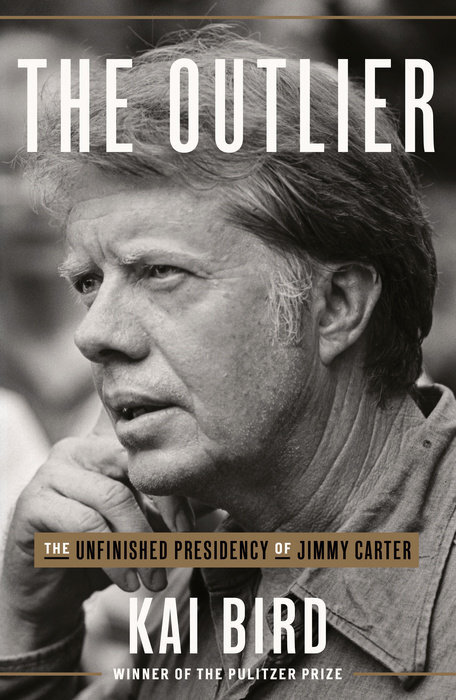

The Outlier: The Unfinished Presidency of Jimmy Carter A biography by Kai Bird Penguin Random House (June 2021) ISBN9780451495235

Maryam Zar

The Outlier is published by Penguin Random House.

Before the end of Inauguration Day on January 20, 1977, newly-sworn-in President Jimmy Carter made his first executive decision — one that would prove controversial like many more. He appointed his head of Veterans Affairs, Max Cleland, then swiftly asked him to support what would be an Executive Order to pardon all Vietnam draft dodgers. Cleland warned, “…there is growing opposition among members of the Senate to your plan to grant amnesty to draft dodgers.” Carter briskly retorted, “I don’t care if all 100 of them are against me. It’s the right thing to do.” Thus the tone is set for his entire “unfinished” presidency, as Kai Bird describes it in his new book, The Outlier. Bird accompanies the reader through a domestic history of the United States, focused at first on the civil rights movement as it burgeoned and slowly seeped through the South, where a young James Earl (“Jimmy”) Carter came of age, and then advanced through the unexpected political career of the man who became an unexpected President. Heir to a peanut farm, Carter grew the business to what would be billions of dollars in value by today’s standards. With a natural combination of innovation stemming from an engineer’s mind and the charisma of a deft politician and a wily businessman’s sense of what sells and when to call a bluff, Carter navigated the Southern political landscape, then the national Democratic party inside track and finally, Washington, DC. Through it all, Kai Bird walks us through a lifetime that encountered some of the biggest issues of our time, and some of the most memorable characters in 20th century American political history — including Ruth Bader Ginsberg, whom Carter elevated to the Federal bench (and Clinton later appointed to the Supreme Court), Ed Koch, the colorful NY Mayor (paving the way for Rudy Giuliani), and Ted Kennedy, as Chappaquiddick swallowed his political future.

“Carter is perhaps our most enigmatic president. He is often celebrated for what he has achieved in his four-decade-long post-presidency. Conservatives and liberals alike accord him the accolade of “the best ex-president.” But most citizens and the punditocracy routinely label his a “failed” presidency, ostensibly because he failed to win reelection. But in truth, Carter is sometimes perceived as a failure simply because he refused to make us feel good about the country. He insisted on telling us what was wrong and what it would take to make things better. And for most Americans, it was easier to label the messenger a “failure” than to grapple with the hard problems. Ultimately, Carter was replaced by a sunny, more reassuring politician who simply promised that he would “make America great again.”

