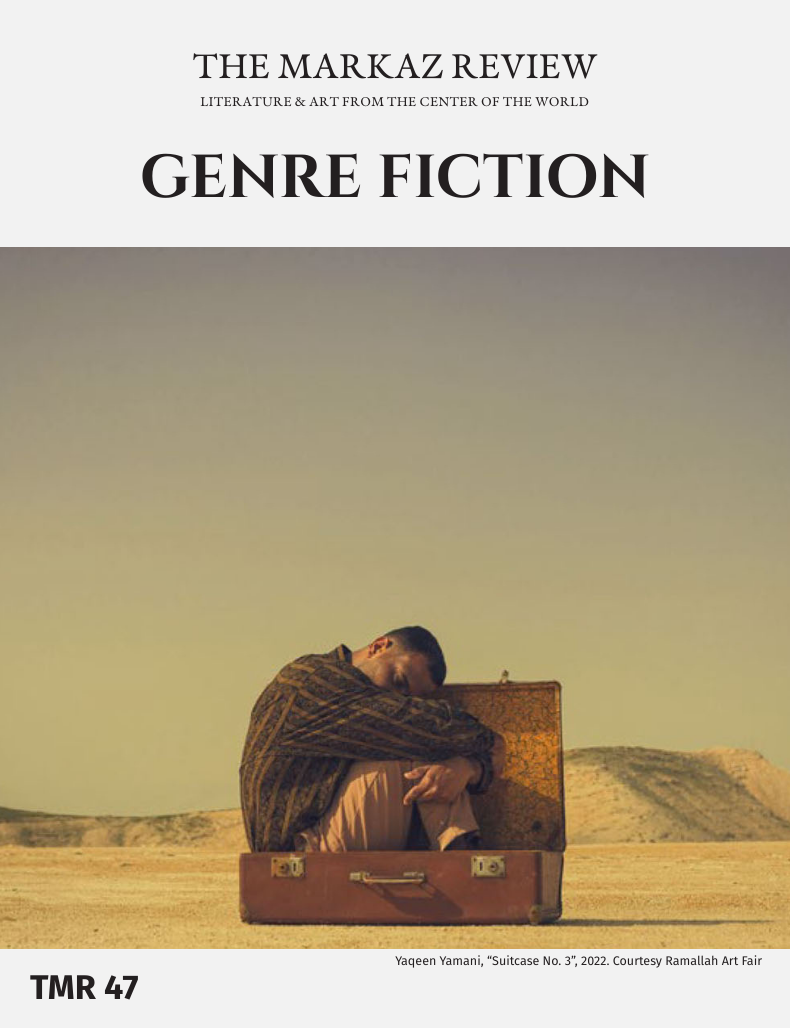

In which our literary editor becomes your guide through TMR 47, a double issue packed with fiction and the last monthly issue of 2024.

Some of the earliest forms of genre writing that appeared in Egypt in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were utopian in scope. Although Egypt traditionally led the way with new norms in regional literature, this fresh burst of ideas had been brought on by unrest in the wider Middle East. Syrian and Lebanese writers fleeing religious and political persecution, writes Amr Aboelsoud drawing on the literary criticism of Saad ElKhadem, settled in Cairo and experimented “with the novel and other genres that were previously unknown in the Arab world. They … took up themes and motifs that were still untouched, such as free love, adultery, and the emancipation of women. With these ‘romances’ they attracted more readers and diverted them from the traditional literary genres. Nevertheless, both the traditional reservoir of themes, motifs, and styles as well as the new, adopted themes, and forms contributed to the development of Arabic literature in the direction of modernity.”

Today popular forms of genre fiction encompass romance, horror, suspense, and speculative writing, with the latter including sci-fi and fantasy, and further sub-categories of alternative history and time travel. Is the graphic novel genre fiction as well? For many, genre fiction is escapism pure and simple. But can the form hint at solutions, and suggest a possible way out? Through the mechanisms of reading and dreaming, surely an individual has the possibility of stealing themselves to harsh realities. The writing may be varied, but in the end it comes down to the power of storytelling.

From Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon to Iraq and Afghanistan, forms of genre fiction morph. They hold a certain power because of how writers, whether in the region or the diaspora, reflect and often react against the social mores and political settings. This special double issue of The Markaz Review closes the turbulent year of 2024, and suggests critical green shoots for starting afresh in 2025. Alongside wide ranging short stories, excerpts from novels, and new English translations are critical essays on politics and art, some of which feature artists who dare to go to the moon. In many ways all of the work included here are visions of our tiny planet at a time when ongoing war in the region has left many scared, angry, and depressed.

Love, love, love

The mission statement for Harlequin, one of the most popular publishers of romance fiction in the US — “Emotion and intimacy simmer … experience the rush of falling in love” — only begins to capture the range of feelings and experiences in the romantic stories included in TMR 47.

