Sepideh Gholian’s The Evin Prison Bakers’ Club is no ordinary prison memoir [but] a literary act of bearing witness, reminding us that freedom is not always a place — it is a state of mind, carried even through the thickest walls of confinement.

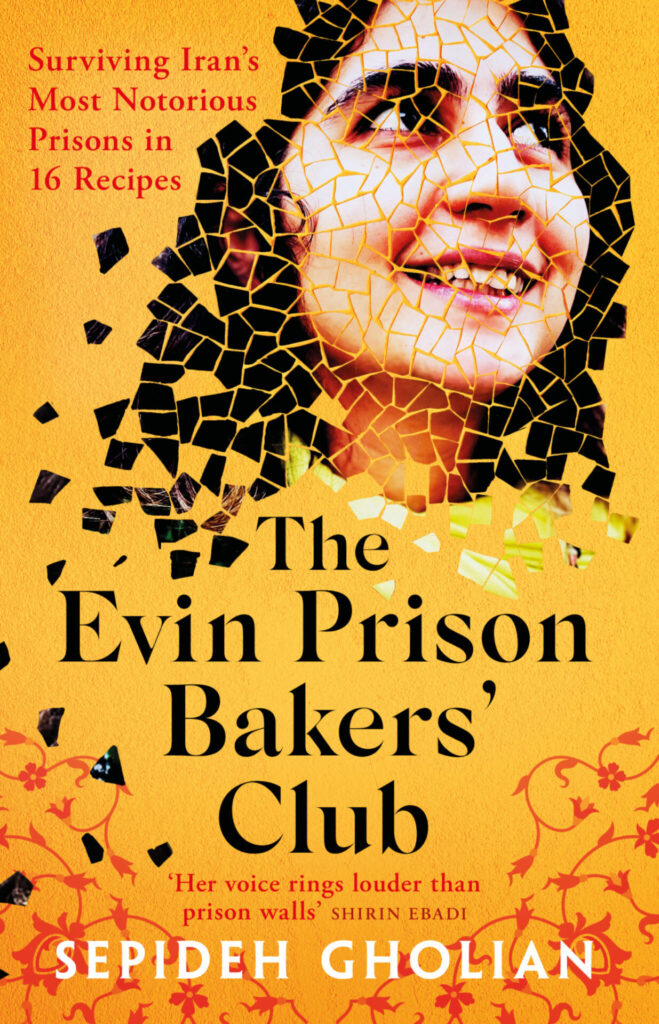

The Evin Prison Bakers’ Club, biography/memoir by Sepideh Gholian

Oneworld 2025

ISBN 9781836430308

Hannah Kaviani

There’s no doubt that what Sepideh Gholian delivers is a true page-turner. The harrowing account of an abortion carried out by an inmate in a bathroom corner — just out of sight of CCTV cameras — reveals this prison diary as a raw, unfiltered glimpse into the hidden realities behind prison walls.

The Evin Prison Bakers’ Club, originally published in Persian, is a book that easily absorbs the reader’s attention and sense of time. It covers events leading up to 2022 — the year the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement erupted in Iran following the tragic death of Mahsa Jina Amini in police custody. This movement is not an isolated event, but rather part of a continuum of resistance that has been unfolding in Iran for decades. Sepideh Gholian’s book stands as a powerful testament to this enduring struggle.

The prisoner begins with a candid confession: “I have never been a writer,” she admits, adding, “I doubt I’ll ever be one.” Yet in her second book, The Evin Prison Bakers’ Club, she captivates, shocks, saddens, and delights. This is no ordinary prison memoir. It resists the heavy-handed solemnity often expected of the genre and instead becomes a literary act of bearing witness — chronicling both injustice and life itself, while breaking beyond the conventional confines of prison literature.

