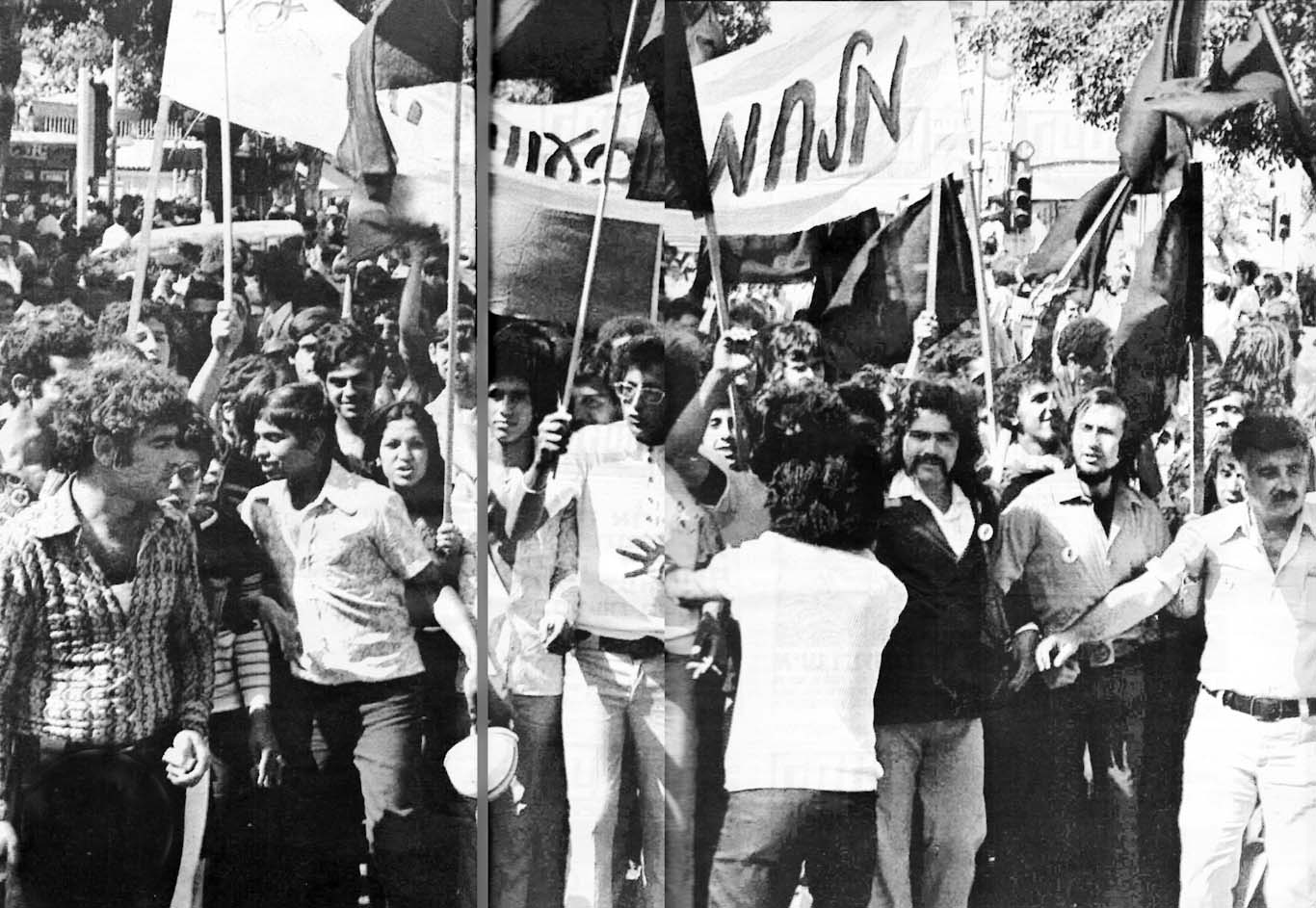

In the 1970s Israel’s Black Panthers rocked the establishment and brought the rampant discrimation against Arab Jews to light. Their legacy contributed to the work of subsequent scholars including Sami Shalom Chetrit and Ella Shohat, among many others.