The issue’s centerpiece fiction is “Not a Picture, a Precise Kick,” from Mansoura Ez-Eldin’s novel Akhyilat Athill [Shadow Specters] (2017), translated from the Arabic by Ibrahim Fawzy and Fatima ElKalay. After visiting Kafka’s House, in Prague, a man and a woman meet on a park bench. Both are writers but the woman is in a daze. Newly arrived from Cairo, she realizes that she has been walking around places in a foreign city that she recognizes from her dreams. At home, Camelia has endured an eventful love affair and unwanted pregnancy. Ez-Eldin’s Akhyilat Athil is a meta novel that considers the nature of writing, gender, and identity.

The next story, Huda Hamed’s “Envy,” translated from the Arabic by Zia Ahmed, is again about the failure of romance. But the two people in intimate conversation, the soon-to-be divorced daughter and her mother, dissect an ailing marriage not from inside but from the view outside. How can a dissolution like this be justified to an extended network of family and friends? In deeply conservative cultures when marriages fail, there should be a dramatic, no-turning-back story to tell, which enables a wife to save face and lessen her family’s disgrace. Surely an argument over the Persian rug isn’t enough justification on its own. Yet, mother and daughter come to an understanding. Hamed is one of Oman’s best-known women writers. She tells unusually nuanced stories that shed light on not widely known female experiences, like her young Besara woman’s coming of age story, published in TMR 43.

Continuing on the theme of romance, a tale of thoroughly modern queer love takes its title “As Much of Life As the World Can Show” from a quote by Samuel Johnson about 18th-century London. In an excerpt from Fil Inocencio Jr.’s first novel of the same name, a chance encounter, fevered SMS messages, and international travel brings together one man from the West coast of the US, and another from Amman, Jordan. They meet in gay Arab London, a setting rarely written about in mainstream fiction.

The protagonist here, in love, hasn’t forgotten the trauma of non-acceptance in his own life and reminds his lover’s Arab friends of theirs, as he makes a case for those badly maligned and targeted in Trump’s America — the trans community.

These are storylines that won’t be found in run of the mill western romances. But love in the Middle East has many opposites that seemingly coexist and intertwine; they can be both stifling and liberating; full of wonder yet filled with immense disappointment; not entirely inclusive for now, but multi-faceted with the underlining hope they might become so.

Fright show

Horror is another hugely popular form of genre fiction, and in this issue of TMR, these types of stories too take on telling cultural specificities. Natasha Tynes is from a Jordanian family. For her scary gastronomic short story, “The Head of the Table,” she draws on her father’s reminisces of eating the traditional meal of mansaf, made with lamb, rice and pine nuts.

The power of horror, it seems, lies in the upending of the familiar, or injecting fear into the perfectly innocent — even nature. The chinar tree (Platanus Orientalis), originally from Greece, is known as the “Tree of Hippocrates” due to its medicinal properties. Fourteenth century Islamic preachers journeying from Iran to Kashmir brought its seeds to Afghanistan.

The short story “The Curse of the Chinar Tree,” by Shamsia was translated from Dari by Abdul Bacet Khurram. The ailing health of a chinar tree outside a family home in rural Afghanistan mirrors the sickness growing inside, as a malevolent, shiny black stone possesses the family’s patriarch. All the ingredients of obsession are in play: the tensions between religion and madness; frightened children, and an unspoken threat of ever looming violence.

Disappearing detectives

Not all forms of genre have remained popular throughout the decades. Regional gumshoes from Cairo to Tunis were once modeled after Western favorites Sherlock Homes and the private detectives in Agatha Christie novels. However this has changed as editor of ArabLit, Marcia Lynx Qualey, reveals in “Salacious Criminality — Trench-coated Detectives, Rogues, and Smoking Guns,” a specially commissioned essay for TMR 47.

One reason for the decline has been the nature of governance in the region. Qualey writes, “… toward the end of the 20th century, traditional police and detective novels lost much of their glamor. One reason might be the way the genre can take the side of police and repressive state institutions. Toward the end of the 20th and early 21st centuries, readers were more likely to find prison novels in Arabic than police procedurals, as many serious novelists seemed more interested in humanizing prisoners than allying themselves with jailers.”

Fly me to the moon. Or at least around the Earth

As sleuthing in literature became less prevalent, sci-fi never lost its appeal for writers and artists in the Middle East and beyond.

Elizabeth Rauh’s “Traveling Crafts: The Moon and Science Fiction in Modern and Contemporary Middle Eastern Art” was first published for the Aga Khan exhibition, The Moon: A Voyage through Time (2019). Guest curated by Christiane Gruber with curator Ulrike Al-Khamis, the exhibition was the first to explore the centrality of the moon in Islamic faith, science, and arts, in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the Apollo 11’s historic moon landing when Neil Armstrong made that “giant leap for mankind.”

