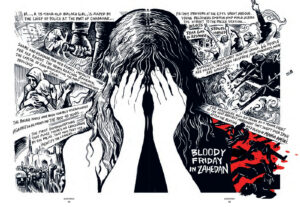

From artful outrage to raw facts and situations beyond comprehension, this new generation of Palestinian poster art revitalizes a tried and tested artform that brings to light hidden truths during war, civil strife and social struggle.

The war on Gaza has helped unite farflung artists, from the Occupied Territories and Lebanon to Mexico and China. Hundreds around the world have created posters in solidarity with the Palestinian cause. There is, in fact, a resurgence in posters as an art form for raising awareness. Many of these artists have organized campaigns and started initiatives to pressure the politicians in their respective countries to take action against Israeli apartheid against Palestinians, and war crimes committed by Israel in the Gaza Strip.

Artist collectives such as Art Commune, started by Palestinian artists to make artworks accessible and available for public use, have requested that artists worldwide contribute to global media platforms, as critical Palestinian voices in art and literature have been banned in the U.S. and Europe.

From the Bosnia War to South Africa’s struggle against apartheid, political posters have always played an important role in conflict and liberation movements. They have acted as a vehicle for mobilizing public opinion. In the Palestinian struggle, the poster has been an effective and important vehicle of expression. According to the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestinian Question’s entry on the Palestinian Poster, the years between the early 1960s to 1982 are considered “the golden age” of the Palestinian poster.

In the West Bank and Gaza, the Nakba was such a “radical rupture” that visual art and graphic production from Palestine all but disappeared, and a visual Palestinian identity only began to re-emerge in 1955, with silk-screening in Beirut. Political posters would experience a resurgence among the many political factions fighting during the Lebanese Civil War. Today the Palestine Poster Project has one of the most extensive archives of posters, from the early days of the struggle until the present day.

