The War Rugs exhibition at the British Museum belongs to tradition of war art in the 20th century. An art form with roots in the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan now features the modern weaponry of drones, Ukrainian flags, and the Taliban. It is the narration of war and political upheaval in the ancient craft of weaving

War rugs: Afghanistan’s Knotted History is on view at the British Museum in London until June 29 of this year.

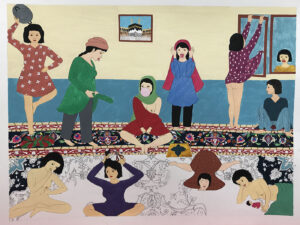

War rugs are aptly named, for both their content and context. Handwoven with motifs of guns, tanks, and military maps, they depict real military interventions into everyday life. These textiles are mainly produced by women of the Baluch (Baloch) and Turkoman (Turkmen) tribes, nomadic and semi-nomadic communities whose ancestral lands cross the borders of Iran, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

But even then, “we can’t say where these come from.” says Zeina Klink-Hoppe, curator of the British Museum’s exhibition, War Rugs: Afghanistan’s Knotted History, of — nominally — “Afghan” war rugs.

Although Kabul and Kunduz have been important centers for luxury textile production, the curator points to the textile central to the display: “The colors are Baluch, but the patterns are central Asian.” They recall the bold ikats now more often associated with Uzbekistan. Bukhara and Samarkand, the first capitol of the Timurid empire, were also key areas of carpet production. In many ways the War Rugs exhibition alludes to “shared traditions that cross the borders of space and time, entanglements revisited by a number of contemporary artists from the region and its diasporas,” including the Kuwaiti-Puerto Rican visual artist Alia Farid.

Expressions of Resistance

In “An Introduction to War Rugs,” the Jameel Curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum Rachel Dedman has written that, “A war rug may be an expression of resistance, a market-driven souvenir, and a reflection of political change.” She goes on to note, “Although motifs of military vehicles appeared in their weavings as early as the 1930s, war rugs as we know them today were mostly made from the 1970s onwards; the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan was one clear catalyst.” Primarily produced for personal use, in the home, they were soon made and sold to initially Soviet tourists — and later the Americans, with the arrival of US military forces following 9/11.

Klink-Hoppe, the British Museum’s curator of the modern Middle East, highlights how war rugs are also a “European product,” first mass produced in Hamburg, Germany, and patronized by collectors from Italy. Now rugs are exported from Peshawar, with dealers working across borders in the region. Textile historian and dealer John Gillow, from whom the Museum has purchased close to 700 objects, collected many in travels through Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The changes in consumer tastes and designs have been explored by the art historian Nigel Lendon, who describes these works as “the highest tradition of war art in the 20th century.” Yet, according to Dedman, there remains a lack of research undertaken from the perspective of the — predominantly women — weavers and makers, many of whom are forced to work in exploitative, factory-like conditions to meet market demand.

These shifts are visible in the textiles themselves in the War Rugs exhibition. Conflict and internal displacement encouraged the movement of weaving from the home, with the family, into workshops, and refugee camps in Iran and Pakistan.

A plurality of styles — from knotted rugs with tufted piles, to unknotted, flatweaves, and decorated goat skulls — are pulled out, to further reveal pluralities of patterns and motifs. There is movement from horizontal to vertical weaves, with larger working spaces, and the amalgamation of regional particularities, as women from different backgrounds mix and socialize.

Rugs often reference existing places, including the Blue Mosque at Mazar-e-Sharif, and everyday objects drawn from the home, such as teapots. Some of these rugs feature Cyrillic (Russian) languages, others, the word “Afghanistan” written in reverse, which Klink-Hoppe highlights as evidence of the illiteracy of many of their makers. By the final case, devoted to “Souvenirs and Western Demand” English appears more frequently.

Crucially, this is an exhibition that, as much as possible, communicates to the museum’s publics the perspectives and experiences of the object makers. The “native language” comes first in the captions. In the context of these perverse, parallel “booms” in the machinery of war and textile production, Klink-Hoppe is more concerned with the technology of the latter. The display features tools connected to carpet making, collected in the 1970s, as well as archive photographs, exposing the process of making. Though woven flat, the curators here hang the works for display — with industry-standard velcro. Another convention of Western/European institutional display — that unfortunately persists — is their trapping behind glass, denying publics the opportunity to see their backs.

Desire

War Rugs nevertheless enacts a subtle shift in focus, and gaze, from the fetishization of conflicts elsewhere. For curator Klink-Hoppe, a central concern was how to provide basic, accessible context — in an institution that restricts the length of labels to 100 words for introductions, and 60 words per object — about a region so diverse, yet often reduced to singular stereotypes of the “Middle East,” particularly concerning gender and religion.