“Speculative narratives, otherwise known as science fiction or the ‘literature of ideas,’” Rauh writes, “offer projected re-imaginings of human experience by depicting new or imaginary technologies, time and space travel, alien beings, and utopian or dystopian worlds. Besides literary works, science fiction offers artists visual tools to imagine — or reimagine — the world as it was, is, or will be.”

The many artists who fell under the spell of Earth’s little sister range from Sudanese artist Ibrahim Saleh and the founder of Iraqi modernism Jewad Selim (1919–1961) to Lebanese artists Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige. Their film, The Lebanese Rocket Society (2012) revives forgotten history. In the early 1960s, a pan-Arab project with scientists and technicians from Armenia, Iraq, Jordan, Jerusalem, Palestine, Syria and Lebanon produced the first rockets from the Arab world. These traveled to Low Earth Orbit — an altitude of 1,200 miles or less, within a period of 28 minutes.

The featured artist for TMR’s special double issue is Larrisa Sansour, who appears as an astronaut in her video A Space Exodus. Sansour, known for subverting easily recognizable Western pop culture, music and film in her work, soars above the Earth accompanied by a Middle Eastern-ized version of Richard Strauss’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra. This was the original soundtrack to Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001, from which Sansour takes her inspiration and imitates — except for her final destination. This astronaut artist is not headed towards a black monolith past Jupiter, but Earth’s moon, where she plants the flag of Palestine.

Following Sansour into deep space is May Haddad’s intergalactic girl-messenger Carna. In the tradition of Star Wars, “A Galaxy Run in 30 Minutes Or Less” is the prequel to an earlier story of Haddad’s, “Ride on, Shooting Star,” which appeared TMR in 2022.

The best sci-fi borrows heavily from other genres as well. Published in Egypt in 1972, Qahir al-Zaman [The Conqueror of Time] by Nihad Sharif is considered one of the earliest sci-fi novels written in Arabic. On reading the first ever excerpt from the novel translated into English by TMR senior editor Lina Mounzer, our editor in chief Jordan Elgrably described it as “quite creepy and fascinating” because of its “air of reality.”

In the novel, Dr. Halim, who is intent on unlocking the secrets of cryopreservation, keeps a diary. The novel’s protagonist and the reader are pulled in by entries like this one: “And as I poured the water out of the cold glass, an idea struck me… The refrigerator cools meat of any kind to keep it from spoiling. And refrigerated meat of course consists of the flesh of dead or slaughtered animals. Would it one day be possible to use it to preserve a living body? The question opened up new horizons before me …”

Qahir al-Zaman, written by Sharif during the last years of Gamal Abdel Nasser’s rule, is thought to be political allegory. Dr. Halim’s cryogenic experiments on small mammals is a metaphor for Egyptian society “as stagnant, figuratively frozen in its obsession with the past,” according to Ian Campbell in his book Arabic Science-fiction, from 2018.

Activating history

In cities like Cairo the past lives on in streets, gates and quarters that still bear the names given to them in medieval times. Walking through these and writing about them are akin to time travel. Like the moon, effortless, inexplicable sudden jerks through time backwards and forwards have long fascinated Arab writers. According the translator and writer Michael Cooperson, the first time-traveling novel in Arabic is Hadith Isa bin Hisham, [A Period in Time] by Muhammad al-Muwaylihi (1858-1930). Cooperson is also the translator of Khairy Shalaby’s novel, The Time-travels of the Man Who Sold Pickles and Sweets (2016), an excerpt of which has been included in this issue, under the title, “The Man with the Samsonite Briefcase in Medieval Cairo.”

Khairy Shalaby named the main character, Ibn Shalibi, after himself. His novel is one architect and historian Nasser Rabat considers in his new book Writing Egypt: Al-Maqrizi and His Historical Project. He writes, “Ibn Shalabi’s obsession with a spatially and historically confined past (Fatimid, Ayyubid, but mostly Mamluk), however, has an underlying motive. His time travel is actually a rescue mission. Its deeper intention is to conscript the entire Egyptian Islamic history in order to recuperate the authentic Egyptian national character.”

Ibn Shalabi meets not only Arab historians Ibn ‘Abd al-Hakam (803–71), Ibn Taghri-Birdi (1411–70), and the Orientalist Stanley Lane-Poole (1854–1931) but the Egyptian Nobel Prize winner in Literature, Naguib Mahfouz (1911–2006). However it is the Mamluk historian and biographer al-Maqrizi who makes repeated appearances in the novel. As Nasser observes, he “has been lodged in modern Egyptian consciousness as the true keeper of Cairo’s history across the ages.”

