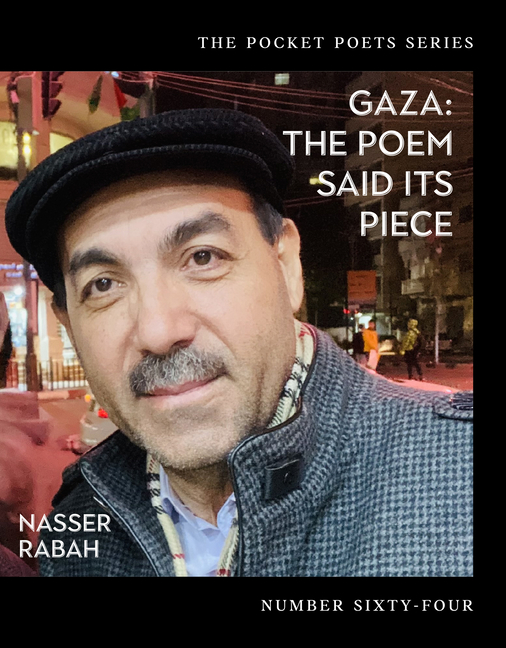

Gaza: The Poem Said Its Piece, by Nasser Rabah.

Translated by Ammiel Alcalay, Emna Zghal, and Khaled Al-Hilli

City Lights Books 2025

ISBN 9780872869127

Eman Quotah

It is perhaps rare that a translator’s note makes the reader cry. But in the case of a collection by a contemporary Gazan poet, writing and living through genocide, tears were inevitable for this reader. Not tears of pity, but tears of concern, anger and empathy when I think of the conditions under which poets are making art, journalists are reporting on what they are living through, and people in general are just trying to survive.

The moving note in question comes at the end of Nasser Rabah’s first collection translated into English, Gaza: The Poem Said Its Piece or ((غزة: قالت القصيدة كلمتها))

Translated collaboratively by Ammiel Alcalay, Emna Zghal, and Khaled Al-Hilli, this bilingual book is Number 64 in City Lights Books’ legendary Pocket Poet Series, which for 70 years has given us iconic, groundbreaking works like Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems. Rabah’s poetry is in its own way just as revolutionary. Mosab Abu Toha — perhaps Gaza’s most well-known living poet to today’s English-speaking poetry audience — has called Rabah the essential Gazan poet.

In their note, the translators write: “The process of completing this translation was not an ordinary experience, limited to the literary tasks at hand. We worked with a sense of urgency, in touch with Nasser whenever and however possible, and our relationship to him and his family became that of extended kin. …. There was a long and terrifying period of no contact when the family was displaced, then joy at news of their safety.”

Any translator working with a living Gazan poet during this time of genocide — and for years before — will have had a similar experience.

Most of the poems in Gaza: The Poem Said Its Piece, come from Rabah’s earlier Arabic collections, but some were written on the Notes app of his phone during the current Israeli assault.

“Given that his books published in Arabic are not easy to find,” the translators write, “we hoped to present this work in a bilingual edition, for readers in Arabic who are not yet familiar with it.”

Rabah’s poems combine melancholy and erudition; classical grammar, diction, and vocabulary and breezy, colloquial storytelling; Quranic references and a modern sense of humor and horror. There’s a formal informality to the verse, a constricted freeness.

In “Water Thirsty for Water” ((ماء عطش لماء)) he writes:

It just so happens that I gather emptiness in my shirt pocket

and run like I have things to do or I’m chased by some

illusion, emptiness might exchange greetings with me and then we

part ways at the first line of a new poem …

يحدث أن ألم فراغاً عميقاً بجيب القميص، أركض كأن لدي مشاغل أو

أن وهما ما يلاحقني، وقد يبادلني الفراغ التحية؛ لنفترق عند ناصية

قصيدة جديدة …

One can see in the side-by-side original poem and translation that Rabah’s Arabic is more economical than the English; that the يs of the first line, and the ق of عميقاً are echoed in the start of the third line’s قصيدة جديدة. In the translation, we find a raft of R’s, then the E’s and P’s of the third and fourth lines.

