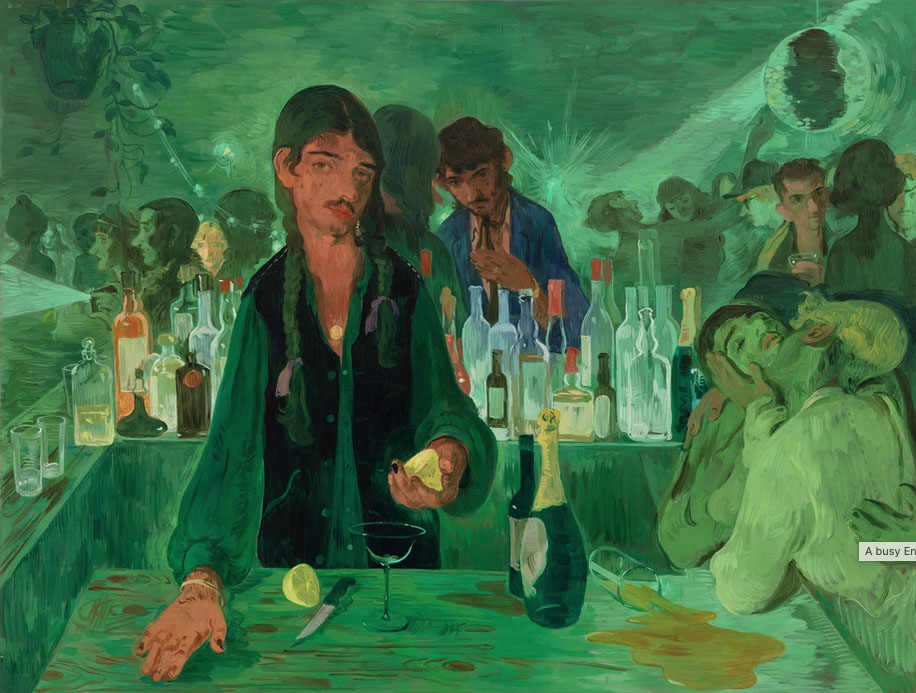

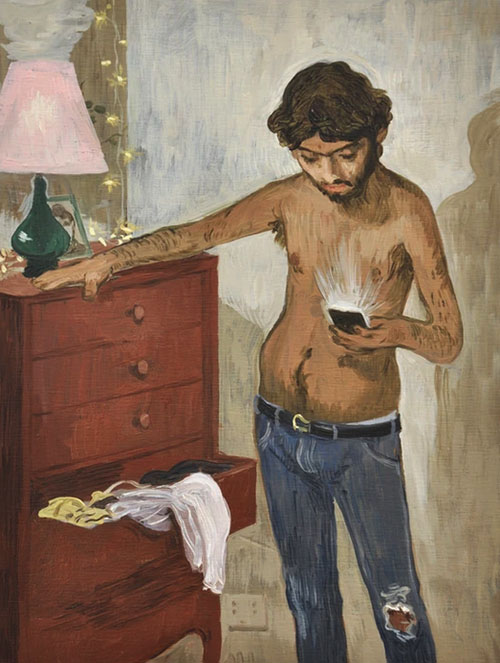

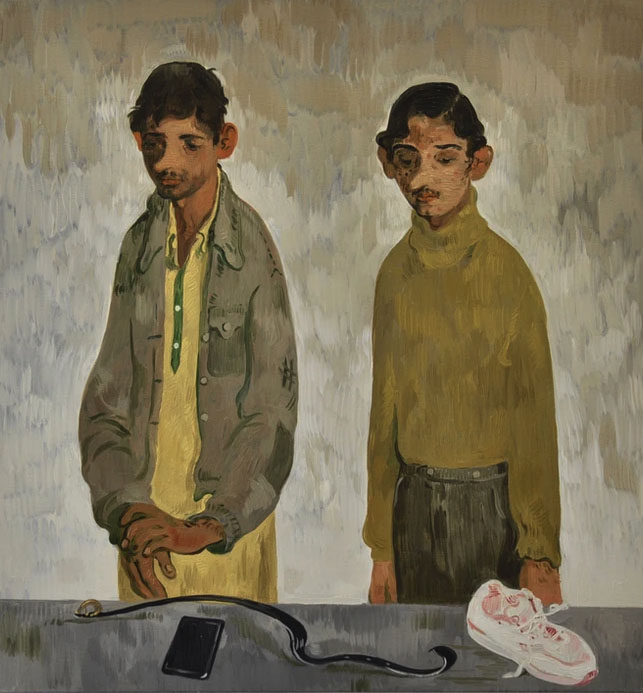

In this exclusive excerpt from Anis Shivani’s forthcoming novel, Patel Mart, Syed Afzal Ali Hayder runs the oldest South Asian grocery store in Houston, Texas. It is the mid-’80s, the city is ravaged by an oil recession, and immigrants from everywhere are struggling. Meanwhile, Hayder has found a lucrative side hustle serving as a conduit for jihad money. Married with a couple of children, he’s also carrying on two affairs simultaneously. How long can he keep his high-wire act going? Will his friends bring him down, or will his delusions catch up with him? | Art by Salman Toor.

Anis Shivani

The next week the skinny guy who had made the delivery before Friday prayers not long ago was back at Patel Mart, wearing the same clothes and looking even more haggard than last time.

“You’re back,” said Hayder, in the middle of unpacking the heavy cartons of dates that had arrived from California early in the morning.

He refused to indulge in self-pity on the hot day, because that wasn’t what Houston was about, what Texas was about, what a Pakistani in America was about. Never complaining was at the top of your list of moral values, so you stayed away from people who infected you with the corrosive sentiment of griping and whining.

“You’re back,” Hayder repeated, “but empty-handed.”

“How do you know?” the man said challengingly. “I could have the money in my car, like last time.”

“You didn’t even drive the old Celica this time, you walked all the way here,” Hayder said pityingly, “so I know you don’t have anything for me.”

“How do you know I came on foot? I could have parked the car out of sight, or behind the shop, it’s a big space.”

“Maybe I have eyes in the back of my head, or maybe I have cameras that scan all over the parking lot. Little screens behind the counter, showing me empty parking spaces, because who shops on Friday mornings? And look at your shoes, they’re worn out, all you’ve been doing is walking for a few days, not even taking the bus.”

“That’s ridiculous, you don’t have cameras. I watched you for a few minutes, you’ve been unpacking these cartons of dates for a while.”

“That’s true, very true,” he admitted, suddenly feeling very tired. “Okay, you go ahead and finish the rest of the job then. Empty the remaining cartons and place the boxes of dates on top of each other in front of the aisles closest to the cash register.”