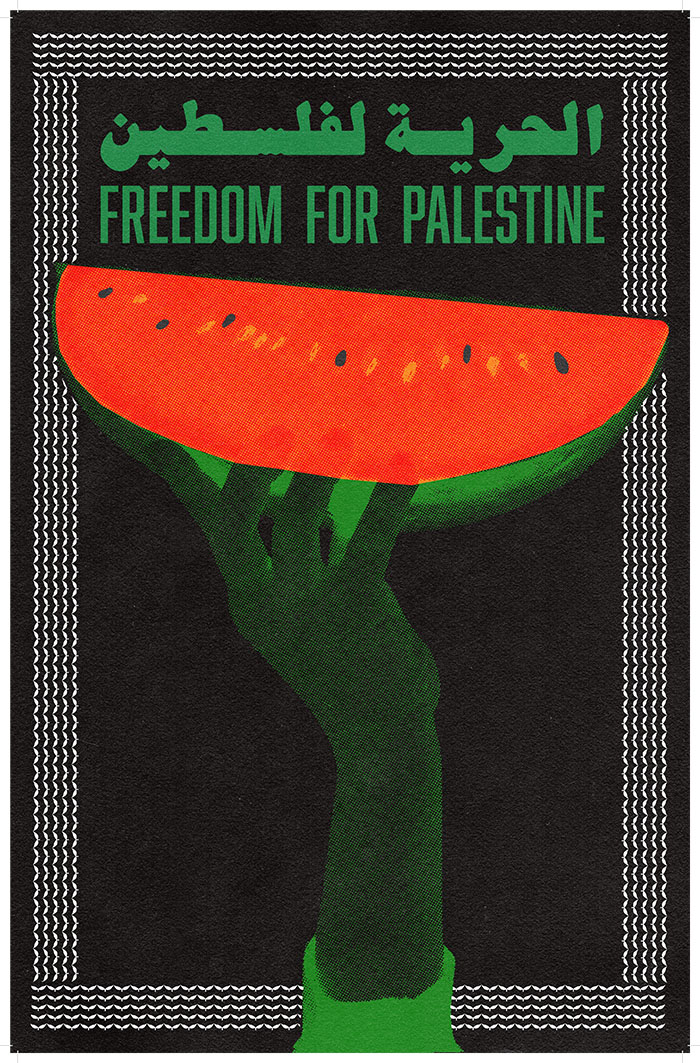

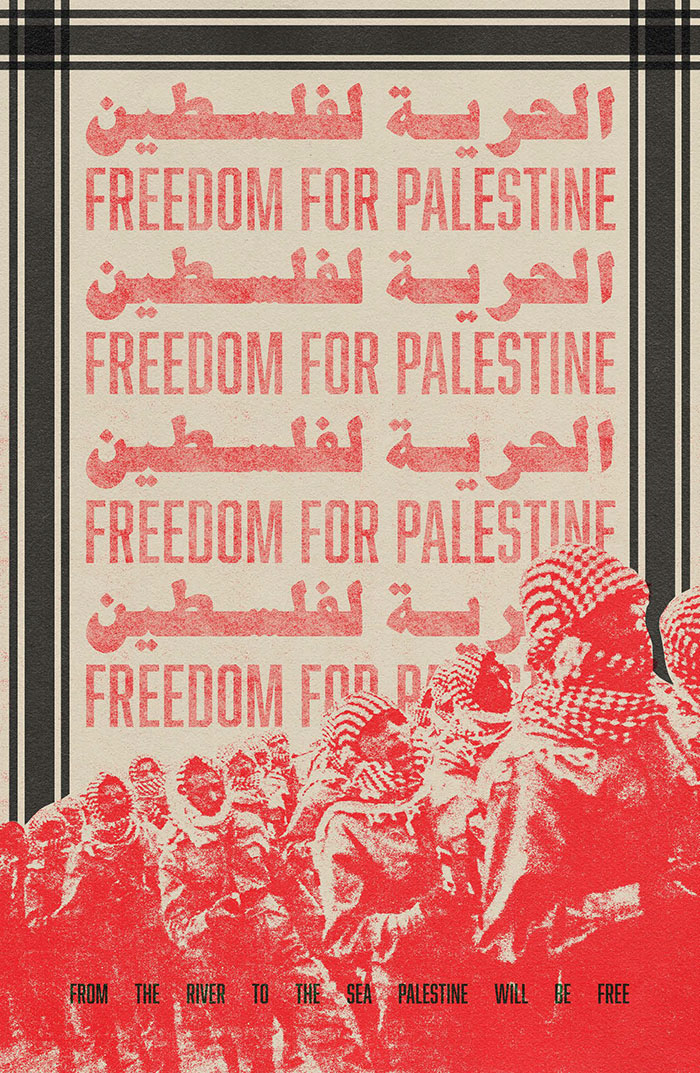

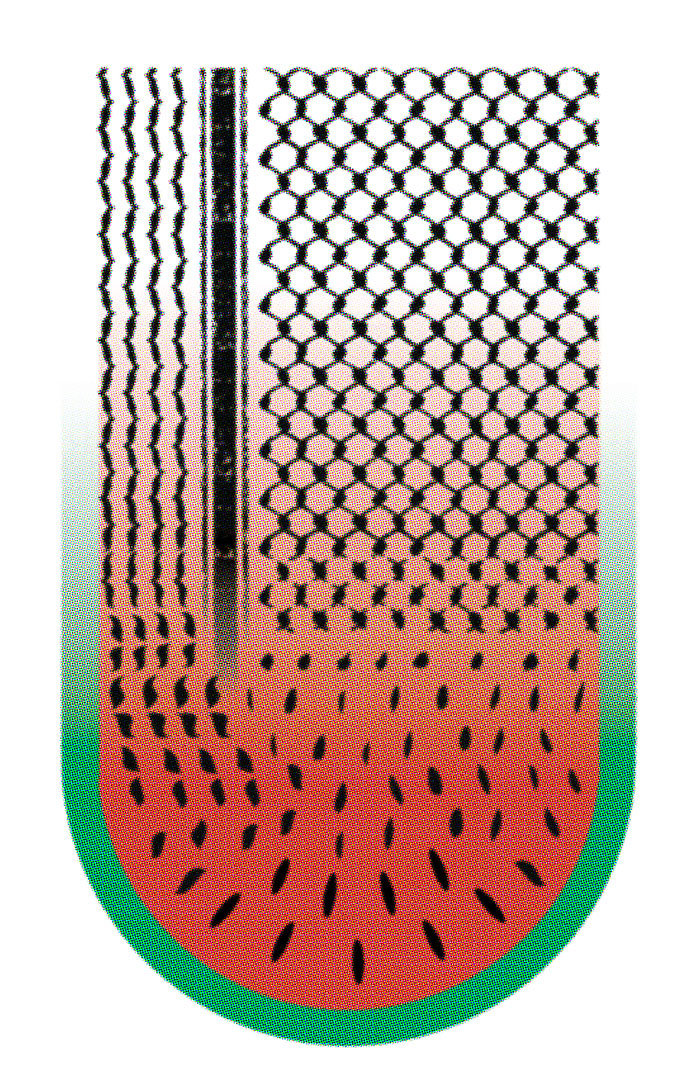

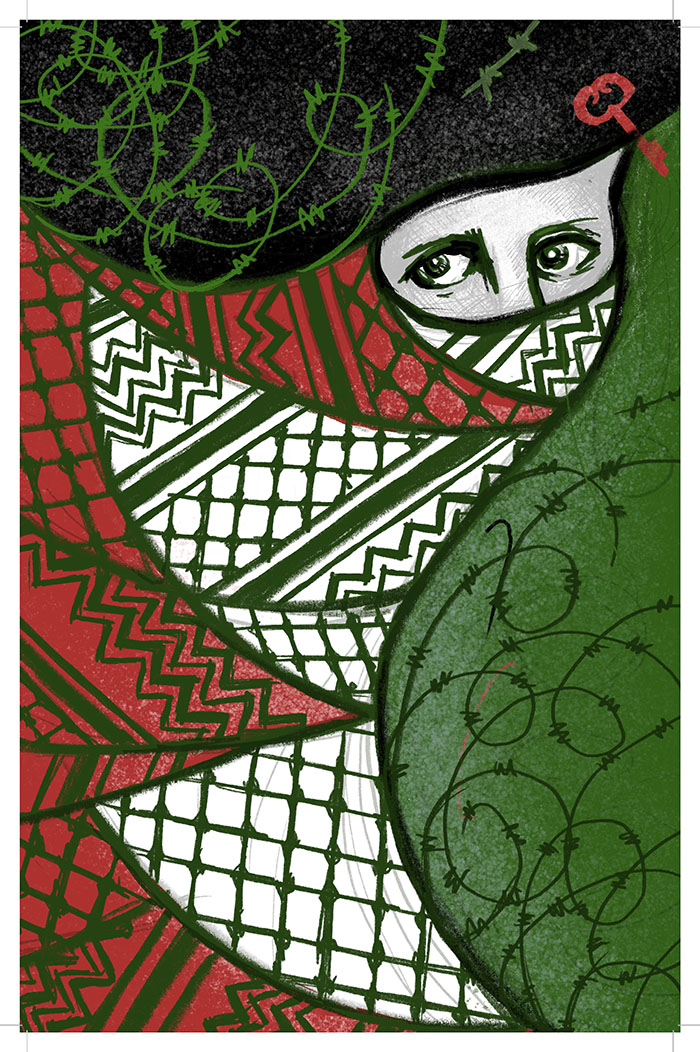

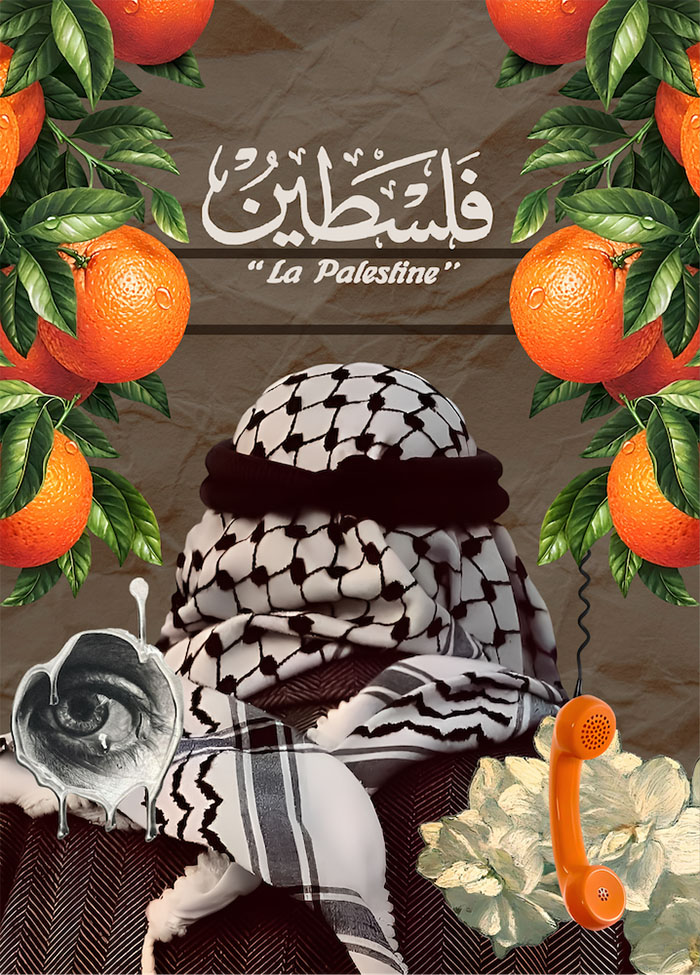

Art Against Apartheid is a poster initiative which collects and brings together hundreds of artworks and artists from around the world. The selected posters in Slideshow I incorporate different styles and color schemes, from Arabic calligraphy to the use of the watermelon, to bring a visual urgency to the call for freedom for Palestine. Artists also borrow elements from the Palestinian keffiyeh, from the country’s material and textile heritage, which has become a symbol of solidarity to the cause worldwide. Many posters, inspired by archival material, also make the connection between liberation struggles against colonialism, white supremacy and national borders.

Slideshow I features artists of varying ages, backgrounds and countries whose posters have been circulated among online campaigns and national protests; some of these posters have even been made into street signs.

“We Love Life,” which makes use of Arabic calligraphy, is by Lebanese art director and food stylist Rim Assal. She believes that artists play a major role in forging culture into an alluring entity, to prevent it from blending into imposed identity stereotypes that create an unbalanced and prejudiced world. Her Arabic lettering style is a detailed, mixed process of digitized hand-drawn sketches. Meanwhile, Abigail Buchwald’s “Watermelon Keffiyeh” interweaves Palestinian cultural symbols. In recent works, the watermelon has been heavily referred to as a symbolic representation of the Palestinian flag because of both the fruit and the flag’s black, white, red and green colors. The story of the melon’s transformation into a symbol of resistance dates back to the 1980s, when Palestinian artists Sliman Mansour, Nabil Anani and Issam Badr were arrested for painting and displaying the Palestinian flag at a time when the Israeli authorities had banned it in the Occupied Territories. Artist Victoria García also returns to the watermelon symbol in one of her posters. The other, “Palestine Will Be Free,” has been influenced by resistance symbology in archival photographs.