The exhibition starts with a display on “desire,” not by or for women, but for natural resources, represented by inscribed seals, amulets, and cameos, made of minerals like lapis lazuli, garnet, and glass. These objects reflect Afghanistan’s own fragile, strategic position, a long held “prize in the 19th century “Great Game” for land and power.

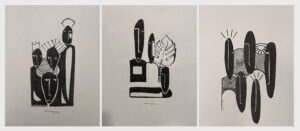

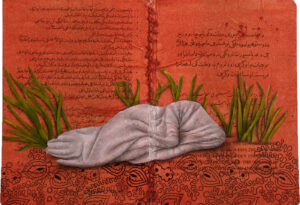

Lesser displayed miniature paintings likewise reflect shared cultural forms and, specifically, the significance of Buddhism in the region. Representations of the Buddhas of Bamyan in the 19th century are placed in conversation with contemporary responses by the artist Khadim Ali. He laments the recent destruction of cultural heritage by the Taliban, shared from his perspective as a Hazara, a mostly Shi’a Muslim ethnic group in a predominantly Sunni Afghan state.

Subtle nods to patronage and collections — often, women’s — likewise collapse the boundaries of time. From these early representations of “Bameean,” donated by Miss M. W. MacEwen in the 1970s, the exhibition moves to Timurid tiles bequeathed by Miss Edith Godman. They are the remains of grand public architectures, crafted and constructed by foreign hands, commissioned by chief consort Gawharshad and “her husband, emperor Shahrukh, in the 15th century.

More fragments from their mostly demolished Musalla, a multipurpose complex of academic and religious study, are respectfully nestled in a nearby case. (Gawharshad remains, though, best known for her eponymous, double-layered domed mosque at Mashhad in Iran, restored following Russian bombing in 1911, and the rebellion against Reza Shah in 1935.)

Symbolism

Some of the region’s reserves of gold, silver, copper, and rare metals — extracted and exported by the Mujahideen, to finance their resistance to Soviet occupation — might well have ended up in the same arms and weapons that proliferate in the region, and in these rugs. Poppies, a recurring floral motif, have a similarly destructive meaning. Woven into these textiles is thus the double destruction of the land — from below and above.

Revisiting specific places, as bedrocks beneath shifting political empires and dynasties, makes for more accessible history telling. Long before we as viewers encounter Herat’s kilim rugs, or its role as the late Timurid capital, the city is shown as a centre for metalworking in the Ghaznavid empire (977–1186), which stretched from Iran to northern India. A tinted drawing from the Safavid period, produced around 400 years later, also reflects its “refined” courtly culture, as one of many cosmopolitan centers of arts and learning in the Islamic world.

Much of this exhibition in Room 43A is not rugs. although, pride of place belongs to the “rug with vase and building” (1980–2000), flanked with angular camels, helicopters, and tanks. The weaving process makes for pixel-like forms, in which the human body incidentally becomes a tank, shaped by war. The rug also references the Shahnameh, or Book of Kings, with Soviet soldiers standing in for the horned White Divs.

Through a shared history between objects, British Museum curators in the Middle East Department cleverly extend their work. The case has space for just one scene from the Shahnameh, of Rustam killing the aforementioned White Divs. At the other end of Room 43A, many more are laid out for closer inspection. During my visit, the museum’s curator of the Islamic collections Shiva Mihan gravitates towards the last and largest, from the Great Mughal Shahnameh, which she describes as “the most beautiful ever.”

Early war rugs subtly incorporated motifs; in a “Garden carpet” (1980–1990), helicopters take the place of birds. Others feature the amaryllis, a readily available flower, as well as red tulips, the national flower of Afghanistan which also represents Nowruz, the new year’s celebration proscribed by the Taliban in the 1990s. Red variants of the former might be used to allude to the latter when their direct or explicit representation was banned, suggests Klink-Hoppe, “as watermelons do for the national colors of Palestine.”

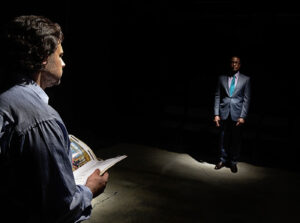

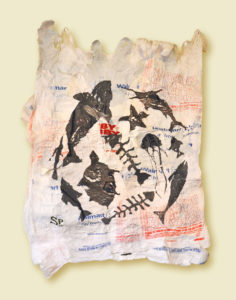

Over time, the presence of military technology becomes more explicit too, with more modern planes, yet the same AK47s, and tanks which recall Nintendo games consoles from the 1990s. These “cruder,” contemporary designs are now readily available online, the preserve of websites like warrugs.com, rugsofwar.wordpress.com — and the Imperial War Museum in London. There, Jim Ricks’ conceptual work “Predator (Carpet Bombing)” (2016), is laid in the center of the Blavatnik Art, Film and Photography Galleries.