“Okay,” Bakari accepted without much thought; after all, the week before he’d been probing Hayder for a possible job. “Okay, but why are dates so popular still? Ramadan is over, nobody’s going to want them.”

“People acquire habits, which continue even when they’re not necessary — especially when they’re not necessary. It’s like having an appendix.” Hayder probed the part of his tummy where he understood the redundant appendage to be located, and realized with alarm that the flesh there had thickened to the point where he could no longer feel any internal parts. “What function does the appendix serve, except to create emergency surgeries to make the rich doctors at Hermann Hospital even richer? Have you ever been to that hospital on a Friday night? It’s quiet, except for the rare childbirth or two, maternity the order of the day, while the trauma victims, gunshots and throat slashings and drug overdoses, are carted away to Ben Taub Hospital, next door but a world away.”

“I know what it’s like. I don’t want to end up at Ben Taub. I’ve heard horror stories.”

“At least they don’t ask you for payment up front, as long as you have the Gold Card.”

“I hope I never need the Gold Card.”

For some people it was almost as important as the green card, Hayder thought, as he asked Bakari, “Was it like this in the country you came from, the gulf between rich and poor, so close yet so far?”

“What?”

“Oh, I forgot, you said you’re from Baton Rouge, which is another world away, I guess. No state is like Texas, as you can tell. You cross the border to New Mexico or Oklahoma or Louisiana, and suddenly the police presence melts away, and even when you see them they appear a little apologetic and meek without the ten-gallon hat the Texas highway patrolmen wear, and without those heavy murderous boots too.”

“I’m afraid to travel. Too many predators on the roads and highways, everyone wants to take advantage of you.”

“They will if you let them, that’s true. Anyway, it’s about time for a long road trip with my girl and boy, or at least as far as the Hill Country. My wife, you see, she gets antsy on the road. She complains a lot, her legs feel like spiders are crawling over them, her throat feels parched even after downing two bottles of Coke, and her hair will be ruined forever in the air-conditioner’s blast. And she wants me to drive slow, slow, slow. Are you married, Bakari?”

His visitor looked shyly at his feet. “No, not for me.”