For decades in Iran’s contemporary history, most prison memoirs — or literature related to imprisonment — have been written or published only after the prisoner’s release. But in recent years, that pattern has shifted. Thanks to the courage of prisoners, the support of their families, and the power of technology, more work is emerging from within prison walls. Sometimes — as in this case — a number of chapters were received via text or photos showing scraps of paper. However, the exact methods used remain undisclosed for security reasons. Another recent example is White Torture by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Narges Mohammadi, a compilation of interviews with fellow female political prisoners about the systematic psychological abuse in Iranian prisons. (Mohammadi, born in 1972 in Zanjan, Iran, is serving a 13-year and nine-month sentence on charges that stem from her human rights work. She was released from Evin prison on December 4, 2024, after authorities suspended her prison sentence for 21 days.)

Rarely has a literary narrative escaped from within Evin Prison with the force and clarity of Gholian’s work. With biting wit, relentless creativity, and the unbroken spirit of an activist, she paints an intimate portrait of life among incarcerated women — not only political prisoners like herself, but also so-called “ordinary” inmates, imprisoned for non-political reasons yet subjected to the same systemic injustices.

Sepideh Gholian is not your ordinary human rights activist in Iran. With piercing eyes, a calm smile, and hair that shifts from black to shades of blue or red, Sepideh doesn’t resemble the typical image of a civil rights activist in southern Iran. In a deeply patriarchal society, it isn’t just her appearance that stands out — her outspoken voice also distinguishes her from many of her peers. And although studying to become a vet, she is an aspiring artist, who utilizes artistic expression for advocacy and awareness raising.

Sepideh Gholian’s journey began in southern Iran, where she first spoke out for workers’ and minority rights — a voice that never ceased to challenge injustice, even from behind bars. Emerging from the banks of the Dez River and raised in a male-dominated society, her voice was initially heard online, and soon after, in the widespread labor protests across the region, including the 2018 strikes at the Haft Tappeh Sugarcane Company. One of her earliest arrests occurred while she was covering these protests as a citizen journalist.

She was 24 at the time.

Though written during her incarceration at Evin Prison in Tehran, Sepideh Gholian’s book recounts many of the harrowing experiences in prisons in southern Iran, particularly in Ahvaz and Bushehr. While Evin is internationally recognized as a notorious political prison, the contrast with these lesser-known facilities is stark. In the southern prisons, isolation, neglect, and severely limited access to necessities — compounded by the social pressures faced by women from traditional communities — create an even more punishing environment. Gholian has previously published a book focusing on Arab minority women in prison, and many of their stories reappear in this new work, woven into a broader narrative of resilience and resistance.

Although Sepideh Gholian is not Arab — her family is ethnically Lur, from the nomadic Bakhtiari tribe — being born and raised in Khuzestan has given her a deep understanding of the discrimination faced by the Sunni Arab minority in Iran’s oil-rich southern region. Systematic marginalization, state neglect, and harsh living conditions have made civil rights activism in such areas particularly dangerous and costly. Gholian was deemed such a security threat that authorities transferred her to Tehran, choosing to detain her among other political prisoners in Evin. Yet throughout her book, she pays tribute to her fellow Arab inmates — not only by recounting their stories and the severe injustices they faced inside and outside prison walls, but also by giving voice to their cultural heritage. She weaves their language, legends, and traditions into the narrative: recalling the pain of a woman named Deyhengo, she notes that “Dey” means “mother” in the Bushehri dialect; in another passage, she describes an inmate longing for finger-twist halva, a regional confection, evoking memory and identity through taste.

Until 2022, Sepideh Gholian had been arrested multiple times, subjected to torture, and coerced into delivering televised confessions against herself. Despite this relentless repression, she refused to remain silent. Then, in the winter of 2023, upon her release from Evin Prison, she emerged wearing the traditional dress of Balochi women — another ethnic group in Iran long subjected to systemic discrimination. Standing defiantly, she shouted a slogan condemning the Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, likening him to Zahhak — the legendary tyrant king with serpents growing from his shoulders — declaring that the people would one day overthrow him. Within hours, as the video of her bold act went viral, she was arrested once again. Gholian has already served two years for “insulting the Supreme Leader” and is currently serving another 15-month sentence for accusing a state TV journalist of collaborating with intelligence agencies.