Israel’s Black Panthers: The Radicals Who Punctured a Nation’s Founding Myth by Asaf Elia-Shalev

University of California Press

ISBN 9780520294318

Ilan Benattar

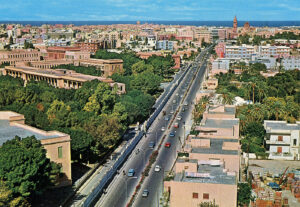

The Moroccan Jewish Marxist Abraham Serfaty (1926-2010), a longtime political prisoner sometimes referred to as “Morocco’s Mandela,” was one of the 20th century’s most insightful observers of Moroccan Jewish affairs. This in spite of the fact that by the late 1960s the majority of the community — numbering between 200,000-250,000 around mid-century — had relocated to a country where he would never set foot, the State of Israel. As a vigorous anti-Zionist and an unrepentant revolutionary, his writings on Israel bristle with fury over two homelands lost: Palestine for Palestinians and Morocco for Moroccan Jews. In his various essays on the “Zionist entity,” he devotes particular attention to the dual position occupied by what he terms its Arab Jewish “colonial minority,” a demographic in which Israelis of Moroccan origin feature prominently. This “colonial minority,” according to Serfaty, functions as both “an instrument of oppression against the Palestinian people and as cannon fodder in the service of the expansionist aims of the American-Zionist rogues in the Middle East.”(1)

In 1982, while incarcerated for his underground political activities — he was in jail from 1974 until 1991 — Serfaty penned “An Address to the Wretched of Israel,” which he dedicated to “my Arab Jewish brothers and sisters.” Serfaty writes with particular verve about the protest movement that had emerged from within this community a decade earlier:

Recall, my brothers, my sisters, how the protests of the Black Panthers some twelve years ago shook the regime far more than twenty electoral defeats could have. And yet, you expressed your anger with no organization, without a program, and without definite objectives. Consequently, this historic movement was able to be infiltrated by political professionals and thereby sink into the quicksand of the game that is Israeli “democracy.” A democracy that resembles that of Ancient Rome, one in which you yourself are the plebeian, kept apart in slums and in ignorance. A democracy that for you signifies oppression and which for the Palestinian people signifies massacre.(2)

Asaf Elia-Shalev’s new book, Israel’s Black Panthers: The Radicals Who Punctured a Nation’s Founding Myth, offers a granular history of the movement that Serfaty eulogized. Over 20 tightly constructed chapters, Elia-Shalev traces the Israeli Black Panther phenomenon from its inception among a group of Moroccan Jewish young men in the West Jerusalem neighborhood of Musrara, through its height from early 1971 until the October War of 1973, into its splintering in the lead-up to the 1977 Israeli parliamentary elections (which saw the historic defeat of Israel’s Labor Zionist political bloc), and finally, across its afterlives in the disparate paths taken by former leading personalities. According to Elia-Shalev, through the history of this protest movement by Mizrahim — literally “Easterners,” an Israeli term for Jews of Middle Eastern and North African origin — we might glimpse “the roots of the country that Israel has become.”

A staff writer at the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Elia-Shalev narrates events with careful attention to interpersonal drama and local color. It is this foregrounding of the human element, over and above the more familiar themes of regional geopolitics and the global cultural currents of the early 1970s, that distinguishes Israel’s Black Panthers. The sequencing of events and their attendant significance owes much to earlier research on the subject, namely Sami Shalom Chetrit’s The Mizrahi Struggle in Israel (2006) as well as sociologist Deborah Bernstein’s 1976 doctoral dissertation, “The Black Panthers of Israel, 1971-1972: Contradictions and Protest in the Process of National Building.” Elia-Shalev’s distinct contribution lies in his combing through thousands of news articles in English and Hebrew regarding Israel’s Black Panthers, revisiting the limited declassified Israeli police files on the group, and, most importantly, collecting the extensive oral testimony of one of the movement’s key figures, Reuven Abergel (1943-). The resulting work amounts to an accessible and briskly narrated history.