Drawing from Amsterdam-based designer Ruben Pater’s Drone Survival Guide (2013), an illustration of various drone aircrafts, which itself references guides used to identify aircrafts in previous wars. While Ricks’ name is first credited, the rug itself was produced by the Kabul-based Haji Naseer and Sons Carpet Makers, where the drones on Pater’s survival guide are still in use. Placed in conversation with Walid Siti’s “War Series VI” (1987), the pair speak to continuities in present lives and lived experiences.

Part of a series of larger works, commissioned by curator Paul McAree for Telling Lies, a 2015 exhibition at Rua Red in Dublin, and later displayed at Creative Centenaries at the Ulster Museum in Northern Ireland, “Predator (Carpet Bombing)” included in the British Museum’s exhibition may also be considered another reflection of the relationship between Western/Europe, and Afghanistan — and across borders closer to home.

Curatorial Collaboration

Through the exhibition, the curators acknowledge the ambiguous agency of weaver women, often working to templates ordered by men, and also, at other times, realizing their creative expression. In this sense, these textiles embody the resistance — the push and pull — of both creative and curatorial practices.

War Rugs joins a line of thoughtful presentations all in Room 43A — including curator Venetia Porter’s 2022 display, Artists making books: poetry to politics, featuring Rokni Haerizadeh, Ramin Haerizadeh, and Hesam Rahmanian and Sadik Kwaish Alfraji, also shortlisted for the recent Jameel Prize 7; Nalini Malani; Issam Kourbaj; and Rachid Koraïchi, many of whom remain on view in the galleries today. Though closer in geography to the British Museum’s concurrent exhibition, ,Silk Roads, the War Rugs exhibition has more in common with Hew Locke: what have we here?, in illustrating how much can be unravelled in a comparatively small space — and how strategic, temporary displays can have more permanent legacies.

Tourism is especially well-represented, from romantic depictions of the natural landscapes, to later maps of the “Hippie Trail,” produced by the Afghan Ministry of Tourism. Klink-Hoppe explains how many of these early objects came into the British Museum’s collections through a single curator, with a particular interest in ephemera.

The chapan (cloak) of Hamid Karzai, Afghanistan’s interim leader and president between 2002 and 2014, was a diplomatic gift to the Museum following the 2011 exhibition, Afghanistan: Crossroads of the Ancient World. Deftly draped over a mannequin, its puppet-like installation receives a wry laugh from knowing publics, aware of his perception to many Afghans as a Western/European puppet — and, indeed, the reference to “Soviet puppet rugs” of Najbullah in the early 1990s.

These interventions ensure our perspective remains with the people. In the final case, the “coalition rug” of 2002 shows a large American flag, undermined by the inscription, “MADE IN PAKISTAN.” Yet beneath this grand narrative are a number of objects that stand testament to women’s often invisible labor at home, and weaving as a source of work and regular income — much like those shown in Rachel Dedman’s 2023 exhibition, Material Power: Palestinian Embroidery.

Where Dedman troubles with foreign investment and aid as a source of income, Klink-Hoppe emphasizes other complex relationships. Displacement and injury incurred through war has also led more men and children to start weaving, implying the inclusive potentials of the media. In contrast with Karzai’s chapan, miniature chadaris — brought back by soldiers as children’s dolls’ clothing or covers for alcohol bottles — here serve to tell the story of this clothing as a historic sign of respectability, rather than simply or only a symbol of repression.

Life-sized chadors can be seen at Hazara dress and embroidery from Afghanistan, a display at the nearby V&A, which also holds a substantial number of war rugs in its collection. Klink-Hoppe reveals the British Museum has already been offered another 30 such rugs since the opening of their display, though now, it is a case of “filling gaps” in the collection.

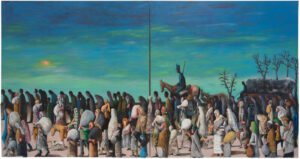

Each rug can take up to six months to produce. Still, they have experienced a swift induction into the canons of Western/European art history, with the first exhibitions in Italy, around 1985.The display closes with a more urgent focus, on the 1.4 million undocumented Afghan refugees expelled from Pakistan in 2023 — and many weavers returning to a life of danger under the Taliban government, and working on commission.

Their rugs shift too, from depictions of the Taliban and Twin Towers, to people clinging on to planes with the fall of Kabul (2021), and the flag of Ukraine, in solidarity with other struggles against Russia. Drone rugs have also become increasingly popular; Klink-Hoppe stresses how they are commissioned by ex-US military collectors from dealers in Peshawar — who continue to hold the copyright, another instrument of (economic) marginalization.

This plurality is well-represented in Klink-Hoppe’s fine display, which leaves out many threads to follow.