I make these comparisons not to knock or critique the translators’ choices (though I might not always have made the same ones), or to prize one language over the other, but rather to highlight what monolingual English readers might not be looking for, at least not foremost, in translations of Palestinian texts: translated music, rhythm, poetic grace notes, alliteration, the construction of sentences, the choice of words.

The translators say they have attuned themselves to “bending English toward the syntax, rhythm, and idiosyncrasies of Arabic” because of the role American English plays in “enabling so many of the distortions in how Palestine is depicted on the world stage.” At the same time, not wanting to “exoticize the original,” they say, “we have sought every available nook and cranny where freedom remains” in American English, a language that has been “sapped by the surround sound of propaganda.”

Translator and Arabic literature scholar Huda Fakhreddine has insisted that “Palestinian literature is not literature for times of crisis, and its study is not an afterthought or a ‘safe’ way to show solidarity.” Reading Rabah’s “Heart-Shaped Cake” ((كعكة على شكل قلب)), I am pulled not just into the long tradition of Arabic poetry to which Rabah’s verse belongs, but also into a local poetic ecosystem:

On my birthday I buy a cake shaped like a heart,

every time I buy one I remember “I’m a pie-maker,”

a poem by Bassem al-Nebrees, and I smile.

I remember he made hundreds but never tasted one—

his blood sugar wouldn’t let him …

في يوم مولدي أشتري كعكة على شكل قلب

كلما اشتريت واحدة أتذكر ((أنا صانع تورتات))

قصيدة ((باسم النبريص)) فابتسم.

أتذكر أنه صنع المئات منها، ولم يذق واحدة؛

فسكره لم يسمح …

Using the weak tool at my disposal — Google Search — I learn that al-Nebrees is a Gazan poet now living in Antwerp, Belgium. The beautiful title of his poem ((أنا صانع تورتات)) seems oddly translated here as “I’m a pie-maker” — when in Arabic تورته (from torte) generally refers to cake. But no matter, Rabah’s poem of homage is about sweetness and loss, memory and regret:

Our heart engraved on the tree

ants and forgetfulness climb all over

قلبنا المحفور على الشجرة

يتسلقه النمل والنسيان

When Arabs generally, and Palestinians more specifically, are dehumanized — as seems to be the rule these days — our literary and artistic traditions, our history, are a balm for me. And Rabah’s short poems are small gifts for a heart wrung dry. Rabah skillfully melds the specific and the universal, the now and the then. The collection speaks from a place of hard-won wisdom and humility, every poem like a clever story told by that uncle or seedo you knew growing up who loved kids and spoke to them with perfect Arabic grammar and diction.

In the title poem, “The Poem Said Its Piece” ((قالت القصيدة كلمتها)), meaning is a mirage, and a poem speaks and moves on, “no longer flute to guide those going to the/prayer of ecstasy, no longer clouds to return my praise …” ((لم يعد ني يدل الذاهبين إلى الصلاة\لم يعد غيم يبادلني المديح …))

The poem said its piece, and moved on, now I sit listless

counting my wounds on its fingers, how many of my soldiers

remain, regret my only captive, my faithful companion,

and the bread of my last supper.

قالت القصيدة كلمتها، ومضت،

الآن أجلس فاترا أعد دلى أصابعها جراحي، وكم تبقى من جنودي

أسيري وحده ندمي، ونديمي، وخبز عشائي الأخير

When the poem has spoken, what else is there to say? What else is there to do but write another? In a recent interview with the Paris Review, Rabah describes composing a new poem, “The War Is Over” ((انتهت الحرب الان)) — one not included in Gaza: The Poem Said Its Piece, and which was translated by Wiam El-Tamami. On knowing when the poem was finished, he tells the interviewer, “Some poems stop growing on their own, and there are others that need to be stopped firmly, so that they don’t fall into unnecessary, gratuitous chatter. So, I sent it off to be translated — thereby declaring its completion!”

How lucky, how blessed are we — those of us who read poems in English and those of us who read them in Arabic and those of us who read them in both languages, that Rabah and other poets of Gaza are still writing — still sending their poems to us. We mourn those who have been martyred, and we pray and take action to keep Palestinians alive.