“I got married the first chance I got, because I didn’t want to be a long-suffering idiot whom time had passed by. Funny thing is, the older I get the slower time goes by, or rather, it moves by jerks and halts, skips a month here and there, maybe bypasses an entire year, so that suddenly we’re here in 1985. A year after the dreaded 1984, a book I never read, because what can it tell me that I don’t already know?”

“I never heard of that book,” Bakari replied, continuing the unpacking and stacking, and pausing to admire his handiwork.

“Man, did you ever think one day you’d be living in 1985? Everything seems more pasty, more hazy, so that the pictures you’re seeing don’t seem real even when they pretend to be. Spies being arrested right out in the open, and you wonder, is it the FBI staging these events for entertainment value, and are the Russians and Americans and Israelis just one big organization with interchangeable names and faces? Space shuttles barely making it to space, when we had the moon conquered the year after I came to America, so it’s like we’re moving backwards, like we’ve forgotten how to do anything anymore, and we have to start over again. And all of that plotting happens just 30 miles down the Gulf Freeway. Take me to NASA, begs every single visitor from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Burma, Afghanistan. They all want me to take them there, every random brother-in-law I never saw before, every alien guest with fixed demands. They remember every detail of the tape they saw of the astronauts stepping on the moon for the first time, and that was sixteen years ago now. It’s as if they expect Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to be hopping around in their spacesuits on the NASA grounds, maybe even fire up a rocket and take them on a little trip — just to enter space, mind you, nothing so crazy as the moon, not to mention Mars or another planet in the solar system, which as it turns out seems to be impossible for human beings to reach. But this is space city, what do you know, Bakari, my friend, we invented space, we created space, and now I’m unpacking cartons of dates, and so are you, my friend.”

“All done, Mr. Hayder,” his guest announced soon, leaving him impressed by not commenting on his rambling talk. By sharing in Hayder’s rare outburst, he’d laid claim to a form of friendship, whereupon Hayder felt obliged to protect him. “Anything else I can do for you?”

“You can tell me about why you don’t have the money today.”

Had there been a glitch of some sort?

For five years, not long after Reagan was inaugurated, he’d been handling the money, in small quantities at first, and then in larger and larger quantities, more and more frequently, until the quarter percent commission started feeling absurdly excessive. It should be more like a fraction of a tenth of a percent, because the risk he was undertaking was minimal to zero. In a city that had collapsed in on itself, with oil prices headed toward zero, entire streets of houses with foreclosure signs one after the other, and shops being boarded up in places you never thought would fall victim to blight, nobody bothered to look too closely at anything. The police itself seemed to be on holiday.

Last time he’d taken his kids to Astroworld, an octogenarian cowboy had insisted on getting on the most difficult roller-coaster ride, and had disembarked claiming that he had possession of the jewelry of a number of women on the ride. Indeed, that was the case, but how had he pulled off his pickpocketing feat in the middle of a madcap ride?He duly returned his pickings to each of the impressed young women in question, while a park attendant called the police, who wouldn’t show up. Most of the witnesses left, and those that remained weren’t willing to say anything against the grizzled cowboy, because it had been harmless, despite the mystery. And it wasn’t even rodeo season, an obligation his wife had thankfully never warmed up to, otherwise if you were a Pakistani in Houston you must lay claim to appreciating the rodeo, because horses and cows and their shit and farts were the kind of rural simplicity a desi had to appreciate in order to belong. At the rodeo, just as at the San Jacinto Battleground Memorial 20 miles east of downtown, you went as a Pakistani but acted as if the patriotic or cultural significance meant something deep to you, when plainly it didn’t. It was as alien as understanding a mosque ritual would be to a white American.

It was like Christianity, forever alien, no matter how hard you tried, and even if you believed that your own religion encapsulated it. You smiled harder at the monument or rodeo, conscious that your accent was turning a bit more into the absurd Texan accent each day, and you came home sad that you had lost whatever faith you once had in the power of belonging. The mosque was a last desperate shot, and today Hayder would take this young man with him.

“Tell me your name,” he said, trying to free himself of his convulsive thoughts.

“Bakari Aziz Abdallah.”

“What does Bakari mean?”

“It means the successful one.”

Undoubtedly he was homosexual, which didn’t matter one way or the other to Hayder, even if he personally didn’t care for the persuasion. It was entirely beside the point when it came to business and employment. His most charismatic professor at Oklahoma State University had been a flamboyant homosexual who liked to throw parties for his students at his faculty row “mansion,” where people often passed out drunk or on drugs, littering the various porches, the garden, and the roof with their wasted beings, while the professor remained steady and self-assured with his “one special guy” always on his arm, his exclusive date for the evening. The professor yet again drove home his point about intermittent monogamy, and illustrated, by way of the wild party with unmoored attractive men, his own powers of fidelity. He understood financial management better than anyone Hayder had known, far exceeding what was required of him to deliver for the undergraduate course, turning it into a positively sexy subject.

