A former political convict in an Israeli prison managed to write a novel and get it out into the world.

The Trinity of Fundamentals, a novel by Wisam Rafeedie

Translated by Muhammad Tutunji and the Palestinian Youth Movement

1804 Books 2023

ISBN 9798988260219

In his introduction to the English translation of his novel The Trinity of Fundamentals, Wisam Rafeedie quotes Ghassan Kanafani’s famous statement in his 1969 novella Returning to Haifa: “[I]n the final analysis, man is a cause.” With this citation, Rafeedie inserts himself into a long tradition of revolutionary fiction. Arguably born in 19th century Russian novels such as Nikolai Chernyshevsky’s What Is to be Done? (1863) and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Possessed (1871-1872), the tradition received a new life in Arabic literature, such as Syrian writer Hanna Mina’s The Snow Comes from the Window (1969). Revolutionary fiction is defined by its aims and preoccupations: how to overturn the existing order of contemporary society. Not all revolutionary fiction actively advocates revolution — Dostoevsky’s brutal critique of revolutionary hypocrisy is a case in point — but Palestinian revolutionary fiction certainly does.

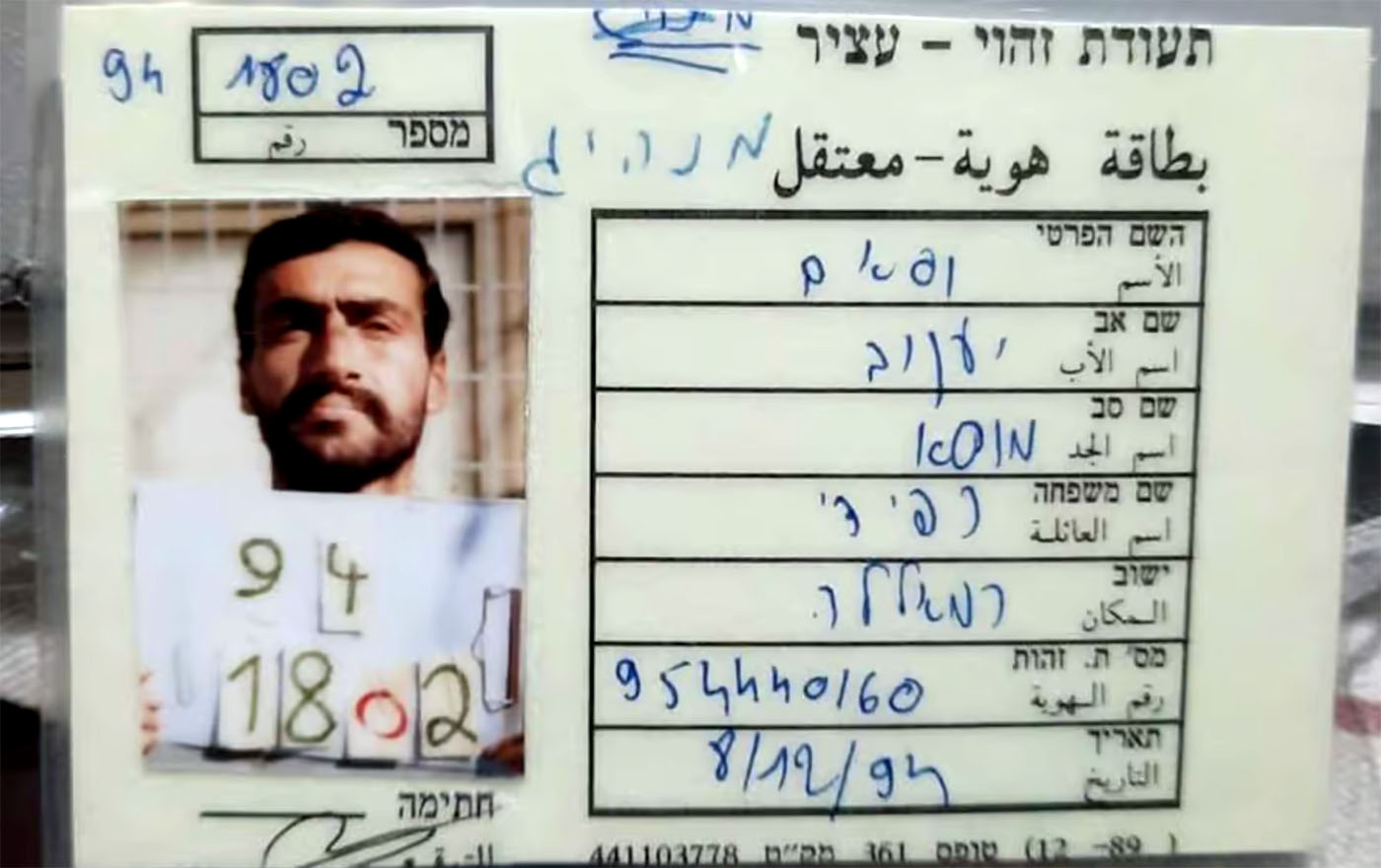

The existence of The Trinity of Fundamentals is a miracle in itself. The novel was composed between 1993 and 1995, during Rafeedie’s incarceration in the Negev desert’s Ktzi’ot Prison (known to many Palestinians as Naqab-Ansar 3), while he was dreaming of being released. In order to conceal the manuscript-in-progress from prison guards, Rafeedie’s fellow prisoners copied sections from the novel in miniature handwriting and stuffed these extracts into pill capsules which they then smuggled to other prisons. The novel was finally published in Arabic in Damascus in 1998. It now reaches the English-speaking world courtesy of 1804 Books and the Palestinian Youth Movement, with Muhammad Tutunji having produced an initial draft. The translation reads well even though it departs in places from the original Arabic.

