artist. For me, all works of art are this kind of an aesthetic trap.

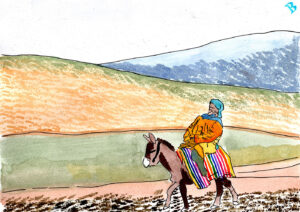

Since I left Morocco, I have been thinking about the role of the artist and particularly: What is the role of the artist in a society in crisis? When I first got to France, I was asked what interested me and that is what I said. I also asked myself how an artist is supposed to be creative in a state of crisis? Lots of critics asked me what crisis I was talking about. They didn’t see the crises that were happening in smaller, poorer countries in the world. In 2011, the Arab Spring affected the whole world and then came the fall of dictatorships — we have just witnessed the situation in Syria. In Europe, there didn’t seem to be a crisis and so people didn’t see what I was talking about. All they could see was the migrant crisis of people coming from other places in the world and so it seemed like their problem. The two realities didn’t seem to connect!

As an artist, I asked myself how I could be creative in a world in crisis…What does it mean when there are people in such need and without food? So I realized that making art became a provocation in itself!

How does this notion of crisis sit with the idea of the artist setting traps to attract viewers?

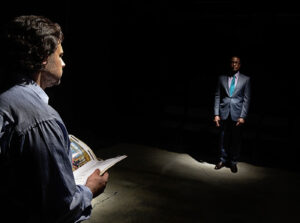

The notion of crisis is a first step, like a questioning of the role or need for a work of art. For example, The White Matter (2020-2021) [a film installation currently showing in The Silent Age of Singularity in Riyadh] is about failure. The juggler in the film can’t juggle with books. When I was making the film, I asked a professional juggler who had trained at a professional circus school for help. He said that he could juggle everything and anything! When he arrived in the forest, on the set, I gave him books and told him that’s what you’re juggling with. He said, no I can’t. I asked why not? He said that he needed objects with the same shape and weight. He got annoyed and cut himself trying to juggle with the books. You see, juggling is mathematical and habitual. We did a lot of takes and at the end I told him not to worry … in fact [his dropping the books] is what I wanted. I wanted failure… that is how humans gain experience and learn. It’s all learned and linked from failure. It isn’t the aesthetic of crisis, but crisis has always pushed me to question the world and push the boundaries. Faced with failure, is when one can get philosophical and creative!

Thinking about the way, The Silent Age of Singularity exhibition focuses on a post-internet era and remembering the juggler dropping the books. You could have manipulated an image with AI nowadays to solve the problem, using technology. Looking ahead, how do you see the role of the artist and also aesthetics changing and developing with technology as a tool?

That is a question that I am often thinking about in my work. Technology and the transmission of knowledge — because technology links to religious thought too! Re-linking things and the cables I use for so many things, most recently for my work from 2018 that is currently in the exhibition [at Ceysson & Bénetière in Lyon]. Cables are wound and bound and link things almost like a measuring tape, giving information and binding things together.

I saw how my father in our childhood home in Tangiers was suddenly empowered when he brought in a new television with all the wires and electric cables to install it. I was fascinated by the cable.. first it was probably the only sculpture that we had outside our house [laughs]! I saw the change in my father’s behavior — the television and the cables gave him power; he was in charge of it, switching it on and off, it was like his second wife! He was master of the television and this power over technology .. it’s quite a masculine power. Whether it is the typewriter — you can read in Levi Strauss’ Question of Power about the function and the subject of power. Texts for men and textiles for women maybe [giggles]? I’ve done lots of work using prayer carpets — textiles are all linked and linked to religion and media… Of course, these are not at all sacred or religious carpets for prayers — they’re made in China or Turkey. It’s interesting, too, to think of mediums as mediators between two states of being, or cultures and between different ideas…The cable that transmits and technology.

I have been looking at this a lot and also obsolete forms of technology. At the recent exhibition in Lyon, young people came up to me and asked what the cables were for? They don’t see them used anymore! Televisions are networked now [wireless] and they watch television on their phones too… It’s almost like archaeology — archives for future generations!

You have described how you see the artist working in crisis and the aesthetics traps laid for viewers. With technologies changing and materials changing. How does the viewer fit in to this equation?

The viewer remains at the center of the artist’s sights. When I speak about traps, this is the way that the artist finds their spectator. The magnificent moment is when the artist sees a spectator looking and considering their work. That’s an incredible feeling — when they see someone looking at a work that has come from you. It must be the same feeling that a writer gets from someone reading their book — you have a connection, a direct connection with that person. The viewer is always central and works such as The Fire Circle (2017) which is also part of The Silent Age of Singularity exhibition in Riyadh relies on audience participation or interaction to “work.” It’s not a desk so the viewer enters into a game where they know that the cable works and transcribes. I got letters from people who got carried away in the immersive installation. I received 500-700 word pieces of prose, or poetry. The spectator is at the center of things for me … otherwise, there would be no reason, no way.. I wouldn’t want to make art just for me!

Do you feel the public needs this communication with the artist?

I agree. It’s about give and take. When the artist shows a work, they need a return or a reaction. With social media it’s not like the experience of everyday life. When you’ve written something or made something hopefully you get a reaction or review from the press or critics. Bad reviews are really bad reviews when they don’t give an opinion or a reaction. It’s about getting a reaction that it counts! There used to be a “golden book” in galleries or at fairs, where members of the public would write their thoughts and opinions. That was wonderful.

A question about reactions — I know that you regularly show work in the Arab world, in the Gulf as well as in the far East and in Europe. How do you feel art publics differ and art critics are more or less vocal in different parts of the world? As an artist, what has been your experience in exhibitions around the world?

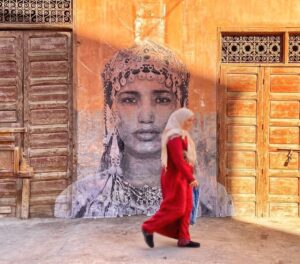

I think that the Arab public has changed a lot since the Arab spring. There is before and after. I think the Arab Spring caused a political and an artistic liberation for people. There is a much wider acceptance now of media like photography and video and a younger public has stepped in. Unlike my older generation, they are more at home with images and image creation. The younger generation [in the Arab world] is also more technologically aware and have caught up quickly with other networks. It is as if the world had lost its center and has become a network that no longer needs a center.

Exhibiting in Dubai, at Riyadh, in Casablanca, Tangiers, in Paris or Tokyo is the same! The publics in those cities have all seen the latest films, they know the latest songs… they speak the same language of images and social networks. A Japanese public is therefore not very different to any other as a result.

There is more dialogue and of course more acceptance of new technologies. In the future, we can expect an even more integrated style of working [with the public and through technology]. Members of the public are becoming increasingly involved in art. That is where things seem to be heading; to a moment where the public doesn’t need to think and just take part in an exchange of interest.

As artists, we are therefore looking to disrupt that kind of exchange and add art and visuals to it. My studio Instagram is extremely active! It’s all visual and focused on communication too. For example, we are doing catalogues in Arabic, in Japanese and in Chinese, it’s all about communication and the big picture… I love hearing collectors who tell me that my work has allowed then to communicate with other generations. They understand that objects are not sacred or religious they are just means of communication!

I’ve seen a huge change since the Arab Spring — a liberation and a new image of the Arab world. [I have also seen] … a hunger for new images and new ideas that go beyond national ideas. With time, the viewer will certainly keep changing — they will become more active and more reactive!