During a period when Palestinians are being crushed by Israel's oppressive war machine, and heavy anti-Arab propaganda campaign, Basel Abbas & Ruanne Abou-Rahme remind us that Palestinians are still making art.

In one of the arch-vaulted rooms at Copenhagen’s Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, a number of gleaming reproductions of archaeological artifacts hang from the ceiling. Suspended in mid-air, the shiny black figurines seem engaged in a slow but almost ecstatic dance, casting shadows on the heliotrope-tinted footage of Palestinian landscapes adorning the walls. One of the reproductions, in particular, stands out. It’s that of a headless female, with slightly disproportionate, half-folded arms. She wears a necklace and a girdle, both depicted by straight grooves. The original idol is behind glass two rooms away, in another one of the galleries devoted to prehistoric art from the Middle East and Cyprus. We know very little about it other than the fact that it’s a female terracotta figurine from Syria dating back to the later part of the Bronze Age. It entered the museum’s collection only in 1987, an interesting date of accession, considering that an international convention was adopted as early as 1970 to prohibit and prevent the illicit import, export and transfer of cultural property.

Could it have been looted from Syria? How many times did it change hands? When did its journey of displacement begin? The idol — and its 3-D printed reproduction — resembles two of the anthropomorphic brown clay figurines unearthed almost a decade later, sometime between 1994 and 2010, at the archaeological site of Umm El-Marra in Syria, east of modern-day Aleppo. That excavation, led by Near Eastern archaeologist Glenn Schwartz, recovered more than two hundred clay figurines and fragments from the Bronze Age, showcasing the transition from hand-modeling to molding between the Middle and the Late Bronze Age. In 2011, the excavation was suspended indefinitely after the civil war made archaeological work in Syria impossible. The replica of the idol is one of the main characters in It is easy to forget what I came for among so many who have always lived here (2024), an installation by Palestinian duo Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme. Set in the Glyptotek, the work is part of a large exhibition comprising about 10 installations created by the duo over a number of years. Entitled The Song is the Call, and the Land is Calling, the entire show is a collaboration between the museum and Copenhagen Contemporary, a young art institution on the edges of the Danish capital.

A number of ancient idols and figurines from Anatolia and the Levant, drawn from the museum’s collection, were reproduced through 3D-printing for the exhibition, liberating them from traditional museography and situating them in new, porous narratives that extend far back into the past but also move forward into undefined tenses, into fluid contemporaneities. These assemblages of different elements, preserved from the past, resurrected in the present, mixed with leakages from the future, create a sense of parallel timelines and coexisting propensities. The idols on display at the museum show how paradoxical archaeological classifications are: Artifacts in the same classification can be separated often by thousands of years and have almost no continuity between them. Neolithic mother-goddesses, Kusura, Beycesultan, Troy or Caykenari-type idols, likely from Southwestern Anatolia, and early Iron Age terracottas from Syria, inhabit together that imaginary space called prehistory, only on the basis of certain vague typological features they share, in the same way that the Arab world or the Middle East is one continuous entity in the contemporary imagination.

In liberating, if not the fragile artifacts themselves, but at least their presence, from this rigid but unscientific taxonomy, releasing them into a vital, chaotic, throbbing performance that resembles a bacchic dance or a ritual gathering in the hinterland, Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s installation forces us to grapple with the gaps of our knowledge about them. Why do we call these enigmatic objects “idols” or “ritual objects” in the first place? Though they are quite common finds and have been crafted and used for millennia, we know very little about their origins, functions, or even who or what is being represented. The Glyptotek’s own file on the Troy-type idols tells us that they originate from residential houses where they served as house goddesses, votive gifts from temples. They have also been found interred with the dead, in graves situated in the Burdur region, near Antalya. And yet this object that accompanied families through life and death wasn’t simply a precious heirloom but also an everyday tool; perhaps a rattle, a talisman, an oracle and ultimately a burial offering.

