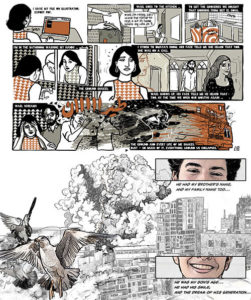

The toll of Israel’s latest onslaught on personal and communal life is severe. In Beirut’s southern suburbs, women mourn their martyrs publicly and privately.

In a small, recently renovated women’s clothing boutique in Dahiye, Beirut’s southern suburbs, Rania sits behind the counter silently, gently smiling hello to me as I enter. Placed on the counter in front of her are two framed photos: one of a young man with a soft smile and glowing face, and a second of Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, the late head of Hezbollah. It’s late January, only two days after the end of the initial 60-day ceasefire that put a stop to the war and halted Israel’s shelling of Lebanon. People are still processing the war and the losses that came with it, and a solemn mood permeates not just the store, but the entirety of the once-bustling Dahiye.

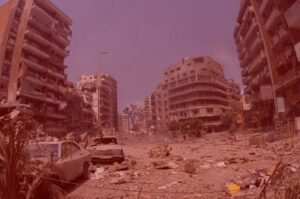

Just like at Rania’s clothing boutique, images commemorating the men who lost their lives fighting in the war — Hezbollah fighters and some civilian volunteers as well — are displayed everywhere in the area: in shops, restaurants, on streets, hanging from balconies, in the corridors of buildings. Over the course of the war (which began on October 8, 2023, when Hezbollah declared itself a “support front” for the resistance in Gaza but ratcheted up in unprecedented intensity in late September 2024), Israel dropped bombs across all of Lebanon. The brunt of its ferocity, however, was concentrated on South Lebanon, the Bekaa, and the southern suburbs of Beirut, the most predominantly Shia areas of Lebanon, or, what Israel likes to call “Hezbollah strongholds.”

In all of these places now, the losses of the community are visible not only in the rubble and destruction left behind, but in the photos of the martyrs which hang everywhere.

In Shia Islam, martyrdom is revered as the highest form of devotion and sacrifice, symbolizing ultimate faithfulness to God and justice. Those who die fighting for their beliefs are honored as martyrs (shuhada), believed to attain eternal life and intercede on behalf of their loved ones on the Day of Judgment. And anyone who dies fighting for a just cause, or falls in the cause of justice, is considered a martyr. Thus, martyrdom is not a political denotation but a spiritual one, signifying those killed in their pursuit of justice.

Oscillating Public and Private Spaces

I’ve spent the last two months in Dahiye, documenting not only the destruction left behind by the war, but the lives left behind in its wake. Specifically, the lives of women, and the different forms and sites of commemoration they have created and preserve, both in the public and the private sphere. In public spaces, the hanging images create sites for collective grief as a community, while in private spaces the survivors left behind — most of them women, children, or elderly — grieve the absence of their loved ones through personal forms of mourning and commemoration. Families huddle together, trying to heal and think about what’s next.

“The war isn’t over yet,” says Randa, 28, an artist. Her family, like so many other families in Dahiye, is originally from South Lebanon, but they moved to the Ghobeiry neighborhood in Beirut’s southern suburbs some 20 years ago, seeking better economic opportunities. Randa keeps pictures of the martyrs she knew personally. She describes how her family lost countless neighbors in the war. “We sit together now as families to try and process what’s next. But the war isn’t over, and we will never leave our land.”

In the first week of February, I shared lunch with a woman and her 25-year-old daughter in their apartment in the Haret Hreik area of Dahiye. They laughed at what look like structural cracks in the walls of their apartment, and thanked God their home was still standing. Later that same day, I took my place among several separate groups of women in a cemetery dedicated to martyrs. Their tears fell silently as they read the Quran and recited prayers over fresh graves. Their grief was still raw and unfiltered, a stark reminder of the recent losses.

