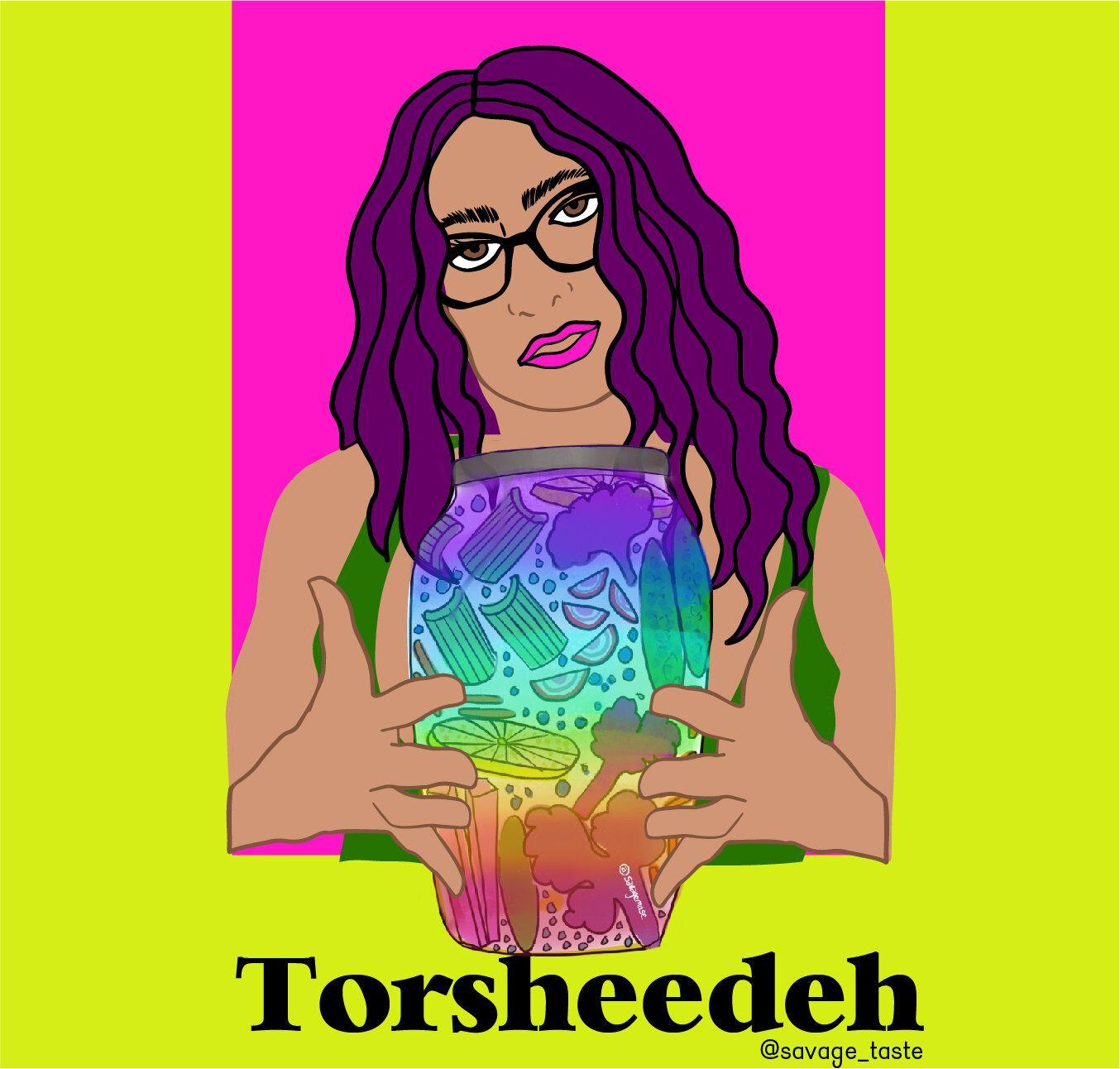

Parisa Parnian/Savage Muse

It’s funny being a 40-something queer Iranian-American woman in LA. My work as a visual artist and culinary creative centers so much around helping people tap into their desires, to find a sense of belonging, and in building intersectional communities, yet I myself have managed to stay solidly single for the majority of my adult life.

I had the distinct honor of being called “torsheedeh” quite early in my life, while standing in the pickled vegetable and jam aisle at a tiny Iranian market in Arizona.

Torsheedeh comes from the Persian word torsh, which in Farsi means “sour,” as in “the milk has soured” but also torshi, which means “pickled.” It is a term used in the Iranian community to describe single women who were considered past their prime and could be viewed with both pity and distaste. Once a woman was given that title, she was no longer desirable or considered potential wife material.

Around the time I was in high school, in the late ’80’s, there was a sudden influx of Iranians pouring into the desert town of Scottsdale, AZ. — a suburb full of cookie-cutter Spanish-tiled McMansions, retired “snowbirds” and Waspy golf resorts.

My immigrant Iranian family had called Scottsdale home since we landed there in 1976, when I was just four years old. Why my highly educated and sophisticated parents, who were both architects, chose to settle in a city where the locals were predominantly white, conservative and ignorantly hostile towards foreigners is another story. Suffice it to say that I was elated when other Iranians finally began settling in my hometown.

By 1988, I started hearing Farsi being spoken in the hallways of my high school — that is, before one of our math teachers, who always wore a cowboy hat and bolo tie, yelled at us for speaking the Persian language. He forbade us from speaking anything but English in the hallways from then on.