Yet when we are immersed in the intoxicating sensorial experience of It is easy to forget what I came for among so many who have always lived here (the title of which is borrowed from a line in American poet Adrienne Rich’s anthology Diving into the Wreck (1973), and which the artists have frequently quoted in their works for the past decade), we might wonder what it is exactly that we are seeing and hearing. The multilayered sound samples, the rotating projections of Palestinian flora, and the intense pink-purple color that is the background of the entire exhibition bring up the question: How are Near Eastern archaeology, thistle flowers and dance performances connected with Palestine in the apocalyptic present, and what kind of representations of violence do they confront us with? The answer begins in the adjacent room, with the first part of the series And Yet My Mask Is Powerful (2016-2018), initially shown at the now defunct Alt Artspace in Istanbul, with the itinerant nonprofit Protocinema.

The video installation merges two different absorptions on the artists’ part. First, a fascinating youth movement that has emerged in Palestine, in which groups of young people take trips to visit the many Palestinian villages emptied and destroyed during the Nakba (there are over five hundred of them). These “visits,” which include summer camps and performances, are not nostalgic pilgrimages but rather reactivations, repossessions of these spaces and their meanings. In We Know What It Is For, We Who Have Used It (2018), the third part of their project And Yet My Mask is Powerful, the title once again borrowed from Rich, the artists write of these visits: “When they go out there it’s like the sites are not dead, they aren’t sites just of trauma, they are something much more. They are full of potential to imagine a time of their own making, S said, a time that is not set to a colonial calendar”. Indeed, in the videography, you can see young Palestinians entering these villages in the West Bank, on “time bending trips,” treading through the thick vegetation, searching for something, walking towards a somewhere, seemingly by instinct.

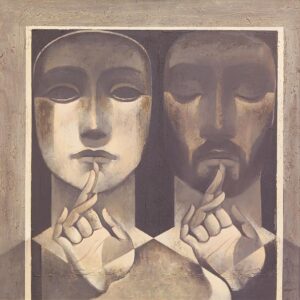

Superimposed upon this is the artists’ ongoing interest in the collection of antiquities “belonging” to Moshe Dayan, the army general and Israeli defense minister, who was also an infamous looter of antiquities. One of the objects in Dayan’s collection was a prehistoric mask looted from El Hadeb, near Hebron, known to the Israeli Antiquities Authority as the “Dayan Mask.” Dayan claimed that the mask was acquired from an antiquities dealer in Hebron, but rumors abound about it having been forcibly taken by Dayan and the Israeli army from the dealer or from a farmer who found it first. But this isn’t just any old mask. It belongs to a small group of artifacts, a series of 9,000 year old Neolithic masks, the oldest known in the world, that have been found throughout the West Bank and near the Dead Sea. All the sites in which the masks were found have ambiguous, pseudo-Biblical names bestowed upon them by the Israeli authorities, names such as “the Judean Desert” or “the Judean Hills;” attempts to obscure the extractive nature of the finds and the historical plunder, at the hands of the Israeli army, of cultural heritage in Palestine, turning all of it over to Israeli institutions and private collectors.

Dayan’s antiquities were sold to the Israeli state after his death, in a transaction that raised eyebrows among archaeologists. In 2014, the Israel Museum in Jerusalem displayed the entire group of masks, including the so-called Dayan Mask in an exhibition entitled Face to Face: The Oldest Masks in the World, which included an astonishing eight masks from a single private collection in the US. That private collector was hedge fund billionaire and ardent Israel supporter Michael Steinhardt, whose antiquities have often been at the center of legal controversy, with Italy, Greece, Lebanon and Turkey all having accused Steinhardt at different points of having knowingly acquired stolen or looted artifacts.

Abbas and Abou-Rahme weren’t able to attend the exhibition at the Israel Museum, but in And Yet My Mask Is Powerful (2016-2018), they set out to produce an intervention that would connect Palestinians, both physically and symbolically, not only to these destroyed villages, but with deep time: They decided to “hack” the masks. Using a virtual tour of the Israel Museum’s exhibition as their guide (made available by the museum itself), they replicated the masks with the help of a 3D designer and made multiple copies of them in different materials. Then, they took these replicas with them to the villages destroyed in 1948. Young Palestinians put them on to reenact rituals some ten millennia old. The performance with the masks wasn’t necessarily intended to reconnect past and present, but rather to enlarge time into what the artists have called “the space of projection,” an intermediate site between myth, fiction and wish. The original artifacts predate monotheism, and, as in the case of the Bronze Age idols, we know very little about their function — which is precisely why they operate as powerful symbols of human ambiguity.