Among the artists from around the world expressing solidarity with Palestine is Tings Chak, from Beijing. Another is IMFKAMONI, a nonbinary artist of color, who sees art as a tool for liberation. They believe that all people under oppression are bound together in the same collective struggle fighting white supremacy. In their words, “Regardless of our location and identities, our freedom is intertwined and will only be gained when solidarity is actualized as a verb, globally.”

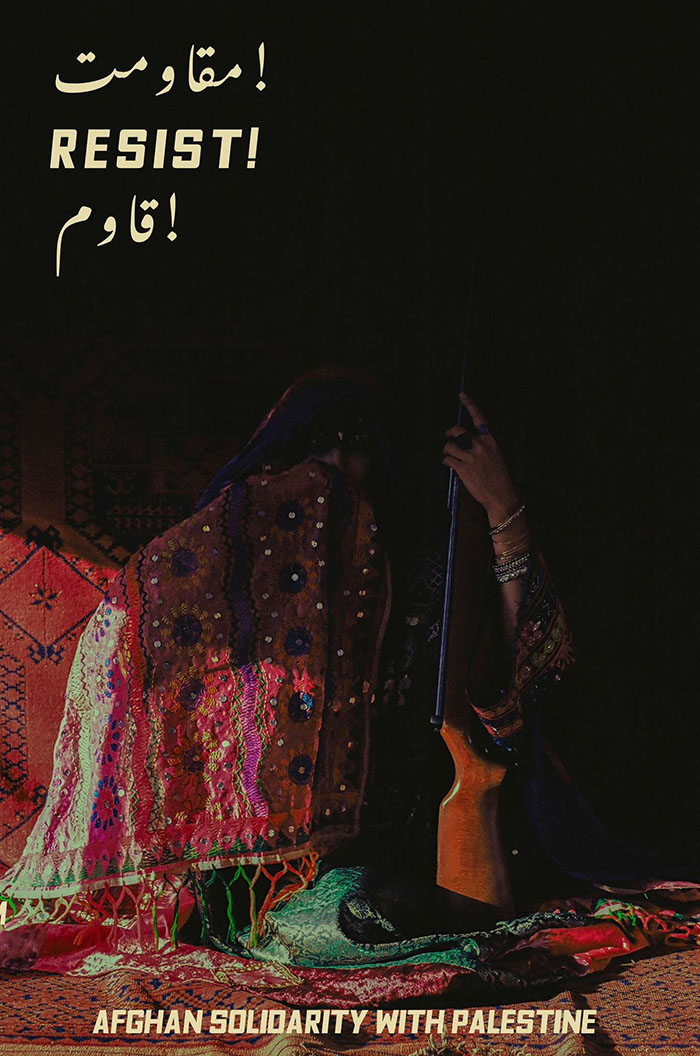

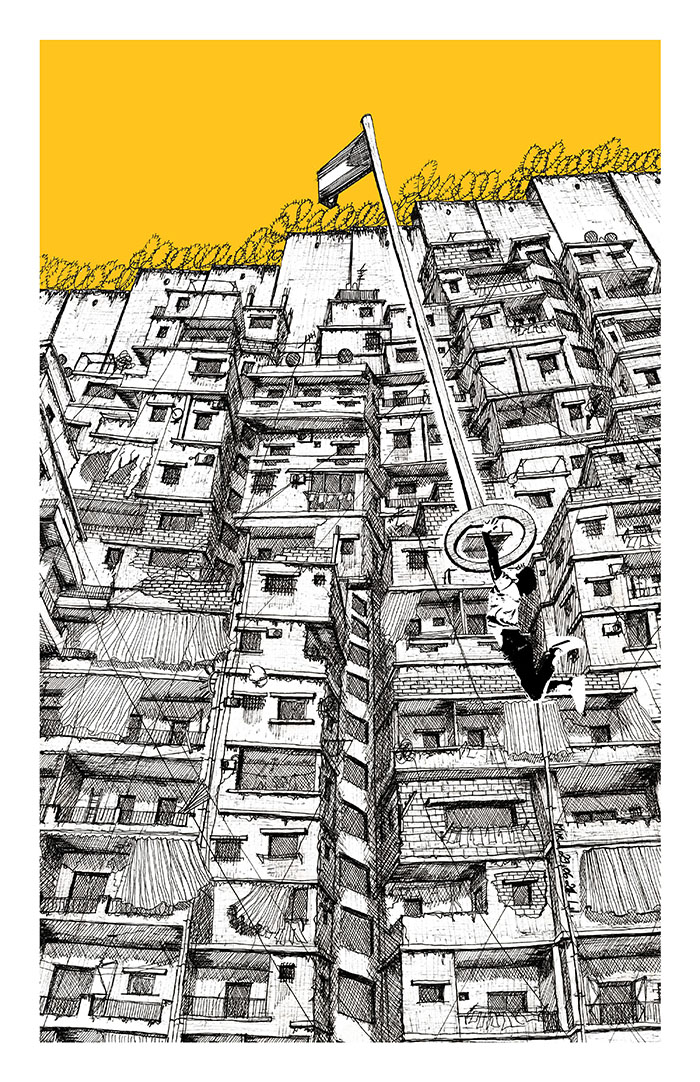

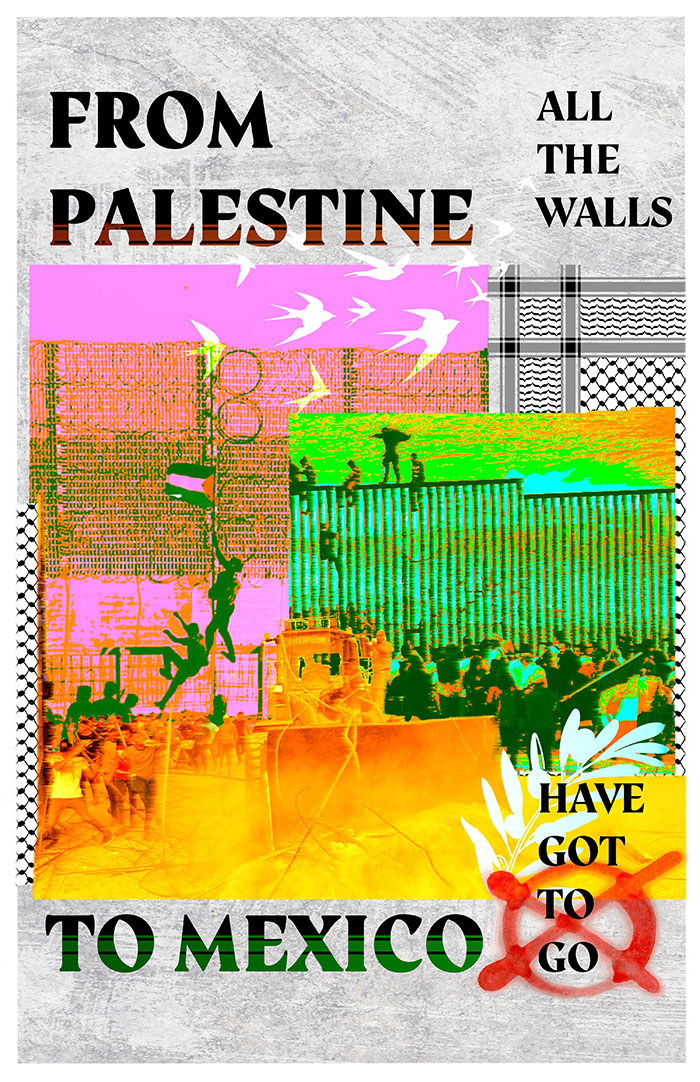

The poster by Kael Abello, a Venezuelan graphic artist and visual communicator based in Caracas, takes on the role of art in solidarity movements, as symbolized by a figure whose face is covered by a keffiyeh holding artists’ tools, alongside words in Spanish and English. Junaid Kator acknowledges the resistance of eastern people to global capitalism in “The Afghan Fighter,” a poster which depicts the role of revolutionary women who fought against the U.S. in the 1980s and again during the 2000–’22 American and allied forces’ occupation of Afghanistan. Architect and artist Lilia Benbelaïd returns to an iconic symbol, the key that many Palestinians kept from the homes from which they were expelled during the Nakba, and still have to this day, in the highrises of displacement in which they now find themselves. The poster by Tanya Núñez, Chicana (Mexican-American) filmmaker, human rights activist, and cultural worker is a reminder of the atrocities created by colonial and national borders in Palestine and Mexico.