— Kai Bird

The chronicle begins in the Deep South of rural southern Georgia, at a time when white boys kept strictly white company and school segregation was a battle-line between friends. Jimmy, by conspicuous contrast, made lasting friendships with Black peers and supported desegregation. He learned the depth of kindness from his mother, Miss Lillian, and the Black families they befriended who forgave after great injustice was visited upon them in a “sadistic” South where tradition was justification for great violence. Later, united as a couple with southern belle Rosalynn Smith — his wife and political confidant now of 75 years — they supported desegregation unabashedly. The Carters lost friends over their refusal to support the enduring tradition of Southern segregation but stayed the course because they believed they were on the right side of history. History looms large for Carter, who grew up in a household (famously run by his flamboyant mother who became a media darling during his presidential years) that demanded literacy, taught righteousness, and ingrained a deep sense of service. Carter was raised — and saw his political fortunes rise unexpectedly — in post-bellum Georgia, where “a belief in white supremacy permeated the red baked clay.” But his consciousness diverged from Jim Crow’s well-trodden path, and he eventually understood that he was comfortable operating as an “outsider.” His first successful campaign (after a failed run) for Georgia governor would hinge on being able to present as the candidate with a healthy distance from the political establishment. After he won, his first statement would make him an outlier even to the anti-establishment supporters that propelled his win. He famously proclaimed in his 1971 acceptance speech at the gates of the Governor’s mansion that “the time for racial discrimination [in the South] is over!” His advisers would warn him not to alienate his allies and his opponents would charge him with having a “liberal heart.” But Carter remained undeterred, so that when he finally set his sights on the presidency, he did so knowing he would be the outlier candidate with an unlikely chance. When his campaign won a narrow victory against Gerald Ford, sweeping him into the White House, the new President owed nothing to anyone and had proven the critics wrong. That unique brand of populist politics masterminded by his shrewd team of Georgia’s youngest was a jolt to Washington politics. There they upended norms and ruffled feathers all the way to the Oval Office, to which Carter brought back the historic Resolute Desk (then on loan to the Smithsonian) and made cardigans and blue jeans acceptable attire for the world’s most powerful man. Their mission was to “depomp” the Presidency.

If power corrupted most, it humbled Jimmy Carter. He operated the executive branch with the authority given to him by the people, to do the right thing. Rarely considering consensus if it meant a trade-off of ideals, Carter always meant to keep the best interests of the American people at heart. This gained him no allies in Washington, where brokering for power is an art and outliers pay a price. Rosalynn once warned him that he would be doing the American people “no favors” if he couldn’t get re-elected. Her words proved prophetic as Carter’s Presidency wound on and the challenges mounted — both at home and abroad — with Carter surrounded by few Washington allies. Among his great ambitions was Middle East peace. Carter believed that a comprehensive peace which addressed the grievances of both Jews and Arabs was the right thing to work towards. He believed that a Southern man with Christian roots and the intellect to cut through posturing and unravel the impasse was just the persona to do it. This was a mission, not a political task for him. Carter set out to make peace with both sides, essentially by using himself and the credibility of the American presidency as a bridge. He reached out to Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, to befriend each. Thus began the road to Camp David and the historic peace accord that came with a shared Pulitzer Prize recognizing the effort; but a political fate that would see the assassination of one, the resignation of another and a failed re-election bid for the host. It seems the seeds for the post-presidential life of Jimmy Carter were probably sewn then, as Carter recognized no Israeli partner for peace in Begin but a warm and eager disposition in Sadat. In a 1977 phone conversation with James Callaghan, the British Prime Minister, Carter intimated that he was “favorably impressed with the Arab leaders,” believing “they genuinely want to make some progress [on Middle East peace].” His impression of Sadat, he confided to Rosalynn, was that he was akin to a “shining light” on the Middle East stage — “a man who would change history.” A year later, after several meetings with Begin, he would confide in his diary that he thought the Israeli Prime Minister was “a small man with limited vision [who] will not take necessary steps to bring peace to Israel.” To the extent that Arab-Israeli peace was a minefield he chose, the Iran debacle was one he walked into unwittingly. On New Year’s Eve, 1977, Rosalynn and Jimmy Carter were in Iran, graciously being hosted by Shah Reza Pahlavi and his wife, Empress Farah, at a “delightful banquet.” That evening, Carter would give a fateful speech that would be remembered by the words, “because of the great leadership of the Shah, [Iran] is an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world.” Months later, when the new regime of Ayatollah Khomeini came to power and held 72 American hostages for more than a year, bringing the Carter presidency to its knees, those words would haunt him. But Kai Bird reminds us that following that phrase, Carter went on to publicly deliver a thinly-veiled critique of the Shah. “[I]sland of stability would be quoted with mockery by the pundits,” Bird explains. “But never cited is the fact that Carter’s toast also included a pointed quote from the thirteenth-century Persian poet, Sa’adi: ‘If the misery of others leaves you indifferent and with no feeling of sorrow, then you cannot be called a human being.'” Carter had seen the protests not more than a few weeks earlier in November, when the Shah had visited the White House and Iranian students studying in America had formed loud demonstrations around the perimeter. DC Police responded with so much tear gas that when the air wafted over to the South lawn, the Shah could not avoid having to wipe away tears. Carter must have known in the back of his politically-astute mind that this monarch was in more trouble than anyone could tell, amid the festivities that permeated the pomp of a state visit.