Still, I felt a tremendous sense of relief that I didn’t have to carry the burden of being the only one called an “Irayneeyun Terrorist” by bullies, and a sense of comradery knowing I would have other kids to eat lunch with who also brought leftover, pungent smelling Persian khoresht stews and rice to school in empty Mountain View yogurt containers.

Mountain View, an American brand of yogurt, appeared in supermarkets at some point in the ’80’s and I remember how excited my parents were when they discovered it had the same tangy, sour taste that Iranians enjoy in their yogurt back home. Unlike Americans, who preferred their yogurt sweet and even with fruit fillings in it, Iranians love their yogurt very tart and sour, to be served on top of steaming mountains of basmati rice or drunk as the beloved sour and salty carbonated yogurt drink called doogh.

As the Iranian community grew, so did the need for cultural resources. Slowly but surely, the Persian specialty food markets and kabob restaurants started sprouting, as well as the monthly Persian “discos” that I began frequenting at the local Hilton ballroom.

There were of course, also the lavish weekend dinner parties, where the men had a chance to have heated political and religious debates about the Ayatollah and Bush and all the conspiracies of The West, while the women, dressed in their glamorous sequined evening attire, clutching their designer handbags, shared their latest bargain fashion shopping triumphs and food market discoveries.

Clueless as I was at 17, both about my queerness and the social traditions of my Persian ancestors, I did not realize these dinner parties were also an occasion for the elders to scope out marriage prospects for their children. It turned out that the piercing feline gazes older Persian women were giving me at these dinner parties were actually the eyes of scrutiny to assess whether I was worthy of their sons, who were off at university becoming doctors and engineers.

By the time I was 20, it was clear to me that I was not destined for the traditional route of a semi-arranged marriage to a nice thirty-something engineer who came from a “good family.” Still living at home and getting my practical business degree from the local university, I was pining, not for a husband, but for the day I could escape to New York City and become an avant-garde fashion designer like Jean Paul Gaultier or Vivienne Westwood.

I knew there was something “different” about me, but had yet to discover what exactly it was. All I knew was that I often made Iranian parents uneasy when I was around them. Something about the way I carried myself and the way I spoke felt threatening and transgressive and unladylike, despite my outwardly feminine appearance. Today we would call that “big dick energy,” or just being a queer woman.

I had not yet fallen in love with my first boy (a Sephardic Jewish classmate from Mexico City who would reject me for not being Jewish), or my first girl (an Iranian British classmate who would be the first person I would get romantically involved with, and who would break my heart).

One day when I was still living at home, my mom asked me to pick up some dried herbs, barberries and pickled vegetables aka torshi from the local Persian market. I was excited to run that errand for her because as far back as I can remember, I have always loved going to food markets and grocery stores. It doesn’t matter if it is a basic American grocery store, a Costco or a specialty international food market, I am always curious to go and explore.

It turned out that I was going to learn more than I expected on my visit to the local Persian market. The shop owner was a traditional Iranian man who knew our family and had daughters around the same age as me. I had heard rumors that his eldest daughter was already engaged to an out-of-town doctor who drove a European sports car.

As is customary, he asked how my family was doing. He then followed me around as I walked through the narrow aisles of the tiny shop, crammed with glass jars of fruit preserves and pickled vegetables, burlap bags of basmati rice and plastic bags full of dried herbs.

He continued to ask me prying questions about my status as a single woman: “Khaastegaar paydaa kardee belakhareh?” which basically means, “Have you finally found any suitors; are you engaged?”

In traditional Iranian culture of that era, it was customary to get engaged to a man before you even started dating. Once you were engaged, you could go on dates with him without it causing a social scandal, although often you were still required to have a chaperone to ensure your virginity would stay intact until the wedding night.

I impatiently and with pride told him “NO!” and that I had big plans for my life and was planning to move to New York and become a famous fashion designer and had no interest in a husband at the moment.

The limits of my impatience were being tested, because even though I was only 19, Iranian elders constantly asked me if I had any suitors. I would tell them all the same things and would usually get met with a judgmental glare.

This time, however, I did not receive a silent reproach when I smugly replied that I was not engaged. Perhaps because for his own daughters, finding a financially secure husband was the most important thing they could do with their lives, my response sounded foolish and arrogant to him.

So with the distinctly Persian way of insulting someone while you have the sweetest smile on your face, he told me that with my attitude, I was certain to end up a lonely old woman and that I was well on my way to becoming torsheedeh.

Perhaps I should have been offended or angry that I was already considered torsheedeh in the eyes of some members of the Iranian community. But instead, when this shop owner insisted I was soon to be sour milk or pickled like the vegetables displayed on the shelf behind me, I felt a bit giddy inside.

To me being viewed as pickled or sour by traditional patriarchal standards meant I was allowed to live my life outside of the confines or expectations of a rigid society. It meant that just like the way a jar full of colorful vegetables floating in a vinegary brine develops a richer and more delicious flavor as the weeks and months go by, I too was free to develop a more rich and layered life with the passing of time.

Looking back to the first time I was called torsheedeh almost 30 years ago and assessing where my life has taken me to date, I can tell you with assurance that being called a “sour” woman at such an early age has only enhanced the sweetness and freedom of the life I have and am living.

Although as of this writing I am still a single woman in my forties, I am now ready to be savored like torshi seer, the black pickled garlic of the northern regions of Iran, where my mother and grandmother are from. This highly prized garlic becomes dark and sweet and mouth wateringly delicious with the passing of time, losing all of its bitterness and bite.

To all of you out there who have been made to feel that you are past your prime, I encourage you to change the narrative and embrace all the sour and pickled parts of yourselves and reclaim them as some of your most delicious bits.