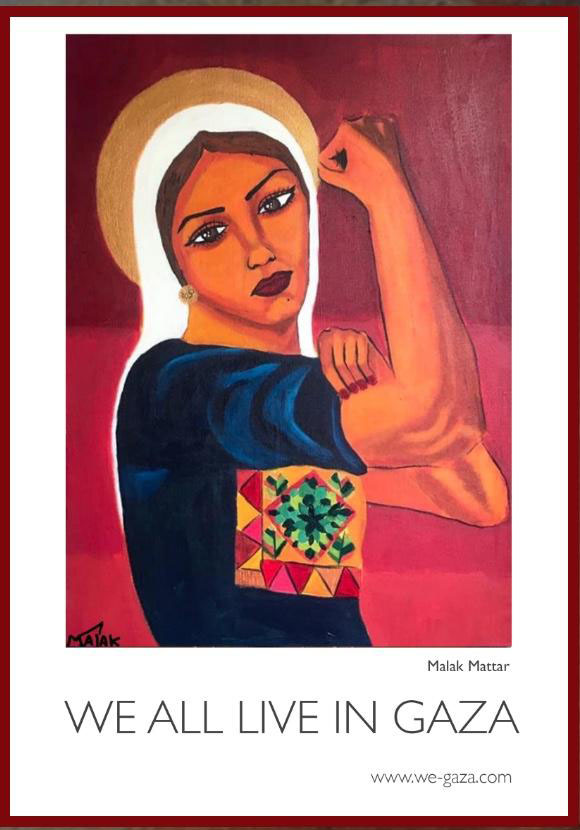

The work of Gazan artist, Malak Mattar, also appears on a poster on the website, We All Live in Gaza, an independent cross media project from the U.S. and UK, which chronicles conditions in Gaza not only from journalists, academics and policy makers’ viewpoints but more critically “from Gazans themselves living under siege.” The poster, based on Mattar’s 2019 self-portrait, reflects Gazan resilience.

Posters for Gaza

Until April 21, at Zawyeh Gallery Dubai, the group exhibition Posters for Gaza features the work of 26 Palestinian and Arab artists. The posters, created by established artists and a newer generation of artists, some of which have families on the Gaza Strip, aim to shed light on the ethnic cleansing and horrific massacres taking place there. In this imagery the artists are implicitly demanding an immediate cease-fire and recognition of the right to self-determination for Palestine.

