Ask any Palestinian where they were when the ‘Jaba bus accident’ happened, and they’ll probably recall it vividly. It remains ingrained in the Palestinian popular psyche, even with the West Bank having experienced its share of calamities before and since.

A Day in the life of Abed Salama, by Nathan Thrall

Allen Lane 2023

ISBN 9780241566725

Dalia Hatuqa

Ask any Palestinian where they were when the “Jaba bus accident” happened, and they’ll probably recall it vividly. It remains ingrained in the Palestinian popular psyche, even with the West Bank having experienced its share of calamities before and since. February 12, 2012 was a particularly gloomy day in the Holy Land. My husband, who worked for a UN agency at the time, had left for work early. The dark, ominous clouds made it particularly difficult for me to get out of bed. Awake but groggy, I was startled by a phone call. It was a number I didn’t recognize. I picked up the phone and a woman who introduced herself as one of my husband’s colleagues said that there had been an accident. She didn’t go into detail but told me enough to make me spring out of bed. What I made out of that quick conversation was that my partner would come back home well before the end of his workday.

I paced impatiently by the door until he arrived with a colleague. His blue eyes were bloodshot and bleary, a sight I had not encountered in all our years of marriage. We embraced and when his colleague left, he told me what had happened: On his way to Hebron, he and other UN staff had come across an accident site where a bus full of kindergartners had been hit head-on by a large truck. He and his colleagues leapt out to help, only to find some of the children already dead, their tiny bodies charred beyond recognition, and the truck driver screaming at his flattened legs. They loaded up their van with as many children as they could and drove them to the Ramallah hospital.

A Day in the Life of Abed Salama, which author Nathan Thrall expanded from his 2021 New York Review of Books essay of the same title, breaks down that devastating incident, in which seven Palestinians (six children and one adult) were killed. But it does a lot more than that. Starting with the emergency services reaching the scene of the accident too late — Palestinian ones were stuck at clogged arteries because of Israeli checkpoints, and Israeli first responders nearby arrived only after the children had been taken by good Samaritans to hospitals — Thrall peels back the systemic layers of inequality and injustice responsible for the victims’ fate. A reader who hasn’t encountered, much less lived through, Israel’s occupation might think that it was a series of unfortunate yet coincidental events that led to the children’s demise. But Thrall astutely paints a bigger picture that captures life in the West Bank, a place that’s isolated, suffocated, and subject to every facet of military rule imaginable. Fittingly, the book is subtitled “A Palestine Story.”

A reader who hasn’t encountered, much less lived through, Israel’s occupation might think that it was a series of unfortunate yet coincidental events that led to the children’s demise.

The author, who lives in Jerusalem, is the former director of the Arab-Israeli Project at the International Crisis Group, and authored an earlier book on Palestine-Israel titled The Only Language They Understand. He is well-equipped to tell this story. Thrall uses the life of Abed Salama, a Palestinian phone company worker and political activist, to expose the absurd and brutal reality of Palestinian life under Israeli rule. Salama’s son, Milad, was among the injured children whom bystanders gathered up and, in the absence of the yet-to-arrive emergency services, rushed to hospital. Salama spent the day looking for Milad before receiving the crushing news of his death. The little boy’s body was so badly burned that a DNA test was required to identify his remains. “Then Ibrahim called,” Thrall writes, referring to a relative of the Salamas. “He’d managed to get hold of the results through his connections. One of the children at the hospital morgue was Milad. […] Moments later the announcement came from the mosque’s loudspeaker: Milad Salama was dead.”

Thanks to Thrall’s deep dive into (Abed) Salama’s life — his first and forbidden love, his controversial work at Jewish settlements, and his unhappy marriage to his first wife — a nuanced picture emerges of a flawed man, one who reflects the broken political and military system he lives under. Salama’s family live in the narrow alleys of dilapidated Dahiyat al-Salam, in the enclave of Anata, next to Shuafat refugee camp. The camp is severed from East Jerusalem by the Israeli separation wall, which restricts access to hospitals and even determined where Milad would go to school. We learn that much of Anata, which was reduced from 12 square miles to less than one because of Israel’s repeated confiscation of its land, belonged to the Salamas. Despite being privately owned, the area was expropriated to make way for the nearby mushrooming Anatot settlement and an adjacent Israeli military base.

Throughout his book, Thrall doesn’t mince words. He writes openly, eloquently, clearly, and directly, providing a detailed account of life under colonization. The author includes the Nakba and even the very beginnings of Zionism within his scope. Crucial to understanding the fate of the schoolchildren in 2012 is what happened in the decades following the 1967 war, when Israel captured Palestinian-populated East Jerusalem from Jordan. Since then, the Jewish state’s vice-like grip around East Jerusalem’s neighborhoods has tightened. “Over the following decades, the demography and geography of the occupied territories was transformed by Israel, which used a range of policies to Judaize them,” writes Thrall, who uses Anata as a microcosm to illustrate the similar fate of other neighborhoods in Occupied East Jerusalem:

In Anata, the government seized the land piece by piece, issued hundreds of demolition orders, annexed part of the town to Jerusalem, erected a separation wall to encircle its urban center, and confiscated the rest to create four settlements, several settler outposts, a military base, and a segregated highway split down the middle by another wall, this one blocking the settlers’ sight of Palestinian traffic. The town’s natural pool and spring was turned into an Israeli nature reserve, which was free to the settlers of Anatot but charged admission to the people of Anata. The road to the spring went through the settlement, which Palestinians could not enter without a permit, so they had to use a different route, taking a long detour on a dangerous dirt road.

Although we discover that the bus hired to drive the children was old and not properly maintained, and that the driver of the truck which collided with it was careless, we also slowly come to understand the system of Israeli rule that led to the fatal crash. Palestinian neighborhoods are choked off by the West Bank separation wall and denied municipal services and infrastructural support, Israeli checkpoints delay or even prevent ambulances from making their way to Palestinian-populated areas, and bypass roads ensure that Israeli Jewish settlers travel independently of Palestinians, who are consigned to a network of neglected roads that lack lighting, police presence, and even dividers between two-way traffic. When put together, these pieces of the apartheid puzzle make it clear that the tragedy was avoidable and that its real roots — the wall, permits, IDs, shortage of Palestinian schools, lack of safe transportation — were never addressed.

Ultimately, A Day in the Life of Abed Salama grips you from start to finish. By the end, the reader is left angry, enervated, and pained. Thrall pulls off a very complicated feat by weaving much technical information on the crushing effect of Israel’s slow takeover of land, the maze of military checkpoints, and the bureaucracy that divides Palestinians from one another into a deft and engaging narrative. The book succeeds in laying bare the cruel reality of Palestinian life under Israeli military rule, which dictated the fate of those six children, while also paying homage to the humanity of its subjects.

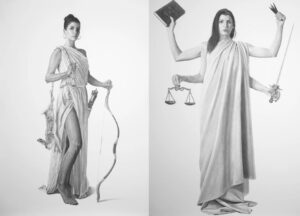

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)