The reproduction of the masks is a singular act of repatriation. One that questions the value and status of the original by returning the copy to an archaeological context that is traditionally regarded as destroyed or missing. Looking at the different stories of the theft and extraction of the masks — from Moshe Dayan, to a Polish priest, an English physician or Steinhardt’s collection — the artists propose an indigenous ontology: Removed from the landscape, the mask is dead, fossilized, and bereft of power. In We Know What It Is For, We Who Have Used It (2018), Abbas and Abou-Rahme write: “Its expression seemed sadder now that it had been deemed dead and placed under glass. It stayed there a long time, rarely seen and never touched. Until it returned here, in this new form we gave it. One could say that what’s there is the copy and what’s here is the real thing.” It’s an innovative way of thinking about heritage, combining prehistoric time with digital futures, and yet still not forgetting about the political meaning of archaeological and cultural plunder for displaced Palestinians.

The return to nature with the artifact is the crucial element here: While immersing themselves in the land, searching for the lost villages, the flora itself gave many clues about a pre-colonial time. Israeli settlers planted water-intensive, invasive European trees in the region, with the hope of erasing traces of Palestinian life, but certain natural markers such as the seasonal growth of shrubs, thistle and phacelia, reappeared in sites of destruction, providing a spatial orientation that defied colonial cartography. The intense heliotrope color of the shrub’s flowers, a purple-pink hue, became fundamental to many of the artists’ works since that period. In particular, the fluid, constantly changing and overlapping video-installations associated with their ongoing project May Amnesia Never Kiss Us in the Mouth (a large number of works from which is on show in the second part of the exhibition at Copenhagen Contemporary).

In contrast to that return to nature, the masks on display at the Israel Museum poignantly showcased the ongoing cultural and archaeological violence of the state. An Israeli newspaper reviewed the exhibition under the title “World’s Oldest Masks Come Home to Jerusalem”, resorting to the imperialist strategy of reading the entirety of the past, all the way to the most remote prehistory, as a part of the modern narrative of the nation state. And the process continues. As recently as 2018, a settler found another mask near Hebron, and it was promptly transferred to the Israel Museum. Last month, as Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s exhibition at the Glyptotek was still on, an amendment was proposed in the Knesset to the Israel Antiquities Authority law, to expand its jurisdiction to cover the entirety of the West Bank. Critics say it amounts to annexation under the guise of archaeology and antiquities, and could also stall much-needed infrastructure development, potentially forever. The government is taking advantage of the war against Gaza and Lebanon to further entrench lawlessness in the West Bank.

But the artists’ response to the colonial condition, which includes occupation, lawlessness, impunity and unrestrained violence, has never been one of simple mourning and despair. Many recent works from the series May Amnesia Never Kiss Us in the Mouth, both those present at Copenhagen Contemporary and the multi-room installation Until We Became Fire and Fire Became Us (2023), in the high-profile exhibition Nebula in Venice with Fondazione In Between Art Film, also still on view, emphasize the celebration of resistance. In a nonlinear poetic flow of prehistoric artifacts, traditional dances, indigenous plants and landscapes of displacement, the artists bear witness to the contemporary Palestinian experience during a time of genocide, but also resist the trap of becoming passive suffering subjects. They do not focus on the historical reconstruction of the facts of the occupation because it is an act that simply restates the condition of loss as irreversible, an incontestable imposition of colonial power. Their work is rather an attempt to open up a different space inside the present; a space that envisions other imaginaries, other possibilities.