Chetrit has noted that the key question of “political relations within the Mizrahi struggle” concerns situating itself vis-à-vis the Israeli state and its animating ideology of Zionism, particularly along a spectrum “ranging from identification and integration to protest and alternative ideology.”(3) Although Elia-Shalev is clearly attuned to this dynamic, his engagement with it is somewhat uneven and, at times, outright evasive, suggesting a hesitation to step outside of the source material and assess the ideas therein with substantive analytical categories of his own. While carefully outlining the social, economic, and cultural marginalization of Israel’s “underclass of Mizrahi citizens,” the phenomenon that gave rise to the Panthers, the work betrays an almost studied ambiguity opposite the question of Palestine and Palestinians. In a sense, this may be a matter of form following content, a product of the tension inherent to the political project undertaken by the book’s titular subjects. The Israeli Black Panthers, Elia-Shalev notes, furiously criticized their country’s political establishment, yet also evinced “a genuine and prevalent desire to belong to a collective Jewish society,” clinging “to displays of loyalty and belonging.”

Even so, it seems clear that the relative silence on Palestine is symptomatic of something more profound on the level of method. In one of the book’s few programmatic statements, we learn that Elia-Shalev prefers considering the Mizrahi question apart from the Palestinian one. “To the extent the story represents an indictment of Israel,” he writes, referring to his treatment of the history of the Israeli Black Panthers, “it does not reproduce the most common critique, which tends to come from a Palestinian perspective.”

What, precisely, does the author mean here? To what extent is it possible to meaningfully “indict” Israel without also reproducing “the most common critique” leveled at the state? This is among the most pressing issues to arise from Israel’s Black Panthers.

In order to approach the question of whether it is indeed possible to offer a meaningful “indictment” of Israel that does not replicate the “Palestinian perspective,” a brief reconstruction of the relevant history is in order. Following Israel’s establishment in 1948 and the Palestinian Nakba, the permanency of Jewish life in the surrounding region was seriously imperiled. Over the coming several decades, approximately three quarters of these diverse populations — numbering just under one million by mid-century — came to resettle in Israel. This complex historical process can in no way be reduced to a coordinated regional campaign of ethnic cleansing, to the inevitable expression of interminable anti-Jewish hostility, or to the overpowering allure of the Holy Land, of Erets Yisrael. In truth, the nature of these population movements varied widely from country to country in character, scope, and pace — from a rapid and legally sanctioned move toward mass-expatriation in Iraq, to a more drawn-out process in Morocco that was often preceded by extra-legal mechanisms. Ultimately, these new arrivals from the Middle East and North Africa found themselves in a state dominated by Ashkenazi Jews of Central and Eastern European origins. It was from within their midst that Zionism — i.e., modern Jewish nationalism — had originally emerged as one response among many to the intertwined cultural and political crises of late nineteenth century European Jewries.

The absorption of North African and Middle Eastern Jewish communities in newly established Israel was characterized, in the words of Chetrit, by a series of “criminal shortcomings.”(4) The reality of these “shortcomings” is today widely acknowledged. Current debates tend to revolve around the question of whether sustained neglect and under-resourcing of Mizrahi Jewish populations was a deliberate policy on the part of the Ashkenazi Zionist establishment or if it was the unintentional byproduct of racist and Orientalist attitudes coupled with the harsh realities of austerity policies during Israel’s early years. Mizrahi protest movements appeared almost as soon as the communities themselves were transplanted to Israel, with leaders who often emphasized Mizrahi-Arab solidarity.(5) The difference between those earlier Mizrahi-led protests and the Black Panthers, according to Elia-Shalev, is that the Panthers did not have established party affiliation or ideological fealty. The young Panthers of Musrara, originally a Palestinian Christian neighborhood depopulated of its former residents during the Nakba, were almost entirely first-generation Moroccan immigrants. In their experience, life in Israel had been characterized by extreme want: overcrowded housing, infrastructural underdevelopment, underemployment, severe malnourishment, and, perhaps most importantly, criminalization and violent abuse at the hands of the Israeli police. “For a generation of Mizrahim of a certain socioeconomic class,” writes Elia-Shalev, “the Panthers represented a rare public airing of one of the gravest pains of their lives: the feeling of devotion to a country that seemed to reject them.”