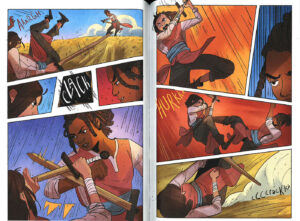

Another city that looms large in the Arab consciousness is Beirut. The euphonious graphic novel by Barrack Zailaa Rima, translated into English by Carla Calargé and Alexandra Gueydan-Turek, also from earlier this year, contains a trilogy of comics all on Beirut, from 1995, 2015, and 2017.

In her review of Beirut, TMR critic Katie Logan delves into the question of boundaries between graphic novel and genre fiction: “Reviewing Beirut for an issue on genre is especially fitting, with an important caveat. As comics theorists assert often and with force, comics and graphic novels are not in themselves a genre …What makes comics such a compelling art form is the way they adapt and contort to contain a host of genres. Inside the graphic novel are unlimited possibilities for narrative structure and graphic representation, possibilities Rima exercises with visible abandon throughout Beirut.”

Speculations

Like sci-fi, fantasy is another form of speculative fiction. Instead of defying the laws of nature and physics, it offers instead the improbable. The cyber-punk story “Ghosts of Farsis” by Hussein Fawzy, translated into English by TMR’s managing editor Rana Asfour, includes as one of its characters a learned, talking duck.

Perhaps more unlikely than a loquacious bird is the main character of Adam’s much-maligned wife in Parand’s short story “Eve,” translated from Afghan Dari by Abdul Bacet Khurram. Eve has had enough of being blamed for original sin and decides to leave Purgatory. She doesn’t go to Paris or New York but to Kabul, where she not only watches the fate of the homeless woman holding a dead baby, but becomes her. Both Afghan women writing for TMR 47, Parand and Shamsia, the author of “The Chinar Tree,” are members of the development Untold Narratives project that works with “writers marginalized by conflict.”

In the issue, “The Small Clay Plate,” a cautionary tale about greed by Bel Parker, conveys an even more exaggerated fable-like quality about it. The theatre director was told this story, sitting around the campfire in Siwa, on the edge of the Sahara desert. She said she tried to translate it to the best of her abilities, but wondered in hindsight if she had inadvertently added embellishments or details of her own. Parker wrote “The Butcher’s Assistant,” about her experiences in Alexandria, for TMR’s double literary issue in the summer.

The two weird fantasy short stories by Iraqi writer in exile Azher Jirjees — “Orient Tavern” and “The Hungarian Hut,” both translated from the Arabic by Yasmin Hanooch — also have a strange out of time quality to them. In “Orient Tavern,” a dead man walking is unaware of his death in the aftermath of a sectarian attack. While “The Hungarian Hut” reveals the vulnerability and trauma of illegal migrants. Victims to anyone, as Jirjees puts it, they might as well be dwarfs, steeped in donkey urine.

The fiction in the issue closes with an excerpt by Radhika “Ra” Singh from Weirdly Tuned Antennae, a novel in progress of speculative fiction set in a post-imperialist future. These words resonate: “Between ruler and subject a mutual contempt and fear. The colonizer suspended between smoke and mirrors, terrified of discovery, clinging to a throne built on stolen ground, stolen labor, as proof of its relevance. Terrorizing a people that can see through the illusion, that study it to understand how the game is rigged, that question why they’re the ones begging for a ‘seat at the table’ when the table never belonged to them, you said. It always belonged to us.”

From fantasy back to grim reality

One can’t think of the end of this year without acknowledging the utter brutality of the war against Gaza, and the continuing starvation of its people. At the time of writing yesterday morning, the news broke that Amnesty International’s latest report concludes that the “atrocity crimes” against Israelis by Hamas on October 7, 2024, cannot be a justification for the genocide and “hell” the IDF has unleashed on Gaza’s 2.3 million people. This is after yet again another bombing by the Israeli Air Force, with weapons paid for by the American taxpayer, of Palestinians sheltering in a so-called “safe zone.”

On November 28, the Oxford Union debated the question “This House believes Israel is an apartheid state responsible for genocide.” Novelist Susan Abulhawa makes a persuasive case. She says in the speech, the full text included in TMR 47, that she has come in the spirit of staunch anti-colonialists, anti-imperialists, and anti-Zionists Malcolm X and James Baldwin.

She is also there, “For the sake of history. To speak to generations not yet born and for the chronicles of this extraordinary time where carpet-bombing of the defenseless indigenous societies is legitimized. I am also here for my grandmothers, both of whom died as penniless refugees while foreign Jews lived in their stolen homes.” The motion at the Oxford Union was passed overwhelmingly by 278 to 59 votes.

As this unjust war rages, TMR continues to provide a platform for Arab and other Western Asian or North African voices, art, and stories. First and foremost it is an advocate for Palestinian rights.

Genre fiction flourishes when the planets aren’t aligned and the world has turned to shit.