The next day, I found myself buying olive oil, jam and pomegranate molasses — different types of “mouneh,” or preserves, from villages in South Lebanon, being sold by Fatme, a woman in her late 60s or early 70s who works long hours daily, selling the goods from her village to help support her family. She beamed brightly when I made my purchase. Fatme told me she has lost countless family members, friends and neighbors to the successive wars with Israel. She accepts their ascension to martyrdom with simple joy. “We are all under the care of God,” she tells me.

As an anthropologist, I’m spending much of my time with women who, despite the devastation around them, are calibrating to daily life, navigating their days with solemn conviction. They speak of loved ones they’ve lost, of homes that are gone, or of their former neighbors, highlighting how interconnected relations between families are in Dahiye. Every single person knows martyrs and families who lost everything. As I move through the devastated streets and neighborhoods of Dahiye — streets that were once bubbling with life, with people coming and going and young men zipping about on scooters — I see mostly women of all ages, trying to reconstitute the things of life, walking past buildings reduced to rubble. I can’t tell if there are more women visible in public spaces now, or if perhaps I’m noticing them more, given that fewer young men are visible than before.

Conviction No Matter What

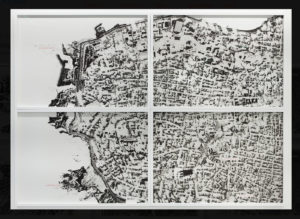

Dahiye was rebuilt from the rubble after being destroyed in the 2006 war with Israel. Now, it is rubble once again. The scale of destruction is significant. According to 2022 estimates from the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Dahiye’s population is close to one million, divided among its five main districts: Ghobeiry, Burj Al Barajneh, Haret Hreik, Hay Al-Sellom (and adjacent Laylaki), and the coastal strip of Ouzai, visible from the airplane when landing in Beirut. Before the Lebanese Civil War, Ouzai was home to some of Lebanon’s most luxurious beach resorts. Today, it is one of the poorest districts of the country. According to a UNDP Rapid Assessment report published in January 2025, the district of Haret Hreik experienced 33% of the total destruction from among Dahiye’s districts.

As I continue my work, I observe above all how the people of Dahiye remain steadfast, largely thanks to their deep faith in God, and in what they perceive to be the justness of their cause. I am reminded that resilience — a word that is too frequently used by Western media to describe that steadfastness of the Lebanese — is not a choice made by them. In the absence of choices, “resilience” is a necessity. It’s called survival with conviction and commitment.

The women hold tightly to their routines, their prayers, and their memories because, in the face of so much loss, they have no other choice. In their eyes, I see both the weight of their grief and their adamant determination that they will rebuild again, even if they have to do it themselves.

A few days after that initial ceasefire period ended, I was leaving a friend’s apartment in Dahiye. I looked up to see a picture of two martyrs taped to the wall outside the front door of the apartment across the hall. Inside the elevator, I found myself standing next to a woman. At the next floor a man entered clutching a photo of a young man. They greeted each other. “I heard about your brother,” she said. “May he rest in the grace of God.” A tear rolled down the man’s face as he nodded his thanks. We continued down to the ground floor where the door opened to four people waiting for the lift: A man, two women, a young girl. They all greeted the man with the photo and offered their condolences. “May he rest in the grace of God.” The women smiled at each other and touched one another’s arms. “See you soon” said one. “Come over for coffee later,” the other replied. They smiled and parted, each going on to the rest of her day. And thus life continues.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

The simple grace of this peace gives those of us who quietly mourn from a distance a much-needed sense of solidarity. Thank you.

Thank you for sharing such a humbling comment. In love, in pain, and in solidarity, we’re all navigating life together.

Every woman I know is a storyteller. Every woman I know is a camera.

It is through these women’s eyes and memories that we thread together what is left when the dust settles. Audre Lorde says “without community there is no liberation”.

Steadfast in conviction, these women heal eachother and their communities. They raise up martyrs and artists and countrymen. “سَنّد” in Arabic can mean support/ crutch, to hold up, but it also can mean contract or deed. Our woman are both the support and the keepers of the deed.

Beautiful work Sabah 🤍

Beautifully said, thank you ❤️🙏🏼