“And are you? Are you successful, Bakari?”

“Probably not, although I’m still alive, so there’s that. It takes a lot to stay alive these days, Mr. Hayder, it’s not like 1975 when you could show up at a disco club all decked out in jewelry and hot pants and some rich chick would take you home because she could care less where you came from. It takes a lot to stay alive now, because people choose to look the other way. I could walk out of here and fall dead on the street and it would be a long time before someone took notice.”

And took you to Ben Taub where you don’t want to end up, Hayder pondered silently, as he said, “What you’re telling me is we’ve gone blind.”

“I guess so. I quit, by the way, since you asked me about the money-handling, the job was too difficult. They were sending me to the worst places in the Fifth Ward, auto junkyards on Liberty Avenue, burnt-out convenience stores on Waco Street, and in the Third Ward too, dope dealers’ shacks on Scott and Calhoun streets.”

“Come on, Bakari, the Third Ward isn’t so bad, the UofH cops keep an eye out all the time.”

“Are you kidding me? It’s a cesspool, worse than anything I ever saw in Louisiana which has such a bad name here. People don’t value life in the Third Ward, they’ll kill you for 20 bucks.”

Hayder thought of his longtime girlfriend Taneesha whose house was just off Scott Street, and knew he couldn’t agree with Bakari’s calumny against the neighborhood, but decided not to make an issue of it.

“And that’s what they’ve got me dealing with, tiny amounts of money I have to pick up and drop off, as if my own life meant nothing,” Bakari went on. “Any of those bastards could get mad at me for no reason and take me out. They don’t need to have a reason, they need a life they can claim as a trophy.”

“A scalp.”

“Exactly.”

“A Bakari scalp.”

“You got it.”

“Look, I can’t hire you here, my two people are more than enough, but I can keep an eye out for you. Have you tried anyone on Harwin yet?”

Hayder meant the long and winding street populated by wholesalers selling household goods, jewelry, watches, fabrics, car parts, small appliances, toys, decorative trinkets, and above all cheap rip-offs of famous brands of every object from sunglasses and purses to shoes and jeans. The street was dominated by Ismailis, generally a few shades less cultured than Saleem Sayani, but all of them dedicated jama’at-khana-goers and admirers of His Highness the Agha Khan. They liked to complain about how there was too much competition, with the Vietnamese and Filipinos and Koreans shamelessly muscling into their own territory, so that it had all gone to hell in a handbasket in recent years. Harwin was perpendicular to Hillcroft, the two streets intersecting close to the 59 Freeway, Hillcroft the retail branch that took care of desis, while Harwin catered to shopowners who bought wholesale as well as the steady run of adventuresome individuals who didn’t mind the lack of bargaining in a wholesale environment. Hillcroft fed people’s stomachs, while Harwin equipped the houses where they shat and pissed, was another way to put the difference.

“Maybe you should have stayed in Baton Rouge,” Hayder said after a period of time that saw Bakari straightening the shelves, spraying the vegetables with the perfumed mist that the customers appreciated, and generally making himself useful by cleaning and spiffing things up. “Bakari, when you were in Baton Rouge, what did you do there?”

“Oh this and that, Mr. Hayder. I prefer the big city, there’s more opportunity here.”

They all said that. Even he had said it once, and probably still felt that way. Even if Mahmood Mustafa, the freelance accountant, landed no better job during the next year than helping out some bankrupt Chinese-Mexican restaurant on Bellaire Boulevard and then got stiffed for payment for his services anyway, he would still believe it. Leticia believed it, Taneesha believed it, all his past girlfriends believed it, his wife believed it, and his daughter wasn’t old enough to believe it yet but once she had a medical degree or something equivalent in hand wouldn’t she believe it too? And by big city they meant a place where they could make themselves known as agents of destiny. They all did.

The desis on Harwin Drive, mostly Ismailis of Sayani’s community, openly spoke the language of colonizing the wholesalers’ row.