The Evin Prison Bakers’ Club presents itself as deeply personal, yet it resonates on a universal level. It is not merely a book of suffering; it is, ultimately, a celebration of resilience. Amid heavy themes, the book also features simple but meaningful recipes — culinary expressions that offer moments of solace and human connection. Like the writing itself, Gholian stays humble about baking too and says:

You might well ask, Isn’t prison … prison? How the hell could you be making confectionery there? And you would be correct. But if baking badly is an inalienable part of who you are, then you can do it anytime, anywhere, and — yes — in any kind of prison. Even without gas.

Following the model of Evin, while incarcerated in Bushehr Prison, Sepideh Gholian established a kitchen, attempting to bring a spark of life to the dark days of fellow inmates. But even this modest act of hope was not tolerated, as it created a communal space that authorities deemed a violation of “red lines.” The situation is different in Evin Prison, in the northern part of Tehran, where inmates have access to cooking facilities, libraries, and workshops, some of which have been expanded or established by the prisoners themselves. Addressing the attempts to expand possibilities at Evin, Gholian compares baking utensils with “weapons of choice,” adding, “They were plainly not going to release us so we were going to get a tart tin out of them, at least.”

As if inviting the reader to imagine making the recipes in confinement weren’t intimate enough, Sepideh Gholian goes a step further, pairing most recipes with music recommendations. She encourages readers to listen to specific songs while whisking eggs or stirring ingredients, transforming a simple act of cooking into a ritual of reflection and resistance. Some of these songs are protest anthems that Gholian and fellow inmates at Evin Prison sang repeatedly during their incarceration — songs whose echoes have even traveled through the prison’s scratchy phone lines.

Sepideh Gholian’s attempt to deliver a “literature of witness” is evident on every page of The Evin Prison Bakers’ Club. It’s not just in the stories of the women she writes about, but also in the vivid, often haunting details of the prison itself. From the chairs in the interrogation rooms to the tiles on the corridors — the very tiles that might be the only thing an inmate sees while being escorted to those rooms — Gholian calls upon all of the human senses to bring the experience of imprisonment to life. Although her style of writing and diction seem unsophisticated and simple at times, she doesn’t just tell the story, but makes one feel it, such that every moment and detail resonates deeply with the reader.

There is a sharp contrast in the way the phrase “let’s move on”— or “Begzareem” in Persian — is used throughout the book. Typically, this phrase is employed in conversation or when retelling events, rather than in written form. However, in The Evin Prison Bakers’ Club, as Sepideh Gholian attempts to “move on” to the next chapter, the next story, or the next person, she consistently reminds us not to forget. This subtle yet powerful repetition serves as a call to remember the lives, struggles, and voices that might otherwise be lost in the transition from one moment to the next.

Although written before the rise of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, the spirit of its slogan pulses through every page of Sepideh Gholian’s work. She draws no line between prisoners — every inmate, every woman, regardless of her status, is given voice, dignity, and the undeniable right to exist.

In stark contrast to the divisive political climate in Iran, Gholian refuses the common categorization of “ordinary” versus “political” prisoners. To her, the lives and stories of all prisoners matter. Even those who have died in silence deserve remembrance and honor.

In The Evin Prison Bakers’ Club, “life” is not just endured — it is celebrated, even in the darkest of dungeons and most desperate moments. With minimal ingredients, women bake cakes. With scraps of fabric and light, they stage shadow plays. These acts, small as they may seem, are quiet rebellions, affirmations of life against a backdrop of repression.

Recent backlash against political prisoners — especially when they are seen dancing, smiling, or wearing makeup upon release — highlights a troubling mindset: that expressions of joy and vitality undermine the seriousness of activism. But for Gholian, and for many like her, every step toward joy is itself a radical act. Choosing life is part of the struggle.

The third word in the slogan, Freedom, may seem ironic in the context of prison. Yet, even behind bars, the freedom of thought, the power of imagination, and the will to resist remain alive. Gholian’s writing reminds us that freedom is not always a place — it is a state of mind, carried even through the thickest walls of confinement.