They examine how communities experience violence and how they grieve, but also how they restructure themselves in moments of intense stress and suffering as a form of survival. The scattered, intoxicating, spinning narrative might seem disorienting at first, but it serves as a threshold to go beyond the present grief and to partake in the experience of what violence does to images, to bodies, to eyes, to memories. Abbas and Abou-Rahme have collected a vast archive of online videos of ordinary people singing and dancing in Yemen, Syria, Palestine and Iraq, and, working with musicians, they began writing performance scripts and overlaying, sampling, and resampling sounds to go along with them. The sound and live performance elements in their practice go back to the very beginning of their careers in the 2000s, when they discovered sound as a force that can travel through walls, defying the dead ends of the Israeli occupation that make movement through the West Bank and Jerusalem impossible for Palestinians. They have thus always been interested in interrogating conditions for which there is no current possibility of repair.

The most important gesture towards decolonization in their work, however, is not visual or historical but epistemic: The resistance to the ghettoization of the Palestinian condition as something unique and exceptional and unrelated to other conditions. But colonialism, as legal scholar Nasser Hussain argued in The Jurisprudence of Emergency, is not a historical period that ended, but a process and a world-system that can reappear at any time. The occupation of Palestine stands at an intersection between archaeology, jurisprudence, the utilitarian nature of humanitarian discourse, capitalist realism, warfare and imperialism. Abou-Rahme expanded on this in a conversation with curator Mike Sperlinger in 2023: “We use this condition to push back against the flatness of representation and images, and to open it to a multiplicity. To use this structure to think about the multiplicity of time and place that goes on at any given moment and refuse any singular narrative.”

And so It is easy to forget what I came for among so many who have always lived here (2024), tells us something crucial about modern archaeology, which is ultimately connected to the colonial present in Palestine and elsewhere. The Glyptotek’s collection of Anatolian and Levantine idols, displayed together in spite of the enormous temporal and geographical distance between them, as well as the gaps in our knowledge about them, is not a form of categorization unique that particular museum; similar displays can be found in many museums in Turkey, Greece, and the United States. But the artists’ installation reminds us that once upon a time, less than a century ago, these idols were not together at all. In fact, they were rarely exhibited; they lay in dusty boxes in museum storages and dig houses. Insofar as they didn’t explain anything about the worlds of Ancient Greece and Rome or the Bible, they were of little interest, and museum catalogs in the past even called them ugly monsters. It was only when modern art became interested in primitivism that idols became widely collected and classified into rigid categories.

Modern Western artists from the 20th century such as Picasso, Moore and Brancusi were all fascinated and inspired by these strange creatures from the remote past, which is what led, in part, to the formal creation of certain categories of prehistoric art, and in turn accelerated their plunder from the Eastern Mediterranean. But when Abbas and Abou-Rahme liberated them from their dormant state into a multitemporal, transitory state, placing them in conversation with destroyed villages, fragments of pottery, burnt wood and plants from the West Bank, the gleaming pink color of the flowers, poetry, songs, dances and sounds, perhaps they came back to life again, if only temporarily. Just like the masks, these mysterious objects of life and death began to serve not only as witnesses to destruction, but also as catalysts of rebirth, of cyclical return, of new life.

At the end of their parafictional text for the third part of And Yet My Mask Is Powerful, moving back and forth between wish and fact, desire and fiction, Abbas and Abou-Rahme offer us a powerful reflection. Standing on the traces of Palestinian villages, they have just completed a series of performances with the mask replicas and are no longer sure whether these are copies or not. “I looked out onto Kufer Birim through the strange circular eyes,” they write, “and all I could think was if this was meant as a spirit mask for the dead when it was made, what is a spirit mask for now? For the dead or for the living? I was surrounded by bushes, plants and trees that were all shades of phosphoric green. I don’t know if it was the effect of the heat or the mask but I felt like the whole place was alive, swarming with life. I just had to use the mask, to look out from under its eyes, to become it and let it become me. And then I could step out of time, out of the time they invented, this time that is occupied, this time they have declared me dead or dying. I am alive, this destroyed village is alive, this mask is for the living.”

We are thus left with a final impression that upends everything we think we know about archaeology. For when archaeologists began excavating in Greece, Anatolia and the Levant in the 19th century, they were certain that it was the past they were going to find. But instead, the artists show us, what in fact emerged was the present, flowing in all directions, contaminated, nebulous, untamable.

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)