“Soon the Chinese will be reduced to this much,” the wholesaler named Ameen Lakhani, owner of the eponymous store, liked to say as he pinched his fingers and spat on them. “You have no idea, Ali, how hard it was in the early years. We were the first ones here, me, my brother Shaukat, his cousin Jamal, and we had to fight every inch of the way. The Chinese don’t like to share prosperity with anyone, with them it’s all or nothing. When we take control of the street, believe me we will share the wealth with everyone. If the Chinese want to come back, they will be welcome. But right now they’re setting the terms: They cut prices like crazy to seize hold of the market, they take losses for years on end to keep competitors out, and the deals they get with freight companies, I don’t know how they do it. They appeal to people’s sense of continuity. You’ve been happy with us, Low Hong Chu Brothers, how long have we been doing business, 20 years? Then why change, why go for the new? I tell you, they’re the most conservative merchants on earth. They keep track of every penny, and their heirs live in constant terror of being disinherited and exiled. It all comes from Confucius, they never got away from that.”

It was this same Lakhani that Hayder drove Bakari to, as Bakari’s body shook in tremors whenever Hayder’s old Datsun bumped over potholes or debris left over by construction crews. The orange cones marking dug-up road graves were a ubiquitous Houston phenomenon, which Hayder hadn’t noticed even in other Texas cities like Dallas, San Antonio, Austin, or El Paso. Crews were still working on road and freeway expansions they’d started when Hayder first came to Houston eleven years ago. You got resigned to it, and one of the signs of a newcomer was when they complained about endless road construction. Hayder also had sympathy for the workers. They needed to make money somehow, and so what if it seemed to come through graft and corruption, because why else would a minor project take years and years? They had to earn money by one means or another, both contractors and workers, and he appreciated that.

They remained blocked for long minutes at an intersection while a dump truck unloaded its contents of what looked like farm-ready soil in the center of the street, and a barechested worker with huge pectorals smoked a cigarette and threw the butt on top of the pile when the truck was finished.

Lakhani had slowly acquired one shop after another in his strip mall, until the entire space, all three sides of it, belonged to Lakhani Enterprises.

“How well do you know him?” Lakhani inquired about Bakari from behind the white Formica counter when Hayder presented him inside the shop. The clutter, dank smell, dim lights, loud fans, slippery floors, and lack of security reminded Hayder of similar Pakistani businesses. “I mean, he’s obviously not related. Not that you’d bring a relative of yours to find work with me, they’re surely all high-powered people.”

“I don’t know him. He just seems to me like an honest worker.”

“How do you know he’s honest?”

“He’s been trusted with large sums of money.”

“How large?”

“Fifty thousand dollars.” Hayder glanced at Bakari and asked, “Or more?”

“Yes, often more.”

Hayder whistled. He’d asked it only as a rhetorical question. So there were others to whom the money was being funneled, as he’d always suspected of course, but it was yet another confirmation that his services weren’t exclusive in the least.

“Honest, and a bit naïve,” said Hayder. “So you decide, but I like him.”

Hayder and Lakhani stared at Bakari as though inspecting a hunk of meat on the auction block, assessing his stamina, strength, intelligence, and wit as though they were experts at mind-reading.

“Some of the work is tough, I don’t know if you’re strong enough.”

“I’m strong enough,” Bakari told Lakhani. “Just try me.”

“Okay, come on Monday. I have to get rid of some people by then, and you can start fresh. You can help unload goods from the trucks that come in, my people will show you how to make it easy on yourself. Just don’t throw out your back. Once you have that injury it never leaves you, you’re never the same again.”

Lakhani came out from behind the counter. Bending himself at the waist and touching his knees with his palms, exactly as in the ruku‘ during namaz, he groaned. “See? I can’t do it.”

“But you just touched your knees,” said Hayder. “I can’t even do it that easily.”

“Yes, but I felt the strain in my back.”

Bakari seemed fascinated by the clocks, watches, radios, toasters, irons, hairdryers, and blenders piled up all around them, everything for the kitchen and home, often for under ten dollars. He picked up a few items and inspected them carefully, which greatly pleased Lakhani.

They talked about the collapse of a wing of the new Ismaili jama’at-khana under construction on Wilcrest, Lakhani blaming it on the recent rains, as though Houston contractors didn’t have frequent experience with it. Lakhani said he was grateful not to have anything to do with a convenience store, because yet another Pakistani had been shot to death at a 24-hour store, the iron bars and occasional security patrols having done nothing to dissuade the black intruder from killing one of their own compatriots for a measly take from the cash box. The killings of the desi cashiers had been a regular occurrence, long predating the oil crash, as constant a fact of Houston life as the endless construction.

Bakari, who had been listening in on the conversation, remarked, “It’s just who we are as a people. Everything is a criminal enterprise, whether we want to admit it or not.”