The anger of the “Musrara set,” as Elia-Shalev refers to them, found a political language primarily through interaction with dedicated municipal social workers and with young Ashkenazi Israeli radicals within the orbit of Matzpen, an anti-Zionist communist group. Both these social workers and Matzpen were deeply influenced by the New Left and, in particular, by the wave of Black radicalism then shaking the United States. Elia-Shalev presents several possible origin stories for the decision by the Musrara Moroccan immigrants to call themselves “Black Panthers” — aside from the obvious homage to the African American revolutionary group. On balance, it seems that the name was intended to give expression to a deeply felt and hyper-localized sense of blackness: Mizrahi Jews were often termed shvartse khaye, “black animal,” by Ashkenazi Yiddish-speakers. Perhaps more importantly, it was intended to be provocative, to ruffle feathers. So it did.

In the lull between the ceasefire that ended the War of Attrition in August 1970 and the outbreak of the October War of 1973, there appeared a rare opportunity on the Israeli domestic front to address “social” issues. Within this micro-era, the Black Panthers quickly reached the height of their activity. Early 1971 saw a series of protests, community actions, and feverish organizing, mainly centered in Jerusalem. Heavy-handed police repression and public vilification were almost instantaneous. Nonetheless, the Ashkenazi Zionist establishment, headed by Prime Minister Golda Meir, quickly came to recognize the grievances raised by the Panthers as something approaching an existential issue. Social turmoil within Israeli Jewish society was a dangerous deviation from the Zionist ethos, which portrayed the “ingathering of the exiles” as a redemptive and unifying process. For Meir in particular, who had played a central role in molding state welfare policy and had long insisted on her socialist egalitarian bona fides, charges of anti-Mizrahi discrimination were a personal affront.

According to Elia-Shalev, “[u]nlike the American originals, the Israeli Panthers started out believing they could effect change from within the system.” Abergel, the Panther leader on whose testimony Elia-Shalev relies heavily, was one such moderating voice. In a surreptitious application to register as a charity with the Israeli Interior Ministry, Abergel described the Panthers’ mission as “transforming the regime in Israel so that it would become a country for one people without regard to race and with no discrimination among the groups that constitute the Jewish nation.” In other words, “the regime” is not illegitimate so much as it is insufficiently inclusive of all who claim membership in the Jewish nation. The basic category of political belonging is not citizenship, rather, it is Jewishness.

In spite of vigorous repression by the police and political establishment, in a matter of months government purse strings started to loosen. Significant increases in social spending were clearly meant to assuage the Panthers, whose grievances revolved around the underfunding of marginalized Mizrahi communities, demonstrating decisively that the powers that be considered intra-Jewish social turmoil an unacceptable risk. This is what Serfaty meant when he asserted that the Panthers “shook the regime far more than twenty electoral defeats would have.” The 1972 government spending bill came to be known as “The Budget of the Panthers.” To cite two examples among many, and as noted by Elia-Shalev, both the Ministry of Social Welfare and the Ministry of Welfare received a 20 percent budget increase. It is difficult to imagine a scenario in which the Israeli state would respond in this way to demands made by groups that are not part of “the Jewish nation,” regardless of whether or not they hold Israeli citizenship.

The extent to which the Panther movement inadvertently contributed to the historic defeat of the Ashkenazi Labor Zionist establishment in 1977, a defeat brought about by the overwhelming support of the Mizrahi public for the right-wing Likud party, has been hotly debated. In both academic and popular writing on the topic, the Likud-Mizrahi confluence is often described as something like a marriage of convenience. According to Elia-Shalev, “[t]he Ashkenazim of Likud and the Mizrahi immigrants whose honor had been stolen were natural allies against a common tormenter.” This “marriage of convenience” thesis seems more a prescriptive argument than a cogent historical analysis. It rests on the strong implication that this marriage ought to be annulled and, concomitantly, that Mizrahi votes for Likud are not the product of true political conviction so much as acts of protest resulting from pre-political “grievances” against the Ashkenazi Zionist left. Regardless of how this reaction to the Israeli political class might be characterized, engagement in establishment politics has tended to result in more of the same. On the theme of Mizrahi political organizing in Israel, Lana Tatour reminds us to distinguish between “resistance to Ashkenazi hegemony and resistance to Zionism as a supremacist settler colonial project. […] While the former is a project of state reformism premised on a demand for inclusion as equals into the settler regime, the latter one radically demands both decolonisation and deracialisation of the Israeli state.”(6)

