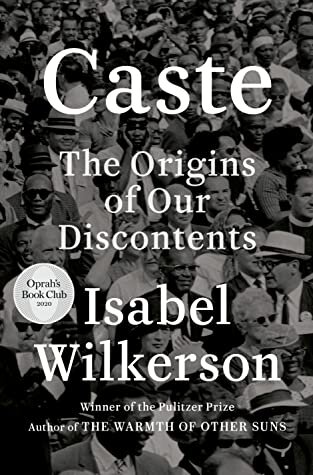

Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents by Isabel Wilkerson

Random House (2020)

ISBN 978-0593230251

Monique El-Faizy

It’s impossible not to think about race in relation to the United States these days. Kamala Harris, half-Jamaican, half-Indian, has been elected vice president. The country has been convulsed by videos of black men being killed or otherwise abused at the hands of police officers, of white people exerting their privilege and by the resulting Black Lives Matter protest movement. Having a president who routinely dog whistles to white supremacists heightened racial tensions all the more.

Isabel Wilkerson’s important book, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, comes, then, at a particularly salient time. But Wilkerson goes beyond the usual analyses of race in America and brings in a new dimension by looking at race through the lens of caste, which she describes as “a fixed and embedded ranking of human value that sets the presumed supremacy of one group against the presumed inferiority of other groups on the basis of ancestry.”

The two are linked, she argues, but not the same. “Race, in the United States, is the visible agent of the unseen force of caste,” writes Wilkerson, a Pulitzer-prize winning former journalist and the author of The Warmth of Other Suns, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction. “Caste is the bones, race is the skin.” In other words, we focus on race because we can see it, but caste is what gives racism form.

It’s a subtle paradigm shift that makes sense of social constructs in the United States in a fresh way. For those who have read Ta-Nehisi Coates, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Robin DiAngelo or any number of other authors on this subject, the facts that Wilkerson lays out in the book won’t be new, so much as they will be presented in a different manner.

By looking at American history through the lens of caste and comparing the US system with the caste structures in India and Nazi Germany (which used American racial purity laws as the basis for its own), Wilkerson gives the reader a different framework with which to consider both America’s history and its present. Each of the three nations “relied on stigmatizing those deemed inferior to justify the dehumanization necessary to keep the lowest-ranked people at the bottom and to rationalize the protocols of enforcement,” she writes.

In the United States, African-Americans have had the same social standing as the untouchables in India—for many years, quite literally, Wilkerson argues, providing many examples of white people refusing not only to touch black people but to even share a drinking fountain or use a swimming pool a black person swam in.

But Wilkerson speaks not in terms of black and white—noting that race is a social construct and that skin color is as arbitrary a way of sorting people as height or eye color would be—but of dominant caste and lower caste. This schema is particularly interesting when considering how immigrants find their place in US society and made me think of the integration of my own parents, my blond-haired, blue-eyed Dutch mother and my Egyptian father, and what that mixed heritage means for me, who doesn’t fall comfortably into either camp, in terms of American caste structures.

Wilkerson writes about her own experiences as a woman in dark skin, about being the Chicago bureau chief for the New York Times but having a store manager she was going to interview dismiss her as wasting his time because he was expecting an important journalist; about being treated differently from other passengers while sitting in the first-class section of an airplane, about being virtually ignored in restaurants, and being followed by DEA agents on a rental car shuttle. Who she is, and what she does for a living and her career accomplishments can be erased by the color of her skin.

“It explains everything that is happening today,” one of the many friends I urged to read the book told me after finishing it. Caste is, quite simply, essential for anyone trying to understand the upheavals of our time and their American provenance.

At the core of Wilkerson’s book is the argument that the United States was constructed on a profound injustice that has not been addressed or atoned for. The caste system that endures today has been with us for 400 years, she writes, beginning after the first Africans arrived in the colony of Virginia in the summer of 1619. Caste is baked into the American DNA.

The book is unflinching, particularly in its portrayal of the brutality of slavery in the US and in its implicit condemnation of the ordinary citizens who not only stood by but revelled in the complete dehumanization of their fellow humans. Americans don’t get off more lightly than their counterparts in Nazi Germany. Wilkerson describes the carnival-like atmosphere at many lynchings and the souvenirs that people took home from them. She also describes in detail the gruesome medical experiments done on black bodies that rivalled those conducted by Nazi doctors on Jews. It is a slice of American history that has been largely sanitized.

Perhaps the sharpest point of the book comes when Wilkerson talks about the reckoning done by Germany over its Nazi past, and the lack of an equivalent in the United States. At the core of Caste is the argument that the United States has not addressed or atoned for the profound injustice on which it was built. Much of the violence inflicted on enslaved Africans were “tortures that the Geneva Conventions would have banned as war crimes had the conventions applied to people of African descent on this soil,” she writes.

But they do not, and whereas Germany has many monuments to the victims of Nazi crimes and none to the perpetrators of those crimes, we in the United States are still arguing over the removal of monuments to those who perpetrated and defended what can only be seen as crimes against humanity. “In Germany, displaying a swastika is a crime punishable by up to three years in prison. In the United States, the rebel flag is incorporated into the official state flag of Mississippi,” Wilkerson notes. Germans who had not yet been born when Hitler came to power continue to bear the burden of responsibility for their ancestor’s misdeeds; a similar reckoning has yet to take place in the United States.

A movement of reconciliation is long overdue, but as the political arena has illustrated recently, much of America is far from being able to consider our own history with an honest gaze. Wilkerson ends Caste on a hopeful note, urging radical empathy. After finishing the book, though, I find it difficult to share her optimism. Our current political cycle has shown that white power will protect itself at almost any cost. Until we as Americans can take an unblinking look at the basis of the inequalities that plague our nation, we will be unable to change them.