“Even Patel Mart?” asked Hayder. “Even Lakhani Enterprises?”

“Money itself is illegitimate.”

“It’s the only legitimate and fair thing in the world,” Lakhani refuted him, “the only honest way to measure effort and enterprise.”

But Lakhani didn’t seem too disturbed by what Bakari had said. And who had Bakari meant by “we”?

“Time for namaz, yaar,” Lakhani told Hayder. “It’s that time again.”

“Aren’t you coming?”

“In a bit, I will,” said Lakhani, “in a bit.”

Obviously he had little intention to make it to the congregational prayer, even if some Ismailis and Shia’s, Sayani most prominently, did go to Hayder’s Sunni mosque.

As was the wont of the namazis at Al-Noor masjid, just because of the fact that Bakari was Hayder’s guest that day, he got the star treatment. Bakari was accepted like one of Hayder’s hard-to-remember brothers-in-law, each of whom had made a brief requisite appearance at the mosque before heading on to his desired American destination and disappearing somewhere on the massive continent. If Lakhani fell through, some other employer would emerge as a contender. Bakari would find a job. It was Hayder’s mission to see to it that it happened.

After the prayers, Asif Alawi corralled Bakari to tell him the latest developments in the saga of one of his nephews being snagged by the British immigration system.

“You see, we’re supposed to be members of the Commonwealth, all the former British colonies, but in reality it means little. Unless you’re West Indian, and then it counts. But not for Pakistanis and Indians, oh no! Are you West Indian, my friend? From Trinidad and Tobago by any chance?”

“No, I’m from New Orleans, by way of Baton Rouge.”

“Oh what a terrifying city New Orleans is!” Alawi moaned. “I’m a grown-up man and I’m not frightened of much, but they call it sin city for a reason. Total lawlessness, anyone can do whatever they want, solicit a grown man for sex in front of his grandchildren, offer drugs as if they were selling candy, and the police always look the other way.”

“Actually Las Vegas is called sin city, not New Orleans.”

“The same principle though, see no evil, hear no evil.”

“They do call it the Big Easy.”

“Big and Easy, there you go. Too easy, my friend Bakari, too easy.”

“I never felt safer than in New Orleans.”

Alawi looked at him strangely. “I don’t think so, my friend. Pickpockets operating in clear daylight, businessmen in shabby clothes leering like beggars, and everyone a gambler and sharpshooter and fast-talker. I believe it when they say the conspiracy to kill JFK was hatched in New Orleans, I believe it.”

“So you don’t buy the lone gunman theory?”

Alawi laughed. “Is there anyone in the world who does?”

Saleem Sayani, whose lesser compatriot Ameen Lakhani had just given Bakari a job, seemed hugely amused by Bakari’s odd displacement, as he was interrogated by one or the other namazi who felt obligated to do so because he was Hayder’s friend. Some of the women in their fluttering green dupattas were glancing avariciously toward him. Hayder knew that no matter how fit and athletic a desi man was, there was something about a black man — or one who looked black enough — that made him outshine any desi man in physique. It was the dark mythology of uncontainable sexual prowess that had gripped the desi woman’s imagination just as it enthralled the white woman, and there was no competing with it. He’d seen it happen even with 70-year-old black men, derelicts and drunkards, barely able to put two sentences together, stinking of cheap liquor and the rank odor of Houston summers. Even they held the advantage when it came to being perceived as pure sexual beings. Even his diminutive Patel Mart hire, Dawood, even he was treated as a sexual champion by hibernating wives, perhaps as their “ghulam,” the harem slave who would fulfill their every fantasy.

“Where do you live, Bakari?” Hayder asked him later in the afternoon when most of the namazis had left, having paid their dues for the ongoing global jihad, everything aboveboard and legitimate of course. “I’ll drop you off.”

“Oh don’t worry, Mr. Hayder. I live right behind the mosque, at Gulfton Apartments. I moved in a couple of days ago, they were giving me a very good break.”

Gulfton Apartments was where Leticia lived.

“I know someone who lives there. What’s your apartment number?”

“A-305.”

“I see.”

It had to be that way, of course. A-306 was Leticia’s apartment. Bakari would be able to hear them banging each other if he put his ear to the wall.

Hayder let him get a good lead before he walked toward Gulfton, remembering the juvenile imam’s pitiful contention that India would soon yield up Kashmir, because Pakistan was now the country in favor with world capitals, and there was no way India could match “us” in those escalating sweepstakes.