In “The Invention of the Mizrahim,” a signal essay first published in the Journal of Palestine Studies, Ella Shohat calls for a “de-Zionized decoding of the peculiar history of Mizrahim, one closely articulated with Palestinian history.”(7) For Shohat, to consider the Mizrahi past apart from the Palestinian past is, regardless of intent, to accede to a Zionist way of thinking. Yehouda Shenhav has referred to this sort of tendency as “methodological Zionism,” which he defines as “an epistemology where all social processes are reducible to Zionist national categories.”(8) Here it behooves us to disaggregate the analogy — implied by the name “Black Panthers” — between the Black liberation struggle in the US and Mizrahi politics in Israel. Although they were treated by the Ashkenazi Zionist establishment with condescension and at times subjected to outright dehumanization, Mizrahi Jews were always intended to be full citizens of the Jewish state. Even if the most chauvinistic among Ashkenazim held them to be something less than proper national subjects, they might still become so by way of necessary tutelage. On the other hand, the kidnapped Africans brought across the Atlantic for a life of slavery were considered by their tormentors as something less than proper human beings — they were property. Their full inclusion as political subjects endowed with citizenship rights was nothing short of inconceivable. “In Israel,” Patrick Wolfe reminds us, “religion operates as a racial amnesty.”(9) For Black Americans, even with the benefits of citizenship, no such racial amnesty has been forthcoming.

This should help us understand why the project of state reformism the Panthers demanded led quickly to tangible developments following an initial period of severe state repression. After all, they were calling on the state to live up to its own expressly and repeatedly declared “ideal” as a homeland for the entire Jewish nation. In other words, their protest employed the conceptual grammar of the Israeli state. True, they declared to the world that, as Elia-Shalev puts it, “something had gone very wrong in the Zionist project.” Yet a crucial point must be made here — a category distinction. The focus of the Israeli Black Panthers’ political critique was not so much the Zionist project itself, the fundamental justice of which remained largely unassailable within their ranks, but rather the sustained mistreatment of Mizrahim meted out by Israel’s negligent political class.

To return to the question posed earlier in this essay: What does it mean to “indict” Israel without reproducing “the most common critique,” namely a “Palestinian perspective”? It appears to entail construing the Israeli Black Panther phenomenon as a standard movement for ethnic inclusion in a more or less average liberal democracy. However, Israel’s nature as a settler society is such that all fundamental political categories rest on the question of Palestine and the Palestinian struggle. This conceptual and historical centrality comes into especially sharp focus when we consider the issues confronted by Israeli Jewish populations that possess deep and indelible connections to the surrounding Arab world. To articulate Mizrahi history apart from a Palestinian perspective is to sever the organic ties which bind a densely connected web of issues. An indictment of Israel might well emerge from such an approach, but it would inevitably be an indictment that the state, to return to Serfaty, can handily bury in the quicksand of Israeli “democracy.”

(1) Abraham Serfaty, “Le sionisme : une négation des valeurs du judaïsme arabe,” in his book Ecrits de prison sur la Palestine (Arcantère, 1992). [Emphasis in the original.] My translation.

(2) Serfaty, “Adresse aux damnés d’Israel,” Ecrits de prison sur la Palestine, 31. [My translation. For a slightly different translation, see: https://www.historicalmaterialism.org/article/letter-to-the-damned-of-israel/.]

(3) Sami Shalom Chetrit, Intra-Jewish Conflict in Israel: White Jews, Black Jews (Routledge, 2009).

(4) Chetrit, Intra-Jewish Conflict in Israel, xi.

(5) See Bryan Roby’s The Mizrahi Era of Rebellion: Israel’s Forgotten Civil Rights Struggle, 1948-1966 (Syracuse University Press, 2015).

(6) Lana Tatour, “The Israeli left: part of the problem or the solution? A response to Giulia Daniele,” Global Discourse 6, no. 3 (2016), 487-492.

(7) Ella Shohat, “The Invention of the Mizrahim,” Journal of Palestine Studies 29, no. 1 (1999), 5-20.

(8) Yehouda Shenhav, The Arab Jews: A Postcolonial Reading of Nationalism, Religion, and Ethnicity (Stanford University Press, 2006).

(9) Patrick Wolfe, Traces of History: Elementary Structures of Race (Verso Books, 2016).