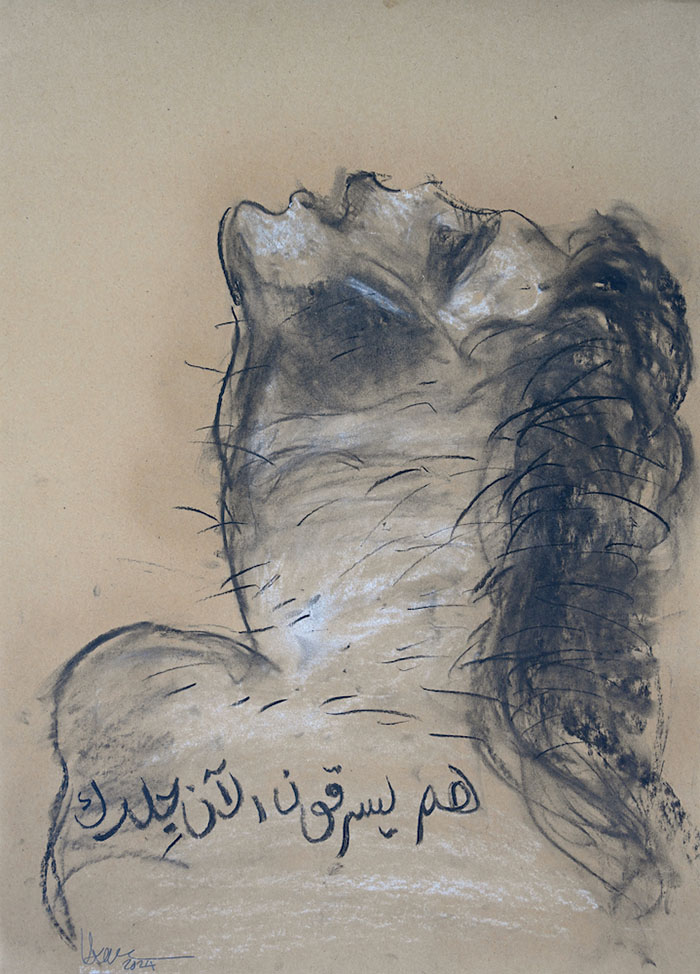

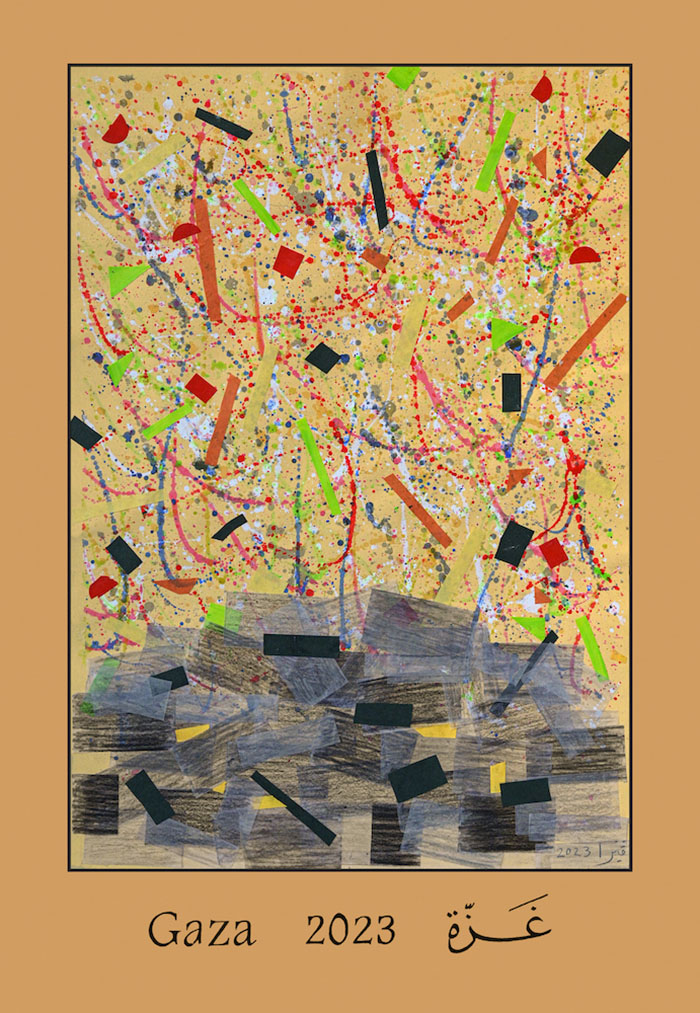

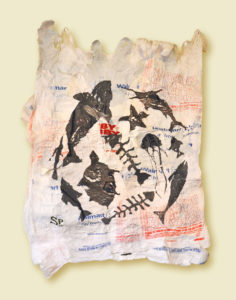

The artists use different methods whether traditional or digital. Gazan artist Hazem Harb returns to charcoal and paper to express the atrocities his people and family members experience. Harb’s father was recently detained by the Israeli army in Gaza and later released, suffering from critical health conditions due to mental and physical torture. In his artworks, Harb uses a variety of forms, from collage to archival material to mixed media to explore themes of landscape, colonialism, and memory, among others. Gaza-born Tayseer Barakat contributes with a poster reading “Children of Palestine Not Just a Number.” Barakat has had a prolific career in creating and teaching art with a preference in painting with many of his artworks inspired by the ancient influences of the region.

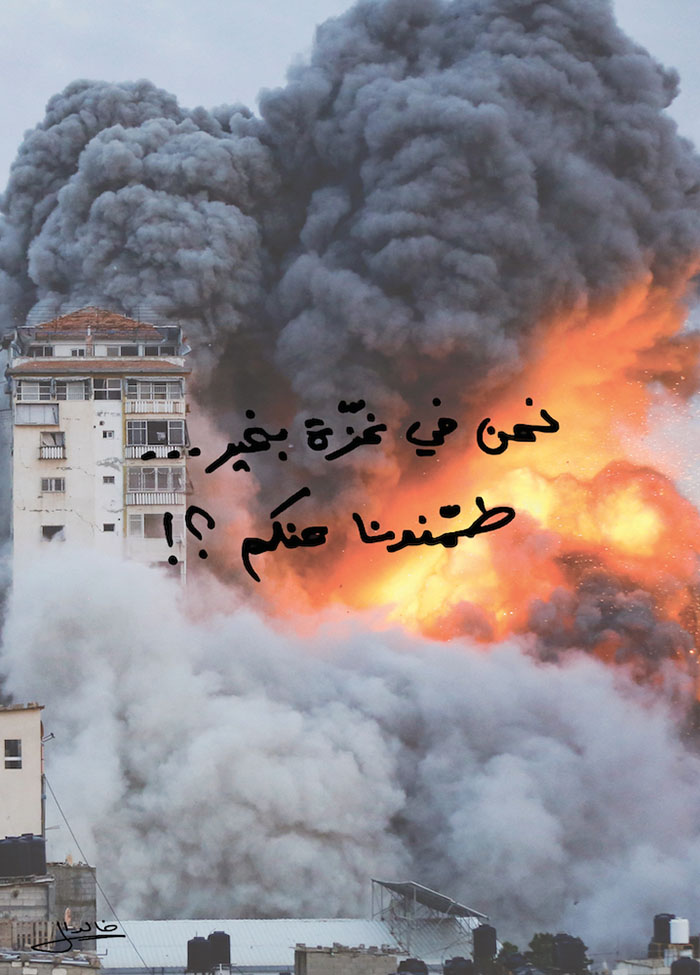

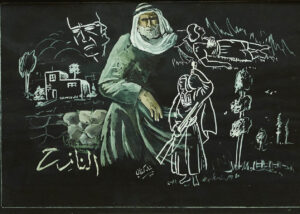

Many established artists in the exhibition Posters for Gaza use metaphor and draw from previous works for their posters, like Jerusalemite artist Rana Samara. Her artworks focus on women in crowded refugee camps, gender and sexuality issues, and women’s experiencing injustice by both conservative social traditions and living under Israeli occupation. Sliman Mansour, infamous for his artwork “Camel of Hardship,” centered land and the olive tree in his works, and has produced prolifically, having solo exhibitions in many cities worldwide including in Gaza. Vera Tamari, who contributed with “Gaza: From the Rubble Soars Life,” has experimented with clay and sculpture and what she calls sculpted paintings. Additionally, Nabil Anani, a key figure in Palestinian modern art, calls for a stop to the genocide in Gaza in his poster. Anani has also pushed for the use of local media and materials in art-making. Finally, Lebanese artist and singer, Khaled El Haber contributes to the Zawyeh poster exhibtion. El Haber is known for writing and producing songs for Palestine, including one on Gaza which has the same title as his poster, “We Are Doing Fine in Gaza … What about You?!”