At home, by February of 1978, the only national security aide with experience on Iran, Gary Sick, was warning Carter’s national security advisor, Zbignew Brzezinski (“Zbig”) that “the truly massive riots” now taking shape across Iran were not “communists,” but the “work of what may be the true threat to the Shah’s regime — the reactionary Muslim right wing which finds his modernization program too liberal and moving too fast away from the traditional values of Iranian society.” Zbig, for his part, “couldn’t imagine that the Shah couldn’t handle a few hundred rioters.” Months later, the Shah was a deposed monarch who fled his homeland, head bowed, flying around the globe in search of medical care. Carter had to decide whether he would risk US hostages to serve a dying king he had befriended, or refuse him permission to land Stateside. To many Iranians who had already fled Iran in fear of what a fierce revolution might bring, the king without a landing strip did not bode well. For families like mine here in the States, those were tense days we watched with great angst as they incredulously played out. What we thought was a staunch Iranian ally in Jimmy Carter turned out to be a vacillating President without the resolve to aid his friend, the Shah. That was, at least at the time, how many saw it. It would take decades for me to grow my own knowledge of the Carter presidency, the Pahlavi dynasty and the forces of populism to fully understand that the great conspiracy theories that would have the US totally responsible for the downfall of the Shah, or simple protests by the sons of conservative families masterminded the rise of a demagogue, were both misguided. Carter was a man who was motivated by an unyielding moral compass that wouldn’t compromise, and the populous masses in Iran weren’t chanting for an Islamic Republic but for change they couldn’t achieve through a fair political system that gave them a vote. The Shah fled on Carter’s watch and Iran fell into chaos — played out most visibly through the images of American hostages blindfolded and paraded before photographers and television cameras.

“Pundits wryly joked that Carter was the only ex-president to have used his presidency as a ‘stepping-stone’ to higher achievements.” — Kai Bird

The world blamed Carter. A daring rescue attempt failed dismally, cementing Carter’s legacy as shamefully incapable. With few allies at home or abroad, Carter watched the American national memory fade around his policy achievements and rise with collective ire around the hostage crisis. In the end, Carter refused a sickly king deposed by his people and negotiated the release of the hostages using quiet back channels that forged a deal with humiliating timing. Carter would lose the Presidency to a masterful communicator in Ronald Reagan, and cede his legacy as an effective leader in large part over what became an unmistakably complex crisis in a complicated region where Carter had culled very few allies. If foreign policy was not, in the end, among Carter’s enduring accomplishments, domestic wins should have cemented a kinder legacy for this one-term president. He established the Department of Education as we know it today, and set the stage for some of today’s progressive narratives around fundamental fairness and equity. Among them was his bold move to protect vast lands in the Alaskan wilderness from oil and gas exploration. In 1978, an Act that protected 80 million acres of wildlands was due to expire, risking 45 million of its protected acreage. Carter desperately wished to save it. A consummate environmentalist even then, he had written to the great photographer Ansel Adams saying he considered “the protection of Alaskan lands the top environmental issue of our time.” As the deadline loomed, Carter’s interior secretary suggested an untested move to use the 1906 Antiquities Act protecting “building and lands as national monuments” as a means to use unilateral power of the Executive to designate 56 million acres of Alaskan wilderness as a national monument, preserving it at least for the next two years. The gambit worked — but lost Carter more allies in the Alaskan political establishment. By then, he had already been defeated in national elections and was preparing to walk out of the Oval Office a lonely man. This book suggests he could take solace knowing he had done all the right things, as he saw them to be. The author has an unmistakable affinity for the subject as a man who was perhaps ahead of his time, or too altruistic for the role. With this book, Bird cements the likelihood that Carter’s ultimate legacy will not be his failed one-term presidency with foreign policy debacles crowned by a humiliating hostage crisis, but a well-intentioned man who ultimately proved the moral compass by which he governed to be an admirable one. Today, Carter’s legacy is still shaping — perhaps as an ever criticized US president with an anguished end to his single term in office — but Kai Bird makes the case for a principled President, who remains a proud man on the world stage and a hero for progressive humanitarians everywhere.