Even as the manuscript circulated clandestinely from one prison cell to another, Rafeedie languished in his own cell, believing that it had been lost forever. This was because, just as he was nearing completion of the narrative, a prison guard caught onto the prisoners’ methods for smuggling the manuscript and confiscated it. Unbeknownst to both Rafeedie and the Israeli prison guard, the manuscript existed in a second copy. Three of Rafeedie’s fellow inmates had copied the novel onto paper small enough to fit inside medicine capsules, which were then smuggled through six prisons until the author discovered in 1996 that the manuscript he thought lost was being widely read by Palestinian prisoners.

The revolution that the novel’s protagonist, Kan’an Subhi, lives and is prepared to die for is that of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a militant organization to which Kanafani belonged, and which Rafeedie joined at the age of 16. The novel tracks the nine years, 1982-1991, during which Kan’an lives a secret life in the Occupied West Bank, moving from house to house to keep one step ahead of the Israeli military authorities, who have proscribed the PFLP. Kan’an’s family advises him to emerge from underground, so that after serving his time he can eventually lead a normal life, but he has received instructions from the PFLP not to turn himself in and he will not break with party discipline. Kan’an’s uncompromising revolutionary commitments determine the novel’s overall structure. Yet his political principles co-exist with a vast swathe of life, ranging from passionate love to intense pain. Indeed, the title — a more literal translation from the Arabic Al-Aqanim Al-Thalatha would be The Three Hypostases — refers to the three principles which Rafeedie takes to be constitutive of the meaning of everything: life, revolution, love. Kan’an’s task, which he fails to fulfill by the novel’s end, is to unite these three principles into a whole.

Whereas most prison literature focuses on the experience of incarceration, The Trinity of Fundamentals is a novel about life outside prison, written from within a prison cell. The story is narrated in the third person but filtered through the perspective of Kan’an. The story of Kan’an’s underground existence is interspersed with illuminating historical digressions that significantly enrich the narrative and provide insight into the conditions of Palestinian resistance throughout the 1980s. In between explanations of the role of the PFLP in shaping student activism, we read of Kan’an’s love for fellow student Muna and the tensions that his revolutionary commitments bring to their relationship. Muna is looking for happiness, not revolutionary action. She is portrayed in somewhat one-dimensional terms, as a woman for whom “resistance activity only had a superficial influence, like lipstick.” As she fades from his life, Muna becomes a dim memory for Kan’an, and is transformed into the “shrapnel of an image.”

Other women, such as Hind, his last love before his imprisonment, are even more fleeting. In Kan’an’s memory, Hind becomes a “flash of lightning bestowing you with the memory of a wound.” These two women are compared by the narrator to bookends that mark the beginning and end of Kan’an’s underground existence. When he is captured by the Israelis, Kan’an consolidates “his alliance with his revolutionary self” and prepares “to enter into the new phase of confrontation” with the state of Israel, that of a political prisoner. Through this coming-of-age story of a political prisoner, Rafeedie articulates a core narrative within Palestinian prison literature.

Like other revolutionary novels, The Trinity of Fundamentals is imbued with an earnest didacticism. After all, this is not just the story of an individual and his quest for self-fulfillment; it is also the story of the Palestinian people in their resistance to Israeli settler-colonial occupation. With its extended yet instructive historical and political digressions, The Trinity of Fundamentals has more in common with a novel such as War and Peace or What Is to be Done? than with the latest Booker or Pulitzer Prize winners. I mean this entirely in the spirit of praise. The novel’s earnestness and didacticism are out of sync with much mainstream contemporary Anglophone fiction, in which the hero’s quest for self-realization transpires in an inward-facing world that takes scant account of global injustices.

Another quality that distinguishes this book from most English-language novels is its unique blend of fact and fiction. In the introduction, Rafeedie himself describes The Trinity of Fundamentals as a “fictionalized-narrative-of-life-in-hiding novel.” Indeed, in the middle of the story, we are treated to a history of reading from prison. The narrator tells us how literature “nourished” Kan’an and also “strengthened his moral fiber, cultivated his taste for art and beauty, fanned the flames of enmity within him towards the tyrants, boosted his opposition to all manifestations of oppression.” Among the novels that prove foundational for Kan’an’s literary education are the aforementioned The Snow Comes through the Window (1969), by Hanna Mina, and Nikolai Ostrovsky’s Soviet classic How the Steel Was Tempered (1932). Yet the works that inspire Kan’an are not all overtly political; they include works of fiction by the Brazilian writer Jorge Amado and the Saudi Arabian writer Abdelrahman Munif.

Though well-established in Russian and other revolutionary literary traditions, the genre of fictionalized autobiography has yet to establish a foothold in English, which as a whole prefers its facts tightly siphoned off from its fictions. This bifurcation between the political and the personal is very much to the detriment of English literature, as a comparison with the political commitments that animate Palestinian and other Arabic fiction shows. In Rafeedie’s words, this separation of the political from the personal has led to a society in which the “liberal quest to bury revolutionary concepts and points of departure, and to sow doubts about them has reached unprecedented lengths.”

The evolution of Kan’an’s revolutionary consciousness during his life underground acquires particular acuity amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza. Rafeedie makes us think seriously about what it means to dedicate yourself to a cause, and to sacrifice everything for collective liberation. As Kan’an advises Muna when she casts doubt on his revolutionary struggle: “Arm yourself with determination and that will make the impossible possible.” By arming us with determination, The Trinity of Fundamentals becomes a novel not just for our own times but for every future generation. May it help us collectively imagine a future in which the revolution that Kan’an struggles for achieves its goals.