A newer generation of Palestinian artists are also highlighted in Slideshow II with significant contributions using Arabic writing and calligraphy. Mahdi Baraghithi’s work appears with the Arabic words for liberty and freedom. Usually Baraghithi incorporates various media in his artworks such as collage, installation and performance, to deconstruct the image of the male body and masculinity in Arab societies. Haneen Nazzal’s poster “Against” also uses Arabic calligraphy, which translates into English: “After the burning of my land, my comrades, and my youth, how can my poems not become guns?” Nazzal’s work focuses on art’s role in liberation movements and indigenous identity.

Finally, artist Bashar Khalaf, contributes the poster, “God Make This House Safe,” the title of which appears in Arabic on the poster. Khalaf received several art awards by the Qattan Foundation, the Ismail Shammout Award, and the Palestinian Ministry of Culture. In 2019, he had his most recent solo exhibition at Zawyeh Gallery in Ramallah.

Dyala Moshtaha uses symbols of Palestinian heritage and the right to return in her poster. The oranges stand for Palestinian stolen land, while the old man wearing a keffiyeh or headscarf alludes to a generation who experienced the Nakba, but always longed for return, passing the struggle from one generation to another.

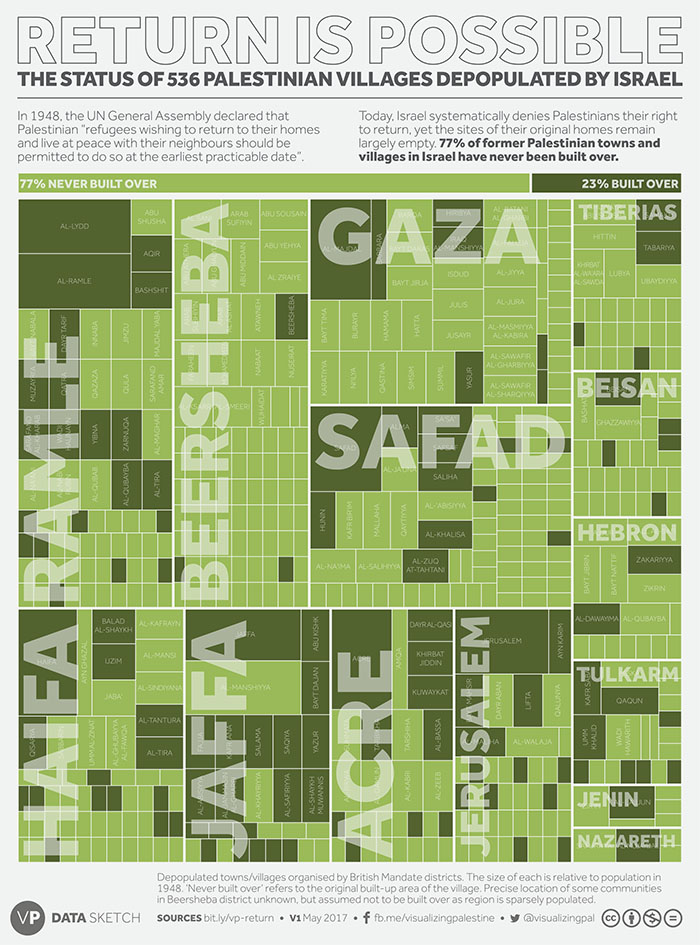

Still another kind of poster has been gaining popularity, one that eschews imagery for graphically, well presented information. On its website, Visualizing Palestine is described as “a small, multidisciplinary team that collaborates remotely from MENA to North America,” which “has honed the process of creating visual stories for social justice.” Its posters highlight genocide, torture and inhumane treatment of Palestinians, and the number of children in Gaza killed by Israeli forces, among a few of the topics in English — VP also produces posters in Arabic, Hebrew, French, Spanish, and other languages. The no-nonsense posters are stark and in your face in the best tradition of political protest art. However, some of their work, like the poster for “Return Is Possible: The Status of 536 Palestinian Villages Depopulated,” uses a plethora of information in an effectively visual way.

The wide variety of poster production by established Palestinian and Arab artists alongside emerging young Palestinian artists contributes to raising awareness of the Palestinian cause across the globe. The use of political posters in the past and the present, introducing mixed and digital media, keeps the space open for solidarity actions in different domains with arts as a strong tool for mobilization.

Proceeds from the online poster sale of Posters for Gaza from the Zawyeh Gallery Dubai will provide much-needed medical aid to affected children in Gaza, through the Palestine Red Crescent Society.

Hi, we are BDS Mexico and we print stickers with powerful messages to leave around Mexico City, we were wondering if we could use the one by Tanya Núñez “From Palestine to Mexico”, this phrase inspired a local artist Marianina and we would love to share both her account as well as yours and Tanya’s alongside with the sticker